Home » Evaluating and Treating Co-Occurring ADHD and Bipolar Disorder

Evaluating and Treating Co-Occurring ADHD and Bipolar Disorder

November 1, 2018

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Candace Good, MD

Child & adolescent psychiatrist, SunPointe Health, State College, PA, and a contributing writer for the Carlat newsletters.

Dr. Good has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity

Early into the evaluation of a 10-year-old boy, you note the following symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, sleep problems, racing thoughts, and moodiness. The boy’s parents came to your office convinced that their son has ADHD, but thinking through the case, you recognize that the same symptoms could signal bipolar disorder (BD). You have less than 45 minutes left; what’s your next step? How do you decide if this child really has ADHD, BD, or both?

This case example presents a common problem for child psychiatrists. We routinely see children with ADHD symptoms that don’t respond to treatment as usual. Numbers vary, with 0.5% of children with ADHD having BD and about 42% of those with BD having ADHD, according to recent studies (Arnold LE, Bipolar Disord 2011;13(5–6):509–521). Culture matters too; there is far more diagnostic overlap in the US than in the UK. In this article, we’ll discuss some tips to help you distinguish between the two conditions. We’ll also give you some commonsense advice on how to approach medication treatment in kids who present with symptoms of both ADHD and BD.

Interviewing and evaluation tips

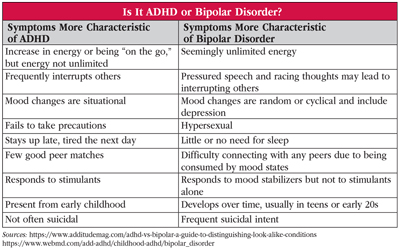

While there is some overlap between DSM-5 criteria for ADHD and BD, in general, ADHD is more a chronic problem of cognition and impulsivity, whereas BD is primarily an episodic mood disorder. Additionally, age of onset is typically younger for ADHD. (See the table “Is It ADHD or Bipolar Disorder?” below.)

How do we efficiently differentiate between these disorders? A detailed family history of BD, including who had symptoms and what worked and did not work in managing those symptoms, is helpful but not diagnostic per se.

Another piece of the picture is the clinical interview. I’ve noticed that children with mania may be disorganized in their thought process and behavior yet still appear well-groomed, because their caregivers are overseeing their activities of daily living. This may be true for parents of kids with ADHD as well. You can informally gauge the child’s level of function by considering how much the parents have to do to make up for the child’s deficits. Kids with ADHD are fast talkers and change topics quickly, but they can usually be interrupted—whereas those with mania will tend to talk over you. Kids with both ADHD and BD are daredevils and accident-prone, but manic patients may have unusual thoughts underlying the activity. For example, riding a bike too fast may be a symptom of impulsivity in ADHD, but it may be a quasi-psychotic, grandiose symptom in manic patients, who might be convinced they can fly. Other risky behaviors—such as sexting or viewing online porn—while sadly common in teens with ADHD, may signal frank hypersexuality in a manic child.

Families commonly interpret various “mood swings” as a sign of BD, but it’s important to carefully evaluate the kinds of mood variations that are taking place. Ask about the triggers or the duration of episodes. Children with ADHD may “crash” or “rebound” as their medication wears off in the afternoon, and they may “snap” when a limit is set. In BD, there may be no trigger for a mood shift that lasts hours or days. Regarding sleep, children with ADHD often function on less than the 9–11 hours typical of other school-aged kids. In mania, you will see episodic changes or greater severity of sleep disturbances.

Working with teachers

It’s rare for clinicians to talk directly with a teacher during a routine office assessment, but there are some standardized rating scales used in schools that can be helpful in diagnosis. For example, several studies have assessed the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL), which is often completed as part of the multidisciplinary evaluation process. If available, CBCL forms have ADHD-related scales and can also show a “deviant” profile indicating significantly increased risk for BD (Biederman J et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:732–740).

Additional testing

Research studies use detailed semi-structured interviews (K-SADS, WASH-U K-SADS) that aren’t practical in typical clinical practice. However, the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale (DBRS) can help you track severity of symptoms. Computerized continuous performance tests (CPTs) are not helpful in distinguishing between ADHD and BD, because both conditions cause restlessness and hyperactivity that drive errors of omission and commission. Newer computer tests, such as the Quotient ADHD system, include motion tracking that may provide additional data, such as scoring micro-movements as more consistent with ADHD. However, more research is needed on whether this approach can accurately differentiate ADHD from Bipolar Disorder I or II.

Pharmacologic treatment

When the diagnostic picture seems muddled in a new patient who is already on multiple medications, consider weaning the patient off existing medications to reestablish a baseline. This may require more frequent appointments or regular phone updates. Stopping meds, even if they don’t seem to be working, can be scary for families. Explain the risks of polypharmacy and document the discussion as well as the rationale for each medication.

You will sometimes have to make medication decisions even when the diagnosis is uncertain—typically, this happens when kids are doing poorly in school and there is pressure to quickly treat ADHD symptoms. If you suspect a mood component, use stimulants with caution, as they may disrupt sleep and trigger or exacerbate mood instability. Similarly, some non-stimulant ADHD medications, such as FDA-approved atomoxetine or off-label bupropion, could destabilize mood and worsen mania. Rather than starting with stimulants, consider ADHD meds that are less likely to cause mood instability, such as centrally acting alpha-2 agonists (clonidine, guanfacine).

When a mood disorder is part of the diagnostic picture, give it treatment priority over other conditions. For Bipolar I or II, it is preferable to start with an agent that has FDA approval for treatment in this age group. Several second-generation antipsychotics are FDA-approved for adolescents (starting ages vary): aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine (Bipolar I), and lurasidone, as well as lithium (ages 12–17). If ADHD symptoms persist, it’s OK to add a stimulant. In the 8-year follow-up to the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), rates of mania remained low, suggesting that stimulants themselves don’t trigger mania (Molin B et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:484–500). Other trials support the safety and utility of adding stimulants in populations already treated with a mood stabilizer (Scheffer RE et al, Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:58–64; Findling RL et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46(11):1445–1453). Some side effects of stimulants, like appetite suppression, can actually be favorable for youths with BD, as they may limit the weight gain typically seen with mood stabilizers like divalproex sodium, lithium, or antipsychotics.

CCPR Verdict: Dig a little deeper to differentiate ADHD from bipolar and other mood disorders, as a significant number of patients meet criteria for both. Prioritize treating the mood disorder and proceed carefully from there.

Child PsychiatryThis case example presents a common problem for child psychiatrists. We routinely see children with ADHD symptoms that don’t respond to treatment as usual. Numbers vary, with 0.5% of children with ADHD having BD and about 42% of those with BD having ADHD, according to recent studies (Arnold LE, Bipolar Disord 2011;13(5–6):509–521). Culture matters too; there is far more diagnostic overlap in the US than in the UK. In this article, we’ll discuss some tips to help you distinguish between the two conditions. We’ll also give you some commonsense advice on how to approach medication treatment in kids who present with symptoms of both ADHD and BD.

Interviewing and evaluation tips

While there is some overlap between DSM-5 criteria for ADHD and BD, in general, ADHD is more a chronic problem of cognition and impulsivity, whereas BD is primarily an episodic mood disorder. Additionally, age of onset is typically younger for ADHD. (See the table “Is It ADHD or Bipolar Disorder?” below.)

Table: Is It ADHD or Bipolar Disorder?

(Click to view full size PDF.)

How do we efficiently differentiate between these disorders? A detailed family history of BD, including who had symptoms and what worked and did not work in managing those symptoms, is helpful but not diagnostic per se.

Another piece of the picture is the clinical interview. I’ve noticed that children with mania may be disorganized in their thought process and behavior yet still appear well-groomed, because their caregivers are overseeing their activities of daily living. This may be true for parents of kids with ADHD as well. You can informally gauge the child’s level of function by considering how much the parents have to do to make up for the child’s deficits. Kids with ADHD are fast talkers and change topics quickly, but they can usually be interrupted—whereas those with mania will tend to talk over you. Kids with both ADHD and BD are daredevils and accident-prone, but manic patients may have unusual thoughts underlying the activity. For example, riding a bike too fast may be a symptom of impulsivity in ADHD, but it may be a quasi-psychotic, grandiose symptom in manic patients, who might be convinced they can fly. Other risky behaviors—such as sexting or viewing online porn—while sadly common in teens with ADHD, may signal frank hypersexuality in a manic child.

Families commonly interpret various “mood swings” as a sign of BD, but it’s important to carefully evaluate the kinds of mood variations that are taking place. Ask about the triggers or the duration of episodes. Children with ADHD may “crash” or “rebound” as their medication wears off in the afternoon, and they may “snap” when a limit is set. In BD, there may be no trigger for a mood shift that lasts hours or days. Regarding sleep, children with ADHD often function on less than the 9–11 hours typical of other school-aged kids. In mania, you will see episodic changes or greater severity of sleep disturbances.

Working with teachers

It’s rare for clinicians to talk directly with a teacher during a routine office assessment, but there are some standardized rating scales used in schools that can be helpful in diagnosis. For example, several studies have assessed the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL), which is often completed as part of the multidisciplinary evaluation process. If available, CBCL forms have ADHD-related scales and can also show a “deviant” profile indicating significantly increased risk for BD (Biederman J et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:732–740).

Additional testing

Research studies use detailed semi-structured interviews (K-SADS, WASH-U K-SADS) that aren’t practical in typical clinical practice. However, the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale (DBRS) can help you track severity of symptoms. Computerized continuous performance tests (CPTs) are not helpful in distinguishing between ADHD and BD, because both conditions cause restlessness and hyperactivity that drive errors of omission and commission. Newer computer tests, such as the Quotient ADHD system, include motion tracking that may provide additional data, such as scoring micro-movements as more consistent with ADHD. However, more research is needed on whether this approach can accurately differentiate ADHD from Bipolar Disorder I or II.

Pharmacologic treatment

When the diagnostic picture seems muddled in a new patient who is already on multiple medications, consider weaning the patient off existing medications to reestablish a baseline. This may require more frequent appointments or regular phone updates. Stopping meds, even if they don’t seem to be working, can be scary for families. Explain the risks of polypharmacy and document the discussion as well as the rationale for each medication.

You will sometimes have to make medication decisions even when the diagnosis is uncertain—typically, this happens when kids are doing poorly in school and there is pressure to quickly treat ADHD symptoms. If you suspect a mood component, use stimulants with caution, as they may disrupt sleep and trigger or exacerbate mood instability. Similarly, some non-stimulant ADHD medications, such as FDA-approved atomoxetine or off-label bupropion, could destabilize mood and worsen mania. Rather than starting with stimulants, consider ADHD meds that are less likely to cause mood instability, such as centrally acting alpha-2 agonists (clonidine, guanfacine).

When a mood disorder is part of the diagnostic picture, give it treatment priority over other conditions. For Bipolar I or II, it is preferable to start with an agent that has FDA approval for treatment in this age group. Several second-generation antipsychotics are FDA-approved for adolescents (starting ages vary): aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine (Bipolar I), and lurasidone, as well as lithium (ages 12–17). If ADHD symptoms persist, it’s OK to add a stimulant. In the 8-year follow-up to the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), rates of mania remained low, suggesting that stimulants themselves don’t trigger mania (Molin B et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:484–500). Other trials support the safety and utility of adding stimulants in populations already treated with a mood stabilizer (Scheffer RE et al, Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:58–64; Findling RL et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46(11):1445–1453). Some side effects of stimulants, like appetite suppression, can actually be favorable for youths with BD, as they may limit the weight gain typically seen with mood stabilizers like divalproex sodium, lithium, or antipsychotics.

CCPR Verdict: Dig a little deeper to differentiate ADHD from bipolar and other mood disorders, as a significant number of patients meet criteria for both. Prioritize treating the mood disorder and proceed carefully from there.

Issue Date: November 1, 2018

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)