Published On: 11/7/22

Duration: 19 minutes, 30 seconds

Today, the fifth psychopharm commandment: Don’t mix benzos with opioids in high-risk patients.

Chris Aiken: Welcome to the Carlat Psychiatry Podcast, keeping psychiatry honest since 2003. I’m Chris Aiken, the editor in chief of the Carlat Report.

Kellie Newsome: And I’m Kellie Newsome, a psychiatric NP and a dedicated reader of every issue.

Chris Aiken: Industrial medicine is relatively new. It wasn’t until the 1827 that high potency, mass-produced meds were widely available. Before that, the pharmacologist was an herbalist, grinding up extracts to treat all kinds of ailments. And with this mass production came high profits, high research budgets, and new cures that we cannot take for granted, like antibiotics and antipsychotics. But there was a drawback to all this excess: Addiction substance use disorders and overdose deaths.

The two are related, but they are not the same. Addiction is when industrial production amplifies the rewarding effects of a medication, either by increasing its potency or boosting its speed of onset. Cocaine didn’t cause much trouble for the indigenous people of South America who chewed on the cocoa plant for centuries to lift their energy and mood. But purified, high potency, intranasal cocaine is a different beast. Likewise with tobacco – it was never healthy – but it did not cause the kind of addiction and health problems until RJ Reynolds figured out how to mass produce the potent, quick fix of the packaged cigarette, a delivery system that allowed people to inhale more nicotine per hour than ever before.

KELLIE NEWSOME: Industrial opioids entered the scene with heroin, made by Bayer, the same company that brought us aspirin. Heroin replaced the less potent opium, and it did so at an opportune time, as America was recovering from the civil war and hundreds of thousands of wounded veterans were suffering chronic pain. The drug proved useful, but it also proved deadly, and by 1900 there was an opioid epidemic in America. People were using opioids not just for pain, but for all that ails: Insomnia, depression, anxiety, GI distress, etc. Soon, industrial medicine developed an unlikely replacement to come to the rescue: Barbiturates.

CHRIS AIKEN: Barbiturates were welcomed as a safer alternative to opioids, particularly for people with psychiatric complaints. And at first, they were, but production revved up after WWII, and it was at that time – 1945 – that the death rate started to climb. You may be familiar with the prominent lives that were lost to barbiturates during that epidemic – Marilyn Monroe, Bruce Lee – but for every celebrity there were many more among the uncelebrated. XXX died by barbiturate OD. Most of these deaths did not involve suicide or addiction. People simply took a little too much of the barbiturate, to calm their nerves and sleep, or combined it with alcohol – and they stopped breathing.

KELLIE NEWSOME: Barbiturate overdoses peaked in 1960, and here’s why. It was in that year that the pharmaceutical industry released yet another solution: Chlordiazepoxide (Librium), the first benzodiazepine, followed a few years later by its metabolite diazepam (Valium). Benzos were less potent than barbiturates when it came to anxiety and insomnia, but they had a considerable advantage: It was very hard to overdose on them. If you took too many, it would knock you out and you’d likely wake up after a long sleep. But it wouldn’t stop your breathing. Actual deaths from benzodiazepine overdose were – and remain – very rare. What has changed, and brought us to the third epidemic, is a new medication with much more perilous effects: the Benzo-Opioid combo.

CHRIS AIKEN: To be fair, no one has ever marketed a benzo-opioid combo pill, and I don’t know of any physicians who endorsed this unwise combo. It’s rise was inadvertent, and began in the 1990’s when the pharmaceutical industry partnered with optimistic physicians who believed that medicine was ignoring an epidemic of pain, either because they were afraid of getting their patients addicted to opioids or they just thought a stiff upper lip was the best approach.

Opioids, it turns out, are addictive – about 8-26% people who are prescribed opioids for pain develop addictive behaviors around them that range from drug misuse to an opioid use disorder. They are also not very effective for chronic pain, and cause tolerance in many patients, leading to higher and higher doses. And as the dose goes up, so does the risk of accidental overdose, because opioids can bring respiration to a stop.

KELLIE NEWSOME: This is where benzodiazepines come in. They don’t suppress breathing enough to cause death on their own, but when combined with opioids or other respiratory suppressants like alcohol they can. Benzodiazepines are involved in a little over half of opioid fatalities, and when you prescribe a benzodiazepine to a patient on an opioid it raises their risk of overdose death 2 to 4 fold. No one anticipated how big this problem would be, but whether it’s because of muscle spasms or psychiatric symptoms a lot of patients who were placed on opioids were also taking a benzodiazepine.

CHRIS AIKEN: And if they weren’t, they might start seeking them, because benzodiazepines enhance the opioid high. There is a cross-addiction between benzos and opioids that is just as powerful as the more well-known cross addiction that happens between benzos and alcohol. For example, if you prescribe a benzo to a person who is in recovery from an opioid use disorder, it makes them more likely to relapse into opioid use, even if they never misuse the benzo.

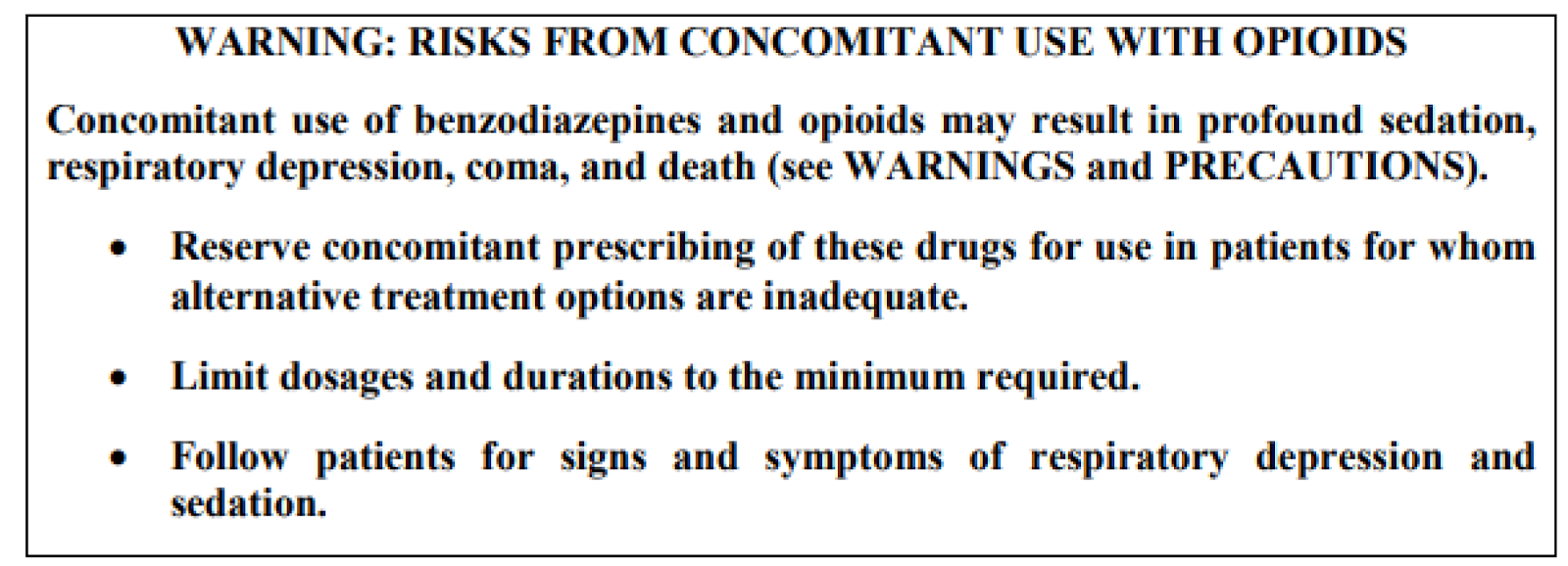

KELLIE NEWSOME: Anna Nicole Smith. Amy Winehouse. Heath Ledger. Michael Jackson. Whitney Houston. Thomas Kinkade. Phillip Seymour Hoffman. Prince. Tom Petty. That’s an abbreviated list of celebreties who died of drug overdose between 2007 and 2017. And although most of those deaths involved opioids (and, in the case of Michael Jackson, propofol), in each case there was another familiar medication onboard: a benzodiazepine. As awareness of the benzo-opioid risks grew, the FDA placed a warning on benzodiazepines in 2016. Let’s read that:

CHRIS AIKEN: The FDA’s advice is well-intended, but not very useful, because they are telling us to do what we’ve been doing all along – try other options first and minimize the dose and duration of benzodiazepines. These tax-funded tips don’t tell us what we need to know: Where do we draw the line? When is it reasonable to continue the benzodiazepine, and when do we need to stop it? So we went on a deep dive to figure that out, and you’ll find that on a chart in the Carlat Report. If you subscribe to the journal, it’s in the September 2018 issue, in an article called New Risks with an Old Drug. Or if you have our textbook Prescribing Psychotropics, you’ll find it on page 136.

KELLIE NEWSOME: We’ll summarize and update that article for you here. We divide patients into three risk categories – red light, where you need to hold the benzo; yellow light, where the risks are high and you better do all you can to minimize them and justify the use; and a flickering green light – flickering because benzos and opioids are never really safe together, but we can at least carve out a group where the risk is low.

The red light is pretty clear. Don’t use benzo with opiods in patients with….

- Active prescription misuse

- Active addiction to benzos, opioids, alcohol, or other sedatives

- History of sedative overdose

- Methadone use or on maintenance therapy for opioid use disorder

That last one deserves some comment. Methadone in particular has a high rate of overdose death, probably because of the drugs long half-life. It tends to linger around, giving more opportunities for accidents. For patients in MAT maintenance opioid therapy, we just recommend you defer to the MAT program. Some MAT programs might prescribe the two together because they believe the risk of death will be higher if they turn those patients away and they die on the streets. But that’s a tough call to make, and after the call is made it requires careful follow up that is best provided by the MAT program itself.

CHRIS AIKEN: Next come the yellow lights. These are patients who have psychiatric or medical problems that increase their risk of overdose, or who are taking high doses of opioids. By high doses we mean greater than or equal to 50 morphine milligram equivalents. Your state’s controlled substance monitoring program might give you that number, or you can calculate it online, just google Oregon opioid calculator.

Psychiatric problsm that raise caution include:

History of sedative, alcohol, or opioid use disorder

Borderline or antisocial personality disorder

Unstable psychiatric disorder

Medical disorders:

Respiratory disease (eg, COPD, sleep apnea), systemic medical illness (eg, HIV, organ failure, renal or hepatic impairment), or pregnancy

• Age ≥ 65

KELLIE NEWSOME: The last level is the shaky green light – that’s anyone who doesn’t have the problems above. So if your patient is a young adult who is psychiatrically and medically stable, has not history of substance use disorders, and is on a low dose of a short-acting opioid that they take as needed for shoulder pain, the opioid-benzo combination is not ideal but it is much safer.

[Music Transition]

CHRIS AIKEN: With the red light you stop. With the green light, you can keep going. But what do you do with the yellow light? We’re not comfortable just following the FDA’s advice and continuing the benzo if it’s medically necessary and other options have failed – that’s good advice for the green light, but the risk of death is high.

KELLIE NEWSOME: The lifetime mortality rates tell it best. The chance of a person dying in their lifetime is 100%, but there are thousands of things that might kill you. The lifetime mortality rate breaks that down. In 2020, the most common causes of death were heart disease – 1 in 6 deaths – and cancer – 1 in 7. COVID-19 was 1 in 12. Suicide: 1 in 93, Car accident: 1 in 101. But opioid overdose is more likely than suicide or car accidents at 1 in 67, and despite all the warnings that rate is not going down – it was 1 in 93 just 3 years earlier in 2017.

CHRIS AIKEN: That rate applies to all people – not just those who took an opioid. 1 in 67 deaths are due to opioid overdose, and benzos will raise that risk 2 to 4 fold. Here are some strategies to lower that risk for those in the yellow light

- Switch the benzo to oxazepam. This one has the lowest risk of accidental overdose because it has a short half life and is slow to come on – it takes effect over an hour instead of 20-30 minutes, which means it is less rewarding and less reinforcing. If you can’t switch to oxazepam, lorazepam (Ativan) is the second safest (Buckley NA et al, BMJ 1995;310(6974):219–221). Clonazepam (Klonopin), diazepam (Valium) and alprazolam (Xanax) are the worst – basically any benzo that is highly rewarding and lingers for a long time is bad news.

- Try alternatives. A lot of patients are reluctant to try alternatives when they are on a benzo, but you can enforce it by telling them you’re not able to prescribe the drug unless they give it an honest try. Think outside the box – SSRIs and Buspirone are not the only options for anxiety, and they don’t have a very large effect size. Pregabalin (Lyrica) has a larger effect size in generalized anxiety and social anxiety disorders, 300-600 mg/night, but this is not the ideal route as there is some evidence that it can increase the overdose rate as well. Consider CAM treatments like chamomile or Silexan – Silexan is a proprietary med in Germany that is extracted from lavender, and its effect size is comparable to that of benzos and much larger than SSRIs. Check out our August 2020 issue for full details. If your patient has bipolar disorder, quetiapine (Seroquel) and Depakote have evidence to help anxiety.

- Taper the benzo slowly, and get it down to zero or the lowest feasible dose. When assessing the need for a benzo, look at whether it is improving their functioning, not just their feeling. And is your use evidence based? The best evidence supporting benzo use is in Panic disorder, followed by generalized and social anxiety disorders. They are controversial in PTSD, and they don’t treat OCD, or ADHD for that matter. There are short term studies in depression and acute mania, but they aren’t indicated long-term in mood disorders.

- Believe in your patient. Benzodiazepine withdrawal is miserable, but if done slowly it is not dangerous. Patients will call you and try to convince you there is no possible way they can go on. Your job in those situations is not to raise the benzo but to believe in them – it will get better. Believe that simple interventions like mindfulness meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, deep breathing, stretching, exercise, and sleep hygiene will improve anxiety. Michael Otto developed a CBT therapy for benzo withdrawal, and there’s a patient guide and therapist’s guide available – Stopping Anxiety Medication.

- Check the controlled substance database, and coordinate with the physician who is prescribing the opioid. If you’re not comfortable prescribing the benzo, you can let that doctor know that you think it’s appropriate for the patient’s psychiatric condition but only if it’s managed by the same doctor who is prescribing the opioid. There is evidence that the risk of death is lower when one clinician manages both drugs. If that doctor is not comfortable prescribing the benzo, that may be a sign that you should not be either.

KELLIE NEWSOME: We’ll be back in 2 weeks with the 6th commandment – Controlled Substances Shall be Controlled, where we look at how to manage red flags of substance misuse with controlled prescriptions. Until then, catch us on Thursdays for a new edition of the Podcast stream – throwback Thursdays. We’re dusting off our old episodes, updating the content, and adding CME credits. And give yourself some CME credit for listening to this episode through the link on the show notes.

__________

The Carlat CME Institute is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Carlat CME Institute maintains responsibility for this program and its content. Carlat CME Institute designates this enduring material educational activity for a maximum of one quarter (.25) AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM. Physicians or psychologists should claim credit commensurate only with the extent of their participation in the activity.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)