Some of the people who revolutionized psychiatry lived with mental illness themselves.

Publication Date: 12/15/2025

Duration: 15 minutes, 15 seconds

Transcript:

KELLIE NEWSOME: Some of the people who revolutionized psychiatry struggled with psychiatric symptoms of their own. Starting with Freud and Jung. Welcome to The Carlat Psychiatry Podcast, keeping psychiatry honest since 2003.

CHRIS AIKEN: I’m Chris Aiken, the editor-in-chief of The Carlat Psychiatry Report.

KELLIE NEWSOME: And I’m Kellie Newsome, a psychiatric NP and a dedicated reader of every issue.

CHRIS AIKEN: In April of 2024, we released a series on wounded healers, interviewing psychiatrists, therapists, and nurse practitioners who live with their own mental illness: bipolar disorder, addiction, ADHD, panic disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. When I set out to do those interviews, I expected to find a deep well of empathy, a richer understanding of the disorders they treat. And I did. But I also found something else. These clinicians were not satisfied with the status quo. They knew what it’s like to live with lingering symptoms and persistent side effects, and they went the extra mile to make sure that didn’t happen to their patients, from intake to emergency calls. They set up their practices in patient-friendly ways. They knew how mental illness can hide behind walls of shame and disorder. Symptoms like suicidality, trauma, mania, addiction, even side effects that people keep secret so as not to disappoint us. They understood that patients don’t always tell us what we need to know, so they probed deeper, asking more questions. They did all the things that we all ought to be doing. They just did it very well. That Wounded Healer series has become one of our most popular, and today we have a coda. These are the wounded researchers. Like the clinicians we interviewed, they are not satisfied with the status quo. They aren’t even satisfied with doing their best with what we’ve got. These clinicians don’t just want to move the needle. They want to change the record, or maybe even shift from vinyl to compact disc. All researchers set out to improve the field, but many round out what is already there: reshaping CBT to treat a new anxiety disorder, or running clinical trials on a new antipsychotic or SSRI. That kind of incremental work is valuable, but it’s not what these episodes are about. These are the researchers who rocked the boat, challenging our basic assumptions about the disorders we treat, often at a cost to their own careers.

KELLIE NEWSOME: Let’s start with Sigmund Freud. Freud developed psychoanalysis to help his patients, but he also used it to heal his own neurosis. And in doing so, he carved out two traditions that are still with us today. One is the idea that we all have a little mental illness, captured by the title of Freud’s 1901 bestseller, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. The other is the idea that clinicians ought to go through their own therapy, so that touch of mental disorder doesn’t impair our work. But did Freud really suffer from clinical depression, or was he simply on the spectrum of everyday neurosis? The line between normal and pathological has moved so many times that it’s hard to say. But in his own writings, Freud described periods of inner agitation and depressive mood, obsessive preoccupations and rumination, palpitations, gastrointestinal distress, insomnia, guilt, and self-reproach. In 1897, he wrote to a friend: “I am depressed, anxious, and restless—physically and mentally incapable of work.” His letters from 1915 reflect the same trends, feeling unable to work, paralyzed by a painful melancholia, whatever their cause. Freud’s symptoms were severe enough to prompt treatment, not just with psychoanalysis, but with medication. While developing his theories in the 1880s, Freud self-medicated his dysthymic moods with cocaine, writing that small doses of the anesthetic lifted his spirits. He stopped when he realized the drug was addictive. Later, he used bromides and chloral hydrate, the benzos of the day, to alleviate anxiety and insomnia.

CHRIS AIKEN: Whether Freud’s dark moods inspired his discoveries or he sank deeper into that despair when his discoveries were met with failure, we don’t know. But we do know is that the 40-year-old Freud was in a triumphant mood on the morning of April 21, 1896, as he walked into the Vienna Society for Psychiatry and Neurology to deliver his first public lecture on psychoanalysis. As he laid out the sexual origins of hysteria, he imagined his colleagues would respond with admiration, surprise, or at the very least, a healthy debate. Instead, there was stone silence. No debate. No questions. Not even the perfunctory applause. His colleagues were interested in anatomy and physiology. They were not ready to hear about psychological causes for physical symptoms, much less causes rooted in sexual conflict and incestuous fantasies.

SIGMUND FREUD (archival audio)

KELLIE NEWSOME: Let’s pause for a preview of the CME quiz for this episode. Earn CME for each episode through the link in the show notes.

CHRIS AIKEN: I’m Chris Aiken, the editor-in-chief of The Carlat Psychiatry Report.

KELLIE NEWSOME: And I’m Kellie Newsome, a psychiatric NP and a dedicated reader of every issue.

CHRIS AIKEN: In April of 2024, we released a series on wounded healers, interviewing psychiatrists, therapists, and nurse practitioners who live with their own mental illness: bipolar disorder, addiction, ADHD, panic disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. When I set out to do those interviews, I expected to find a deep well of empathy, a richer understanding of the disorders they treat. And I did. But I also found something else. These clinicians were not satisfied with the status quo. They knew what it’s like to live with lingering symptoms and persistent side effects, and they went the extra mile to make sure that didn’t happen to their patients, from intake to emergency calls. They set up their practices in patient-friendly ways. They knew how mental illness can hide behind walls of shame and disorder. Symptoms like suicidality, trauma, mania, addiction, even side effects that people keep secret so as not to disappoint us. They understood that patients don’t always tell us what we need to know, so they probed deeper, asking more questions. They did all the things that we all ought to be doing. They just did it very well. That Wounded Healer series has become one of our most popular, and today we have a coda. These are the wounded researchers. Like the clinicians we interviewed, they are not satisfied with the status quo. They aren’t even satisfied with doing their best with what we’ve got. These clinicians don’t just want to move the needle. They want to change the record, or maybe even shift from vinyl to compact disc. All researchers set out to improve the field, but many round out what is already there: reshaping CBT to treat a new anxiety disorder, or running clinical trials on a new antipsychotic or SSRI. That kind of incremental work is valuable, but it’s not what these episodes are about. These are the researchers who rocked the boat, challenging our basic assumptions about the disorders we treat, often at a cost to their own careers.

KELLIE NEWSOME: Let’s start with Sigmund Freud. Freud developed psychoanalysis to help his patients, but he also used it to heal his own neurosis. And in doing so, he carved out two traditions that are still with us today. One is the idea that we all have a little mental illness, captured by the title of Freud’s 1901 bestseller, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. The other is the idea that clinicians ought to go through their own therapy, so that touch of mental disorder doesn’t impair our work. But did Freud really suffer from clinical depression, or was he simply on the spectrum of everyday neurosis? The line between normal and pathological has moved so many times that it’s hard to say. But in his own writings, Freud described periods of inner agitation and depressive mood, obsessive preoccupations and rumination, palpitations, gastrointestinal distress, insomnia, guilt, and self-reproach. In 1897, he wrote to a friend: “I am depressed, anxious, and restless—physically and mentally incapable of work.” His letters from 1915 reflect the same trends, feeling unable to work, paralyzed by a painful melancholia, whatever their cause. Freud’s symptoms were severe enough to prompt treatment, not just with psychoanalysis, but with medication. While developing his theories in the 1880s, Freud self-medicated his dysthymic moods with cocaine, writing that small doses of the anesthetic lifted his spirits. He stopped when he realized the drug was addictive. Later, he used bromides and chloral hydrate, the benzos of the day, to alleviate anxiety and insomnia.

CHRIS AIKEN: Whether Freud’s dark moods inspired his discoveries or he sank deeper into that despair when his discoveries were met with failure, we don’t know. But we do know is that the 40-year-old Freud was in a triumphant mood on the morning of April 21, 1896, as he walked into the Vienna Society for Psychiatry and Neurology to deliver his first public lecture on psychoanalysis. As he laid out the sexual origins of hysteria, he imagined his colleagues would respond with admiration, surprise, or at the very least, a healthy debate. Instead, there was stone silence. No debate. No questions. Not even the perfunctory applause. His colleagues were interested in anatomy and physiology. They were not ready to hear about psychological causes for physical symptoms, much less causes rooted in sexual conflict and incestuous fantasies.

SIGMUND FREUD (archival audio)

KELLIE NEWSOME: Let’s pause for a preview of the CME quiz for this episode. Earn CME for each episode through the link in the show notes.

1. What experimental method did Jung develop to probe the unconscious?

A. Subliminal reaction

B. Hypnosis

C. Word association test

D. Inkblot test

Over the next decade, Freud slowly built a following, drawing in disciples like Carl Jung. Freud had introduced the idea that seemingly random thoughts reveal unconscious motives, dreams, jokes, fantasies, and Freudian slips. Jung set out to test this experimentally, conducting word-association studies from the psychiatric hospital he directed in Zurich. He would show subjects a word and ask them to say the first word that came to mind, while measuring physiological responses like skin resistance and respiration. The idea was that long pauses or unusual reactions, such as laughing or repeating the original word, indicated unconscious conflict or complexes. This was the first scientific inquiry into Freud’s theory, arriving ten years before Rorschach’s inkblot test, which substituted the list of words with ambiguous inkblot patterns. Jung’s test is still in use today. In 2013, Australian researchers added brain imaging with an fMRI to the test. When a word triggered signs of unconscious conflict, the brain lit up in areas involved in self awareness, empathy, and conflict monitoring.B. Hypnosis

C. Word association test

D. Inkblot test

(archival audio of Carl Jung and interviewer): I went to Vienna for a fortnight, and then we had very long and penetrating conversations, and that settled it. And this long and penetrating conversation was followed by a personal friendship? Oh yes, it soon developed into a personal friendship. And what sort of man was Freud? Well, he was a complicated nature. I liked him very much, but I soon discovered that when he had thought something, then it was settled, while I was doubting all along the line.

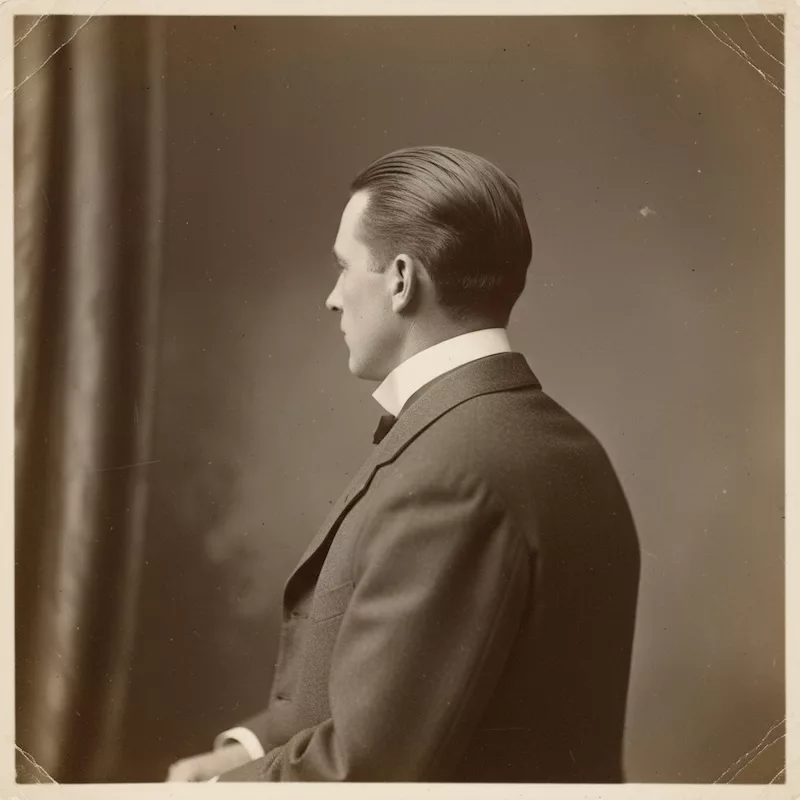

KELLIE NEWSOME: Jung sent his research to Freud, and the two met for the first time on March 3, 1907. They talked through the night, thirteen hours straight. The next day, the 50-year-old Freud called Jung, who was 30, his son and successor. It wasn’t just kinship of ideas. Freud’s inner circle was almost entirely Jewish, and critics were attacking psychoanalysis as a Jewish science. By raising up Carl Jung, he hoped to change that.

CHRIS AIKEN: Carl Jung was raised Protestant. His father was a minister in the Swiss Reformed Church, as were eight of his uncles. But as a child, his mother read to him from a book of world religions, and Jung identified more with the dream-like imagery of the Hindu gods than with his father’s faith. He came to see Protestantism as overly rational, his father’s sermons as stale, hollow, and inauthentic. The conflict reached a breaking point at Jung’s confirmation. Just as Judaism has the Barmitzvah, Prodastants have their own coming of age ceremony, the confirmation, in both cermemonies it represents the transition from the passive childlike acceptance of faith to an adult stance. There was one part of the confirmation ceremony that the 13-year-old Jung was looking forward to in particular: the Trinity, where he hoped to experience the mysterious union of God the Father, Jesus the Son, and the Holy Spirit. But when Jung’s father, who led the service, arrived at that intersection, he skipped over it, explaining to his son that no one really understands the Trinity, so it wasn’t worth going into. After that disappointment, Jung turned away from the church, but not from God. He delved into philosophy, mythology, dreams, visions, and world religions, trying to experience God directly and not through the rational lens of his father's church. Jung's religious journey mirrored his own psyche. He had intense imagination, with visions and mystical experiences. From an early age, Jung felt an otherworldly presence with visions of floods, disasters, and monsterous creatures in his head. A few years after meeting Freud, those visions began to border on the psychotic. He later said, “I was in the grip of images which I could not control, and I feared I was losing touch with reality.” Jung started talking to the spirits, and he also showed signs of bipolar disorder, sleeping only a few hours a night, fluctuating between hopelessness, despair, and this grandiose sense that by exploring these visions, he was fulfilling a personal mission from God that was going to change the world. At the same time, Jung feared he was losing his mind. Next week, we’ll look at how Jung resolved these symptoms in a way that reshaped psychotherapy. But first, let's look at the pioneers who came before Freud.

SIGMUND FREUD (archival audio)

CHRIS AIKEN: Freud is often credited with discovering the unconscious, but it wasn’t a new idea. Writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe had described the unconscious as the source of creativity, intuition, and irrational thought. German philosophers used the word ‘unconscious’ throughout the 1800s, and Freud was familiar with their work, like the 1869 book, The Philosophy of the Unconscious, by Eduard von Hartmann, which described internal conflict between the forces of desire and reason, much like the conflict Freud laid out with the ego and the id, years later. Nor was Freud the first to medicalize the idea. Pierre Janet, beat him to the punch, described how unbearable memories can split off into the unconscious, where they continue to thrash about, generating anxiety, compulsions, conversion disorder, and other psychiatric symptoms. It is from Janet’s theory that we get the idea of dissociation. Janet even developed a psychotherapeutic method to heal the split in the unconscious using hypnosis and suggestion to help the patient develop an integrative narrative. His ideas would strike a tone with many trauma-informed therapists today. Both men, Janet and Freud, were neurologists, born three years apart; Janet was younger, and both studied under Charcot, a french neurologist and hypnatist who discovered hystaria, what we now call conversion disorder. At first, Freud really credited Janet. But that changed in 1913, when Janet accused Freud of plagiarism, writing that Freud recycled old ideas, including his own. Freud never forgave Janrt. In 1937, when both men were nearing the end of their lives, and Nazi troops were burning Freud’s books in Vienna, Janet reached out to visit Freud at his home in Vienna. Freud refused him.

KELLIE NEWSOME: Dr. Aiken’s new book, Difficult to Treat Depression, is now available in print or as an audiobook, read to you by some familiar voices at Audible.com and Amazon. You’ll find practice guidance on novel strategies like celecoxib, pramipexole, and Auvelity, as well as time-honored wisdom on working with the avoidance, hopelessness, and traumatic life histories that are so common in chronic depression.

CHRIS AIKEN: Audio of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung was taken from BBC interviews conducted near the end of their lives, recorded in 1938 for Freud and 1959 for Jung.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)