Home » The Aging Brain: Preventing Cognitive Decline

The Aging Brain: Preventing Cognitive Decline

April 10, 2019

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

We’ve all been there. A 63-year-old patient comes to you with a chief complaint of memory loss. She tells you that she has a hard time remembering people’s names and forgets where she puts her keys. She lives and drives on her own without a problem, but asks, “Isn’t there some memory pill I can take?” What advice can we give her?

The first step is to differentiate what kind of memory problem is going on: normal aging or something more serious.

Normal aging

Cognitive decline begins around age 45 in healthy adults. The most common changes involve difficulties with attention and episodic and working memory. That means trouble multitasking, recalling conversations and events, and forgetting things on the to-do list. At first the decline is slow, but after age 65 the rate tends to double (Singh-Manoux A et al, BMJ 2012;344:d7622). The news is not all bad, however. Older adults perform better on tests that draw from experience, like judgment and problem solving (Dumas JA, Can J Psychiatry 2017;62(11):754–760).

Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorders

When cognitive decline slips beyond the normal level, a diagnosis of Mild or Major Neurocognitive Disorder may apply. Mild Neurocognitive Disorder is synonymous with mild cognitive impairment, but not with normal aging. The difference is that the deficits must be noticeable and require compensatory strategies or lifestyle changes. When those deficits keep the patient from living independently, another line is crossed, and the diagnosis would shift from Mild to Major Neurocognitive Disorder.

The Neurocognitive Disorders are new to DSM-5 and aim to broaden the recognition of these problems. They can be diagnosed at any age, regardless of the cause, as long as it’s not due to another mental disorder like depression or schizophrenia. Toxicity from past substance abuse, however, is allowed in the diagnosis. The cause may be unknown, or it can include dementia, traumatic brain injury, stroke, infection, or another medical illness.

Although dementia tends to be progressive, Mild Neurocognitive Disorder is usually not. Only 10%–15% progress to dementia, while another 15%–30% actually regain their functioning after a year (Sachs-Ericsson N et al, Aging Ment Health 2015;19(1):2–12).

Screening tests can also help distinguish normal aging from a Neurocognitive Disorder. The popular Mini Mental Status Exam is being replaced by more sensitive tests like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) and the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination (SLUMS). Both of these can be completed in 10 minutes and are normed for Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorders. An abbreviated form of the SLUMS, the Rapid Cognitive Screen, can be administered in 5 minutes. (Sanford AM, Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33(3):325–337).

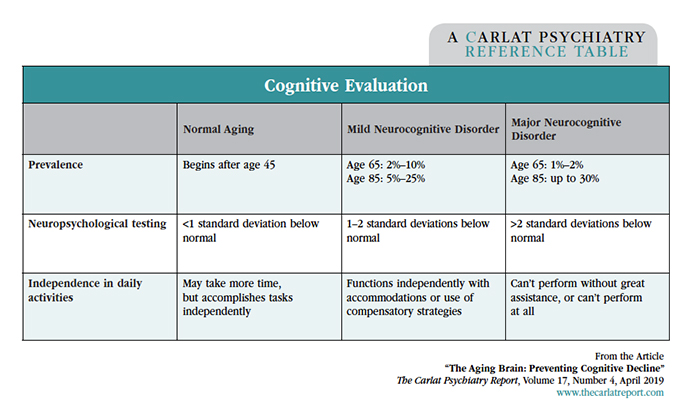

If you suspect a Neurocognitive Disorder in your patient, further workup is in order. See the table below to assist you in your cognitive evaluation. Also, for a concise review, see “Determining Dementia” in the May 2017 issue of TCPR.

Sharpening cognition

For patients who notice some cognitive decline but don’t show substantial impairments, what advice can we give them? There are no FDA-approved medications, nor are there any recommendable medicines. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may slow the progression of dementia, but they aren’t recommended for normal aging. Even their use in Mild Neurocognitive Disorder is controversial as they don’t seem to prevent the progression to dementia (Sanford AM, Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33(3):325–337).

Instead, reducing unnecessary medications is the first step. Common medications that can impair cognition include benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, opioids, muscle relaxants, anticholinergics (which include antihistamines, paroxetine, tricyclics, antipsychotics, and urinary incontinence medications), and those that cause low blood pressure or orthostasis.

Next, encourage patients to address physical factors that impair cognition. Think cardiovascular and metabolic: obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, sleep apnea, and hypertension. Low blood pressure (<120/75 mm Hg) is also a problem. Although cognitive decline itself may cause hypotension, overly aggressive treatment of blood pressure has also been linked to worsened cognitive outcomes (Mossello E et al, JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(4):578–585).

Lifestyle interventions are also effective, and the top three are diet, exercise, and cognitive training.

Diet

The MIND diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) is a combination of the Mediterranean and DASH diets that slows the rate of cognitive decline in older adults (Morris MC et al, Alzheimers Dement 2015;11(9):1015–1022). It focuses on consumption of vegetables (especially the green, leafy kind), berries, whole grains, seafood, chicken, and healthy fats (olive oil and nuts). It limits red meat, butter, cheese, refined sugar, and fried or fast foods. The diet’s creator, Martha Clare Morris, has a good book for patients, Diet for the MIND (2017).

Exercise

The other component of lifestyle modifications is exercise—but what should we recommend out of the countless programs available? A recent meta-analysis reviewed 39 studies involving a variety of exercise types, from tai chi to strength training, for adults age 50+ (Northey JM et al, Br J Sports Med 2018;52(3):154–160). Nearly all modalities had positive effects, but the most robust evidence was for multicomponent programs—those that combine aerobic and resistance training. Optimal session length was 45–60 minutes, 5–7 days a week with moderate to vigorous intensity. That’s a substantial time commitment. Exercising only 1 or 2 days a week still has significant results, but the more days of exercise the better.

Cognitive training

Cognitive training programs have a history of exaggerated claims. Lumosity is the most popular, but it is thin on research, and in 2016 it was fined $2 million by the Federal Trade Commission for false advertising. Other programs have had more success. In mild cognitive impairment, they improve most domains except for processing speed and executive functioning, according to a meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials. The effect size was medium, which means the improvement would be apparent to the casual observer (Hill NT et al, Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(4):329–340).

It’s less clear how the gains from repeated practice translate into everyday life. Mood and quality of life improved with these programs, but not activities of daily living. The real world is also full of opportunities that probably work just as well as digital interventions. Those include playing cards, word games, sudoku, jigsaw puzzles, and musical instruments, as well as meaningful hobbies and social interactions (Sanford AM, Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33(3):325–337).

Most of the effective cognitive training programs involved sessions of 30–90 minutes 2–3 times a week. Games of dexterity work as well as the more cerebral kind. Most of the well-researched programs are not available to the public. Among the few that are, good options include BrainHQ, Nintendo’s Wii Sports (especially Bowling), and Nintendo’s Big Brain Academy.

TCPR Verdict: The best way to combat cognitive decline is to attend to the health of the brain. That means sleep, diet, exercise, and measures that improve physical health. Social activities, hobbies, and mental challenges preserve cognition, and when these opportunities are lacking, a computerized training program can help.

In Summary

General PsychiatryThe first step is to differentiate what kind of memory problem is going on: normal aging or something more serious.

Normal aging

Cognitive decline begins around age 45 in healthy adults. The most common changes involve difficulties with attention and episodic and working memory. That means trouble multitasking, recalling conversations and events, and forgetting things on the to-do list. At first the decline is slow, but after age 65 the rate tends to double (Singh-Manoux A et al, BMJ 2012;344:d7622). The news is not all bad, however. Older adults perform better on tests that draw from experience, like judgment and problem solving (Dumas JA, Can J Psychiatry 2017;62(11):754–760).

Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorders

When cognitive decline slips beyond the normal level, a diagnosis of Mild or Major Neurocognitive Disorder may apply. Mild Neurocognitive Disorder is synonymous with mild cognitive impairment, but not with normal aging. The difference is that the deficits must be noticeable and require compensatory strategies or lifestyle changes. When those deficits keep the patient from living independently, another line is crossed, and the diagnosis would shift from Mild to Major Neurocognitive Disorder.

The Neurocognitive Disorders are new to DSM-5 and aim to broaden the recognition of these problems. They can be diagnosed at any age, regardless of the cause, as long as it’s not due to another mental disorder like depression or schizophrenia. Toxicity from past substance abuse, however, is allowed in the diagnosis. The cause may be unknown, or it can include dementia, traumatic brain injury, stroke, infection, or another medical illness.

Although dementia tends to be progressive, Mild Neurocognitive Disorder is usually not. Only 10%–15% progress to dementia, while another 15%–30% actually regain their functioning after a year (Sachs-Ericsson N et al, Aging Ment Health 2015;19(1):2–12).

Screening tests can also help distinguish normal aging from a Neurocognitive Disorder. The popular Mini Mental Status Exam is being replaced by more sensitive tests like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) and the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination (SLUMS). Both of these can be completed in 10 minutes and are normed for Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorders. An abbreviated form of the SLUMS, the Rapid Cognitive Screen, can be administered in 5 minutes. (Sanford AM, Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33(3):325–337).

If you suspect a Neurocognitive Disorder in your patient, further workup is in order. See the table below to assist you in your cognitive evaluation. Also, for a concise review, see “Determining Dementia” in the May 2017 issue of TCPR.

Table: Cognitive Evaluation

Sharpening cognition

For patients who notice some cognitive decline but don’t show substantial impairments, what advice can we give them? There are no FDA-approved medications, nor are there any recommendable medicines. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may slow the progression of dementia, but they aren’t recommended for normal aging. Even their use in Mild Neurocognitive Disorder is controversial as they don’t seem to prevent the progression to dementia (Sanford AM, Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33(3):325–337).

Instead, reducing unnecessary medications is the first step. Common medications that can impair cognition include benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, opioids, muscle relaxants, anticholinergics (which include antihistamines, paroxetine, tricyclics, antipsychotics, and urinary incontinence medications), and those that cause low blood pressure or orthostasis.

Next, encourage patients to address physical factors that impair cognition. Think cardiovascular and metabolic: obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, sleep apnea, and hypertension. Low blood pressure (<120/75 mm Hg) is also a problem. Although cognitive decline itself may cause hypotension, overly aggressive treatment of blood pressure has also been linked to worsened cognitive outcomes (Mossello E et al, JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(4):578–585).

Lifestyle interventions are also effective, and the top three are diet, exercise, and cognitive training.

Diet

The MIND diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) is a combination of the Mediterranean and DASH diets that slows the rate of cognitive decline in older adults (Morris MC et al, Alzheimers Dement 2015;11(9):1015–1022). It focuses on consumption of vegetables (especially the green, leafy kind), berries, whole grains, seafood, chicken, and healthy fats (olive oil and nuts). It limits red meat, butter, cheese, refined sugar, and fried or fast foods. The diet’s creator, Martha Clare Morris, has a good book for patients, Diet for the MIND (2017).

Exercise

The other component of lifestyle modifications is exercise—but what should we recommend out of the countless programs available? A recent meta-analysis reviewed 39 studies involving a variety of exercise types, from tai chi to strength training, for adults age 50+ (Northey JM et al, Br J Sports Med 2018;52(3):154–160). Nearly all modalities had positive effects, but the most robust evidence was for multicomponent programs—those that combine aerobic and resistance training. Optimal session length was 45–60 minutes, 5–7 days a week with moderate to vigorous intensity. That’s a substantial time commitment. Exercising only 1 or 2 days a week still has significant results, but the more days of exercise the better.

Cognitive training

Cognitive training programs have a history of exaggerated claims. Lumosity is the most popular, but it is thin on research, and in 2016 it was fined $2 million by the Federal Trade Commission for false advertising. Other programs have had more success. In mild cognitive impairment, they improve most domains except for processing speed and executive functioning, according to a meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials. The effect size was medium, which means the improvement would be apparent to the casual observer (Hill NT et al, Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(4):329–340).

It’s less clear how the gains from repeated practice translate into everyday life. Mood and quality of life improved with these programs, but not activities of daily living. The real world is also full of opportunities that probably work just as well as digital interventions. Those include playing cards, word games, sudoku, jigsaw puzzles, and musical instruments, as well as meaningful hobbies and social interactions (Sanford AM, Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33(3):325–337).

Most of the effective cognitive training programs involved sessions of 30–90 minutes 2–3 times a week. Games of dexterity work as well as the more cerebral kind. Most of the well-researched programs are not available to the public. Among the few that are, good options include BrainHQ, Nintendo’s Wii Sports (especially Bowling), and Nintendo’s Big Brain Academy.

TCPR Verdict: The best way to combat cognitive decline is to attend to the health of the brain. That means sleep, diet, exercise, and measures that improve physical health. Social activities, hobbies, and mental challenges preserve cognition, and when these opportunities are lacking, a computerized training program can help.

In Summary

- Cognition tends to decline after age 45. Usually this is due to normal aging, but if the decline is more extreme, a diagnosis of Mild or Major Neurocognitive Disorder may apply.

- Only a minority of Mild Neurocognitive Disorder cases progress to dementia, and cholinesterase inhibitors are not recommended in these cases as they don’t help to slow the decline.

- Reducing unnecessary medications, addressing physical health risks, and incorporating lifestyle interventions can help to sharpen cognition as people age.

Issue Date: April 10, 2019

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)