Are Auditory Hallucinations Ever Normal?

When a patient presents with auditory hallucinations (AH), are you likely to diagnose a psychotic disorder? If no other symptoms are present, would you recommend an antipsychotic? If you answered yes to either question, there’s some new research that may change your mind. Hearing voices may be a common experience for people without mental illness. Is it time to stop equating voice-hearing with psychosis?

How common is voice-hearing?

When people say they “hear voices,” they may be describing a wide range of experiences beyond the traditional definition of auditory verbal hallucinations.

When questionnaires are used to survey the general population about “hearing a voice as if someone had spoken when no one was there” or “hearing voices that other people said did not exist,” about 5%–15% report AH at some point in their lives. This isn’t surprising, given that while AH are generally thought of as a hallmark of psychosis, they also occur in a wide range of non-psychotic disorders (Pierre JM, Harv Rev Psychiatry 2010;18(1):22–35).

But AH are also reported in adults without any other evidence of a psychiatric disorder. Just how common are these “normal voice-hearers”? That’s open to debate. Some surveys have detected extraordinarily high rates, such as 60%–80% in some samples of college students or psychiatric nurses who otherwise had no evidence of mental illness (Beaven V et al, J Ment Health 2011;20(3):281–292). Those studies have notable flaws, however, such as relying on written surveys with ambiguously phrased questions and failing to rule out drug-induced and sleep-related hallucinations. Hallucinations that occur while falling asleep (hypnogogic) or waking (hypnopompic) are not considered psychotic; they may be a sign of a sleep disorder or just a part of normal experience.

A more conservative estimate is that healthy voice-hearers make up 1%–3% of the population worldwide. That’s the rate arrived at when using face-to-face structured interviews to ask about non-distressing AH and excluding those with psychotic disorders, drug-induced experiences, and sleep-related phenomena.

Normal vs pathological

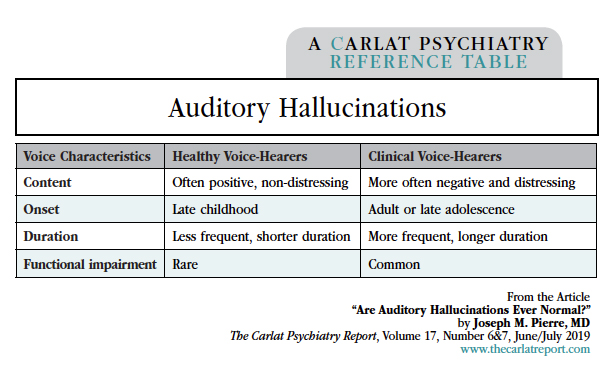

How do healthy voices differ from pathological ones? The research on this is extensive, encompassing several thousand patients across 36 studies (Baumeister D et al, Clin Psychol Rev 2017;51:125–141). Key differences are that healthy voices are less distressing and more likely to involve positive comments, such as a guardian angel telling a person to keep pressing on. Notably, the two groups do not differ in the number of voices, their loudness, or their localization (eg, inside or outside of the head). Nor do they differ based on neuroimaging studies, which have found that fMRI activation during voice-hearing is indistinguishable between healthy and clinical voice-hearers.

Healthy voice-hearers are more likely than clinical voice-hearers to attribute their voices to an external source, often within a spiritual framework. This finding matches an illustrative case found in one of the first published studies of healthy voice-hearers. It described a 42-year-old woman living in the Netherlands who had no mental illness but had heard voices dating back to childhood. She was “in private practice as a psychic healer” and described communicating with her voices and consulting with them “for the benefit of herself or her clients.” She found her voices comforting and helpful, characterizing them as “protective ghosts” (Honig A et al, J Nerv Ment Dis 1998;186(10):646–651).

This example mirrors a recent study that concluded that self-identified “clairaudient psychics,” who believe that they “receive auditory messages from spirits” but are otherwise free of mental illness, may represent a typical example of healthy voice-hearers who interpret their voices within a sanctioned, and perhaps even adaptive, cultural context (Powers AR et al, Schizophr Bull 2017;43(1):84–98). Such cases are reminiscent of Carl Jung’s writings, where he described his conversations with a “spirit guide” called Philemon. Stanford anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann described normal voice-hearers as “people who lose themselves in nature, become captivated by books, or pray ardently—in other words, people who get caught up in their inner worlds” (https://tinyurl.com/ycush83h).

Just how “healthy” are healthy voice-hearers?

In the research reviewed above, healthy voice-hearers were recruited from the general population and had no history of mental illness or psychiatric treatment, either by self-report or diagnostic interview. However, several studies comparing healthy voice-hearers to healthy controls who did not hear voices found evidence of schizotypal traits such as delusion-like beliefs, magical thinking, and formal thought disorder (but the voice-hearers did not meet full criteria for schizotypal personality disorder). On cognitive tests, healthy voice-hearers tend to perform at the lower end of the normal range. This suggests that while they may not have mental illness per se, they lie somewhere on a psychotic spectrum.

Another enduring finding is that a history of childhood sexual abuse is overrepresented among both healthy voice-hearers and clinical voice-hearers. While a causal relationship has not been established, childhood abuse may be an important risk factor for voice-hearing. Hallucinations could be a distressing consequence of childhood trauma in clinical cases, but also a potentially adaptive coping mechanism in healthy voice-hearers.

Although AH in people without mental disorders can be normal, there’s reason to think they warrant clinical monitoring. A recent prospective study followed healthy voice-hearers who had no mental illness and didn’t need mental health treatment at baseline. After 5 years, 40% of the sample went on to require care and were eventually diagnosed with a range of mental disorders, including not only psychotic disorders but also bipolar disorder, depression, PTSD, ADHD, and autism (Daalman K et al, Psychol Med 2016;46(9):1897–1907). While voice-hearing can occur without evidence of mental illness, it may also be an early sign of a developing psychiatric disorder.

Clinical recommendations

When asking patients about voice-hearing, you should first distinguish between AH and other non-hallucinatory experiences. “Voices” may represent one’s conscience or inner voice, depressive ruminations, metaphorical expressions, idioms of distress, or malingering. Those kinds of experiences shouldn’t be mistaken for psychosis and can respond to supportive psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy without antipsychotics (Pierre JM et al, Biol Psychiatr 2010;68(7):e33–e34).

When voices sound like genuine hallucinations, but are non-distressing and occur without other psychiatric symptoms, no intervention may be necessary. However, for patients in their teens or early twenties with a family history of psychosis or personal history of drug use (including cannabis), careful monitoring is in order. These patients are at risk for progression to psychosis. Finally, when patients with psychotic disorders like schizophrenia report distressing AH, an antipsychotic trial is clearly indicated. In this population, AH often respond well to pharmacotherapy, though this is certainly not always the case. Other interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy may help relieve distress.

Self-help groups have emerged for healthy voice-hearers that provide support in a non-judgmental environment. These groups encourage a de-stigmatized (and often de-medicalized) understanding of voice-hearing experiences (eg, www.hearing-voices.org). For voice-hearers at the healthier end of the continuum, they offer much-welcomed reassurance and acceptance. I view these groups much like I do Alcoholics Anonymous—complementary treatments that can be a vital source of psychosocial support and sometimes psychotherapy, but can also be harmful if they encourage the rejection of psychiatric care for voice-hearers with clear mental illness.

TCPR Take: Hallucinations are like coughs. They range in severity from normal and insignificant to a pathological symptom of a life-threatening disease like schizophrenia. Like a cough, hallucinations might warrant no intervention, cautious monitoring, or specific treatment, depending on your full assessment.

Table: Auditory Hallucinations

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)