Home » Motivational Interviewing With Teens About Weed

Motivational Interviewing With Teens About Weed

October 3, 2019

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Elizabeth D’Amico, PhD

Elizabeth D’Amico, PhD

Senior Behavioral Scientist at RAND and member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT)

Dr. D’Amico has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

With motivational interviewing (MI), people are more likely to accept and act when they feel ownership; MI is specifically helpful for teens, who are at an age where they do not want suggestions from others. We spoke with Dr. Elizabeth D’Amico, nationally recognized for her work developing, implementing, and evaluating interventions for adolescents, about the benefits of applying MI to marijuana use in teens.

CCPR: Tell us a little bit about your background.

Dr. D’Amico: My focus has been on community-based research, working with communities around prevention for alcohol and other drug use and risky sexual behavior. I work in middle schools, teen courts, homeless shelters, and primary care, and I do prevention work with urban Native American youth across California.

CCPR: Help us understand the scope of marijuana use in teens and how it impacts overall function.

Dr. D’Amico: Research is mixed. A recent study found cannabis use was not associated with structural brain differences in adulthood (Meier MH et al, Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;202:191–219). However, other work shows that teens who use cannabis frequently are more likely to do poorly on memory tests and higher-level problem solving and information processing (Morin JFG et al, Am J Psychiatry 2018;176(2):98–106).

CCPR: A lot of kids will say marijuana is pretty safe stuff because it’s legal.

Dr. D’Amico: Cannabis has been marketed as medical, so people’s views of it are different than alcohol. Most people would say “I would never drink and drive.” But we hear teens say “Cannabis helps me focus and it’s safe,” yet we know that THC can alter their behavior.

CCPR: How do we advise psychiatrists given this set of circumstances?

Dr. D’Amico: Psychiatrists should screen for both cannabis and alcohol. Our large longitudinal study has shown that teens have more problems from marijuana than alcohol—academically, with mental health, and with delinquency (D’Amico EJ et al, Addiction 2016;111(10):1825–1835). In our primary care study, we found that rates of cannabis use disorder were three times as high as for alcohol use disorder (D’Amico EJ et al, Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20161717).

CCPR: Do you have a recommended set of screening practices that make sense?

Dr. D’Amico: Yes. In our study we found that the CRAFFT best captured both alcohol and cannabis problem use and disorders. CRAFFT consists of 6 questions and is freely available at www.tinyurl.com/yxn8djnf (see part B). (Editor’s note: For more information on the CRAFFT screening tool, see www.thecarlatreport.com/CRAFFT.)

CCPR: That’s good to know. Before we get into specifics on applying MI, please give us your take on what it is.

Dr. D’Amico: MI is a collaborative approach. You work with teens to guide them to make a healthy choice, if they’re ready. Not everybody’s ready. We’re not telling people “You need to stop,” because when we do that, people typically react: “No way! I’m never going to stop!” MI is a guided approach to help people think through the pros and cons of using, how they balance that out, and whether it makes sense for them to make a change in their behavior.

CCPR: So, once we see that there is a problem, we ought to do MI?

Dr. D’Amico: Yes. There’s an online training for providers that I developed with the National Institute of Drug Abuse (http://training.simmersion.com/). In this training, if a teen comes into your office reporting marijuana use, you as the provider try to use MI to determine the teen’s level of use and what needs to be done. Busy providers don’t have time to sit through an all-day training session. This is a way to learn MI efficiently, and you can get continuing education for it.

CCPR: What do teens think about MI?

Dr. D’Amico: In our primary care study, teens were coming in for a primary care appointment—a cold or a physical—but they were willing to talk about substance use. Many wanted to make changes, too. It helped them to talk about what it would mean, for their future and what they hoped to accomplish, if they continued using.

CCPR: Are there differences for psychiatrists? A lot of times the subject of substance use is already on the table because the teens’ parents bring the kids to us to address it.

Dr. D’Amico: It’s the same. Kids are using because maybe it helps them sleep, or they’re getting pressure from friends. Maybe it’s anxiety, and they feel it helps them. It’s important to understand the good things they get from using and the not-so-good things. The good usually doesn’t outweigh the not-so-good, and they can see that on their own. You might reflect back: “It’s really fun for you to use and you love hanging out with your friends, and yet you’ve gotten in a lot of trouble with your parents and your grades are dropping.” MI works well when someone is ambivalent about a behavior.

CCPR: When patients tell us they use marijuana to feel good and/or to fit in with friends, how do you apply MI?

Dr. D’Amico: Those are the main reasons we hear. For a teen who is very influenced by friends, you might ask: “How confident are you to not use around your friends on Friday, since you said you wanted to cut back on your use?” For others, it might be: “How confident are you to try other ways to get to sleep without using?” If they’re ready to make a change, we discuss how they could make that happen.

CCPR: They often say they want to stop, but it’s really hard.

Dr. D’Amico: Really hard. If teens can cut back to using once a week vs every day, I think that’s a great outcome. They’re still using, but it’s probably not going to affect them as much. I go with what they think they can handle as a starting point.

CCPR: So, harm reduction is okay.

Dr. D’Amico: Right. Teens are not going to walk out of the office and never use cannabis again. That’s not going to happen. But it’s a good outcome if they avoid using before driving or they don’t get in a car with someone who’s using. Or maybe they stopped using during school hours, and they’re getting their homework done. They might still use with their friends on a Friday—but overall, because they cut back, their consequences are significantly reduced in terms of academics, mental health, and physical health. You have to start somewhere.

CCPR: What about parents’ expectations that their teen will stop altogether?

Dr. D’Amico: Let them know it depends on whether the teen is using to such an extent that maybe there’s a need for more intensive treatment. Brief MI interventions are for teens who are at risk, maybe starting to use more regularly, to catch them and help them change their use.

CCPR: How do you decide when somebody needs a referral for treatment?

Dr. D’Amico: Every teen is different. If a teen is using every day, not going to school, having a lot of problems, that person needs more than a 15-minute intervention. What was fascinating in our research is that teens who came in with more negative consequences from marijuana benefited more from the brief intervention than teens in usual care. But when we had teens come in who weren’t experiencing a lot of consequences from marijuana, they actually did better in usual care. We think this is because with MI, the focus is on whether or not you’re ready to make a change, and if teens are not experiencing a lot of consequences, they may not be ready to make a change in their use.

CCPR: What is “usual care”?

Dr. D’Amico: In our study, we gave teens a brochure with information about marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs, plus several websites and numbers to get more information.

CCPR: So, if you have somebody who comes in who has more bad things happening, MI makes sense. Otherwise you might do some psychoeducation with the teen, and that actually might be more effective.

Dr. D’Amico: Right. You can frame it as building the teen’s self-efficacy for the future: “If you were having problems, what would you do?” You could talk about strategies to recognize when problems are developing so the teen knows when change is needed.

CCPR: What’s the time frame for MI when you’re working on harm reduction with a patient who is using to some degree?

Dr. D’Amico: We did one-time 15-minute brief interventions. Teens who were experiencing more consequences often reduced their use and consequences one year later (D’Amico EJ et al, Pediatrics 2019;144(2):e20183014). But if you check in with them in a few months and find they didn’t make changes, ask: Why not? Are they ready to make changes now? How might they do that? Work on their coping skills. We ask patients how motivated they are to change their use, and how confident they are to change. Really motivated teens who aren’t confident will need skills training; teens who aren’t motivated to change, but are confident they could, require a different conversation.

CCPR: Sometimes it’s almost as if they don’t have the will or the ability to make the changes that we’re talking about.

Dr. D’Amico: Kids will say “Yeah, this is affecting me, but I really like using pot.” That’s where you can step in and reflect this ambivalence. You could also say “Well, if it’s OK with you, can I share some strategies other teens have tried?” You might suggest that they try to only use on the weekend or hang around other teens that don’t use. Some of them are going to need treatment, and this brief intervention won’t work. But for most teens at risk, it’s a perfect approach to get them to think about their behavior.

CCPR: Does the training address this?

Dr. D’Amico: In the training, if you pick the wrong things to say to the patient, he will completely shut down and not tell you anything, just like what might happen in an actual appointment. It’s based on real-life situations.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. D’Amico.

Child PsychiatryCCPR: Tell us a little bit about your background.

Dr. D’Amico: My focus has been on community-based research, working with communities around prevention for alcohol and other drug use and risky sexual behavior. I work in middle schools, teen courts, homeless shelters, and primary care, and I do prevention work with urban Native American youth across California.

CCPR: Help us understand the scope of marijuana use in teens and how it impacts overall function.

Dr. D’Amico: Research is mixed. A recent study found cannabis use was not associated with structural brain differences in adulthood (Meier MH et al, Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;202:191–219). However, other work shows that teens who use cannabis frequently are more likely to do poorly on memory tests and higher-level problem solving and information processing (Morin JFG et al, Am J Psychiatry 2018;176(2):98–106).

CCPR: A lot of kids will say marijuana is pretty safe stuff because it’s legal.

Dr. D’Amico: Cannabis has been marketed as medical, so people’s views of it are different than alcohol. Most people would say “I would never drink and drive.” But we hear teens say “Cannabis helps me focus and it’s safe,” yet we know that THC can alter their behavior.

CCPR: How do we advise psychiatrists given this set of circumstances?

Dr. D’Amico: Psychiatrists should screen for both cannabis and alcohol. Our large longitudinal study has shown that teens have more problems from marijuana than alcohol—academically, with mental health, and with delinquency (D’Amico EJ et al, Addiction 2016;111(10):1825–1835). In our primary care study, we found that rates of cannabis use disorder were three times as high as for alcohol use disorder (D’Amico EJ et al, Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20161717).

CCPR: Do you have a recommended set of screening practices that make sense?

Dr. D’Amico: Yes. In our study we found that the CRAFFT best captured both alcohol and cannabis problem use and disorders. CRAFFT consists of 6 questions and is freely available at www.tinyurl.com/yxn8djnf (see part B). (Editor’s note: For more information on the CRAFFT screening tool, see www.thecarlatreport.com/CRAFFT.)

CCPR: That’s good to know. Before we get into specifics on applying MI, please give us your take on what it is.

Dr. D’Amico: MI is a collaborative approach. You work with teens to guide them to make a healthy choice, if they’re ready. Not everybody’s ready. We’re not telling people “You need to stop,” because when we do that, people typically react: “No way! I’m never going to stop!” MI is a guided approach to help people think through the pros and cons of using, how they balance that out, and whether it makes sense for them to make a change in their behavior.

CCPR: So, once we see that there is a problem, we ought to do MI?

Dr. D’Amico: Yes. There’s an online training for providers that I developed with the National Institute of Drug Abuse (http://training.simmersion.com/). In this training, if a teen comes into your office reporting marijuana use, you as the provider try to use MI to determine the teen’s level of use and what needs to be done. Busy providers don’t have time to sit through an all-day training session. This is a way to learn MI efficiently, and you can get continuing education for it.

CCPR: What do teens think about MI?

Dr. D’Amico: In our primary care study, teens were coming in for a primary care appointment—a cold or a physical—but they were willing to talk about substance use. Many wanted to make changes, too. It helped them to talk about what it would mean, for their future and what they hoped to accomplish, if they continued using.

CCPR: Are there differences for psychiatrists? A lot of times the subject of substance use is already on the table because the teens’ parents bring the kids to us to address it.

Dr. D’Amico: It’s the same. Kids are using because maybe it helps them sleep, or they’re getting pressure from friends. Maybe it’s anxiety, and they feel it helps them. It’s important to understand the good things they get from using and the not-so-good things. The good usually doesn’t outweigh the not-so-good, and they can see that on their own. You might reflect back: “It’s really fun for you to use and you love hanging out with your friends, and yet you’ve gotten in a lot of trouble with your parents and your grades are dropping.” MI works well when someone is ambivalent about a behavior.

CCPR: When patients tell us they use marijuana to feel good and/or to fit in with friends, how do you apply MI?

Dr. D’Amico: Those are the main reasons we hear. For a teen who is very influenced by friends, you might ask: “How confident are you to not use around your friends on Friday, since you said you wanted to cut back on your use?” For others, it might be: “How confident are you to try other ways to get to sleep without using?” If they’re ready to make a change, we discuss how they could make that happen.

CCPR: They often say they want to stop, but it’s really hard.

Dr. D’Amico: Really hard. If teens can cut back to using once a week vs every day, I think that’s a great outcome. They’re still using, but it’s probably not going to affect them as much. I go with what they think they can handle as a starting point.

CCPR: So, harm reduction is okay.

Dr. D’Amico: Right. Teens are not going to walk out of the office and never use cannabis again. That’s not going to happen. But it’s a good outcome if they avoid using before driving or they don’t get in a car with someone who’s using. Or maybe they stopped using during school hours, and they’re getting their homework done. They might still use with their friends on a Friday—but overall, because they cut back, their consequences are significantly reduced in terms of academics, mental health, and physical health. You have to start somewhere.

CCPR: What about parents’ expectations that their teen will stop altogether?

Dr. D’Amico: Let them know it depends on whether the teen is using to such an extent that maybe there’s a need for more intensive treatment. Brief MI interventions are for teens who are at risk, maybe starting to use more regularly, to catch them and help them change their use.

CCPR: How do you decide when somebody needs a referral for treatment?

Dr. D’Amico: Every teen is different. If a teen is using every day, not going to school, having a lot of problems, that person needs more than a 15-minute intervention. What was fascinating in our research is that teens who came in with more negative consequences from marijuana benefited more from the brief intervention than teens in usual care. But when we had teens come in who weren’t experiencing a lot of consequences from marijuana, they actually did better in usual care. We think this is because with MI, the focus is on whether or not you’re ready to make a change, and if teens are not experiencing a lot of consequences, they may not be ready to make a change in their use.

CCPR: What is “usual care”?

Dr. D’Amico: In our study, we gave teens a brochure with information about marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs, plus several websites and numbers to get more information.

CCPR: So, if you have somebody who comes in who has more bad things happening, MI makes sense. Otherwise you might do some psychoeducation with the teen, and that actually might be more effective.

Dr. D’Amico: Right. You can frame it as building the teen’s self-efficacy for the future: “If you were having problems, what would you do?” You could talk about strategies to recognize when problems are developing so the teen knows when change is needed.

CCPR: What’s the time frame for MI when you’re working on harm reduction with a patient who is using to some degree?

Dr. D’Amico: We did one-time 15-minute brief interventions. Teens who were experiencing more consequences often reduced their use and consequences one year later (D’Amico EJ et al, Pediatrics 2019;144(2):e20183014). But if you check in with them in a few months and find they didn’t make changes, ask: Why not? Are they ready to make changes now? How might they do that? Work on their coping skills. We ask patients how motivated they are to change their use, and how confident they are to change. Really motivated teens who aren’t confident will need skills training; teens who aren’t motivated to change, but are confident they could, require a different conversation.

CCPR: Sometimes it’s almost as if they don’t have the will or the ability to make the changes that we’re talking about.

Dr. D’Amico: Kids will say “Yeah, this is affecting me, but I really like using pot.” That’s where you can step in and reflect this ambivalence. You could also say “Well, if it’s OK with you, can I share some strategies other teens have tried?” You might suggest that they try to only use on the weekend or hang around other teens that don’t use. Some of them are going to need treatment, and this brief intervention won’t work. But for most teens at risk, it’s a perfect approach to get them to think about their behavior.

CCPR: Does the training address this?

Dr. D’Amico: In the training, if you pick the wrong things to say to the patient, he will completely shut down and not tell you anything, just like what might happen in an actual appointment. It’s based on real-life situations.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. D’Amico.

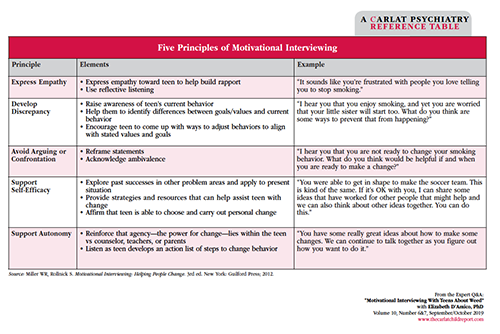

Table: Five Principles of Motivational Interviewing

Click to view full-size PDF.

KEYWORDS cannabis marijuana motivational-interviewing outpatient primary-care substance-use-disorders teens weed

Issue Date: October 3, 2019

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)