Home » Growing Rate of Suicide in Teens: Assessment and Prevention

Growing Rate of Suicide in Teens: Assessment and Prevention

October 3, 2019

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Clinicians treating children and adolescents regularly encounter patients with suicidal thoughts. And with rising rates of adolescent suicide and shrinking inpatient stays, we’re seeing more of these suicidal kids in our offices. This article examines some of the novel risk factors and offers management and prevention strategies for you to consider utilizing in your clinical practice.

Rising trends

Although suicide rates fell in the 1990s, they started rising in 2007. The rate of suicide and preferred method differs by age.

10–14 years old: Between 2007 and 2015, the suicide rate increased slightly in boys (from 2.3 to 2.5 per 100k) but tripled in girls (from 0.6 to 1.7 per 100k). While death by suffocation and firearms was almost equal in boys (48% each), 70% of girls died by suffocation (Hedegaard H et al, NCHS Data Brief 2018;309:1–8).

15–19 years old: The suicide rate increased 31% for boys (from 10.8 to 14.2 per 100k) and more than doubled for girls (from 2.4 to 5.1 per 100k) between 2007 and 2015 (Curtin SC et al, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:816. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6630a6). As compared to boys, girls in this age group also died more commonly by suffocation (56% vs 40%) over firearms (22% vs 48%) and poisoning (13% vs 5%).

Suicide and social media

Although we don’t know for sure what’s behind the acute rise in suicide, one thing that has increased sharply since 2007 is teen use of social media and personal digital devices. Today, over 95% of American youth are connected to the internet, and 45% are online almost constantly (Pew Research Center, May 2018).

Use of social media may be especially problematic for children and teens. Unlike teen interactions at school, the time spent on social media can be potentially limitless—inviting endless possibilities for stressors, ranging from cyberbullying to relationship breakups, at all hours of the day.

Girls might be especially vulnerable. Compared to boys, girls use social media more frequently and are more likely to experience cyberbullying. Social media use and cyberbullying is more strongly connected with depression in girls than boys. Furthermore, girls with depression elicit more negative responses from peers on social media than depressed boys do (Luby J and Kertz S, JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(5):e193916).

Assessment of imminent risk

Suicide risk assessment through clinical interview and mental status examination is vital for any psychiatric interview. There are many ways to screen for imminent risk. While we all might have our usual styles, there is a lot to be learned from the structure of evidence-based approaches. For example, the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) Toolkit, published by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), offers a simple four-question approach.

Other more extensive assessments such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) cover details of suicidal and self-injurious behavior, activating events, treatment history, current clinical status (ie, such things as current hopelessness, agitation, and historical details such as abuse), and protective factors such as reasons for living and family support. The even more detailed CAMS Suicide Status Form–4 (SSF-4) has a detailed assessment process including rating pain, comparing reasons for living and dying, and mental status and treatment planning for initial, interim, and final session stages of care. Even if you choose not to use one of these assessments, the structure of their approaches can help to organize your thinking and care planning.

Assessment of chronic risk

Chronic risk refers to the ongoing likelihood of the patient making a future suicide attempt. The most important chronic risk factors include prior or family history of suicide, history of maltreatment, access to firearms or other lethal methods, chronic physical or mental health disorder, substance use, and certain demographic variables (male gender, lack/loss of social support).

It is also important to assess for and address biopsychosocial risk factors. Mental health and well-being of parents and siblings can significantly affect teens’ depression and suicide risk. Treatment of maternal depression results in reduced externalization/internalization symptoms and reduced depression in children. I routinely recommend depression screening for children of mothers with depression and mothers of children with depression.

Ask Suicide-Screening Questions Toolkit Questionnaire

Source: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (www.tinyurl.com/y68bmngf)

Watchful outpatient management

Patients assessed to be at imminent risk of self-harm are usually referred to an emergency room or inpatient psychiatric units. Others are referred to intensive outpatient programs.

In less acute cases, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center has a Safety Plan Template that is a good starting point for developing a safety plan(see www.sprc.org/effective-prevention/strategic-planning). This plan involves a collaborative process of listening with intent, helping patients discover their triggers and how to address them. The plan also provides resources for patient and/or family help, such as 24-hour hotlines for phone, text, or chat as well as suggestions for making the environment safe. When dealing with a patient in crisis, remember the acronym LEAP: Listen, Empathize, Agree, and Partner. No-suicide contracts are no longer recommended due to lack of supporting evidence for their effectiveness.

For families with patients in outpatient programs, integrated CBT, DBT, mentalization, promotion of family resilience, family-based attachment therapy, and family CBT all show promise to address depression and suicide. While we recommend avoiding use of hypnotic medications and working to manage current medications to avoid interference with sleep, insomnia treatment via CBT-I (cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia) can improve depression and lessen suicidal ideation (Brent D, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;58(1):25–35).

While under your care, avoid prescribing medications that can be lethal in overdose, such as TCAs, benzos, and barbiturates. If you do, provide only a short supply at one time and ask pharmacists for blister packs when available.

Although restriction at home can be challenging, families need to take measures to make the environment as safe as possible (see Safety Plan Template link in earlier discussion). For example, make sure families are aware that commonly available objects (eg, extension cords, bedding, dog leashes) and anchor points (tree branches, beams, and closets) are often used for suicide by asphyxiation (Yau et al, Inj Epidemiol 2018;5(1):1). Although often considered only as a safety measure for young children, a useful protective measure is utilizing safes and lockboxes for prescriptions and OTC meds, and a locking cabinet for poisons, pesticides, cords, ropes, and knives.

Prevention

With teen suicide a chronic and growing concern, we need to focus on preventive strategies targeting vulnerable population at several levels, often in our roles consulting and collaborating beyond patient-focused appointments.

Family/home

We know that starting as early as possible is the best way to build resilience. Early intervention can be crucial. Parent training interventions like Positive Parenting Program (www.triplep.net/glo-en/home/) and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (www.pcit.org/) improve parenting skills and reduce child maltreatment, thus reducing potential risk factors. Family-based interventions such as Familias Unidas, Family Check-Up, and the Family Bereavement Program also improve long-term outcomes on suicide (Brent DA, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;58(1):25–35).

Limiting firearm access is critical. Whether your patient is at risk or not, always ask if there are firearms at home. Almost 30% of youth live in homes in which firearms are not stored safely, and of these, 40% of youth have easy access to such firearms. When firearms are kept locked, unloaded, and away from separately locked ammunition, children and teens are less likely to use them to harm not only themselves but others (Grossman DC et al, JAMA 2005;293(6):707–714). We strongly recommend that firearms be stored off-site or in firearm safes. If you want to ensure no access, ask the family to call law enforcement to remove the firearms from the house, and be sure to follow up with the family to check whether this has been done.

Hospitals

Emergency rooms can play an important role in suicide prevention. The ED-SAFE study showed that simple universal screening using the Patient Safety Screener-3 (see www.tinyurl.com/yxkehx42) and brief intervention led to lower suicide attempts at follow-up (Miller IW et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(6):563–570). Hospitals and correctional facilities should actively seek and restrict access to means and anchor points for hanging.

At the institutional scale, the Zero Suicide Initiative has had tremendous success across the UK and later in the US at Henry Ford Health System. The initiative’s efforts showed that suicide rates drop significantly when healthcare institutions (hospitals, clinics, etc.) provide suicide risk training to all staff, have the option of a dual-diagnosis unit, use rating scales to help assess depression, ensure adequate dosing of antidepressants, counsel family involvement in treatment, teach emotional regulation and distress tolerance to teens, and routinely conduct multidisciplinary review whenever a suicide in care takes place. (The Zero Suicide Guidelines are available at www.tinyurl.com/y3drvssn.)

School/community

At the school level, one notable prevention program is the Good Behavior Game, a pro-social classroom behavior management tool that teachers implement in the classroom (www.tinyurl.com/y5qf6pny). The goals of using this tool include reducing disruptive, aggressive, and/or socially isolating behaviors—risk factors for future problems ranging from suicidal thoughts and behaviors to substance use. First graders who participated regularly in this game showed persistent reductions in substance use, antisocial behavior, and suicidal thoughts even 25 years later. Among preventive programs, this has the best return on investment (Kellam SG et al, Addict Sci Clin Pract 2011;6(1):73–84).

In the community, bridge barriers with phones can be lifesaving, particularly at places where people frequently leap to their deaths.

CCPR Verdict: Preventing and treating suicide in teens is an uphill battle with worsening trends. Astute clinicians need to stay abreast of all the resources available in their area as well as online to afford the best chance of survival for their patients. If possible, try to bring some of the abovementioned measures/initiatives in your practice, neighborhood, school, or healthcare facility. Lastly, don’t go it alone. While it is always a good idea to have consultative relationships with colleagues to discuss difficult cases, in the matter of suicidality, it is extremely important to actively consult with other colleagues to better think through care plans and help ensure the best possible care in these hazardous circumstances.

Editor’s note: The topic of suicide runs broad and deep. Cultural issues, the black box warning of 2004 (see CCPR, Summer 2019), supervision of youths, and safety measures (www.tinyurl.com/y3o3nppa) are additional issues to consider.

Child PsychiatryRising trends

Although suicide rates fell in the 1990s, they started rising in 2007. The rate of suicide and preferred method differs by age.

10–14 years old: Between 2007 and 2015, the suicide rate increased slightly in boys (from 2.3 to 2.5 per 100k) but tripled in girls (from 0.6 to 1.7 per 100k). While death by suffocation and firearms was almost equal in boys (48% each), 70% of girls died by suffocation (Hedegaard H et al, NCHS Data Brief 2018;309:1–8).

15–19 years old: The suicide rate increased 31% for boys (from 10.8 to 14.2 per 100k) and more than doubled for girls (from 2.4 to 5.1 per 100k) between 2007 and 2015 (Curtin SC et al, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:816. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6630a6). As compared to boys, girls in this age group also died more commonly by suffocation (56% vs 40%) over firearms (22% vs 48%) and poisoning (13% vs 5%).

Suicide and social media

Although we don’t know for sure what’s behind the acute rise in suicide, one thing that has increased sharply since 2007 is teen use of social media and personal digital devices. Today, over 95% of American youth are connected to the internet, and 45% are online almost constantly (Pew Research Center, May 2018).

Use of social media may be especially problematic for children and teens. Unlike teen interactions at school, the time spent on social media can be potentially limitless—inviting endless possibilities for stressors, ranging from cyberbullying to relationship breakups, at all hours of the day.

Girls might be especially vulnerable. Compared to boys, girls use social media more frequently and are more likely to experience cyberbullying. Social media use and cyberbullying is more strongly connected with depression in girls than boys. Furthermore, girls with depression elicit more negative responses from peers on social media than depressed boys do (Luby J and Kertz S, JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(5):e193916).

Assessment of imminent risk

Suicide risk assessment through clinical interview and mental status examination is vital for any psychiatric interview. There are many ways to screen for imminent risk. While we all might have our usual styles, there is a lot to be learned from the structure of evidence-based approaches. For example, the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) Toolkit, published by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), offers a simple four-question approach.

Other more extensive assessments such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) cover details of suicidal and self-injurious behavior, activating events, treatment history, current clinical status (ie, such things as current hopelessness, agitation, and historical details such as abuse), and protective factors such as reasons for living and family support. The even more detailed CAMS Suicide Status Form–4 (SSF-4) has a detailed assessment process including rating pain, comparing reasons for living and dying, and mental status and treatment planning for initial, interim, and final session stages of care. Even if you choose not to use one of these assessments, the structure of their approaches can help to organize your thinking and care planning.

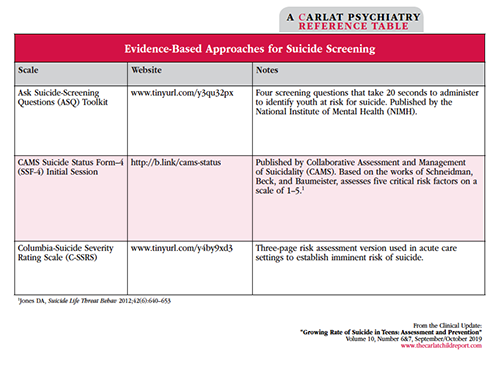

Table: Evidence-Based Approaches for Suicide Screening

Click to view full-size PDF.

Assessment of chronic risk

Chronic risk refers to the ongoing likelihood of the patient making a future suicide attempt. The most important chronic risk factors include prior or family history of suicide, history of maltreatment, access to firearms or other lethal methods, chronic physical or mental health disorder, substance use, and certain demographic variables (male gender, lack/loss of social support).

It is also important to assess for and address biopsychosocial risk factors. Mental health and well-being of parents and siblings can significantly affect teens’ depression and suicide risk. Treatment of maternal depression results in reduced externalization/internalization symptoms and reduced depression in children. I routinely recommend depression screening for children of mothers with depression and mothers of children with depression.

Ask Suicide-Screening Questions Toolkit Questionnaire

- In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?

- In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?

- In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?

- Have you ever tried to kill yourself? (If yes, ask how and when.)

- *If the patient answers yes to any of the above, ask: Are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now? If yes, please describe.

Source: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (www.tinyurl.com/y68bmngf)

Watchful outpatient management

Patients assessed to be at imminent risk of self-harm are usually referred to an emergency room or inpatient psychiatric units. Others are referred to intensive outpatient programs.

In less acute cases, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center has a Safety Plan Template that is a good starting point for developing a safety plan(see www.sprc.org/effective-prevention/strategic-planning). This plan involves a collaborative process of listening with intent, helping patients discover their triggers and how to address them. The plan also provides resources for patient and/or family help, such as 24-hour hotlines for phone, text, or chat as well as suggestions for making the environment safe. When dealing with a patient in crisis, remember the acronym LEAP: Listen, Empathize, Agree, and Partner. No-suicide contracts are no longer recommended due to lack of supporting evidence for their effectiveness.

For families with patients in outpatient programs, integrated CBT, DBT, mentalization, promotion of family resilience, family-based attachment therapy, and family CBT all show promise to address depression and suicide. While we recommend avoiding use of hypnotic medications and working to manage current medications to avoid interference with sleep, insomnia treatment via CBT-I (cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia) can improve depression and lessen suicidal ideation (Brent D, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;58(1):25–35).

While under your care, avoid prescribing medications that can be lethal in overdose, such as TCAs, benzos, and barbiturates. If you do, provide only a short supply at one time and ask pharmacists for blister packs when available.

Although restriction at home can be challenging, families need to take measures to make the environment as safe as possible (see Safety Plan Template link in earlier discussion). For example, make sure families are aware that commonly available objects (eg, extension cords, bedding, dog leashes) and anchor points (tree branches, beams, and closets) are often used for suicide by asphyxiation (Yau et al, Inj Epidemiol 2018;5(1):1). Although often considered only as a safety measure for young children, a useful protective measure is utilizing safes and lockboxes for prescriptions and OTC meds, and a locking cabinet for poisons, pesticides, cords, ropes, and knives.

Prevention

With teen suicide a chronic and growing concern, we need to focus on preventive strategies targeting vulnerable population at several levels, often in our roles consulting and collaborating beyond patient-focused appointments.

Family/home

We know that starting as early as possible is the best way to build resilience. Early intervention can be crucial. Parent training interventions like Positive Parenting Program (www.triplep.net/glo-en/home/) and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (www.pcit.org/) improve parenting skills and reduce child maltreatment, thus reducing potential risk factors. Family-based interventions such as Familias Unidas, Family Check-Up, and the Family Bereavement Program also improve long-term outcomes on suicide (Brent DA, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;58(1):25–35).

Limiting firearm access is critical. Whether your patient is at risk or not, always ask if there are firearms at home. Almost 30% of youth live in homes in which firearms are not stored safely, and of these, 40% of youth have easy access to such firearms. When firearms are kept locked, unloaded, and away from separately locked ammunition, children and teens are less likely to use them to harm not only themselves but others (Grossman DC et al, JAMA 2005;293(6):707–714). We strongly recommend that firearms be stored off-site or in firearm safes. If you want to ensure no access, ask the family to call law enforcement to remove the firearms from the house, and be sure to follow up with the family to check whether this has been done.

Hospitals

Emergency rooms can play an important role in suicide prevention. The ED-SAFE study showed that simple universal screening using the Patient Safety Screener-3 (see www.tinyurl.com/yxkehx42) and brief intervention led to lower suicide attempts at follow-up (Miller IW et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(6):563–570). Hospitals and correctional facilities should actively seek and restrict access to means and anchor points for hanging.

At the institutional scale, the Zero Suicide Initiative has had tremendous success across the UK and later in the US at Henry Ford Health System. The initiative’s efforts showed that suicide rates drop significantly when healthcare institutions (hospitals, clinics, etc.) provide suicide risk training to all staff, have the option of a dual-diagnosis unit, use rating scales to help assess depression, ensure adequate dosing of antidepressants, counsel family involvement in treatment, teach emotional regulation and distress tolerance to teens, and routinely conduct multidisciplinary review whenever a suicide in care takes place. (The Zero Suicide Guidelines are available at www.tinyurl.com/y3drvssn.)

School/community

At the school level, one notable prevention program is the Good Behavior Game, a pro-social classroom behavior management tool that teachers implement in the classroom (www.tinyurl.com/y5qf6pny). The goals of using this tool include reducing disruptive, aggressive, and/or socially isolating behaviors—risk factors for future problems ranging from suicidal thoughts and behaviors to substance use. First graders who participated regularly in this game showed persistent reductions in substance use, antisocial behavior, and suicidal thoughts even 25 years later. Among preventive programs, this has the best return on investment (Kellam SG et al, Addict Sci Clin Pract 2011;6(1):73–84).

In the community, bridge barriers with phones can be lifesaving, particularly at places where people frequently leap to their deaths.

CCPR Verdict: Preventing and treating suicide in teens is an uphill battle with worsening trends. Astute clinicians need to stay abreast of all the resources available in their area as well as online to afford the best chance of survival for their patients. If possible, try to bring some of the abovementioned measures/initiatives in your practice, neighborhood, school, or healthcare facility. Lastly, don’t go it alone. While it is always a good idea to have consultative relationships with colleagues to discuss difficult cases, in the matter of suicidality, it is extremely important to actively consult with other colleagues to better think through care plans and help ensure the best possible care in these hazardous circumstances.

Editor’s note: The topic of suicide runs broad and deep. Cultural issues, the black box warning of 2004 (see CCPR, Summer 2019), supervision of youths, and safety measures (www.tinyurl.com/y3o3nppa) are additional issues to consider.

Issue Date: October 3, 2019

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)