Learning objectives

After this webinar, clinicians should:

- Describe how to use motivational interviewing to reduce marijuana use in youth.

- Summarize the technique of weighing advantages and disadvantages of a potentially problematic habit or behavior.

- Differentiate when motivational interviewing is more likely to be effective to reduce marijuana use.

- Explain how to balance recommendations to change harmful behaviors with respecting the autonomy and agency of children and adolescents.

[Transcript edited for clarity]

This is Motivational Interviewing for Teens, Focus on Marijuana, a Carlat webinar. I'm Dr. Josh Feder, Editor-in-Chief at the Carlat Child Psychiatry Report. I have no conflicts or disclosures to report for this activity. Our learning objectives after the webinar: clinicians should, number one, describe how to use motivational interviewing to reduce marijuana use in youth. Number two, summarize the technique of weighing the advantages and disadvantages of a potentially problematic habit or behavior. Number three, differentiate when motivational interviewing is more likely to be effective in reducing marijuana use. And number four, explain how to balance recommendations to change harmful behaviors while respecting the autonomy and agency of children and adolescents.

Marijuana Impact

Key points

- Teens have more problems from marijuana than alcohol—academically, with mental health, and with delinquency.

- Teens who use cannabis frequently are more likely to do poorly on memory tests and higher-level problem-solving and information processing.

- Psychosis rates double with marijuana use

Teens have more problems from marijuana than alcohol, academically, with mental health, and with delinquency. Rates of cannabis use disorder have been found to be three times as high as for alcohol use disorder. Teens who use cannabis frequently are more likely to do poorly on memory tests and high-level problem-solving and information processing. And psychosis rates double with marijuana use.

Screening: CRAFFT Captures Alcohol/Cannabis Use

There's a useful screening tool for substance use that captures alcohol and cannabis use in teens. It's called the CRAFFT.

C. Have you ever ridden in a car driven by someone, including yourself, who was high or had been using alcohol or drugs?

R. Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to relax, feel better about yourself, or fit in?

A. Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself, alone?

F. Do you ever forget things you did while using alcohol or drugs?

F. Do your family or friends ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use?

T. Have you gotten into trouble while you were using alcohol or drugs?

Two or more yes answers indicate the need for further assessment.

What Is Motivational Interviewing?

Well, what is motivational interviewing? It's a collaborative approach to help teens make healthy choices if they are ready. It helps them to think through the pros and cons of using the substance. Does it make sense to the teen to change their behavior?

How To Do Motivational Interviewing

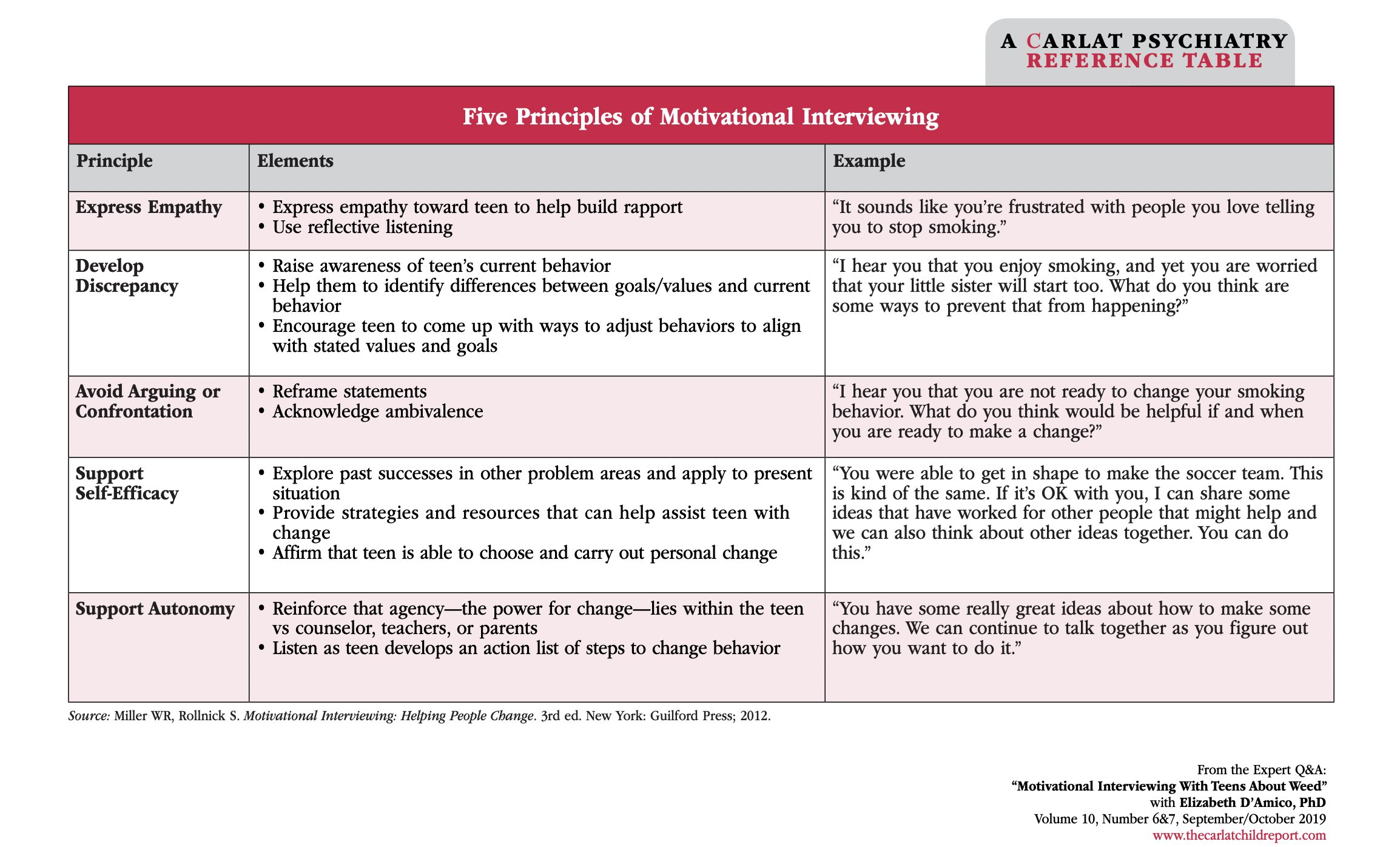

There are five principles of motivational interviewing, and I want to go through them one by one to talk about the elements and give you some sample language you might use with the kids and teens who you work with.

Empathy

The first principle is to express empathy. Express empathy toward the teen to help build rapport and use reflective listening. For example, “It sounds like you're frustrated with people you love telling you to stop smoking.”

Develop discrepancy

The next one is to develop discrepancy. Raise awareness of the teen's current behavior. Help them to identify differences between their goals and values and their current behavior. And encourage the teen to come up with ways to adjust their behaviors. to align with their own stated values and goals. For example, “I hear that you enjoy smoking, and yet you're worried that your little sister will start smoking, too. What do you think are some ways to prevent that from happening?”

Avoid arguing

The next principle is to avoid arguing or confrontation with the person. Reframe statements and acknowledge ambivalence. For instance, you might say, “I hear that you are not ready to change your smoking behavior. What do you think would be helpful if and when you are ready to make a change?”

Self-efficacy

The next principle is to support self-efficacy. Explore past successes in other problem areas and apply that to the present situation. Provide strategies and resources that can help assist the team with change. And affirm that the teen can choose and carry out personal change. For example, you might say something like, “You were able to get in shape to make the soccer team.”

This is kind of the same. “If it's okay with you, I can share some ideas that have worked for other people that might help and we can also think about other ideas together. You can do this.”

Autonomy

The final principle that we talk about is to support the autonomy of the teen. Reinforce that their agency, the power for change, lies within the teen versus lying within outside people like counselors or teachers or parents.

And listen as the teen develops an action list of steps to change their behavior. You might say something like, “You have some great ideas about how to make some changes. We can continue to talk together as you figure out how you want to do it.”

Resistance to Change

Key points

- Wanting to be with friends/FOMO: “How confident are you to not use around your friends on Friday, since you said you wanted to cut back on your use?”

- Wanting to feel better: “How confident are you to try other ways to get to sleep without using?”

- If they’re ready to make a change, we discuss how they could make that happen.

Well, what about resistance to change? A lot of teens want to be with their friends. They have FOMO, fear of missing out. You might ask, how confident are you to not use around your friends on Friday since you said you wanted to cut back on your use?

Another reason kids will often be using substances, and in particular marijuana, is to feel better. You might ask, “How confident are you to try other ways to feel better or get to sleep without using marijuana?”

If they're ready to make a change, we discuss how they could make that happen.

Six Stages of Change

We're going to talk about six stages of change. Precontemplation, contemplation, planning, action, maintenance, and relapse. And we're going to do it using case vignettes.

Case Example: Precontemplation

For precontemplation, here's a kid who was depressed and anxious—on the autism spectrum—who smokes weed daily to relax. That's her sitting with her face in her hands, and me taking notes and trying to work with her. She wasn't ready to change, but she really couldn't function.

Think about this for a minute. With somebody like this, what would you say? I'm going to give you 10 or 20 seconds to think about it, and maybe to jot some things down that you might say.

Are Teens Receptive to MI?

Not easy. Is it? Are teens receptive to motivational interviewing? Well, many are willing to talk about it. This kid was. Many want to make changes. This kid wasn't ready though. You need to talk about what it would mean if they continued to use, and this works well when they are ambivalent. For instance, you might say something like:

- “I can see that it's fun for you to use and you'll love hanging out with your friends and yet you've gotten in a lot of trouble with your parents and your grades are dropping.”

That doesn't apply to this other patient I was talking about who's more depressed. In her case, I might say something like:

- “You're using and you're doing it to feel better, and yet, you seem pretty stuck.”

Case Example: Contemplation

What about contemplation? Here's a kid, you can see him with a friend over here on the left-hand side of the screen, they're watching TV, they're smoking weed, they've got a bunch of beers they've been drinking. This teen was socially anxious, had a history of a head injury, and was smoking daily to get to sleep. He was drinking daily alone or with others. He was no longer attending school but recently had cut down a bit again, for the umpteenth time. What might you say to this teen? And again, I'm going to give you some time to think about it.

Harm Reduction Is Good

Key points:

- Treatment ensures ongoing commitment rather than immediate cessation.

- Progress from daily to once-a-week usage is positive.

- Potential avoidance of impaired driving or being passengers.

- Improved academic performance by refraining during school hours.

- Continued social engagement while reducing use, especially on Fridays.

- Reduced negative consequences from substance use.

Harm reduction is good. Teens aren't going to walk out of the office and never use again. Cutting back to once a week versus every day is a great outcome in itself. Teens might avoid using and driving or riding with a driver who's using. They might stop using during school hours and get more homework done.

They might still use it with their friends on Friday, but the consequences are reduced. You have to go with what your patient thinks they can handle as a starting point.

What Do You Tell Parents?

What do you tell parents? Parents who expect that you're going to help their kid be abstinent are going to be disappointed. Brief motivational interviewing is to help teens change their use early in the process. Teens do better with resources like websites and phone numbers that might help them think about this, to contemplate the possibility of stopping use. If they have more bad things happening, motivational interviewing is more effective. However, if a teen is using heavily, they need more intensive treatment.

Case Example: Planning

The next stage is planning— when somebody is beginning to think about how they would actually reduce or stop their use. Here we have a late teen or young adult who's socially anxious and had a history of loss in their family. They were smoking daily to sleep—that's a common theme that people say that they're using to sleep.

They were drinking daily, alone, or at times with others. They had successfully reduced alcohol and had switched from growing weed to growing other things like lettuce. And they were changing their work and exercise habits to support the change. What might you say to this person?

The Process of MI Over Several Appointments

Key points

- Motivational interviewing typically spans multiple appointments.

- "All you need is 15 minutes" is the tagline, with research backing its efficacy in primary care.

- Consider readiness and confidence for change.

- Build coping skills for motivation.

- Emphasize harm reduction for those with consequences but low motivation to quit

The process of motivational interviewing often occurs over several appointments. The tagline is’ “All you need is 15 minutes.” There is some research showing that in a primary care office, 15 minutes spent on motivational interviewing can lead to markedly, significantly reduced use when we check in a year later. That's impressive.

But a lot of times, especially with our patients in the mental health system, you might not have changed. And it's important to think about, well, why not? Maybe the person's ready to make changes now when they weren't before. Are they motivated to change, but maybe they're not confident that they could: “I'd like to change, but I don't think I can do it.”

In that case, you need to work on their coping skills. And the things that they do to take care of themselves and to manage stress and everyday life. If they're not motivated, but confident—think about that. I'm sure you've had these kids who might say: “I could quit anytime I wanted. I just like using and I don't want to quit.”

Well, that's true for so many people who use substances on an ad hoc basis just to kind of feel better. Those people, some of them, don't become our patients, at least from that standpoint, because it's not interfering enough for it to come to our attention.

But for those for whom there are consequences to their using, even though they don't feel like stopping, that's when we talk more about emphasizing harm reduction plans so that it's not getting in the way. They might say, “I could quit. anytime I want.” And you might be talking about, “Okay, it seems like when you're using during the day, it's interfering with your schoolwork. And you say you also want to go to college. So maybe we can talk about how you might shift your use during the school day so that maybe you could. Bring your grades up so you can get where you want to go.”

Case Example: Action

Well, at some point people sometimes take action. We like to think that'll happen after we've met with them a few times. Here's a kid who is an athlete, has some social communication differences, and would smoke weed daily to relax, but doesn't drink. His girlfriend didn't like smoking, which was helpful, and he had successfully stopped weed for two months while working out more regularly.

Think about what you would say to this person to continue to encourage them without creating a situation in which you're stealing their internal agency by saying, “good job” or “attaboy.” It's tricky. Think about it for a few seconds.

Have you thought about it? It's a little bit hard, and while this isn't a webinar on punishment through rewards, Alfie Cohen's work, it's important to remember that if you replace a person's internal, intrinsic motivation with external rewards and punishments, typically they become more dependent on the externals and a lot less likely to change their behavior.

So you want to figure out how to embrace the action and ask them how they feel about it. You’re emphasizing their own experience, self-efficacy, and confidence in their competence to make these changes for themselves.

Case Example: Maintenance

Key points

- Focus on long-term maintenance after stopping substance use.

- Reduction of substance use over time improves resilience.

- Transitioning from school to workplace is common, requiring ongoing support.

- Coping skills like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, exercise, and stress management are crucial for relapse prevention.

Well, once someone has stopped using, then we're talking about maintenance—staying away from it over the long haul, even during difficult times when they might be tempted to go back to using. Here's a person who is depressed and anxious, socially different. Well, that's my practice. A lot of the people are socially different. Maybe that's yours too.

This person used weed and alcohol for years, which frankly increased their resistance to any kind of changes and made them more reactive to stressful situations. So it got in the way. But over time, actually over the course of a couple of years, they were able to reduce their use, and then had stopped alcohol use two years ago, and then weed one year ago.

At this point, they're transitioning from school to the workplace, and they're working in tech. Well, that happens with a lot of our people. If you see kids in adolescence, a lot of us follow our patients into adulthood. They're working in tech, and when they're not using, we're finding that they're more resilient over time.

But they still need support. When those difficult moments come up, they're reacting in a way where they're craving the use again, and maybe wanting to go back to it. What would you say to this person?

You're probably thinking about coping skills and how we manage stress. Are they able to manage their sleep better? We've talked in The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report about how regular sleep hygiene recommendations don't make much of a change for people because they usually don't make those changes or it's more complicated.

However, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia—which you can learn to do in the office, even as a prescriber—can be really helpful. So not just telling people not to lie awake in bed at night, but problem-solving if that's what they're doing, what else they could be doing, and thinking about how they could change their habits. That's just one example of a coping skill.

Other things include trying to encourage people to do more exercise and exploring the barriers to physical exercise, which could also be used for coping with stresses that might increase their likelihood of relapse. And then, of course, there are other techniques that we can use for stress management, including deep breathing techniques, meditation techniques, and cognitive behavioral therapies but also insight-oriented therapies as well.

I do therapy in my practice. You may or may not do that or have time for it, but I have to say that even in relatively briefer interactions when people are coming in to think about medication and other life problems that are on your list, you can do some of this with them.

Maintaining Maintenance

We're trying to build self-efficacy for the future. So, while someone is staying clean, that's the time to ask them, “Well, if you were having problems, how would you manage them? What would you do? Let's think about those times when inevitably, you're going to be under stress, work deadlines, and relationship problems. Who are the people in your life who can support you and help you out?”

And talk about strategies to recognize problems so that the person knows when a change is going to be needed. For instance, if work is piling up, if they've taken on too many courses at college or in high school, too many AP courses, or if they're working and they're taking on more and more work, or in their relationships, if they're having trouble with multiple people in their lives—how can they recognize that it's becoming overwhelming before it does overwhelm them? And what strategies might they be using to try to step aside from some of the stress, to manage it, to get additional assistance as needed?

Case Example: Relapse

The last stage, unfortunately, is relapse. Here's a person who has ADHD. They're anxious, they're depressed, and they're on the autism spectrum. They spent a lot of their life using and then were able to stop for a couple of years with therapy, family support, and medication for anxiety.

But now, what's happened? They were working in cubicle form. But now they're not at work. They're at home. They're sitting on their bed. They're cruising the internet on their laptop. They're back to using. They've left aside their medication and they're sporadic with their therapy. They're not working. They say they're “working on their career from home.”

What would you say to a person in this kind of circumstance?

It's a real challenge. You don't want to be browbeating the person. But boy, that just makes your heart sink when you have these kinds of situations. And I know people listening have had those kinds of things happen. Makes you wonder what it was about the cubicle farm that didn't work out. What is it about certain work situations that just aren't a good fit or a good long-term fit for people? How do you help them to be more resilient or how to find places where they might be productive but not in a way that has such a high cost to that person in terms of their mental health?

When to Consider Using MI

There are a number of things that we want to consider when using motivational interviewing. Certainly, substance use is one place where we use motivational interviewing, and we've described the stages of use and how motivational interviewing might apply. But you can also use motivational interviewing in other circumstances. Like when you're managing electronic use, which often has an addictive quality to it. There’s certainly been a lot written in the past 20 years or so about internet addictions and electronics addictions.

Well, the stages are not different: precontemplation, contemplation, planning, action, maintenance, and relapse. Of course, not unlike eating, most of us have to have some interaction with electronics. So, you can't be abstinent from electronic use. Therefore, you need to be more differentiated in how you think about what kinds of electronic use you're trying to manage. Similarly, we talked a little bit earlier about managing sleep and bedtime, maybe using cognitive behavioral intervention for insomnia, but motivational interviewing can also be used for managing sleep.

Think about it this way. A lot of people get activated at nighttime, right? They stay up very late. Why is that? Well, it's a quieter time, perhaps. Maybe it's associated with electronics use. But even in other kinds of projects, some people stay up just doing things at night. Is that something that they're built to do?

Well, remember, adolescents are often people who stay up late and sleep in. Younger kids tend to wake up earlier, go to bed earlier, and adults tend to wake up earlier and go to bed earlier. There may be something about our heritage as a species that might make it advantageous for adolescents to tend to be up. But some people do that to a degree that is not very good for them, and they seem to get a physiological boost from it that is not unlike what other people might be experiencing when they're using electronics and/or substances. So think about motivational interviewing as a technique you could be using. Think about the advantages and disadvantages when you're trying to manage bedtime.

School attendance and homework are other, areas where you might also think about the advantages and disadvantages. Think about precontemplation and contemplation and planning and then get an active plan and then maintain. And you get a lot of relapses with people falling off about attending school and doing homework. There are also issues of social anxiety and school avoidance to think about there.

And then finally, in the area of sexual activity, safe sex is another area where we want to manage that momentary impulsivity that some people have in their sexual activity. And we can use similar techniques of motivational interviewing to try to address that set of problems as well.

When to Refer for More Intensive Treatment

Well, not everybody's going to respond to motivational interviewing. We need to think about when to refer for more intensive treatment. If a person is using substances or engaging in the behavior that's problematic every day—not going to school, having way too many problems to manage by asking a little bit about advantages and disadvantages and trying to do harm reduction—then you need to be thinking about whether they need something beyond outpatient motivational interviewing, but maybe intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospital treatment, or even for some people, residential treatment.

Another thing to think about is that if teens are not experiencing consequences, they may not be ready to change. Lots of kids are using and we're worried about them, but they're doing okay at school or with their peers. They're not having trouble with their families per se, other than the fact that people don't want them to use. There just isn't any internal motivation that we can work on, that we can work with. There are no discrepancies between their aspirations and their use.

Navigating Uncertainty

There is a lot of uncertainty. Keep in mind the ethical balance between our medical paternalism and the patient's autonomy. If we become people who are just dictating to them, that makes us external motivators, and that just reduces the likelihood that they will ever change.

We need to stay humble ourselves to avoid burnout. You win some and you lose some with substance use and with other kinds of behaviors. But you do win some, and that should keep us going in the long run.

Resources for Clinicians

Here are some resources for clinicians:

- Training for motivational interviewing to reduce marijuana use with children and adolescents.

- Online training for providers put out by the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

- And there's that CRAFFT questionnaire, which you can also get for free.

References:

- Online training for providers: National Institute of Drug Abuse (http://training.simmersion.com/).

- CRAFFT: https://tinyurl.com/3cwpxr69

- Shenoi RP, Pediatrics 2019;144(2):e20183415

- D’Amico EJ et al, Addiction 2016;111(10):1825–1835

- D’Amico EJ et al, Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20161717

- Morin JFG et al, Am J Psychiatry 2018;176(2):98–106

Earn CME for watching our webinars with a Webinar CME Subscription.

__________

The Carlat CME Institute is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Carlat CME Institute maintains responsibility for this program and its content. Carlat CME Institute designates this enduring material educational activity for a maximum of one half (.5) AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM. Physicians or psychologists should claim credit commensurate only with the extent of their participation in the activity.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)