Home » Maintenance of Certification: What You Need to Know

Maintenance of Certification: What You Need to Know

September 1, 2014

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Daniel Carlat, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Publisher, The Carlat Report.

Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

Hello again, dear readers. I’m back from Washington, where I spent the last two and a half years working on health policy for the Pew Charitable Trusts. And while maintenance of certification (MOC) is not inherently the most scintillating of topics to inaugurate my return, it means a lot for me because I’m up for recertification myself in 2018 and I very much needed to learn the new process.

Since I last wrote about MOC in 2010, the most relevant news has not been within the program itself, but in the increasingly rancorous reaction against its requirements from physicians of all specialties (see for example, http://bit.ly/1gh77zp).

To give you a taste of how dimly some psychiatrists are viewing it, you can read an op-ed piece we’ve published on our website (Maintenance of Certification (MOC)—Is it safe to opt out?). Regardless, it doesn’t look like ABPN is going to be ditching MOC any time soon, so this article pretty much lays out what you have to do, without (much) editorializing.

MOC Then…

I graduated residency in 1995, and became board certified in 1998. All I had to do was to take a long and not very hard multiple choice exam. Ten years later, I took the 2008 version of the exam (still easy, and this is not me bragging—the exam’s pass rate is 99%), and if nothing had changed, I wouldn’t need to do anything other than take these exams every 10 years for the rest of my clinical life. ABPN changed this system because, let’s face it, clicking the right multiple choice bubbles on a computer screen is not the most reassuring evidence that a psychiatrist is still competent.

(By the way, if you are lucky enough to have first been certified in 1994 or earlier, you can ignore this article—you are grandfathered into the current every-decade exam schedule for the rest of your professional life).

And Now: Three Years is the New Ten

First of all, wrap your mind around this: three years is the new 10 years. That’s right, the new MOC process chunks your requirements—most of them anyway—into three year periods instead of 10 years…except for the written test—that’s still done every 10 years.

One big exception is if you were certified or recertified before 2012—then you are in a 10 year cycle until your next certification. (This is too involved to delve into here, please see http://bit.ly/1wbobOB for more explanation.)

There are four overall requirements of the brave new world of board certification.

I. Maintain your medical license. This one’s fairly easy—as long as you stay out of trouble, earn enough CME credits, maintain malpractice insurance, and are willing to shell out $600 every two years (that’s the fee in Massachusetts, however, the fee and requirements vary from state-to-state)—you can maintain your license.

II. Earn lots of CME—including the new fancy expensive kind. Most states already require a minimum number of category 1 CME in order to maintain your medical license, varying from 10 to 25 per year. The MOC program has upped the ante, requiring an average of 90 CMEs per three years (an average of 30 per year). In addition, 24 of those 90 credits (average eight per year) have to be super CMEs, the so-called “self-assessment” (SA) credits.

The only difference between regular credits and SA credits is that SA CME includes an excruciating number of pre-and post-test questions, some recommendations for extra reading, and software that can compare your pre-test answers with those of your peers. All this extra material has to be developed by someone, which takes extra time and money—clearly a sore point for those who have to do the paying.

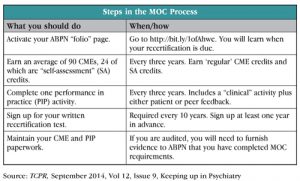

There’s a lot of moving parts to MOC, and we still haven’t gotten to the dreaded performance in practice (PIP) yet. How do you figure out exactly what you need to do when? It’s surprisingly easy—go to the ABPN website [http://bit.ly/1ofAhwe], and log on to your own personalized “folio” page. You’ll have to activate your account first, and then you’ll get a neat snapshot of your professional persona, including your address, contact information, license numbers, etc. More to the point, you’ll find out what year your recertification is due (yep, I was right…2018 for me), and you’ll get a table laying out what needs to happen, what you’ve done, and how much you need to do.

My folio page told me that I have completed 50 of the 300 CME credits due by 2017, but none of the 24 SA credits due. I wasn’t crestfallen—I’ve actually done a lot more than 50 credits, but ABPN doesn’t know about it yet. I was happy to be told that I have to complete only 24 SA credits before 2017.

III. Take a test. You still have to take a test every 10 years. Incredibly, you have to sign up for the test a full year in advance. Don’t let that one slip off your to-do list.

IV. Performance in Practice. The idea behind PIP is that CME credits and exams aren’t good enough for demonstrating clinical abilities. You need more valid evidence, in the form of chart information, and evaluations from your patients or peers.

You have to complete one PIP activity every three years—which is a bit of a misnomer because “one” PIP includes two activities—a “clinical” activity plus your choice of two “feedback” activities—patient feedback or peer feedback.

Clinical Activities. The clinical activity involves choosing at least five charts and collecting data about how well you are following practice guidelines. Are you asking all your depressed patients about suicidality at each visit? Are you weighing patients who are taking antipsychotics? It’s up to you to choose which guidelines to focus on, and then to assess your performance in order to develop a plan for improving your practice. After at least six months, you are then required to choose five different patient charts to see if you’ve changed your ways (or have just improved your documentation).

While theoretically you could do all this on your own, ABPN essentially requires that you do your clinical activity through one of their “approved” products, which are listed online (see bit.ly/1tnCwTn). You have two options here—you can either pay money for a product that is independent of pharmaceutical companies, or you can pay nothing for an industry-funded product. If it seems distressing that ABPN would officially approve educational activities funded by companies that stand to profit from the “Performances in Practice” being taught, you’re not alone!

Feedback Activities. You can choose either five patients or five colleagues to fill out an evaluation of your professional skills. The forms are downloadable here: http://bit.ly/1ADeEws. Of course, this is unlikely to be a valid measure of one’s competence, since you are free to cherry pick the patients or colleagues who love you the best.

What to do with all your paperwork.

Just keep it all. You don’t have to furnish any evidence to ABPN that you’ve actually completed any MOC requirement, but you do have to tell them that you’ve done so. It’s on the honor system, though ABPN has said it will audit approximately 5% of psychiatrists to keep everyone on their toes.

TCPR’s Verdict: MOC certification appears to be a well-intentioned work in progress. We hope that ABPN takes the “in progress” part seriously.

General PsychiatrySince I last wrote about MOC in 2010, the most relevant news has not been within the program itself, but in the increasingly rancorous reaction against its requirements from physicians of all specialties (see for example, http://bit.ly/1gh77zp).

To give you a taste of how dimly some psychiatrists are viewing it, you can read an op-ed piece we’ve published on our website (Maintenance of Certification (MOC)—Is it safe to opt out?). Regardless, it doesn’t look like ABPN is going to be ditching MOC any time soon, so this article pretty much lays out what you have to do, without (much) editorializing.

MOC Then…

I graduated residency in 1995, and became board certified in 1998. All I had to do was to take a long and not very hard multiple choice exam. Ten years later, I took the 2008 version of the exam (still easy, and this is not me bragging—the exam’s pass rate is 99%), and if nothing had changed, I wouldn’t need to do anything other than take these exams every 10 years for the rest of my clinical life. ABPN changed this system because, let’s face it, clicking the right multiple choice bubbles on a computer screen is not the most reassuring evidence that a psychiatrist is still competent.

(By the way, if you are lucky enough to have first been certified in 1994 or earlier, you can ignore this article—you are grandfathered into the current every-decade exam schedule for the rest of your professional life).

And Now: Three Years is the New Ten

First of all, wrap your mind around this: three years is the new 10 years. That’s right, the new MOC process chunks your requirements—most of them anyway—into three year periods instead of 10 years…except for the written test—that’s still done every 10 years.

One big exception is if you were certified or recertified before 2012—then you are in a 10 year cycle until your next certification. (This is too involved to delve into here, please see http://bit.ly/1wbobOB for more explanation.)

There are four overall requirements of the brave new world of board certification.

I. Maintain your medical license. This one’s fairly easy—as long as you stay out of trouble, earn enough CME credits, maintain malpractice insurance, and are willing to shell out $600 every two years (that’s the fee in Massachusetts, however, the fee and requirements vary from state-to-state)—you can maintain your license.

II. Earn lots of CME—including the new fancy expensive kind. Most states already require a minimum number of category 1 CME in order to maintain your medical license, varying from 10 to 25 per year. The MOC program has upped the ante, requiring an average of 90 CMEs per three years (an average of 30 per year). In addition, 24 of those 90 credits (average eight per year) have to be super CMEs, the so-called “self-assessment” (SA) credits.

The only difference between regular credits and SA credits is that SA CME includes an excruciating number of pre-and post-test questions, some recommendations for extra reading, and software that can compare your pre-test answers with those of your peers. All this extra material has to be developed by someone, which takes extra time and money—clearly a sore point for those who have to do the paying.

There’s a lot of moving parts to MOC, and we still haven’t gotten to the dreaded performance in practice (PIP) yet. How do you figure out exactly what you need to do when? It’s surprisingly easy—go to the ABPN website [http://bit.ly/1ofAhwe], and log on to your own personalized “folio” page. You’ll have to activate your account first, and then you’ll get a neat snapshot of your professional persona, including your address, contact information, license numbers, etc. More to the point, you’ll find out what year your recertification is due (yep, I was right…2018 for me), and you’ll get a table laying out what needs to happen, what you’ve done, and how much you need to do.

My folio page told me that I have completed 50 of the 300 CME credits due by 2017, but none of the 24 SA credits due. I wasn’t crestfallen—I’ve actually done a lot more than 50 credits, but ABPN doesn’t know about it yet. I was happy to be told that I have to complete only 24 SA credits before 2017.

III. Take a test. You still have to take a test every 10 years. Incredibly, you have to sign up for the test a full year in advance. Don’t let that one slip off your to-do list.

IV. Performance in Practice. The idea behind PIP is that CME credits and exams aren’t good enough for demonstrating clinical abilities. You need more valid evidence, in the form of chart information, and evaluations from your patients or peers.

You have to complete one PIP activity every three years—which is a bit of a misnomer because “one” PIP includes two activities—a “clinical” activity plus your choice of two “feedback” activities—patient feedback or peer feedback.

Clinical Activities. The clinical activity involves choosing at least five charts and collecting data about how well you are following practice guidelines. Are you asking all your depressed patients about suicidality at each visit? Are you weighing patients who are taking antipsychotics? It’s up to you to choose which guidelines to focus on, and then to assess your performance in order to develop a plan for improving your practice. After at least six months, you are then required to choose five different patient charts to see if you’ve changed your ways (or have just improved your documentation).

While theoretically you could do all this on your own, ABPN essentially requires that you do your clinical activity through one of their “approved” products, which are listed online (see bit.ly/1tnCwTn). You have two options here—you can either pay money for a product that is independent of pharmaceutical companies, or you can pay nothing for an industry-funded product. If it seems distressing that ABPN would officially approve educational activities funded by companies that stand to profit from the “Performances in Practice” being taught, you’re not alone!

Feedback Activities. You can choose either five patients or five colleagues to fill out an evaluation of your professional skills. The forms are downloadable here: http://bit.ly/1ADeEws. Of course, this is unlikely to be a valid measure of one’s competence, since you are free to cherry pick the patients or colleagues who love you the best.

What to do with all your paperwork.

Just keep it all. You don’t have to furnish any evidence to ABPN that you’ve actually completed any MOC requirement, but you do have to tell them that you’ve done so. It’s on the honor system, though ABPN has said it will audit approximately 5% of psychiatrists to keep everyone on their toes.

TCPR’s Verdict: MOC certification appears to be a well-intentioned work in progress. We hope that ABPN takes the “in progress” part seriously.

KEYWORDS practice-tools-and-tips

Issue Date: September 1, 2014

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)