Home » Binge Eating Disorder: Should You Use Vyvanse?

Binge Eating Disorder: Should You Use Vyvanse?

June 1, 2015

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Talia Puzantian, PharmD, BCPP

Clinical psychopharmacology consultant in private practice, Los Angeles, CA. www.taliapuzantian.com

Dr. Puzantian has disclosed that she has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

Daniel Carlat, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Publisher, The Carlat Report.

Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

In January of this year, the FDA approved the stimulant lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) as the first drug with an indication for binge eating disorder (BED). Patients are hearing the buzz and may be asking you to prescribe it, but you may have some questions first. Is BED different from extreme overeating which plagues so many Americans? Is this just a stimulant being used for appetite suppression? What’s the evidence and what are the risks? Are there alternatives?

Amid some controversy, BED made its formal diagnostic debut in DSM 5 in 2013. For a diagnosis of BED, a patient has to have recurring episodes (at least once a week over three months) of binge eating, which means a time limited (DSM-5 suggests 2 hours) period of eating significantly more food than most people would consider normal, coupled with a sense of loss of control of eating. There are two main differences between BED and bulimia nervosa (BN): (1) Patients with BED don’t purge or exercise excessively to prevent weight gain; (2) They aren’t “inappropriately” concerned with body image or body shape.

Given the combination of binge eating and the lack of compensatory behaviors, you won’t be surprised to hear that patients with BED gain weight. In fact, estimates are that up to 90% of patients with BED are overweight to obese. Which brings up another issue—is BED just another term for overeating? This is a crucial distinction because being overweight or obese affects 69% of the US, whereas BED as strictly defined has a prevalence of about 2% in men and 3.5% in women (Hudson JI et al, Biol Psychiatry 2007;61(3):348–358). With Vyvanse now approved for BED, the concern is that it will be prescribed indiscriminately for overweight patients. Flashback to the 1960s, when “diet doctors” and weight loss clinics prescribed FDA-approved amphetamines for weight loss, fueling the amphetamine epidemic that led directly to Congress creating our current system of controlled substances (Rasmussen N, Am J Public Heath 2008;98(6):974–985, free full text online here).

We’ll go through the data on Vyvanse and briefly compare it with other potential treatments for BED, then give you some recommendations.

Vyvanse for BED: The Data

FDA approval was based on two Shire-sponsored, short term (12-week) studies with a total of 745 adults with moderate to severe BED (Citrome L Int J Clin Pract 2015;69(4):410–421). Patients were excluded if they had substance use disorders, ADHD, depression or anxiety—which might reduce the generalizability of the results for psychiatric practitioners, since we’re unlikely to be treating otherwise psychiatrically healthy binge eaters. Those patients will see their PCPs.

Patients enrolled in the studies were bingeing an average of about 5 days per week. Those randomized to receive 50 mg/day or 70 mg/day of Vyvanse reported a reduction of 3.9 bingeing days per week compared to a decrease of about 2.4 bingeing days per week with the placebo. Effect sizes for Vyvanse were large and ranged from 0.83–0.97. But on secondary measures assessing depression, anxiety and other psychiatric symptoms, Vyvanse did not beat placebo.

An earlier proof of concept study showed 30 mg/day was not more effective than placebo (McElroy SL et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(3):235–246), explaining the choice of doses for these studies. Patients on Vyvanse lost 6% of their body weight during the study—significantly more than patients on placebo who were essentially weight neutral.

The side effects more common with Vyvanse than placebo were dry mouth (36% vs 7%), insomnia (20% vs 8%), decreased appetite (8% vs 2%), increased heart rate (7% vs 1%), feeling jittery (6% vs 1%) and anxiety (5% vs 1%). Nonetheless, the rate of discontinuation from Vyvanse was low, ranging from 1.5% to 6.3% depending on the study. Long-term data are not yet available but a 52-week open label extension to these short-term studies and a 26-week efficacy maintenance study are currently under way.

What we really need are studies that tell us whether the gains in BED frequency are maintained after you stop Vyvanse. Otherwise, we’re talking about indefinite treatment on a controlled substance.

Since all stimulants reduce appetite and weight, a reasonable assumption is that any methylphenidate or amphetamine formulation would also be effective for BED. So far, we’ve found no other published studies evaluating other stimulants, although the site clinicaltrials.gov lists an ongoing study comparing extended release methylphenidate and cognitive behavior therapy.

Other BED Treatments

The widely accepted first-line treatment for BED is psychotherapy, particularly cognitive behavior therapy. A 2010 meta-analysis found that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychotherapy had larger effect sizes (in the range of 0.8) than studies of medications (effect sizes around 0.5). (Vocks et al, Int J Eat Disord 2010;43(3):205–217). However, there are no head-to-head studies actually comparing therapy with meds for BED, and this meta-analysis did not include the more recent pharmacotherapy studies including those with Vyvanse.

(Ed note: For some great and timeless tips on therapeutic strategies for patients who binge, please see our interview with Cynthia Bulik in TCPR October 2007.)

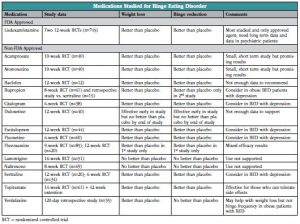

A more recent review of medication options for BED (Goracci A et al, J Addict Med 2015;9:1–19) is helpful, because it describes the strengths and weaknesses of studies of a wide range of medications (see chart below for a summary). The majority of SSRI studies showed they are significantly more effective than placebo for reducing frequency of binge eating, weight and severity of illness. The data are mixed on bupropion, but it is effective for weight loss. Topiramate (Topamax) at doses ranging from 25–600 mg/d (mostly in the 100–300 mg/day range) is effective for BED symptoms and for weight loss but unfortunately is quite poorly tolerated due to cognitive impairment, sedation, and other side effects. These side effects are less likely to be an issue if you keep the dose below 200 mg/day.

Our Recommendations

Before prescribing any medication for BED, do a thoughtful evaluation and make sure that the diagnosis isn’t actually obesity due to overeating. Ask carefully about their eating schedules and get into all the details. Asking patients to come back in two weeks with a food diary is helpful. Patients who are simply overweight should generally be referred to a weight loss specialist.

If BED is indeed the issue, start with cognitive behavior therapy, and consider SSRIs if there are underlying mood issues (there is a 40% lifetime prevalence of depression in BED). Reserve Vyvanse for patients who don’t respond to these treatments, and consider trying other, cheaper stimulants first. While there’s nothing wrong with being an early adopter of new meds (or a new indication for an existing med), in this case there are significant risks of abuse and diversion, so factor this carefully into your decision-making process.

TCPR Verdict: Vyvanse is a solid medication option for BED...but it’s only one option out of many, and a particularly risky one in terms of diversion and abuse.

General PsychiatryAmid some controversy, BED made its formal diagnostic debut in DSM 5 in 2013. For a diagnosis of BED, a patient has to have recurring episodes (at least once a week over three months) of binge eating, which means a time limited (DSM-5 suggests 2 hours) period of eating significantly more food than most people would consider normal, coupled with a sense of loss of control of eating. There are two main differences between BED and bulimia nervosa (BN): (1) Patients with BED don’t purge or exercise excessively to prevent weight gain; (2) They aren’t “inappropriately” concerned with body image or body shape.

Given the combination of binge eating and the lack of compensatory behaviors, you won’t be surprised to hear that patients with BED gain weight. In fact, estimates are that up to 90% of patients with BED are overweight to obese. Which brings up another issue—is BED just another term for overeating? This is a crucial distinction because being overweight or obese affects 69% of the US, whereas BED as strictly defined has a prevalence of about 2% in men and 3.5% in women (Hudson JI et al, Biol Psychiatry 2007;61(3):348–358). With Vyvanse now approved for BED, the concern is that it will be prescribed indiscriminately for overweight patients. Flashback to the 1960s, when “diet doctors” and weight loss clinics prescribed FDA-approved amphetamines for weight loss, fueling the amphetamine epidemic that led directly to Congress creating our current system of controlled substances (Rasmussen N, Am J Public Heath 2008;98(6):974–985, free full text online here).

We’ll go through the data on Vyvanse and briefly compare it with other potential treatments for BED, then give you some recommendations.

Vyvanse for BED: The Data

FDA approval was based on two Shire-sponsored, short term (12-week) studies with a total of 745 adults with moderate to severe BED (Citrome L Int J Clin Pract 2015;69(4):410–421). Patients were excluded if they had substance use disorders, ADHD, depression or anxiety—which might reduce the generalizability of the results for psychiatric practitioners, since we’re unlikely to be treating otherwise psychiatrically healthy binge eaters. Those patients will see their PCPs.

Patients enrolled in the studies were bingeing an average of about 5 days per week. Those randomized to receive 50 mg/day or 70 mg/day of Vyvanse reported a reduction of 3.9 bingeing days per week compared to a decrease of about 2.4 bingeing days per week with the placebo. Effect sizes for Vyvanse were large and ranged from 0.83–0.97. But on secondary measures assessing depression, anxiety and other psychiatric symptoms, Vyvanse did not beat placebo.

An earlier proof of concept study showed 30 mg/day was not more effective than placebo (McElroy SL et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(3):235–246), explaining the choice of doses for these studies. Patients on Vyvanse lost 6% of their body weight during the study—significantly more than patients on placebo who were essentially weight neutral.

The side effects more common with Vyvanse than placebo were dry mouth (36% vs 7%), insomnia (20% vs 8%), decreased appetite (8% vs 2%), increased heart rate (7% vs 1%), feeling jittery (6% vs 1%) and anxiety (5% vs 1%). Nonetheless, the rate of discontinuation from Vyvanse was low, ranging from 1.5% to 6.3% depending on the study. Long-term data are not yet available but a 52-week open label extension to these short-term studies and a 26-week efficacy maintenance study are currently under way.

What we really need are studies that tell us whether the gains in BED frequency are maintained after you stop Vyvanse. Otherwise, we’re talking about indefinite treatment on a controlled substance.

Since all stimulants reduce appetite and weight, a reasonable assumption is that any methylphenidate or amphetamine formulation would also be effective for BED. So far, we’ve found no other published studies evaluating other stimulants, although the site clinicaltrials.gov lists an ongoing study comparing extended release methylphenidate and cognitive behavior therapy.

Table: Vyvanse for Binge Eating Disorder - At a Glance

Click to view full-size table as a PDF.

Other BED Treatments

The widely accepted first-line treatment for BED is psychotherapy, particularly cognitive behavior therapy. A 2010 meta-analysis found that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychotherapy had larger effect sizes (in the range of 0.8) than studies of medications (effect sizes around 0.5). (Vocks et al, Int J Eat Disord 2010;43(3):205–217). However, there are no head-to-head studies actually comparing therapy with meds for BED, and this meta-analysis did not include the more recent pharmacotherapy studies including those with Vyvanse.

(Ed note: For some great and timeless tips on therapeutic strategies for patients who binge, please see our interview with Cynthia Bulik in TCPR October 2007.)

A more recent review of medication options for BED (Goracci A et al, J Addict Med 2015;9:1–19) is helpful, because it describes the strengths and weaknesses of studies of a wide range of medications (see chart below for a summary). The majority of SSRI studies showed they are significantly more effective than placebo for reducing frequency of binge eating, weight and severity of illness. The data are mixed on bupropion, but it is effective for weight loss. Topiramate (Topamax) at doses ranging from 25–600 mg/d (mostly in the 100–300 mg/day range) is effective for BED symptoms and for weight loss but unfortunately is quite poorly tolerated due to cognitive impairment, sedation, and other side effects. These side effects are less likely to be an issue if you keep the dose below 200 mg/day.

Table: Medications Studied for BED

Click to view full-size table as PDF.

Our Recommendations

Before prescribing any medication for BED, do a thoughtful evaluation and make sure that the diagnosis isn’t actually obesity due to overeating. Ask carefully about their eating schedules and get into all the details. Asking patients to come back in two weeks with a food diary is helpful. Patients who are simply overweight should generally be referred to a weight loss specialist.

If BED is indeed the issue, start with cognitive behavior therapy, and consider SSRIs if there are underlying mood issues (there is a 40% lifetime prevalence of depression in BED). Reserve Vyvanse for patients who don’t respond to these treatments, and consider trying other, cheaper stimulants first. While there’s nothing wrong with being an early adopter of new meds (or a new indication for an existing med), in this case there are significant risks of abuse and diversion, so factor this carefully into your decision-making process.

TCPR Verdict: Vyvanse is a solid medication option for BED...but it’s only one option out of many, and a particularly risky one in terms of diversion and abuse.

Issue Date: June 1, 2015

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)