Home » Screen Media and Mental Health Risks

Screen Media and Mental Health Risks

September 1, 2016

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Mary G. Burke, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist, Sutter Pacific Medical Foundation, San Francisco, CA

Dr. Burke has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

This issue of the Carlat Child Psychiatry Report takes on a topic that is on the minds of child mental health clinicians and (of course) pediatricians, parents, and teachers: Is 24/7 immersion in screen media negatively affecting our children? I have been helping patients of all ages, as well as the general public, address this in practical and socially acceptable ways since 1999.

At that time, I was the consult psychiatrist for a pediatric unit in a public hospital, where the department had recently eliminated its Child Life program, moving media consoles into children’s rooms. I found a disconcerting number of children who were zoning out in front of their screens, with their anxious parents telling me that their children had become depressed and were refusing to interact or even make eye contact. I was also deluged with requests to address what appeared to be emotional numbing. I concluded that the steady exposure to media was the most likely cause of the complaints I was hearing. These problems started to resolve when our team helped parents reconnect with their children using games, puzzles, books, and even audio books. When I left the hospital, Child Life had been reinstated, and I began my quest to understand the impact of screen media on children.

The intent of this article is not to assert that screen media are harmful when used appropriately. The majority of us use the internet and our devices regularly and find them essential for learning and communication. However, screen media are not biologically neutral. As I will discuss, they are, by design, addictive for susceptible individuals; further, they are deleterious for babies and must be used wisely with young children. As children mature, they need to learn how to use screen media ethically and in moderation. This is a developmental task for which evolution has not prepared us.

Screen media guidelines

I’ve developed a set of guidelines, based on age range, that I share with parents as well as with my teen and adult patients.

Children under 2

Think of screens as the equivalent of a caffeinated beverage. Both give that pleasurable dopamine hit to help us do things that need to be done. But some dopamine sources are more detrimental than others, and we try to avoid exposing babies at all costs. Screens also emit blue light, which suppresses melatonin and interferes with sleep (Holzman D, Environ Health Perspect 2010;118(1):A22–A27. doi: 10.1289/ehp.118-a22). And, as we know, babies need a lot of sleep, so I strongly recommend no screens until babies are talking—even better, no screens until babies are talking and potty trained.

Children

From ages 2–7, when imagination, language, and the beginnings of autonomy are developing, I recommend no solo viewing. If your child is watching television or using screens, watch with the child and reinforce verbally what you are seeing. Per the American Academy of Pediatrics 1999 guidelines, I recommend that parents stick with the screen time limits of 10 hours weekly and no more than 2 hours daily until high school (http://tinyurl.com/hfl4k4z). While screens are great for teaching screen-based motor skills and children can indeed learn using them, they also need to learn in the physical world: by building, making, and experimenting. Tasks such as writing and drawing, turning pages, and taking notes are all neurologically different from using screens. Memorizing requires hippocampal activation. The rapid attention shifts and constant alerting that are triggered by screen-based learning are—as every psychiatrist should know—antithetical to the laying down of long-term memories. No existing data suggest that U.S. children’s academic skills are improving as a result of increased access to screen media—in fact, there is some evidence those skills are stagnating or worsening. There are also data showing that requests for ADHD treatment are escalating in the U.S., especially since 2007 (CDC, MMWR 2013;62(24):509). While we don’t know that these findings are causally related, the trend suggests a need for future research. So, for this age group, old-fashioned rules apply:

Pre-adolescents and adolescents

By upper-middle school and high school, laptops and smartphones have become a necessity in most classes. We will need longer-term studies to know when they produce meaningful gains and when they interfere with learning. At present, the U.S. lags behind other developed countries in multiple areas of proficiency, but it is not possible, based on the research to date, to attribute this lag to a single cause. When my son’s school implemented a “bring your own device” policy, he told me that, at any given time, half of his classmates were playing video games or chatting on social media. I regularly poll my teen patients on this topic, and they confirm this is often the case. Teens still need to learn the skills to moderate their use, and may not be able to simply “turn off,” especially at night. Less confrontational remedies at home include switching off the home internet at night and linking the privilege of device ownership to appropriate use.

Research behind the recommendations

Rates of use

According to a massive 2015 survey, U.S. teenagers use an average of nine hours of entertainment media daily, while tweens use an average of six hours daily. These numbers don’t include time spent using media for school or homework. Mobile devices now account for 40%–46% of screen time (http://tinyurl.com/jb4v4ac). This study confirmed prior surveys that noted high rates of rapid, sequential attention shifts (euphemistically known as multitasking) with simultaneous use of multiple screen media and applications available through those media. Among 13- to 17-year-olds, 34% admit using their phones almost constantly (Lenhart A, Pew Research Center 2015). In 2013, a Common Sense Media survey found 0- to 12-month-olds were spending 44 minutes daily watching screens and were being read to daily for 19 minutes; at 24 months, the number changed to 60 minutes of screen time and 29 minutes of reading (https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/zero-to-eight-childrens-media-use-in-america-2013).

Behavioral studies

Television is bad for babies: It interrupts play, decreases interactions with parents, and interferes with sleep. Children who watch more screen media early in life show delays in language and reading, and display hyperactivity. Adults talk less to babies when there is more television in the background. Television decreases the development of imagination in children. Higher screen usage in toddlers is associated with poor emotion regulation. Lastly, an observational study of families in public spaces found parents are less attuned and harsher with toddlers when they use their own devices (Radesky J et al, Pediatrics 2014;133(4):843–849).

As an infant-parent specialist, I highlight that screen media are especially toxic in the early years because they are non-contingent, non-attuned stimuli. The development of shared mental space or “intersubjectivity” is the foundation of empathy, the ability to keep an internal sense of connection to others, and distress tolerance. Devices are designed to be personal, not shared. Interactive games have an outcome that is ultimately programmed. A baby’s early feats of self-directed imagination and change-producing interactions are essential to mental health. Engagement with unresponsive others “may be the principal mechanism for actualizing genetic potentials for developmentally destructive responses toward both the environment and the self” (Bronfenbrenner U and Ceci S, Psychol Rev 1994;101(4):568–586). Translating this to modern terms, when babies try to interact with non-responsive environments, it triggers stress, which cumulatively causes epigenetic changes and alterations in neuronal pathways. The “still face” and “visual cliff” experiments of attachment researchers have robustly proven this. Screens are not really responsive, nor are parents who are themselves on devices.

In older children, reducing exposure specifically to violent screen media reduces aggressive behavior and obesity (Robinson T et al, JAMA 1999;282:1561–1567; Singer M et al, Pediatrics 1999;(104):878–884). Screen media exposure is directly and epidemiologically linked to eating disorders (Derenne J and Beresin J, Academic Psychiatry 2006;30(3):237–261). Even exposure to social assertiveness—often the mainstay of reality television—may be associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in bullying and other types of behavioral problems. In addition, multitasking impairs studying and grades in middle school through college (Rosen LD et al, Computers in Human Behavior 2013;29:948–958).

Brain (mechanistic) studies of screen media

Children’s television shows are designed to produce “pop”—sudden visual shifts that stimulate the alerting system and keep the viewer connected. For example, in a study on the effects of fast-paced television shows on young children, the popular animated series SpongeBob SquarePants—with its active animation, rapid scene changes, and constant movement—negatively affected executive function, cognition, and self-regulation in 4-year-old children (Christakis DA, Pediatrics 2011;128(4):772–774). Both social media sites and a host of online games with frequent “updates” harness the brain systems underlying pleasurable anticipation, an especially motivating emotion system. Certain content—such as violence and sex—is especially activating to the human brain and so tends to generate more addictive behaviors.

The dopamine (DA) reward system is activated while playing video games (Koepp et al, Nature 1988;393:266–268). Video game addicts, identified using Young’s Internet Addiction Test, showed reduced striatal dopamine transporter activity (Hou H et al, J Biomed Biotech 2012;2012:854524. doi: 10.1155/2012/854524). The DA reward system reinforces motor behavior that has a survival value. DA release while we are learning a new behavior increases the likelihood that we will repeat that motor action. In phase two of learning, DA activation moves to the motor system: We are driven to the physical acts that will give us our DA hit. Over time, we feel uncomfortable if we don’t do the motor action (Dobrin C, Roberts D. The Anatomy of Addiction. In: Ries RK et al. The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009). Screen media fool our brains into thinking that sitting still in front of a screen and pressing a button is good for our survival. There are innate differences in humans regarding susceptibility to various addictions, but the biology remains the same—including the fact that the earlier the exposure, the higher the likelihood of addiction.

Studies in the last 10 years have revealed significant alterations in brain metabolism and connectivity, and even evidence of atrophy, in heavy video game users (Yuan K et al, PLoS ONE 2011;6(6):e20708. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020708). Teen gamers show loss of gray matter density (Zhou Y et al, Eur J Radiol 2011;79(1):92–95). Heavy gamers undergoing MRI while playing showed deactivation in the areas responsible for emotion regulation and executive function. There was a reciprocal activation of regions coordinating visual and physical activity. This study revealed how video games can lead to desensitization to violence in heavy users (Mathiak K and Weber R, Human Brain Mapping 2006;27:948–956).

A substantial body of imaging studies confirms that heavy (over 21 hours/week) video game users show reduced activation of frontal lobe areas that underlie emotion regulation and executive function. Even short media-free periods increase empathy (Uhls Y et al, Computers in Human Behavior 2014;39:387–392).

Recommendations for clinicians

It would be helpful if we could draw from large-scale, prospective studies of exactly how screen media use affects mental health for children of all ages, but no such research seems to be in the offing in the near future. Perhaps such studies, when done, will provide a more robust picture of the ways in which screen media can be used to strengthen rather than adversely affect our children’s health. In the meantime, I encourage you as a clinician to review your current practices regarding exploring screen media use in your patients. I believe it should be as much a part of an assessment and ongoing monitoring as questions about use of illegal substances, tobacco, alcohol, and risky behaviors. Failing to explore any of these issues can make therapeutic progress impossible if, in fact, they are the underlying problem.

Recommendations for patients

Working with patients and families, I’ve met numerous parental objections when I’ve suggested that screen media is negatively affecting their child or adolescent. When I encounter such resistance, some of my responses have included:

The accompanying table lists some strategies that I have found useful for encouraging parents to model acceptable screen media use at home. In my experience, once patients and families get past their resistance to change, they come to appreciate the results; however, like any behavioral intervention, persistence and follow-through are crucial.

Conclusion

Screen media are neurologically potent, abnormal sensory inputs that produce changes in brain function and neuron connectivity. Like that morning cup of coffee, this is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does mean we have to pay attention to how and when our children are exposed (“the dose makes the poison”). I have worked with patients of all ages for whom it was clear that media overexposure was the primary etiology of their symptoms. However, in most cases screen media exposure is a complicating factor. In distress, people (like my hospitalized pediatric patients) seek quick relief and gratification, and other necessary skill sets either atrophy or fail to develop.

By helping families limit media exposure, I have witnessed the reduction or disappearance of children’s symptoms of OCD, panic attacks, insomnia, enuresis, nightmares, and apparent psychosis. I have been able to “undiagnose” bipolar disorder in children who actually had ADHD or learning disabilities, but who were spending too much time on the computer and too little time doing other things (and were possibly being overstimulated by excess blue light). In children with underlying vulnerabilities, I have found that screen media interferes with the development of coping strategies, including reflection, social relatedness, creativity, and self-soothing in the face of adversity. Patients—parents and/or children—may disagree with screen media limitations at first, but the large majority are happy with the beneficial results.

Child PsychiatryAt that time, I was the consult psychiatrist for a pediatric unit in a public hospital, where the department had recently eliminated its Child Life program, moving media consoles into children’s rooms. I found a disconcerting number of children who were zoning out in front of their screens, with their anxious parents telling me that their children had become depressed and were refusing to interact or even make eye contact. I was also deluged with requests to address what appeared to be emotional numbing. I concluded that the steady exposure to media was the most likely cause of the complaints I was hearing. These problems started to resolve when our team helped parents reconnect with their children using games, puzzles, books, and even audio books. When I left the hospital, Child Life had been reinstated, and I began my quest to understand the impact of screen media on children.

The intent of this article is not to assert that screen media are harmful when used appropriately. The majority of us use the internet and our devices regularly and find them essential for learning and communication. However, screen media are not biologically neutral. As I will discuss, they are, by design, addictive for susceptible individuals; further, they are deleterious for babies and must be used wisely with young children. As children mature, they need to learn how to use screen media ethically and in moderation. This is a developmental task for which evolution has not prepared us.

Screen media guidelines

I’ve developed a set of guidelines, based on age range, that I share with parents as well as with my teen and adult patients.

Children under 2

Think of screens as the equivalent of a caffeinated beverage. Both give that pleasurable dopamine hit to help us do things that need to be done. But some dopamine sources are more detrimental than others, and we try to avoid exposing babies at all costs. Screens also emit blue light, which suppresses melatonin and interferes with sleep (Holzman D, Environ Health Perspect 2010;118(1):A22–A27. doi: 10.1289/ehp.118-a22). And, as we know, babies need a lot of sleep, so I strongly recommend no screens until babies are talking—even better, no screens until babies are talking and potty trained.

Children

From ages 2–7, when imagination, language, and the beginnings of autonomy are developing, I recommend no solo viewing. If your child is watching television or using screens, watch with the child and reinforce verbally what you are seeing. Per the American Academy of Pediatrics 1999 guidelines, I recommend that parents stick with the screen time limits of 10 hours weekly and no more than 2 hours daily until high school (http://tinyurl.com/hfl4k4z). While screens are great for teaching screen-based motor skills and children can indeed learn using them, they also need to learn in the physical world: by building, making, and experimenting. Tasks such as writing and drawing, turning pages, and taking notes are all neurologically different from using screens. Memorizing requires hippocampal activation. The rapid attention shifts and constant alerting that are triggered by screen-based learning are—as every psychiatrist should know—antithetical to the laying down of long-term memories. No existing data suggest that U.S. children’s academic skills are improving as a result of increased access to screen media—in fact, there is some evidence those skills are stagnating or worsening. There are also data showing that requests for ADHD treatment are escalating in the U.S., especially since 2007 (CDC, MMWR 2013;62(24):509). While we don’t know that these findings are causally related, the trend suggests a need for future research. So, for this age group, old-fashioned rules apply:

- No screen time until homework is done.

- Make sure kids get outside and run around every day.

- Have children deposit phones in a designated place upon arriving at home, where they remain off.

- No smartphones until children are old enough to purchase them and pay for data.

Pre-adolescents and adolescents

By upper-middle school and high school, laptops and smartphones have become a necessity in most classes. We will need longer-term studies to know when they produce meaningful gains and when they interfere with learning. At present, the U.S. lags behind other developed countries in multiple areas of proficiency, but it is not possible, based on the research to date, to attribute this lag to a single cause. When my son’s school implemented a “bring your own device” policy, he told me that, at any given time, half of his classmates were playing video games or chatting on social media. I regularly poll my teen patients on this topic, and they confirm this is often the case. Teens still need to learn the skills to moderate their use, and may not be able to simply “turn off,” especially at night. Less confrontational remedies at home include switching off the home internet at night and linking the privilege of device ownership to appropriate use.

Research behind the recommendations

Rates of use

According to a massive 2015 survey, U.S. teenagers use an average of nine hours of entertainment media daily, while tweens use an average of six hours daily. These numbers don’t include time spent using media for school or homework. Mobile devices now account for 40%–46% of screen time (http://tinyurl.com/jb4v4ac). This study confirmed prior surveys that noted high rates of rapid, sequential attention shifts (euphemistically known as multitasking) with simultaneous use of multiple screen media and applications available through those media. Among 13- to 17-year-olds, 34% admit using their phones almost constantly (Lenhart A, Pew Research Center 2015). In 2013, a Common Sense Media survey found 0- to 12-month-olds were spending 44 minutes daily watching screens and were being read to daily for 19 minutes; at 24 months, the number changed to 60 minutes of screen time and 29 minutes of reading (https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/zero-to-eight-childrens-media-use-in-america-2013).

Behavioral studies

Television is bad for babies: It interrupts play, decreases interactions with parents, and interferes with sleep. Children who watch more screen media early in life show delays in language and reading, and display hyperactivity. Adults talk less to babies when there is more television in the background. Television decreases the development of imagination in children. Higher screen usage in toddlers is associated with poor emotion regulation. Lastly, an observational study of families in public spaces found parents are less attuned and harsher with toddlers when they use their own devices (Radesky J et al, Pediatrics 2014;133(4):843–849).

As an infant-parent specialist, I highlight that screen media are especially toxic in the early years because they are non-contingent, non-attuned stimuli. The development of shared mental space or “intersubjectivity” is the foundation of empathy, the ability to keep an internal sense of connection to others, and distress tolerance. Devices are designed to be personal, not shared. Interactive games have an outcome that is ultimately programmed. A baby’s early feats of self-directed imagination and change-producing interactions are essential to mental health. Engagement with unresponsive others “may be the principal mechanism for actualizing genetic potentials for developmentally destructive responses toward both the environment and the self” (Bronfenbrenner U and Ceci S, Psychol Rev 1994;101(4):568–586). Translating this to modern terms, when babies try to interact with non-responsive environments, it triggers stress, which cumulatively causes epigenetic changes and alterations in neuronal pathways. The “still face” and “visual cliff” experiments of attachment researchers have robustly proven this. Screens are not really responsive, nor are parents who are themselves on devices.

In older children, reducing exposure specifically to violent screen media reduces aggressive behavior and obesity (Robinson T et al, JAMA 1999;282:1561–1567; Singer M et al, Pediatrics 1999;(104):878–884). Screen media exposure is directly and epidemiologically linked to eating disorders (Derenne J and Beresin J, Academic Psychiatry 2006;30(3):237–261). Even exposure to social assertiveness—often the mainstay of reality television—may be associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in bullying and other types of behavioral problems. In addition, multitasking impairs studying and grades in middle school through college (Rosen LD et al, Computers in Human Behavior 2013;29:948–958).

Brain (mechanistic) studies of screen media

Children’s television shows are designed to produce “pop”—sudden visual shifts that stimulate the alerting system and keep the viewer connected. For example, in a study on the effects of fast-paced television shows on young children, the popular animated series SpongeBob SquarePants—with its active animation, rapid scene changes, and constant movement—negatively affected executive function, cognition, and self-regulation in 4-year-old children (Christakis DA, Pediatrics 2011;128(4):772–774). Both social media sites and a host of online games with frequent “updates” harness the brain systems underlying pleasurable anticipation, an especially motivating emotion system. Certain content—such as violence and sex—is especially activating to the human brain and so tends to generate more addictive behaviors.

The dopamine (DA) reward system is activated while playing video games (Koepp et al, Nature 1988;393:266–268). Video game addicts, identified using Young’s Internet Addiction Test, showed reduced striatal dopamine transporter activity (Hou H et al, J Biomed Biotech 2012;2012:854524. doi: 10.1155/2012/854524). The DA reward system reinforces motor behavior that has a survival value. DA release while we are learning a new behavior increases the likelihood that we will repeat that motor action. In phase two of learning, DA activation moves to the motor system: We are driven to the physical acts that will give us our DA hit. Over time, we feel uncomfortable if we don’t do the motor action (Dobrin C, Roberts D. The Anatomy of Addiction. In: Ries RK et al. The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009). Screen media fool our brains into thinking that sitting still in front of a screen and pressing a button is good for our survival. There are innate differences in humans regarding susceptibility to various addictions, but the biology remains the same—including the fact that the earlier the exposure, the higher the likelihood of addiction.

Studies in the last 10 years have revealed significant alterations in brain metabolism and connectivity, and even evidence of atrophy, in heavy video game users (Yuan K et al, PLoS ONE 2011;6(6):e20708. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020708). Teen gamers show loss of gray matter density (Zhou Y et al, Eur J Radiol 2011;79(1):92–95). Heavy gamers undergoing MRI while playing showed deactivation in the areas responsible for emotion regulation and executive function. There was a reciprocal activation of regions coordinating visual and physical activity. This study revealed how video games can lead to desensitization to violence in heavy users (Mathiak K and Weber R, Human Brain Mapping 2006;27:948–956).

A substantial body of imaging studies confirms that heavy (over 21 hours/week) video game users show reduced activation of frontal lobe areas that underlie emotion regulation and executive function. Even short media-free periods increase empathy (Uhls Y et al, Computers in Human Behavior 2014;39:387–392).

Recommendations for clinicians

It would be helpful if we could draw from large-scale, prospective studies of exactly how screen media use affects mental health for children of all ages, but no such research seems to be in the offing in the near future. Perhaps such studies, when done, will provide a more robust picture of the ways in which screen media can be used to strengthen rather than adversely affect our children’s health. In the meantime, I encourage you as a clinician to review your current practices regarding exploring screen media use in your patients. I believe it should be as much a part of an assessment and ongoing monitoring as questions about use of illegal substances, tobacco, alcohol, and risky behaviors. Failing to explore any of these issues can make therapeutic progress impossible if, in fact, they are the underlying problem.

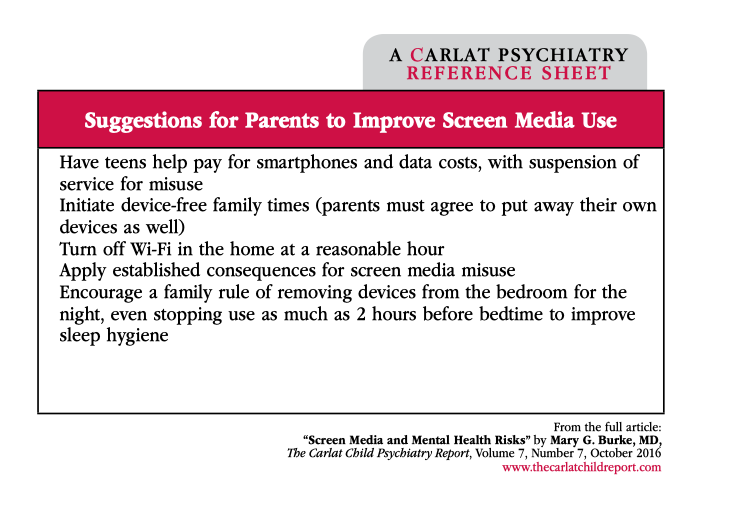

Table: Suggestions for Parents to Improve Screen Media Use

(Click here to view full-size PDF.)

Recommendations for patients

Working with patients and families, I’ve met numerous parental objections when I’ve suggested that screen media is negatively affecting their child or adolescent. When I encounter such resistance, some of my responses have included:

- “You’ve been worried about possible side effects from stimulants; turning off the TV may decrease the need for medication.”

- “I can’t guarantee this will end your child’s depression, but I don’t think your child can get better until you limit screen media use.”

- “Try cutting back for a month, and we’ll reassess.”

- “What are some of the positive activities that you and your child have stopped doing because of screen media use? Let’s focus on getting back to those fun/creative/meaningful activities.”

The accompanying table lists some strategies that I have found useful for encouraging parents to model acceptable screen media use at home. In my experience, once patients and families get past their resistance to change, they come to appreciate the results; however, like any behavioral intervention, persistence and follow-through are crucial.

Conclusion

Screen media are neurologically potent, abnormal sensory inputs that produce changes in brain function and neuron connectivity. Like that morning cup of coffee, this is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does mean we have to pay attention to how and when our children are exposed (“the dose makes the poison”). I have worked with patients of all ages for whom it was clear that media overexposure was the primary etiology of their symptoms. However, in most cases screen media exposure is a complicating factor. In distress, people (like my hospitalized pediatric patients) seek quick relief and gratification, and other necessary skill sets either atrophy or fail to develop.

By helping families limit media exposure, I have witnessed the reduction or disappearance of children’s symptoms of OCD, panic attacks, insomnia, enuresis, nightmares, and apparent psychosis. I have been able to “undiagnose” bipolar disorder in children who actually had ADHD or learning disabilities, but who were spending too much time on the computer and too little time doing other things (and were possibly being overstimulated by excess blue light). In children with underlying vulnerabilities, I have found that screen media interferes with the development of coping strategies, including reflection, social relatedness, creativity, and self-soothing in the face of adversity. Patients—parents and/or children—may disagree with screen media limitations at first, but the large majority are happy with the beneficial results.

KEYWORDS registered-articles

Issue Date: September 1, 2016

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)