Home » Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Insomnia

Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Insomnia

April 1, 2017

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Michael Perlis, PhD

Associate professor of psychiatry & nursing, University of Pennsylvania. Director, UPenn Behavioral Sleep Medicine Program

Dr. Perlis has disclosed that he has received funding for research on CBT-I and has received funds from the sales of materials related to the teaching of CBT-I techniques. Dr. Carlat has reviewed this interview and has found no evidence of bias in this educational activity.

Michael Perlis, PhD

Associate professor of psychiatry & nursing, University of Pennsylvania. Director, UPenn Behavioral Sleep Medicine Program

Dr. Perlis has disclosed that he has received funding for research on CBT-I and has received funds from the sales of materials related to the teaching of CBT-I techniques. Dr. Carlat has reviewed this interview and has found no evidence of bias in this educational activity.

TCPR: Dr. Perlis, you are one of the major researchers of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia. Why are you so interested in the topic of insomnia?

Dr. Perlis: Because insomnia is so ubiquitous and misunderstood with respect to its health consequences and “treatability.” At the core of this is the widespread misconception that insomnia is primarily a symptom of other things. In fact, the sleep community bears some responsibility for this, as it has been long been a slogan (since the mid-1980s) that “insomnia is not a disorder; it is a symptom, like a cough or fever.”

TCPR: And how is insomnia not a symptom? Certainly in psychiatry we see insomnia listed in DSM-5 as a symptom of various disorders, like major depression, mania, and anxiety disorders.

Dr. Perlis: It has been true, and continues to be true, that insomnia is listed as a symptom (or feature) of up to 80% of Axis-I DSM disorders. This said, insomnia is also identified in DSM-5 as an independent disorder (780.52) which, when occurring with other DSM-5 disorders, is considered a comorbid disorder rather than a symptom. The research supporting this point of view suggests that insomnia occurs prior to, and is a risk factor for, various psychiatric disorders—and that it makes those disorders harder to successfully treat.

TCPR: What are the implications of reconceptualizing insomnia as a separate disorder?

Dr. Perlis: It means insomnia should be treated, and aggressively so, whether with medication or CBT-I. This brings up another perspective issue. Up to the present, the model for medical treatment has been that insomnia is like chronic pain and hypnotics are like opiates. When sleeping pills are prescribed, patients are told, “Take this only when you need it, and take as low a dose as you can.” But what if this treatment perspective is not correct? What if insomnia is more like an infection and sleeping pills are like antibiotics? In this case, patients would be told, “Never miss a dose, and complete the full regimen.” Maybe this approach to the medical treatment of insomnia would yield more robust results and durable treatment gains.

TCPR: Your point is well taken. How effective is modern treatment for insomnia?

Dr. Perlis: Both CBT-I and hypnotics decrease insomnia by about 50%. After discontinuing CBT-I, 50%–70% of patients maintain their clinical gains. In sharp contrast, those treated with hypnotics show little to no retention of clinical gains when treatment is discontinued. It is for these reasons, and its more benign side effect profile, that CBT-I is now recommended as the treatment for chronic insomnia by the American College of Physicians (https://tinyurl.com/gmzqdox).

TCPR: A lot of the studies that I’ve seen on CBT-I have been focused on so-called “primary insomnia.” What does that mean, exactly? And would the treatments effective for primary insomnia also be effective for the kinds of insomnia psychiatrists see every day, which are concurrent with psychiatric disorders?

Dr. Perlis: Yes, a lot of the original CBT-I literature was in primary insomnia, in which they recruited rarified individuals with no medical or psychiatric comorbidity. Recently, we have seen much more real-world research of CBT-I with all kinds of patients, including those with psychiatric comorbidity, those with ongoing chronic pain, etc. It turns out the technique is just as effective in all these populations (Geiger-Brown JM, Sleep Med Rev 2015;23:54–67).

TCPR: So how does CBT-I actually work?

Dr. Perlis: CBT-I is typically a weekly, 50-minute therapy session for 8 weeks, though this can vary from as little as 2–4 sessions to as many as 12–16 sessions. Some sessions may be as short as 15 minutes or as long as 120 minutes. The first step is to have patients keep a sleep diary for a couple of weeks, which can be challenging because they’re not receiving treatment during this time. That said, such data are crucial for CBT-I because patients are rarely able to retrospectively report their sleep patterns accurately.

TCPR: What is in a typical sleep diary?

Dr. Perlis: Sleep diaries are typically a set of questions that the patient completes each and every morning. Generally, patients record various measures of sleep, such as when they went to bed, when they got up, how long it took them to fall asleep (so-called “sleep latency”), total sleep time, and other variables. Other relevant factors might include daytime sleepiness, whether they napped, amount and timing of caffeine and nicotine use, etc. [Ed. note: A free sleep diary can be downloaded at https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/SleepDiaryv6.pdf.]

TCPR: And how do you use sleep diary information?

Dr. Perlis: These data are used to create a plan for sleep restriction therapy (ie, a new sleep schedule) and to determine if and when that new sleep schedule should be changed, depending on a variable called sleep efficiency. We also use the data to monitor the other main aspect of CBT-I, which is stimulus control therapy.

TCPR: Let’s take those in order. What is sleep restriction?

Dr. Perlis: The purpose of sleep restriction is to correct the mismatch between sleep opportunity and sleep ability. Let’s say you have a patient who needs to wake up for work at 6 am and sets an alarm. He begins to feel sleepy around 10 pm and gets into bed, but then tosses and turns for an hour or so, falling asleep at about 11 pm. He wakes up a couple of times during the night and estimates that he is awake for another 30 minutes over those combined periods. His sleep opportunity was 8 hours (10 pm to 6 am) but his sleep ability was about 6.5 hours, and therefore the mismatch is about 90 minutes. If his 7- to 14-day sleep diary shows that this represents an average night, his therapist would prescribe a new sleep schedule as the first step in treatment.

TCPR: What would this new sleep schedule look like?

Dr. Perlis: It would be adjusted so there is a better match between sleep opportunity and sleep ability. In this example, the patient’s time in bed would be reduced from 8 hours to 6.5 hours. How the new schedule is set follows a specific protocol and requires a fair amount of explanation to garner patent compliance. After all, the patient comes in thinking more sleep is the answer, but the therapist is effectively recommending less sleep.

TCPR: So once the sleep period is compressed to 6.5 hours, what happens next?

Dr. Perlis: If the patient achieves a good match between sleep opportunity and sleep ability after a week or so on the prescribed sleep schedule, the sleep opportunity would be upwardly titrated by 15 minutes (eg, from 6.5 hours to 6 hours and 45 minutes) and the patient would be evaluated again in a week’s time for progress. This process occurs again and again over the treatment period. If treatment is successful, the patient will fall asleep earlier (reduced sleep latency) and will have less time awake during the night.

TCPR: You had also mentioned stimulus control. What is that?

Dr. Perlis: Frankly, stimulus control is a ridiculously simple and yet complex thing. At its most basic, it is the natural complement of sleep restriction therapy. Sleep restriction sets a schedule that increases the likelihood of solid and efficient sleep, but it does not explicitly tell patients what to do when they wake up at night. This is where stimulus control comes in. If you’re awake at night, don’t spend that time in bed—go elsewhere and return to bed when “sleepy.” But there are other aspects to stimulus control, including suggestions such as “Don’t do anything in the bedroom apart from sleep and sex,” “Keep a regular bedtime,” and regardless of how you sleep (a good or bad night), “Get out of bed the same time each and every day.” All of these things likely contribute to the efficacy of stimulus control, particularly as a component of CBT-I.

TCPR: So let’s return to the nuts and bolts of the therapy sessions. How exactly does the therapy progress?

Dr. Perlis: The first couple of sessions are primarily assessment, using both questionnaires and sleep diaries to determine if the patient is a good and appropriate candidate for CBT-I. For example, we would assess what factors (eg, comorbidities and/or life circumstances) are likely to complicate the use of CBT-I. Central to this assessment is the documentation of coexisting medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, and other possible sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, parasomnias, etc.).

TCPR: And if there is a comorbidity, what do you do? Do you proceed with CBT-I, or do you wait for the other condition to be treated?

Dr. Perlis: That depends on the nature of the comorbid condition. With most chronic and stable comorbidities, there is no reason to delay the use of CBT-I. In fact, the use of CBT-I may provide for better outcomes with some of the comorbid conditions; this appears to be especially true in the case of depression. At the end of the day, the decision to use CBT-I is related to a few key points: 1) Is the insomnia of sufficient severity and frequency to warrant treatment? 2) Is there something about the patient or the patient’s comorbid condition(s) that would prevent the standard use of CBT-I (or its use at all)? 3) Is there something about CBT-I that may exacerbate the patient’s comorbid condition(s) that poses an unacceptable risk, even in the short term? If the answers are “yes,” “no,” and “no,” CBT-I is indicated.

TCPR: Can you give an example of common difficulties patients have with the therapy?

Dr. Perlis: I could think of 10 right off the bat. But here’s the one that is usually the first of the classic patient resistances. Regardless of how much you prepare patients, it still comes as something of a shock that they won’t be going to bed when sleepy. Instead (in keeping with our earlier example), the bedtime will be delayed by an hour and a half. So instead of going to bed at 10 pm, the patient’s new bedtime is 11:30 pm. At the moment this number is on the table, the patient invariably says, “I don’t think I can stay awake until then,” to which the therapist replies, “That sounds like we’re on the right track!” In truth, this moment is the first step of what some might call cognitive therapy—it represents the opportunity to reframe the patient’s treatment expectations from “I need to get more sleep” to “I’d be happy with less sleep if I fell asleep quickly and stayed asleep for most of the night.”

TCPR: A lot of what you describe seems to overlap with “sleep hygiene.” Most psychiatrists know a bit about sleep hygiene, and we often talk to patients about it and hand them a sheet with tips. Is this effective?

Dr. Perlis: Giving patients a list of tips, like avoiding too much alcohol before bedtime or trying not to take naps during the day, can be helpful, but there’s no clinical trial evidence that such recommendations alone improve sleep. In fact, sleep researchers often use sleep hygiene as a control condition for trials of CBT-I because it’s considered to be ineffective on its own. What worries me most about such well-intended interventions is the patient’s belief that sleep hygiene is CBT-I, and this may deter the patient from seeking out evidence-based CBT-I as delivered by an experienced clinician.

TCPR: I think one of the reasons sleep hygiene tips are popular is that it’s hard for us to find qualified therapists in our areas who can provide CBT-I.

Dr. Perlis: That’s fair. However, there are more CBT-I therapists today than ever before. If you are considering making a referral for CBT-I, there are several compendiums you can find by Googling “CBT-I provider directory.” Most states also have specialists who can provide treatment via telehealth. Finally, there are CBT-I packages on the internet, like Shut-I and Sleepio. Randomized controlled trials of these programs have shown them to be effective, though it is not clear that they are as effective as in-person treatment.

TCPR: How does one find out about CBT-I training?

Dr. Perlis: You can find a list of CE trainings at our website (http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/cont_ed.html). We are in the process of providing a full list of CE trainings (see http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/ and click “Continuing Education: CBT-I and BSM” in the left bar menu). In addition to UPenn, there are also other universities that have such trainings, including VA, UMass, Ryerson University, and Oxford University. You can also purchase CBT-I products at PESI (https://pesi.com) and CBT-I Educational Products (http://www.cbtieducationalproducts.com/).

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Perlis.

General PsychiatryDr. Perlis: Because insomnia is so ubiquitous and misunderstood with respect to its health consequences and “treatability.” At the core of this is the widespread misconception that insomnia is primarily a symptom of other things. In fact, the sleep community bears some responsibility for this, as it has been long been a slogan (since the mid-1980s) that “insomnia is not a disorder; it is a symptom, like a cough or fever.”

TCPR: And how is insomnia not a symptom? Certainly in psychiatry we see insomnia listed in DSM-5 as a symptom of various disorders, like major depression, mania, and anxiety disorders.

Dr. Perlis: It has been true, and continues to be true, that insomnia is listed as a symptom (or feature) of up to 80% of Axis-I DSM disorders. This said, insomnia is also identified in DSM-5 as an independent disorder (780.52) which, when occurring with other DSM-5 disorders, is considered a comorbid disorder rather than a symptom. The research supporting this point of view suggests that insomnia occurs prior to, and is a risk factor for, various psychiatric disorders—and that it makes those disorders harder to successfully treat.

TCPR: What are the implications of reconceptualizing insomnia as a separate disorder?

Dr. Perlis: It means insomnia should be treated, and aggressively so, whether with medication or CBT-I. This brings up another perspective issue. Up to the present, the model for medical treatment has been that insomnia is like chronic pain and hypnotics are like opiates. When sleeping pills are prescribed, patients are told, “Take this only when you need it, and take as low a dose as you can.” But what if this treatment perspective is not correct? What if insomnia is more like an infection and sleeping pills are like antibiotics? In this case, patients would be told, “Never miss a dose, and complete the full regimen.” Maybe this approach to the medical treatment of insomnia would yield more robust results and durable treatment gains.

TCPR: Your point is well taken. How effective is modern treatment for insomnia?

Dr. Perlis: Both CBT-I and hypnotics decrease insomnia by about 50%. After discontinuing CBT-I, 50%–70% of patients maintain their clinical gains. In sharp contrast, those treated with hypnotics show little to no retention of clinical gains when treatment is discontinued. It is for these reasons, and its more benign side effect profile, that CBT-I is now recommended as the treatment for chronic insomnia by the American College of Physicians (https://tinyurl.com/gmzqdox).

TCPR: A lot of the studies that I’ve seen on CBT-I have been focused on so-called “primary insomnia.” What does that mean, exactly? And would the treatments effective for primary insomnia also be effective for the kinds of insomnia psychiatrists see every day, which are concurrent with psychiatric disorders?

Dr. Perlis: Yes, a lot of the original CBT-I literature was in primary insomnia, in which they recruited rarified individuals with no medical or psychiatric comorbidity. Recently, we have seen much more real-world research of CBT-I with all kinds of patients, including those with psychiatric comorbidity, those with ongoing chronic pain, etc. It turns out the technique is just as effective in all these populations (Geiger-Brown JM, Sleep Med Rev 2015;23:54–67).

TCPR: So how does CBT-I actually work?

Dr. Perlis: CBT-I is typically a weekly, 50-minute therapy session for 8 weeks, though this can vary from as little as 2–4 sessions to as many as 12–16 sessions. Some sessions may be as short as 15 minutes or as long as 120 minutes. The first step is to have patients keep a sleep diary for a couple of weeks, which can be challenging because they’re not receiving treatment during this time. That said, such data are crucial for CBT-I because patients are rarely able to retrospectively report their sleep patterns accurately.

TCPR: What is in a typical sleep diary?

Dr. Perlis: Sleep diaries are typically a set of questions that the patient completes each and every morning. Generally, patients record various measures of sleep, such as when they went to bed, when they got up, how long it took them to fall asleep (so-called “sleep latency”), total sleep time, and other variables. Other relevant factors might include daytime sleepiness, whether they napped, amount and timing of caffeine and nicotine use, etc. [Ed. note: A free sleep diary can be downloaded at https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/SleepDiaryv6.pdf.]

TCPR: And how do you use sleep diary information?

Dr. Perlis: These data are used to create a plan for sleep restriction therapy (ie, a new sleep schedule) and to determine if and when that new sleep schedule should be changed, depending on a variable called sleep efficiency. We also use the data to monitor the other main aspect of CBT-I, which is stimulus control therapy.

TCPR: Let’s take those in order. What is sleep restriction?

Dr. Perlis: The purpose of sleep restriction is to correct the mismatch between sleep opportunity and sleep ability. Let’s say you have a patient who needs to wake up for work at 6 am and sets an alarm. He begins to feel sleepy around 10 pm and gets into bed, but then tosses and turns for an hour or so, falling asleep at about 11 pm. He wakes up a couple of times during the night and estimates that he is awake for another 30 minutes over those combined periods. His sleep opportunity was 8 hours (10 pm to 6 am) but his sleep ability was about 6.5 hours, and therefore the mismatch is about 90 minutes. If his 7- to 14-day sleep diary shows that this represents an average night, his therapist would prescribe a new sleep schedule as the first step in treatment.

TCPR: What would this new sleep schedule look like?

Dr. Perlis: It would be adjusted so there is a better match between sleep opportunity and sleep ability. In this example, the patient’s time in bed would be reduced from 8 hours to 6.5 hours. How the new schedule is set follows a specific protocol and requires a fair amount of explanation to garner patent compliance. After all, the patient comes in thinking more sleep is the answer, but the therapist is effectively recommending less sleep.

TCPR: So once the sleep period is compressed to 6.5 hours, what happens next?

Dr. Perlis: If the patient achieves a good match between sleep opportunity and sleep ability after a week or so on the prescribed sleep schedule, the sleep opportunity would be upwardly titrated by 15 minutes (eg, from 6.5 hours to 6 hours and 45 minutes) and the patient would be evaluated again in a week’s time for progress. This process occurs again and again over the treatment period. If treatment is successful, the patient will fall asleep earlier (reduced sleep latency) and will have less time awake during the night.

TCPR: You had also mentioned stimulus control. What is that?

Dr. Perlis: Frankly, stimulus control is a ridiculously simple and yet complex thing. At its most basic, it is the natural complement of sleep restriction therapy. Sleep restriction sets a schedule that increases the likelihood of solid and efficient sleep, but it does not explicitly tell patients what to do when they wake up at night. This is where stimulus control comes in. If you’re awake at night, don’t spend that time in bed—go elsewhere and return to bed when “sleepy.” But there are other aspects to stimulus control, including suggestions such as “Don’t do anything in the bedroom apart from sleep and sex,” “Keep a regular bedtime,” and regardless of how you sleep (a good or bad night), “Get out of bed the same time each and every day.” All of these things likely contribute to the efficacy of stimulus control, particularly as a component of CBT-I.

TCPR: So let’s return to the nuts and bolts of the therapy sessions. How exactly does the therapy progress?

Dr. Perlis: The first couple of sessions are primarily assessment, using both questionnaires and sleep diaries to determine if the patient is a good and appropriate candidate for CBT-I. For example, we would assess what factors (eg, comorbidities and/or life circumstances) are likely to complicate the use of CBT-I. Central to this assessment is the documentation of coexisting medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, and other possible sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, parasomnias, etc.).

TCPR: And if there is a comorbidity, what do you do? Do you proceed with CBT-I, or do you wait for the other condition to be treated?

Dr. Perlis: That depends on the nature of the comorbid condition. With most chronic and stable comorbidities, there is no reason to delay the use of CBT-I. In fact, the use of CBT-I may provide for better outcomes with some of the comorbid conditions; this appears to be especially true in the case of depression. At the end of the day, the decision to use CBT-I is related to a few key points: 1) Is the insomnia of sufficient severity and frequency to warrant treatment? 2) Is there something about the patient or the patient’s comorbid condition(s) that would prevent the standard use of CBT-I (or its use at all)? 3) Is there something about CBT-I that may exacerbate the patient’s comorbid condition(s) that poses an unacceptable risk, even in the short term? If the answers are “yes,” “no,” and “no,” CBT-I is indicated.

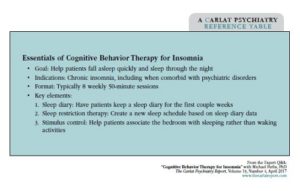

Table: Essentials of Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Insomnia

(Click here to view full-size PDF)

TCPR: Can you give an example of common difficulties patients have with the therapy?

Dr. Perlis: I could think of 10 right off the bat. But here’s the one that is usually the first of the classic patient resistances. Regardless of how much you prepare patients, it still comes as something of a shock that they won’t be going to bed when sleepy. Instead (in keeping with our earlier example), the bedtime will be delayed by an hour and a half. So instead of going to bed at 10 pm, the patient’s new bedtime is 11:30 pm. At the moment this number is on the table, the patient invariably says, “I don’t think I can stay awake until then,” to which the therapist replies, “That sounds like we’re on the right track!” In truth, this moment is the first step of what some might call cognitive therapy—it represents the opportunity to reframe the patient’s treatment expectations from “I need to get more sleep” to “I’d be happy with less sleep if I fell asleep quickly and stayed asleep for most of the night.”

TCPR: A lot of what you describe seems to overlap with “sleep hygiene.” Most psychiatrists know a bit about sleep hygiene, and we often talk to patients about it and hand them a sheet with tips. Is this effective?

Dr. Perlis: Giving patients a list of tips, like avoiding too much alcohol before bedtime or trying not to take naps during the day, can be helpful, but there’s no clinical trial evidence that such recommendations alone improve sleep. In fact, sleep researchers often use sleep hygiene as a control condition for trials of CBT-I because it’s considered to be ineffective on its own. What worries me most about such well-intended interventions is the patient’s belief that sleep hygiene is CBT-I, and this may deter the patient from seeking out evidence-based CBT-I as delivered by an experienced clinician.

TCPR: I think one of the reasons sleep hygiene tips are popular is that it’s hard for us to find qualified therapists in our areas who can provide CBT-I.

Dr. Perlis: That’s fair. However, there are more CBT-I therapists today than ever before. If you are considering making a referral for CBT-I, there are several compendiums you can find by Googling “CBT-I provider directory.” Most states also have specialists who can provide treatment via telehealth. Finally, there are CBT-I packages on the internet, like Shut-I and Sleepio. Randomized controlled trials of these programs have shown them to be effective, though it is not clear that they are as effective as in-person treatment.

TCPR: How does one find out about CBT-I training?

Dr. Perlis: You can find a list of CE trainings at our website (http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/cont_ed.html). We are in the process of providing a full list of CE trainings (see http://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/ and click “Continuing Education: CBT-I and BSM” in the left bar menu). In addition to UPenn, there are also other universities that have such trainings, including VA, UMass, Ryerson University, and Oxford University. You can also purchase CBT-I products at PESI (https://pesi.com) and CBT-I Educational Products (http://www.cbtieducationalproducts.com/).

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Perlis.

Issue Date: April 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)