Home » Differentiating Psychotic Disorders: Does It Matter?

EXPERT Q&A

Differentiating Psychotic Disorders: Does It Matter?

May 7, 2020

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Jonathan Stevens, MD, MPH

Jonathan Stevens, MD, MPH

Chief of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Chief of Outpatient Services at The Menninger Clinic in Houston, TX.

Dr. Stevens has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CCPR: Tell us a little about what you do and where you work.

Dr. Stevens: In my role at The Menninger Clinic, I am responsible for developing and supervising personalized mental health care services for people receiving outpatient care. We diagnose and treat people who live in or travel to Houston seeking the highest-quality mental health care.

CCPR: You co-authored a primer on psychotic disorders in children and adolescents (Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014;16(2):PCC.13f01514). My big question is about the practicality of focusing on differences between the various DSM-5 psychotic disorders, including bipolar disorder and trauma syndromes and such things as autoimmune encephalopathies.

Dr. Stevens: Psychotic symptoms can occur in the context of numerous psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia. You just mentioned a few, but I would also add depression, anxiety, ADHD, post-traumatic states, and autism spectrum disorders; psychosis can also be secondary to a wide variety of medical conditions. There may be differences in the expression of psychosis based on the primary diagnosis. For example, pediatric patients with bipolar disorder often experience hallucinations and delusions but can also have the clinical characteristics of mania, of depression, or of both. In children with hallucinations related to psychological trauma, patients or their parents may report nightmares and trance-like states.

CCPR: We talk about anxiety along a spectrum and depression along a spectrum. What about psychosis along a spectrum?

Dr. Stevens: I tend to think about psychosis along a chronological or developmental spectrum rather than a spectrum of symptom severity. Often, prior to the onset of psychosis, youth who go on to develop schizophrenia show nonspecific, irregular, or unusual social and cognitive development. In retrospect, we refer to this as the prodrome, or the period linking premorbid functioning to the psychotic “break” or full psychosis. Clinically, patients may show social withdrawal or behavior that is apathetic, eccentric, or suspicious. These prodromal symptoms are often misdiagnosed as part of a depressive disorder.

CCPR: How do you unpack all that?

Dr. Stevens: It’s difficult. Many researchers are interested in the possibility of diagnosing schizophrenia in children during this prodromal period. Two research groups have developed criteria and structured interviews to aid in diagnosis of prodromal psychotic symptoms: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS) and Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) (Fusar-Poli P et al, Psychiatry J 2016;2016:7146341). Unfortunately, these complex instruments have limited usefulness in clinical settings.

CCPR: What about patients who report visual phenomena or unusual experiences?

Dr. Stevens: As a rule, a complaint of visual hallucinations makes me suspicious of an underlying delirium or potential medical cause. Your question highlights the importance of completing a thorough medical workup when distinguishing between primary and secondary psychotic disorders. Although there is no generally agreed-upon medical evaluation that every patient with psychosis should undergo, screening tests should be ordered based on a patient’s personal and family history, as well as on one’s clinical suspicion of conditions. Regarding patients who describe atypical or unusual experiences, there may be red flags that cause me to suspect a symptom is not psychotic.

CCPR: Can you give us an example?

Dr. Stevens: Like adult patients, some children and adolescents may complain of symptoms that seem to suggest psychosis but are not the genuine article. If very rare symptoms are reported, if there are no supporting signs of schizophrenia except “voices,” or if the patient says “Let me tell you about my delusion” or “I have been so paranoid about my boyfriend cheating on me,” then I am generally reassured.

CCPR: I’ve had kids describe nighttime phenomena, like seeing things out of the corner of their eye, and it makes me wonder about illusions or non-hallucinatory phenomena.

Dr. Stevens: Me too. The younger the child, the more commonly I hear these descriptions. My differential of this complaint includes a child’s normal nighttime fears, illusions, or active imagination. Five to eight percent of children endorse isolated psychotic symptoms. To put that in perspective, that’s 10 times more than the rate of schizophrenia (van Os J et al, Psychol Med 2009;39(2):179–195). My explanation is that children’s conception and description of their internal world and experience is less formed than in adulthood.

CCPR: Can you talk about early treatment of psychosis?

Dr. Stevens: The notions of early intervention and perhaps even prevention of schizophrenia are at the forefront of early-onset psychosis research. However, the current literature does not support clear treatment guidelines for these vulnerable patients. Outcome studies of child-onset psychosis indicate that the long-term function of patients is poor compared to those with adolescent-onset or adult-onset psychosis (Stevens JR, 2014). This literature makes me inclined to intervene with medication in these early-onset cases. In general, the earlier that chronic psychosis or schizophrenia develops, the worse the prognosis. On the other hand, higher premorbid intelligence, having more positive than negative symptoms, and having family members cooperate in treatment improves the prognosis.

CCPR: Are you are saying there are times when it is better not to watch and wait?

Dr. Stevens: I am more proactive in treating patients who display high-risk behaviors—aggressive or assaultive behavior, or self-injuriousness or suicidality. For example, I recently evaluated a 12-year-old referred by his school counselor for “disruptive behavior” in the classroom. However, on exam, he appeared disorganized, unkempt, and internally preoccupied. He admitted to bolting from the classroom, but at the command of a demeaning voice that was not his own. He went on to tell me about other voices that bothered him most of the day, every day. He was assaultive toward peers, but his episodes of hitting and kicking were haphazard and seemingly unintentional. In my office, he laughed inappropriately and was poorly socialized. His mother was visibly concerned and told me he hadn’t been like this a year ago. She described him as hyperactive and “the class clown,” but not aloof or withdrawn.

CCPR: So how did you treat it?

Dr. Stevens: In this case, the boy had no clear mood symptoms. He carried a historical diagnosis of ADHD, but clearly his presentation had become much more impairing and concerning for an early-onset presentation of psychosis with worrisome chronicity. Given the child’s presentation and elevated risk of harm to others, I prescribed a low dose of aripiprazole. By the next visit, about two weeks later, he showed dramatic, global improvement.

CCPR: What about psychotherapies for people with psychotic disorders?

Dr. Stevens: We can’t treat schizophrenia spectrum disorders with antipsychotic medicine alone. Fortunately, a variety of psychotherapies can be helpful—though I don’t necessarily administer them all myself. I typically employ supportive techniques to shore up my patients’ defenses and then refer them to my colleagues for techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for psychosis. I find that CBT helps patients to evaluate evidence for beliefs or think through explanations surrounding their perceptions; it can thus help to alter dysfunctional behaviors.

CCPR: What about addressing the environment?

Dr. Stevens: Psychosocial interventions can alter the environment to minimize undue stress, which increases vulnerability to psychotic episodes; interventions can also match the level of stimulation to the patient’s level of alertness and overall functioning. And it’s important to note that several studies of adults with psychosis support the usefulness of psychoeducation to decrease medication noncompliance and relapse rates (Xia J et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(6):CD002831).

CCPR: How about situations where patients are using cannabis or other drugs?

Dr. Stevens: There are environmental risks for the development of schizophrenia or aggravating psychosis. It’s pretty clear that “the grass is not greener,” as data from longitudinal studies have shown that regular cannabis use predicts an increased risk for schizophrenia and symptoms of psychosis (Hall W and Degenhard L, World Psychiatry 2008;7(2):68–71). Cannabis use during early adolescence, coupled with suspected genetic vulnerability and changes in brain development, together are correlated with risk for the development of schizophrenia and cognitive decline. However, the direction of the effect has been called into question. Some suggest that individuals with psychosis use cannabis to alleviate their psychotic symptoms or to improve their mood. Others, however, suggest that cannabis causes or exacerbates psychotic symptoms.

CCPR: I’ve had people use the antipsychotic to get rid of their paranoid symptoms so that they can keep smoking weed.

Dr. Stevens: This is where a personalized approach lends itself to a difficult real-world situation. In a clinical trial, a patient wouldn’t be allowed to smoke cannabis to improve sleep. In the clinical world, quetiapine has several clinical uses. You might say, “This medicine could help with the psychosis and make it so you won’t have to smoke a bowl or use a dab pen to fall asleep. Let’s see if you cut down your smoking and your psychosis goes away, then you might not have to be on medicine.” I find that most teens don’t want to be on pills for any reason. A short-term trial on an antipsychotic might be reasonable.

CCPR: Do you find some medications more effective for specific kinds of psychotic disorders?

Dr. Stevens: I use personalized approaches because prescribing according to algorithms alone fails to fully account for diverse presentations of psychosis. Starting with risperidone for a medication-naïve patient is fine, but the outcomes are often partial and symptom reduction insufficient. Moreover, many children, more so than adults, struggle with side effects. Weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and increased cardiovascular risk shave years off the lives of patients with psychosis. Increasingly, I find pharmacogenetic testing to be helpful for patients before initiating medicine or for those who struggle with adverse medication effects.

CCPR: Tell us more about how you use pharmacogenetic testing.

Dr. Stevens: Recent advances in pharmacogenetic testing allow for more precise or targeted pharmacology for children and adolescents struggling with psychotic disorders. For example, genetic variants in the dopamine-2 receptor can make an individual youth 35% less likely to respond to an agent and might explain a history of prior treatment failures (Zhang JP et al, Am J Psychiatry 2010;167(7):763–772). Antipsychotic-associated weight gain is related to genetic variants in the melanocortin-4 receptor or the serotonin-2C receptor. Certain variants in these genes are associated with 2 to 3 times increased risk of clinically significant weight gain during atypical antipsychotic treatment.

CCPR: Marketed tests may not check these, and we need to differentiate metabolism from clinical efficacy, but with all the marketing, it’s good to hear about the potential utility for pharmacogenetic testing. Do you use metformin?

Dr. Stevens: Metformin is one agent I use to moderate antipsychotic-associated weight gain. Other agents, such as phentermine or topiramate, I use less frequently. There’s a lot more room for development of agents that could alleviate the metabolic burdens of antipsychotic medicine.

CCPR: How do you talk to patients and families about medication?

Dr. Stevens: I explain that treatment of psychotic symptoms is similar in many ways to the treatment of infection with antibiotics—the clinician needs to choose the proper medication at a sufficient dose and then await therapeutic results while monitoring for potential side effects. I try to convey that efficacy differences of antipsychotics in adolescent-onset schizophrenia seem to be relatively small, except for clozapine in treatment-refractory patients; however, side effect differences across antipsychotics are relatively large and predictable. (Editor’s note: The COVID-19 pandemic demands careful planning of clozapine lab follow-up.)

CCPR: How does this discussion with patients and families unfold over time?

Dr. Stevens: True informed consent is ongoing discussion over several visits. In the first visit or when starting a new medicine, I discuss common initial side effects of antipsychotics such as drowsiness, dry mouth, nasal congestion, or blurred vision. Caregivers can usually manage the short-term adverse effects by adjusting the dose and the timing of administration. They might be able to avoid sedation by using less-sedating agents and by prescribing most of the daily dose at bedtime. Then we discuss weight gain as an intermediate-term risk. I believe in using the lowest dose of medicine possible to decrease the risk of side effects, but even with the best of intentions, treatment-interfering side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, akathisia, or prolactin elevations may occur.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Stevens.

Child Psychiatry Expert Q&ADr. Stevens: In my role at The Menninger Clinic, I am responsible for developing and supervising personalized mental health care services for people receiving outpatient care. We diagnose and treat people who live in or travel to Houston seeking the highest-quality mental health care.

CCPR: You co-authored a primer on psychotic disorders in children and adolescents (Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014;16(2):PCC.13f01514). My big question is about the practicality of focusing on differences between the various DSM-5 psychotic disorders, including bipolar disorder and trauma syndromes and such things as autoimmune encephalopathies.

Dr. Stevens: Psychotic symptoms can occur in the context of numerous psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia. You just mentioned a few, but I would also add depression, anxiety, ADHD, post-traumatic states, and autism spectrum disorders; psychosis can also be secondary to a wide variety of medical conditions. There may be differences in the expression of psychosis based on the primary diagnosis. For example, pediatric patients with bipolar disorder often experience hallucinations and delusions but can also have the clinical characteristics of mania, of depression, or of both. In children with hallucinations related to psychological trauma, patients or their parents may report nightmares and trance-like states.

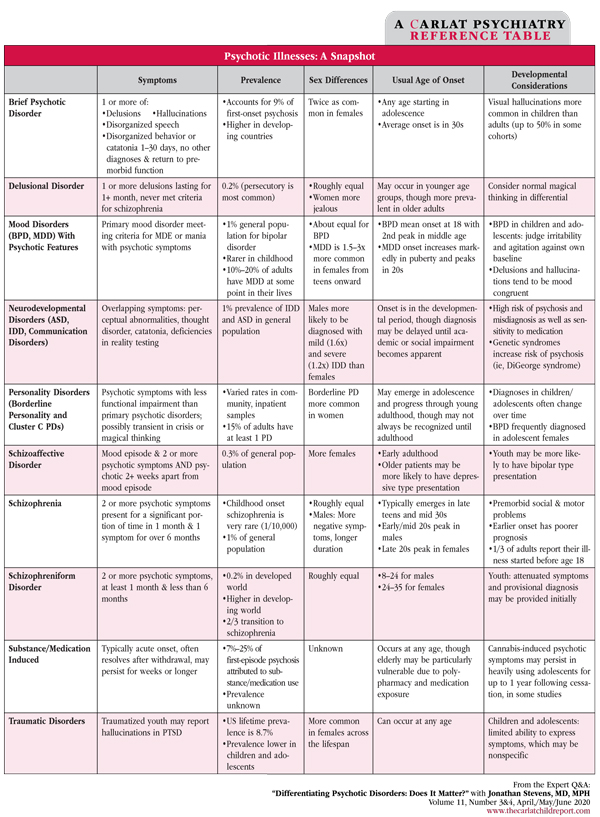

Table: Psychotic Illnesses: A Snapshot

(Click for full-size PDF)

CCPR: We talk about anxiety along a spectrum and depression along a spectrum. What about psychosis along a spectrum?

Dr. Stevens: I tend to think about psychosis along a chronological or developmental spectrum rather than a spectrum of symptom severity. Often, prior to the onset of psychosis, youth who go on to develop schizophrenia show nonspecific, irregular, or unusual social and cognitive development. In retrospect, we refer to this as the prodrome, or the period linking premorbid functioning to the psychotic “break” or full psychosis. Clinically, patients may show social withdrawal or behavior that is apathetic, eccentric, or suspicious. These prodromal symptoms are often misdiagnosed as part of a depressive disorder.

CCPR: How do you unpack all that?

Dr. Stevens: It’s difficult. Many researchers are interested in the possibility of diagnosing schizophrenia in children during this prodromal period. Two research groups have developed criteria and structured interviews to aid in diagnosis of prodromal psychotic symptoms: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS) and Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) (Fusar-Poli P et al, Psychiatry J 2016;2016:7146341). Unfortunately, these complex instruments have limited usefulness in clinical settings.

CCPR: What about patients who report visual phenomena or unusual experiences?

Dr. Stevens: As a rule, a complaint of visual hallucinations makes me suspicious of an underlying delirium or potential medical cause. Your question highlights the importance of completing a thorough medical workup when distinguishing between primary and secondary psychotic disorders. Although there is no generally agreed-upon medical evaluation that every patient with psychosis should undergo, screening tests should be ordered based on a patient’s personal and family history, as well as on one’s clinical suspicion of conditions. Regarding patients who describe atypical or unusual experiences, there may be red flags that cause me to suspect a symptom is not psychotic.

CCPR: Can you give us an example?

Dr. Stevens: Like adult patients, some children and adolescents may complain of symptoms that seem to suggest psychosis but are not the genuine article. If very rare symptoms are reported, if there are no supporting signs of schizophrenia except “voices,” or if the patient says “Let me tell you about my delusion” or “I have been so paranoid about my boyfriend cheating on me,” then I am generally reassured.

CCPR: I’ve had kids describe nighttime phenomena, like seeing things out of the corner of their eye, and it makes me wonder about illusions or non-hallucinatory phenomena.

Dr. Stevens: Me too. The younger the child, the more commonly I hear these descriptions. My differential of this complaint includes a child’s normal nighttime fears, illusions, or active imagination. Five to eight percent of children endorse isolated psychotic symptoms. To put that in perspective, that’s 10 times more than the rate of schizophrenia (van Os J et al, Psychol Med 2009;39(2):179–195). My explanation is that children’s conception and description of their internal world and experience is less formed than in adulthood.

CCPR: Can you talk about early treatment of psychosis?

Dr. Stevens: The notions of early intervention and perhaps even prevention of schizophrenia are at the forefront of early-onset psychosis research. However, the current literature does not support clear treatment guidelines for these vulnerable patients. Outcome studies of child-onset psychosis indicate that the long-term function of patients is poor compared to those with adolescent-onset or adult-onset psychosis (Stevens JR, 2014). This literature makes me inclined to intervene with medication in these early-onset cases. In general, the earlier that chronic psychosis or schizophrenia develops, the worse the prognosis. On the other hand, higher premorbid intelligence, having more positive than negative symptoms, and having family members cooperate in treatment improves the prognosis.

CCPR: Are you are saying there are times when it is better not to watch and wait?

Dr. Stevens: I am more proactive in treating patients who display high-risk behaviors—aggressive or assaultive behavior, or self-injuriousness or suicidality. For example, I recently evaluated a 12-year-old referred by his school counselor for “disruptive behavior” in the classroom. However, on exam, he appeared disorganized, unkempt, and internally preoccupied. He admitted to bolting from the classroom, but at the command of a demeaning voice that was not his own. He went on to tell me about other voices that bothered him most of the day, every day. He was assaultive toward peers, but his episodes of hitting and kicking were haphazard and seemingly unintentional. In my office, he laughed inappropriately and was poorly socialized. His mother was visibly concerned and told me he hadn’t been like this a year ago. She described him as hyperactive and “the class clown,” but not aloof or withdrawn.

CCPR: So how did you treat it?

Dr. Stevens: In this case, the boy had no clear mood symptoms. He carried a historical diagnosis of ADHD, but clearly his presentation had become much more impairing and concerning for an early-onset presentation of psychosis with worrisome chronicity. Given the child’s presentation and elevated risk of harm to others, I prescribed a low dose of aripiprazole. By the next visit, about two weeks later, he showed dramatic, global improvement.

CCPR: What about psychotherapies for people with psychotic disorders?

Dr. Stevens: We can’t treat schizophrenia spectrum disorders with antipsychotic medicine alone. Fortunately, a variety of psychotherapies can be helpful—though I don’t necessarily administer them all myself. I typically employ supportive techniques to shore up my patients’ defenses and then refer them to my colleagues for techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for psychosis. I find that CBT helps patients to evaluate evidence for beliefs or think through explanations surrounding their perceptions; it can thus help to alter dysfunctional behaviors.

CCPR: What about addressing the environment?

Dr. Stevens: Psychosocial interventions can alter the environment to minimize undue stress, which increases vulnerability to psychotic episodes; interventions can also match the level of stimulation to the patient’s level of alertness and overall functioning. And it’s important to note that several studies of adults with psychosis support the usefulness of psychoeducation to decrease medication noncompliance and relapse rates (Xia J et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(6):CD002831).

CCPR: How about situations where patients are using cannabis or other drugs?

Dr. Stevens: There are environmental risks for the development of schizophrenia or aggravating psychosis. It’s pretty clear that “the grass is not greener,” as data from longitudinal studies have shown that regular cannabis use predicts an increased risk for schizophrenia and symptoms of psychosis (Hall W and Degenhard L, World Psychiatry 2008;7(2):68–71). Cannabis use during early adolescence, coupled with suspected genetic vulnerability and changes in brain development, together are correlated with risk for the development of schizophrenia and cognitive decline. However, the direction of the effect has been called into question. Some suggest that individuals with psychosis use cannabis to alleviate their psychotic symptoms or to improve their mood. Others, however, suggest that cannabis causes or exacerbates psychotic symptoms.

CCPR: I’ve had people use the antipsychotic to get rid of their paranoid symptoms so that they can keep smoking weed.

Dr. Stevens: This is where a personalized approach lends itself to a difficult real-world situation. In a clinical trial, a patient wouldn’t be allowed to smoke cannabis to improve sleep. In the clinical world, quetiapine has several clinical uses. You might say, “This medicine could help with the psychosis and make it so you won’t have to smoke a bowl or use a dab pen to fall asleep. Let’s see if you cut down your smoking and your psychosis goes away, then you might not have to be on medicine.” I find that most teens don’t want to be on pills for any reason. A short-term trial on an antipsychotic might be reasonable.

CCPR: Do you find some medications more effective for specific kinds of psychotic disorders?

Dr. Stevens: I use personalized approaches because prescribing according to algorithms alone fails to fully account for diverse presentations of psychosis. Starting with risperidone for a medication-naïve patient is fine, but the outcomes are often partial and symptom reduction insufficient. Moreover, many children, more so than adults, struggle with side effects. Weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and increased cardiovascular risk shave years off the lives of patients with psychosis. Increasingly, I find pharmacogenetic testing to be helpful for patients before initiating medicine or for those who struggle with adverse medication effects.

CCPR: Tell us more about how you use pharmacogenetic testing.

Dr. Stevens: Recent advances in pharmacogenetic testing allow for more precise or targeted pharmacology for children and adolescents struggling with psychotic disorders. For example, genetic variants in the dopamine-2 receptor can make an individual youth 35% less likely to respond to an agent and might explain a history of prior treatment failures (Zhang JP et al, Am J Psychiatry 2010;167(7):763–772). Antipsychotic-associated weight gain is related to genetic variants in the melanocortin-4 receptor or the serotonin-2C receptor. Certain variants in these genes are associated with 2 to 3 times increased risk of clinically significant weight gain during atypical antipsychotic treatment.

CCPR: Marketed tests may not check these, and we need to differentiate metabolism from clinical efficacy, but with all the marketing, it’s good to hear about the potential utility for pharmacogenetic testing. Do you use metformin?

Dr. Stevens: Metformin is one agent I use to moderate antipsychotic-associated weight gain. Other agents, such as phentermine or topiramate, I use less frequently. There’s a lot more room for development of agents that could alleviate the metabolic burdens of antipsychotic medicine.

CCPR: How do you talk to patients and families about medication?

Dr. Stevens: I explain that treatment of psychotic symptoms is similar in many ways to the treatment of infection with antibiotics—the clinician needs to choose the proper medication at a sufficient dose and then await therapeutic results while monitoring for potential side effects. I try to convey that efficacy differences of antipsychotics in adolescent-onset schizophrenia seem to be relatively small, except for clozapine in treatment-refractory patients; however, side effect differences across antipsychotics are relatively large and predictable. (Editor’s note: The COVID-19 pandemic demands careful planning of clozapine lab follow-up.)

CCPR: How does this discussion with patients and families unfold over time?

Dr. Stevens: True informed consent is ongoing discussion over several visits. In the first visit or when starting a new medicine, I discuss common initial side effects of antipsychotics such as drowsiness, dry mouth, nasal congestion, or blurred vision. Caregivers can usually manage the short-term adverse effects by adjusting the dose and the timing of administration. They might be able to avoid sedation by using less-sedating agents and by prescribing most of the daily dose at bedtime. Then we discuss weight gain as an intermediate-term risk. I believe in using the lowest dose of medicine possible to decrease the risk of side effects, but even with the best of intentions, treatment-interfering side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, akathisia, or prolactin elevations may occur.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Stevens.

Issue Date: May 7, 2020

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)