Home » Principles of Trauma Informed Care

Principles of Trauma Informed Care

August 5, 2020

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Rehan Aziz, MD.

Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Dr. Aziz has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Trauma is common and takes on many forms: abuse, neglect, disaster, displacement, and illness. According to the CDC, at least 1 in 7 children have experienced child abuse or neglect in the past year and, depending on the source, about 1 in 3 to 4 girls and 1 in 5 to 13 boys will experience childhood sexual abuse (www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect; www.preventchildabuse.org). In mental health settings, the prevalence of trauma is even greater. Added to the already high frequency of baseline trauma, there is a significant likelihood that any psychiatric patient has a trauma history. Clinicians, then, should approach all patients with this presumption.

Further, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has created fear, displacement, economic disaster, and loss, potentially leading to an explosive increase in trauma. Worsening the situation, mental health care services have been impeded by the cessation of in-person visits, potential lack of online access for some patients, and decrease in actual service availability. Minority patients, already at higher risk for traumatic histories owing largely to social and systemic inequities, are suffering far more than others. Patients may also have concerns about discussing sensitive information virtually. All of these factors have increased our patients’ vulnerability during this time. The concept of trauma informed care (TIC) offers a framework for understanding and addressing the needs of patients. It promotes developing a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing. This article will offer an overview of TIC and discuss ways to integrate it into your practice.

Impact of trauma

Trauma creates problems. It produces toxic, chronic stress. This causes sympathetic nervous system activation, resulting in a wide range of physical and psychological symptoms. In childhood, exposure to violence increases the risk of injury, future violence, substance use, STDs, delayed brain development, and lower educational attainment. In adulthood, those with childhood exposures have a significantly higher risk for alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders; depression; and suicide attempts. Physically, they have greater chances of developing severe obesity, ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease. These findings from the classic studies by Felitti have given way to an entire field focused on adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs (Felitti VJ et al, Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245–258).

More recent research has defined a wide range of trauma-related problems, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and epigenetic changes. These epigenetic changes in genomic activity place the person and their descendants at a higher level of internal arousal and can shorten telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. The result is a lower threshold for reactivity and higher rates of chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and adult-onset diabetes.

Resist re-traumatization

Unfortunately, patients can become unintentionally re-traumatized in health care, which may cause them to develop anxiety about treatment, avoid medical care altogether, or mistrust clinical settings. In particular, when a child or teen is subjected to rigid behavioral approaches that fail to begin with empathic efforts to understand their perspective, the patient may become more upset, receiving negative labels such as “oppositional” or “assaultive” rather than helpful care. One example of how this can happen is by using restraints on a child who’s been sexually abused. Another is placing a child who’s been neglected or abandoned in a seclusion room. In office settings, patients may become re-traumatized when they:

Diagnoses that are symptom based and neglect a trauma history can also be problematic. Treatment may focus exclusively on pharmacotherapy and/or CBT rather than a more appropriate family therapy, trauma-informed psychotherapy, or child protection role. Research in the field of pediatric bipolar disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (Parry, 2012) and other diagnostic categories such as ADHD has mostly been based on symptom rating scales. However, these scales miss the role of trauma or fail to consider the adaptive function of symptoms arising from a trauma context, such as fight/flight/freeze/appease reactions that manifest as oppositionality, anxiety, avoidance, dissociation, inattention, and manic-defense excitability.

Principles of TIC

Employing TIC can reduce the negative impact of assessment and treatment for children and teens who have suffered traumatic experiences. Principles of TIC include:

Asking about trauma

Pay attention to the setting—is the child comfortable? Helping the child to be regulated is key to connecting adequately and then communicating effectively to get a history about difficult moments. If possible, it is important to minimize the number of interviews, as asking the child over and over about their experiences can be traumatizing for the child (and the interviewer) and lead to the child simply giving rote recitations, which may be less accurate. Where appropriate, have parents help soothe the child. Although you need to obtain a lot of information—the who, what, where, when, and how—try to avoid interrogating the child. Instead of question formats, try calm, gentle statements: reflecting your need for help vs commanding the child to provide information. When the child seems uncomfortable, back off and talk about other things for a bit. Be careful to neither lead the child nor allow yourself or a parent to answer for the child.

When employing the TIC framework, don’t press patients to describe their history in emotionally exhausting detail. While technique modifications may be needed in the age of online therapy, younger children often find it easier to express aspects of their trauma histories through play, and a consulting room with adequate play space and materials such as doll houses and sand trays with figurines can allow for enactment and catharsis of attachment trauma experiences. The clinician can gently interpret, narrate, or inquire about the child’s play, and the child may then verbalize their experiences and feelings. Sometimes, using paper-and-pencil instruments or self-report tools for screening and assessment is less threatening and allows patients to pace themselves in relating their story. Talk about how you’ll use the findings to plan treatment. Discuss any immediate action necessary, like arranging for personal support, referring to community agencies, or proceeding straight to the active phase of care. Solicit feedback and comments from the patient. At the end of the session, make sure the patient is safe before leaving (SAMHSA, Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, 2014; HHS Pub. No. 13-4801).

What do we tell parents and families?

We recommend reinforcing your treatment goals to family members using a statement like this: “Your child needs to feel safe in order for us to treat her effectively. We need to recognize that her symptoms may be at least partly due to the difficult situation she’s experienced. Control and trust were taken away from her, and it’s important we work together to help her build back her trust and sense of control.”

CCPR Verdict: The impact of trauma is ubiquitous in everyday clinical practice and is often hiding beneath the surface. Our practice needs to reflect this reality. Using TIC avoids re-traumatization and helps to provide security and safety for patients, while keeping them engaged in treatment. TIC should be a part of every clinical encounter.

Child PsychiatryFurther, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has created fear, displacement, economic disaster, and loss, potentially leading to an explosive increase in trauma. Worsening the situation, mental health care services have been impeded by the cessation of in-person visits, potential lack of online access for some patients, and decrease in actual service availability. Minority patients, already at higher risk for traumatic histories owing largely to social and systemic inequities, are suffering far more than others. Patients may also have concerns about discussing sensitive information virtually. All of these factors have increased our patients’ vulnerability during this time. The concept of trauma informed care (TIC) offers a framework for understanding and addressing the needs of patients. It promotes developing a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing. This article will offer an overview of TIC and discuss ways to integrate it into your practice.

Impact of trauma

Trauma creates problems. It produces toxic, chronic stress. This causes sympathetic nervous system activation, resulting in a wide range of physical and psychological symptoms. In childhood, exposure to violence increases the risk of injury, future violence, substance use, STDs, delayed brain development, and lower educational attainment. In adulthood, those with childhood exposures have a significantly higher risk for alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders; depression; and suicide attempts. Physically, they have greater chances of developing severe obesity, ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease. These findings from the classic studies by Felitti have given way to an entire field focused on adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs (Felitti VJ et al, Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245–258).

More recent research has defined a wide range of trauma-related problems, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and epigenetic changes. These epigenetic changes in genomic activity place the person and their descendants at a higher level of internal arousal and can shorten telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. The result is a lower threshold for reactivity and higher rates of chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and adult-onset diabetes.

Resist re-traumatization

Unfortunately, patients can become unintentionally re-traumatized in health care, which may cause them to develop anxiety about treatment, avoid medical care altogether, or mistrust clinical settings. In particular, when a child or teen is subjected to rigid behavioral approaches that fail to begin with empathic efforts to understand their perspective, the patient may become more upset, receiving negative labels such as “oppositional” or “assaultive” rather than helpful care. One example of how this can happen is by using restraints on a child who’s been sexually abused. Another is placing a child who’s been neglected or abandoned in a seclusion room. In office settings, patients may become re-traumatized when they:

- Don’t feel safe and secure

- Feel unseen/unheard

- Feel they don’t have any control

- Think that treatment is not

- collaborative

- Have to continually repeat their story

- Believe their trust has been violated (tinyurl.com/v3fp3pg)

- Have no chance to provide feedback

Diagnoses that are symptom based and neglect a trauma history can also be problematic. Treatment may focus exclusively on pharmacotherapy and/or CBT rather than a more appropriate family therapy, trauma-informed psychotherapy, or child protection role. Research in the field of pediatric bipolar disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (Parry, 2012) and other diagnostic categories such as ADHD has mostly been based on symptom rating scales. However, these scales miss the role of trauma or fail to consider the adaptive function of symptoms arising from a trauma context, such as fight/flight/freeze/appease reactions that manifest as oppositionality, anxiety, avoidance, dissociation, inattention, and manic-defense excitability.

Principles of TIC

Employing TIC can reduce the negative impact of assessment and treatment for children and teens who have suffered traumatic experiences. Principles of TIC include:

- Safety—Everyone works to ensure the patient’s physical and emotional security.

- Choice—Patients are supported in making choices regarding their care. Self-advocacy skills are developed.

- Collaboration—Clinicians and patients partner to share power and decision making.

- Trustworthiness—Decision making is transparent. Patients are respected and professional boundaries are followed.

- Empowerment—The patient’s strengths are recognized and built upon, along with the belief that they can recover from trauma. It’s also important to create a culture that allows patients to feel validated and supported (SAMHSA, Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach, 2014; HHS Pub. No. 14-4884).

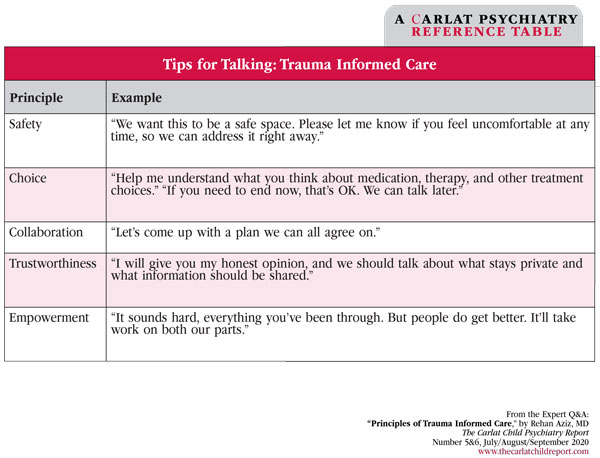

Table: Tips for Talking: Trauma Informed Care

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

Asking about trauma

Pay attention to the setting—is the child comfortable? Helping the child to be regulated is key to connecting adequately and then communicating effectively to get a history about difficult moments. If possible, it is important to minimize the number of interviews, as asking the child over and over about their experiences can be traumatizing for the child (and the interviewer) and lead to the child simply giving rote recitations, which may be less accurate. Where appropriate, have parents help soothe the child. Although you need to obtain a lot of information—the who, what, where, when, and how—try to avoid interrogating the child. Instead of question formats, try calm, gentle statements: reflecting your need for help vs commanding the child to provide information. When the child seems uncomfortable, back off and talk about other things for a bit. Be careful to neither lead the child nor allow yourself or a parent to answer for the child.

When employing the TIC framework, don’t press patients to describe their history in emotionally exhausting detail. While technique modifications may be needed in the age of online therapy, younger children often find it easier to express aspects of their trauma histories through play, and a consulting room with adequate play space and materials such as doll houses and sand trays with figurines can allow for enactment and catharsis of attachment trauma experiences. The clinician can gently interpret, narrate, or inquire about the child’s play, and the child may then verbalize their experiences and feelings. Sometimes, using paper-and-pencil instruments or self-report tools for screening and assessment is less threatening and allows patients to pace themselves in relating their story. Talk about how you’ll use the findings to plan treatment. Discuss any immediate action necessary, like arranging for personal support, referring to community agencies, or proceeding straight to the active phase of care. Solicit feedback and comments from the patient. At the end of the session, make sure the patient is safe before leaving (SAMHSA, Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, 2014; HHS Pub. No. 13-4801).

What do we tell parents and families?

We recommend reinforcing your treatment goals to family members using a statement like this: “Your child needs to feel safe in order for us to treat her effectively. We need to recognize that her symptoms may be at least partly due to the difficult situation she’s experienced. Control and trust were taken away from her, and it’s important we work together to help her build back her trust and sense of control.”

CCPR Verdict: The impact of trauma is ubiquitous in everyday clinical practice and is often hiding beneath the surface. Our practice needs to reflect this reality. Using TIC avoids re-traumatization and helps to provide security and safety for patients, while keeping them engaged in treatment. TIC should be a part of every clinical encounter.

KEYWORDS adverse-childhood-experiences-aces assessment minority pandemic toxic-stress trauma trauma-informed-care

Issue Date: August 5, 2020

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)