Medication Treatments for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorder in Older Adults

Rehan Aziz, MD. Associate program director, Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Program, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune, NJ; associate professor of psychiatry and neurology, Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, Nutley, NJ.

Dr. Aziz has no financial relationships with companies related to this material.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) and opioid use disorder (OUD) are becoming more common in older adults. Several FDA-approved medications can help, but there are no published guidelines for older adults. In this primer, we’ll discuss the pros and cons of medication-assisted therapy (MAT) options in older adults.

Medications for AUD

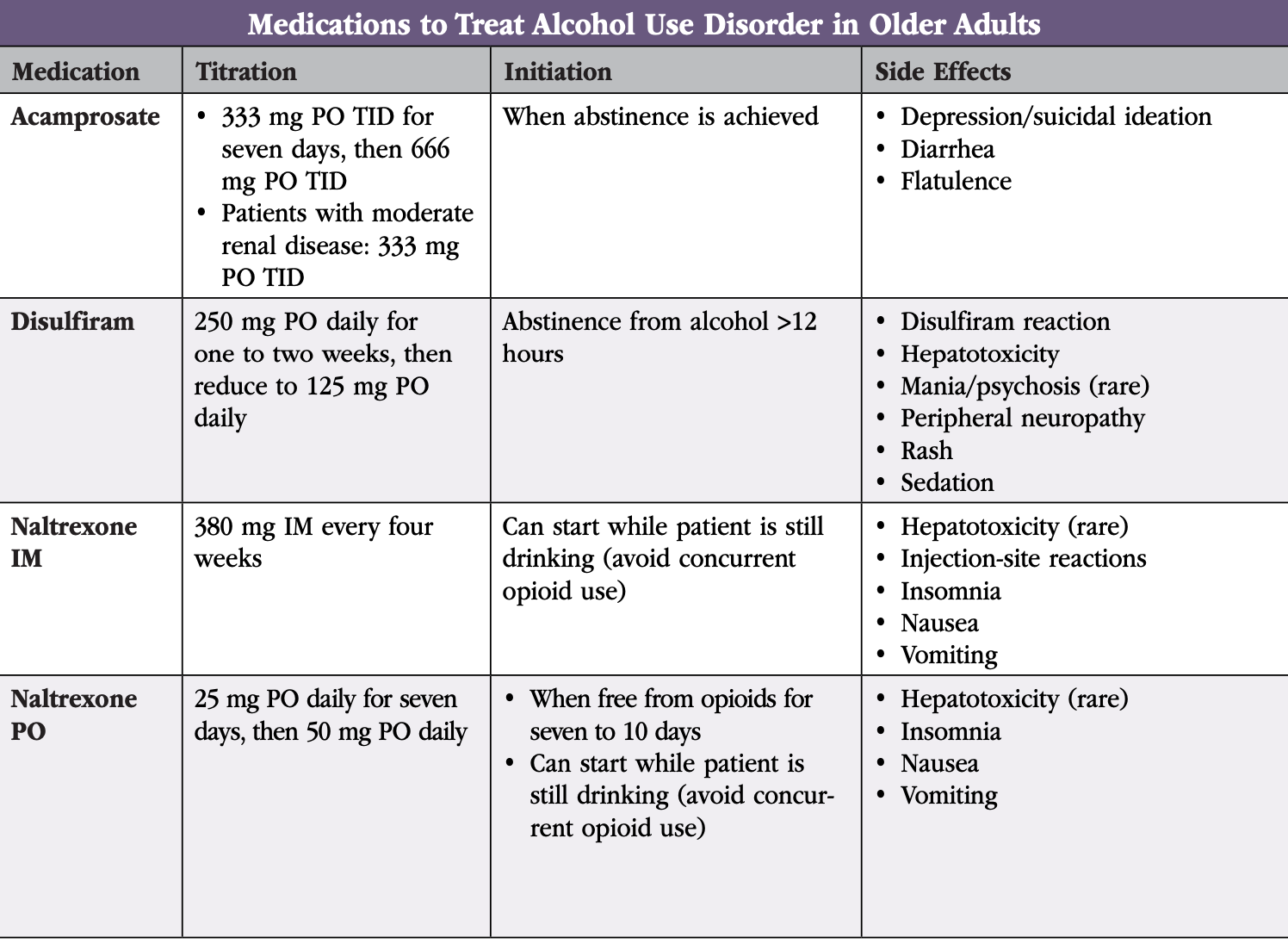

There are three medications approved by the FDA for AUD: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram (see “Medications to Treat Alcohol Use Disorders in Older Adults” table on page 3).

Naltrexone: oral or extended-release injectable (Vivitrol)

Naltrexone is an opioid blocker. It reduces the rewarding effects of alcohol, resulting in fewer drinking days, less heavy drinking, and decreased alcohol cravings. So far, it’s the only MAT studied in older adults (Oslin D et al, Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;5(4):324–332). For most patients, use it as your first-line treatment.

Naltrexone is metabolized through the liver, so exercise caution in patients with liver enzymes greater than five times the upper limit of normal. Rarely, it can also cause liver damage. To monitor for this, check liver function tests at baseline and periodically based on the patient’s medical history (eg, every three months in patients with HCV, HBV, or HIV). Because it blocks opioid receptors, naltrexone may interfere with treatment in patients taking opioids for pain management.

The extended-release (ER) injectable form of naltrexone is administered monthly. It may be ideal for older adults who remain active with work or familial obligations or those who have difficulties with memory. One study of patients with alcohol dependence found that during the first month after injection, patients receiving injectable naltrexone (380 mg IM monthly) had 37% fewer heavy drinking days versus placebo (p<0.01; Ciraulo DA et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(2):190–195). There are no studies examining the efficacy and safety of injectable naltrexone in older adults.

Naltrexone’s most common side effects are nausea and vomiting. The IM form can cause injection-site reactions.

Acamprosate (Campral)

Acamprosate, which may enhance GABA activity, is an attractive option for older adults with AUD. It hasn’t been studied in this population, but in younger adults, acamprosate reduces the risk of returning to drinking and increases the cumulative duration of abstinence (Witkiewitz K et al, Ther Clin Risk Manag 2012;8:45–53). It’s best for patients who have already achieved abstinence. Patients find it reduces their craving for alcohol, decreases anxiety, and helps with insomnia.

Acamprosate is excreted unchanged by the kidneys and, unlike naltrexone, can be prescribed to patients with liver disease. Use it cautiously in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment. Order baseline and follow-up renal function tests only if the patient has evidence of renal impairment. Acamprosate has no known toxic effects and doesn’t interact with other substances. It can be safely prescribed to patients taking other medications. Although clinicians frequently combine naltrexone and acamprosate in younger patients, the combination hasn't been studied in older adults. However, you can consider it when monotherapy is insufficient.

Dosing tips in older adults:

- Acamprosate comes in 333 mg tablets

- Whereas guidelines recommend starting at 666 mg TID, consider starting at 333 mg TID

- If no side effects, increase to 666 mg TID after seven days

Acamprosate’s most common adverse drug reactions are diarrhea and flatulence. The pill burden of two large pills taken three times daily may make it unappealing for some patients.

Disulfiram (Antabuse)

Although disulfiram is usually avoided in older adults, it can be used in healthy older patients who take few medications and are motivated to use it. Disulfiram acts as a deterrent. When someone taking disulfiram drinks alcohol, they develop an aversive physical reaction of nausea, flushing, hypotension, shortness of breath, palpitations, and confusion, which can last for several weeks. In older adults, this reaction can be dangerous.

Disulfiram can also exacerbate heart disease, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, chronic renal failure, and peripheral neuropathy. It can cause liver damage and can interact with a number of medications. It’s especially problematic in patients who have cognitive impairment, lack social support, or live alone.

Dosing tips in older adults (Jacobson SA, Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychopharmacology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014):

- Since disulfiram can be sedating, it’s best taken at bedtime

- Ensure compliance with supervised ingestion by enlisting an accountability partner

Medications for OUD

Medications for OUD

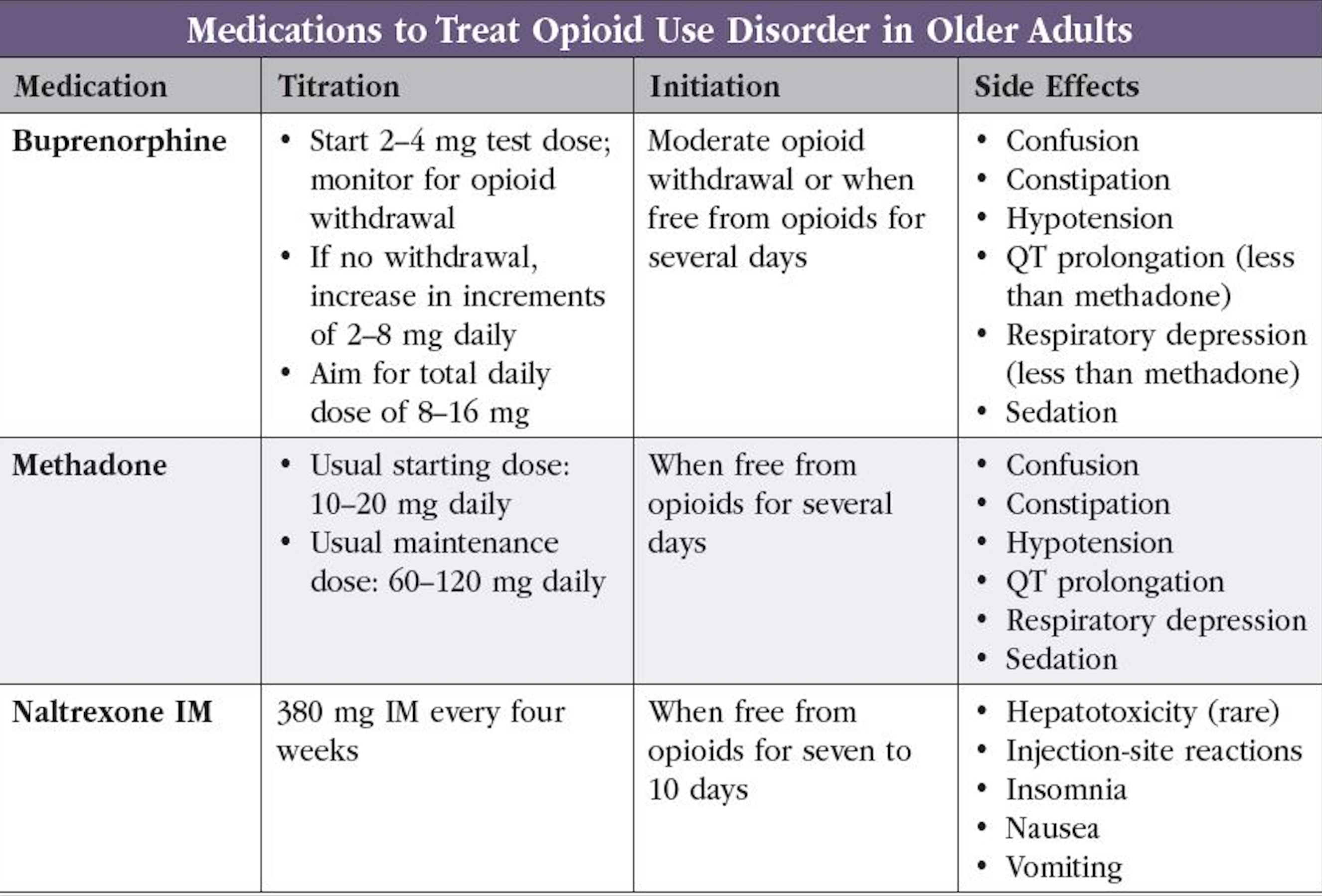

Three medications are FDA approved for OUD: buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone. None of these medications have been studied in older adults (see “Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorders in Older Adults” table on page 3).

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a good first-line treatment in older adults with OUD. It can be prescribed from a clinician’s office, giving patients more flexibility when compared with methadone. It reduces opioid withdrawal symptoms and craving with less risk for euphoria or respiratory depression due to its partial agonist properties. The recent congressional removal of the X waiver requirement eliminates a significant prescribing barrier (Reib LM et al, Can Geriatr J 2020;23(1):123–134; www.tinyurl.com/3zwyc2da).

Buprenorphine is less likely than methadone to interact with other medications, prolong QT intervals, or lead to respiratory depression. As a result, it’s safer in older adults with cardiac and pulmonary disorders. Monitor patients closely for symptoms of sleep apnea, sedation, cognitive impairment, and falls.

Dosing in older adults:

Due to the risk of precipitated withdrawal, never start buprenorphine while a patient has opioids in their system or is in the early withdrawal stages. Start it when a patient has mild to moderate symptoms of withdrawal as measured by the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). Doses for older adults haven’t been worked out, but clinicians can consider:

- Using 25%–50% lower doses

- Increasing doses 25%–50% slower

- Titrating until opioid cravings are suppressed

Guidelines for adults suggest a dosage range of 16–24 mg daily. Some older adults may not tolerate those levels and may do well at doses of 8–16 mg daily (Crotty K et al, J Addict Med 2020;14(2):99–112).

Methadone

Methadone is a full opioid-receptor agonist used to prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms and reduce cravings. It can be more effective than buprenorphine for patients with more severe OUD or higher tolerance to opioid use. Methadone can only be dispensed from federally regulated opioid treatment programs (methadone clinics). This limits its use in older adults without access to transportation or with limited mobility.

Disadvantages of methadone include a greater risk of QT prolongation, sedation, respiratory depression, and falls. As it’s metabolized by CYP3A4 and inhibits CYP2D6, it has many drug-drug interactions. Use it with caution in individuals with hepatic or renal disease. Given its long half-life, the full effects of the dose may not be seen for several days. You can consider methadone maintenance treatment in older adults who aren’t benefitting from or cannot tolerate buprenorphine; however, consider the added risks of oversedation, toxicity, and overdose death (Reib et al, 2020).

Dosing in older adults:

- The methadone clinic will manage initiation and titration

- Collaborate with the clinic for safe prescribing

Naltrexone

Oral naltrexone is FDA approved for the treatment of OUD. However, oral naltrexone is no better than placebo for OUD and, in one direct comparison, was worse than buprenorphine (Le Roux C et al, Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18(9):87). The ER injectable form of naltrexone is preferred; however, it’s a second-line option for older adults with an OUD. Consider it when opioid agonist treatment is contraindicated, unacceptable, unavailable, or discontinued in patients who have a sustained period of abstinence (Dufort A et al, Drugs Aging 2021;38(12):1043–1053).

Naloxone

Older adults are at increased risk for opioid overdose due to their increased sensitivity to sedation/respiratory depression, comorbid medical conditions, and potential drug-drug interactions. Naloxone doesn’t treat OUD or pain, but it can reverse opioid overdose. For all patients receiving MAT, recommend that they purchase naloxone over the counter, or prescribe them an emergency naloxone rescue kit, in case they overdose or are found unresponsive (Le Roux et al, 2016).

CARLAT VERDICT

For most older adults with AUD, start with naltrexone; it's the only medication studied in this population. Acamprosate is a reasonable second option. For OUD, start with buprenorphine and use injectable naltrexone as a backup option.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)