Home » Our Role in Community Disasters

Our Role in Community Disasters

October 30, 2020

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Jess Levy, MD.

Child and adolescent psychiatrist, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, OH.

Dr. Levy has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

A wildfire has broken out near your clinic and is racing through a local neighborhood. Evacuations are underway and thousands are crowding the roads. Reports of several deaths follow shortly and the local Red Cross needs assistance. You want to help out. But how?

School shootings, storms and fires, pandemic, civil unrest—we are faced with unprecedented community suffering outside of what we usually encounter in our practices. This article covers potential roles for assisting your community.

How communities respond to trauma

Whole communities can be subject to acute, chronic, and cumulative trauma. Similar to individuals, communities have distinct risk factors and protective factors, including economic opportunities, leadership, and community attitudes. The 6-phase framework below tracks the emotional response of communities to disasters (Zunin LM and Myers D. Phases of disaster. In DeWolfe DJ, Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000):

Phase 1: Pre-disaster (warnings and threats)

Phase 2: Impact (acute, intense fear)

Phase 3: Heroic (adrenaline-induced rescue activity)

Phase 4: Honeymoon (community cohesion, optimism)

Phase 5: Disillusionment (discouragement, abandonment, exhaustion)

Phase 6: Reconstruction (adjusting to a new normal, recovery)

This framework can help you predict the needs of the community. For example, in response to diminishing COVID-19 numbers, a community in the honeymoon phase might hastily push for resuming schooling without safeguards in place, while a community in the disillusionment phase of the pandemic may see a surge in depression, anxiety, and substance use among its residents.

Leveraging social capital

Social capital is a construct that quantifies the cohesiveness of a community to enable collective action (Flores EC et al, Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018;53(2):107–119). It is defined by shared norms, values, trust, and reciprocity. Communities with high social capital tend to be more vibrant and more socially connected.

The current pandemic highlights how social capital can help a community recover. Research suggests that communities with higher social capital are initially hit with more COVID-19 cases. However, these more cohesive communities have more ability to make voluntary changes and curtail the spread of disease. A European study found that an increase of 1 standard deviation in social capital resulted in up to a 32% reduction in COVID-19 cases (Bartscher AK et al. Social Capital and the Spread of COVID-19: Insights From European Countries. Bonn, Germany: IZA; 2020).

As clinicians, keep this concept in mind and look for ways to support the building and maintenance of social capital in your community. Start by looking at your clinic or practice. For example, work with families to brainstorm ways they can create and nurture social connections using telehealth technology during times when in-person interactions and group events are not safe.

Expanding our roles: Volunteer for deployment

You call your local Red Cross (1-800-RED CROSS; www.redcross.org/volunteer/become-a-volunteer.html) and within 10 days you are credentialed. You are assigned to a shelter where you meet Julia, a 12-year-old girl with no problematic history whose older brother died when they fled the fires. Julia seems to be coping, going through the motions of daily life at the shelter. A social worker assigned to the family helps them obtain short-term housing. You reassure Julia, give guidance to her parents about responses to stress, and offer a free office appointment in six weeks.

You do not need a degree in public health to help a community through a disaster. There are many ways you can help within your scope of practice. While not comprehensive, here’s a list of service/assignment types that may be a good fit for you:

If you’re considering deployment, whether a brief stint or extended time away from your practice, keep in mind the following:

Expanding our roles: Supporting the community from home

Not everyone can leave their practice behind and deploy themselves when a disaster happens. But there are a number of things almost any clinician can do that are very helpful.

Support other clinicians or responders who are volunteering

Offer backup coverage for psychiatrists who are deployed. Volunteer time for organizations that provide disaster recovery assistance—for example, you could provide an hour of pro bono care every week. Start with your local professional society (AACAP, APA chapter, or county medical society).

Assist your community with disaster preparedness

As respected members of the community, we have much to offer through civic engagement. Many communities have disaster response teams—check with your local government. Consider completing a Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) training program. This free course teaches laypeople how to assist first responders in a disaster (www.ready.gov/cert).

Be a pediatric mental health liaison

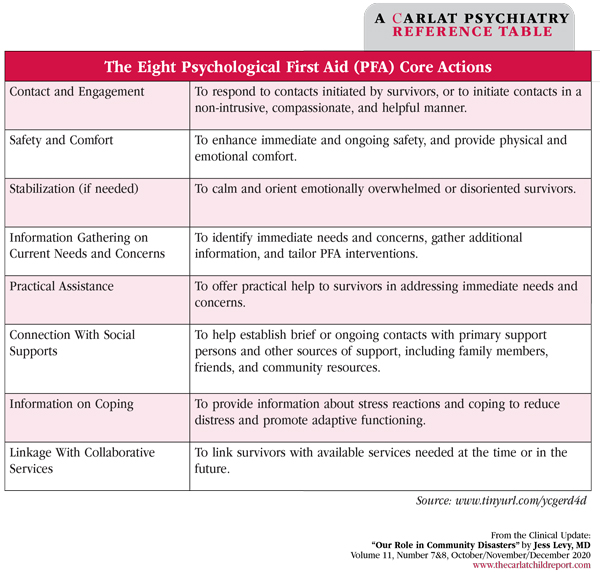

When communicating with schools, colleagues, and others in your clinical practice, offer talks, interviews, or podcasts to educators, parents, first responders, and health providers about the biological, psychological, and social impacts of crisis on youth. AACAP provides training opportunities and resources for families (www.tinyurl.com/y8nmqs66). You can also enroll in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) Psychological First Aid (PFA) course. It’s quick and inexpensive, and you will learn how to assist survivors and the relief community. See the table below for core actions in PFA (www.nctsn.org).

CCPR Verdict: Our unique expertise affords us meaningful opportunities to help our communities during crises. First and foremost, though, we must take care of our patients while taking care of ourselves.

Child PsychiatrySchool shootings, storms and fires, pandemic, civil unrest—we are faced with unprecedented community suffering outside of what we usually encounter in our practices. This article covers potential roles for assisting your community.

How communities respond to trauma

Whole communities can be subject to acute, chronic, and cumulative trauma. Similar to individuals, communities have distinct risk factors and protective factors, including economic opportunities, leadership, and community attitudes. The 6-phase framework below tracks the emotional response of communities to disasters (Zunin LM and Myers D. Phases of disaster. In DeWolfe DJ, Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000):

Phase 1: Pre-disaster (warnings and threats)

Phase 2: Impact (acute, intense fear)

Phase 3: Heroic (adrenaline-induced rescue activity)

Phase 4: Honeymoon (community cohesion, optimism)

Phase 5: Disillusionment (discouragement, abandonment, exhaustion)

Phase 6: Reconstruction (adjusting to a new normal, recovery)

This framework can help you predict the needs of the community. For example, in response to diminishing COVID-19 numbers, a community in the honeymoon phase might hastily push for resuming schooling without safeguards in place, while a community in the disillusionment phase of the pandemic may see a surge in depression, anxiety, and substance use among its residents.

Leveraging social capital

Social capital is a construct that quantifies the cohesiveness of a community to enable collective action (Flores EC et al, Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018;53(2):107–119). It is defined by shared norms, values, trust, and reciprocity. Communities with high social capital tend to be more vibrant and more socially connected.

The current pandemic highlights how social capital can help a community recover. Research suggests that communities with higher social capital are initially hit with more COVID-19 cases. However, these more cohesive communities have more ability to make voluntary changes and curtail the spread of disease. A European study found that an increase of 1 standard deviation in social capital resulted in up to a 32% reduction in COVID-19 cases (Bartscher AK et al. Social Capital and the Spread of COVID-19: Insights From European Countries. Bonn, Germany: IZA; 2020).

As clinicians, keep this concept in mind and look for ways to support the building and maintenance of social capital in your community. Start by looking at your clinic or practice. For example, work with families to brainstorm ways they can create and nurture social connections using telehealth technology during times when in-person interactions and group events are not safe.

Expanding our roles: Volunteer for deployment

You call your local Red Cross (1-800-RED CROSS; www.redcross.org/volunteer/become-a-volunteer.html) and within 10 days you are credentialed. You are assigned to a shelter where you meet Julia, a 12-year-old girl with no problematic history whose older brother died when they fled the fires. Julia seems to be coping, going through the motions of daily life at the shelter. A social worker assigned to the family helps them obtain short-term housing. You reassure Julia, give guidance to her parents about responses to stress, and offer a free office appointment in six weeks.

You do not need a degree in public health to help a community through a disaster. There are many ways you can help within your scope of practice. While not comprehensive, here’s a list of service/assignment types that may be a good fit for you:

- Offer free office hours for children impacted by disasters. This might be the simplest way to help out. Contact referral sources such as the Red Cross to let them know that you are available (www.redcross.org/volunteer/volunteer-opportunities/disaster-volunteer.html).

- Provide care at shelters. Shelters are in need of clinicians to work with staff and other professionals to assess and treat displaced children and families.

- Advise disaster workers on supportive care. Coach first responders and other frontline personnel about how to best help children and families, emphasizing developmental differences in response to disasters.

- Provide supportive listening. Have in-person or virtual conversations with everyone from community leaders to first responders; offer referrals for definitive care when indicated.

- Assist with media work. As clinicians, we can have a positive impact on civil calm and self-care. Training is critical, however, as missteps with such things as patient confidentiality or community advice can amplify problems. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) offers a media training course for disaster and trauma as part of their annual meetings

- (www.AACAP.org).

If you’re considering deployment, whether a brief stint or extended time away from your practice, keep in mind the following:

- Never self-deploy. Showing up on your own to a disaster zone creates confusion and hinders the response process. Instead, volunteer through organizations such as the Red Cross. The American Medical Association has a listing of volunteer needs related to COVID-19 (www.tinyurl.com/yxlgza7x).

- Be the psychiatrist, not the primary care clinician. Federal and state laws protect volunteer health providers from medical liability, but the standard of care still applies. For instance, if you treat someone for hypertension “because it’s faster than waiting for the general internist,” you will be held to the usual community standard in doing so.

- Take care of your own health. Do not try to operate on little sleep, stay hydrated, and do not skip meals (Ng AT, Psychiatric Times 2010;27:11). Don’t become a casualty; follow direction of first responders in regard to safety.

Expanding our roles: Supporting the community from home

Not everyone can leave their practice behind and deploy themselves when a disaster happens. But there are a number of things almost any clinician can do that are very helpful.

Support other clinicians or responders who are volunteering

Offer backup coverage for psychiatrists who are deployed. Volunteer time for organizations that provide disaster recovery assistance—for example, you could provide an hour of pro bono care every week. Start with your local professional society (AACAP, APA chapter, or county medical society).

Assist your community with disaster preparedness

As respected members of the community, we have much to offer through civic engagement. Many communities have disaster response teams—check with your local government. Consider completing a Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) training program. This free course teaches laypeople how to assist first responders in a disaster (www.ready.gov/cert).

Be a pediatric mental health liaison

When communicating with schools, colleagues, and others in your clinical practice, offer talks, interviews, or podcasts to educators, parents, first responders, and health providers about the biological, psychological, and social impacts of crisis on youth. AACAP provides training opportunities and resources for families (www.tinyurl.com/y8nmqs66). You can also enroll in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) Psychological First Aid (PFA) course. It’s quick and inexpensive, and you will learn how to assist survivors and the relief community. See the table below for core actions in PFA (www.nctsn.org).

CCPR Verdict: Our unique expertise affords us meaningful opportunities to help our communities during crises. First and foremost, though, we must take care of our patients while taking care of ourselves.

Table: The Eight Psychological First Aid (PFA) Core Actions

(Click to view as full-size PDF.)

Issue Date: October 30, 2020

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)