Depression, Vitamin D, and COVID-19

Your patient with a history of depression comes to see you with a magazine article in hand. She has read that vitamin D deficiency causes depression and wants to know if she can get hers checked.

Based on what we already know about this patient, there’s a good chance her levels are low. In the US, 1 in 4 people have low vitamin D levels, and the rate is even higher among psychiatric patients. Up to 1 in 3 persons with depression and 3 in 5 persons with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia have vitamin D levels < 20 ng/mL (Boerman R et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36(6):588–592). But is it worth checking? And will supplementation help this patient’s mood? In this article we’ll review the research on vitamin D and depression, as well as its role in general health and COVID-19.

Vitamin D and psychiatric disorders

First, some basics. Vitamin D’s main function is to help us absorb calcium, which is necessary for bone strength. We can maintain our stores of vitamin D in two ways: by taking supplements or exposing ourselves to natural sunlight for at least 15 minutes three times per week. Long-term vitamin D deficiency causes a range of health problems, including low birth weight, rickets, fractures, and possibly even cancer, cardiovascular disease, and death (Theodoratou E et al, BMJ 2014;348:g2035). More controversial is whether less extreme deficiencies (“insufficiencies”) of vitamin D can cause more subtle problems with energy or mood.

Epidemiological studies of variable quality show that low levels of vitamin D are associated with the development of autism, schizophrenia, seasonal affective disorder, and depression—although the evidence is very weak for autism and seasonal affective disorder. For schizophrenia, one high-quality case control study with 3,464 participants showed that the risk of developing schizophrenia was 44% higher among neonates with the lowest levels of vitamin D (< 8 ng/mL) compared to those with levels between 16 and 21 ng/mL (Eyles DW et al, Scientific Reports 2018;8:1–8).

For depression, one important meta-analysis from 2013 showed participants with the lowest levels of vitamin D had a 30% increased odds of developing depression, although this was not quite statistically significant (OR 1.31 [95% CI: 1.0–1.71] (Anglin RES et al, Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:100–107). But since our vitamin D stores are largely made by exposure to sunlight, all of these epidemiologic studies are confounded by the possibility that vitamin D levels may reflect lifestyle choices. In other words, it’s possible that people with mental illness are more likely to spend more time indoors—which would cause low vitamin D levels. Low vitamin D may be the result of depression rather than the cause.But what about treatment? For that, we turn to randomized controlled trials. Nearly all are in depression, and the results are mixed.

First, supplementing vitamin D in healthy persons without depression does not prevent the development or recurrence of depression (Okereke OI et al, JAMA 2020;324(5):471–480). Supplementation is also not helpful for depressed individuals who do not have vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency (Menon et al, 2020). It may, however, be helpful as an adjunct treatment for persons with clinical depression and with levels < 20 ng/mL. There are two positive and two negative randomized controlled trials, with various flaws on both sides, from small sample size to lack of blinding (Menon et al, 2020).Overall, the best we can say is that little harm seemed to occur from supplementation, with only 5 of 362 participants who received high-dose vitamin D stopping the vitamin due to side effects (Wang Y et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36(3):229–235). For bipolar disorder, the evidence for supplementation is even weaker, with one tiny positive trial (n = 16) and one slightly larger negative trial (n = 33) (Cereda G et al, J Affect Disord 2021;278(1):209–217).

Low vitamin D and COVID-19What conditions remain where vitamin D supplementation may be helpful? While low vitamin D has been linked to multiple health problems, clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation for most of these conditions have also been disappointing (Bolland MJ et al, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6(11):847–858).

Many people are supplementing with vitamin D to prevent COVID-19 infection, and there is some logic behind that if their levels are low. There is strong evidence that vitamin D helps prevent respiratory tract infections. A recent meta-analysis suggested a 9% reduction in the likelihood of experiencing at least one acute respiratory infection (Jolliffe DA et al, medRxiv 2020 [preprint]; PMID: 33269357).

Current studies on vitamin D and COVID-19 are limited but intriguing. In the only randomized controlled trial on vitamin D supplementation in COVID-19 patients, only 2% of the patients in the vitamin D3 group required admission to the ICU compared to 50% of the patients in the placebo group (Castillo ME et al, J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2020;203:105751). That sounds impressive, but the study was small (n = 76) and the randomization imperfect (there were more patients with diabetes—which itself worsens COVID-19 prognosis—in the placebo group).Balance is key

We have some evidence that treating vitamin D deficiency may be good for physical and mental health, but what if we go too far? Several observational studies suggest that there is a point where high levels of vitamin D increase the risks of respiratory infection, cancer, and death. In terms of mortality, the sweet spot appears to be between 20 and 40 ng/mL, according to one large cohort study of nearly 250,000 individuals (Durup D et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97(8):2644–2652). These studies support the recommendations by the Institute of Medicine to define vitamin D deficiency as < 12 ng/mL and insufficiency as < 20 ng/mL.

Labs and treatment

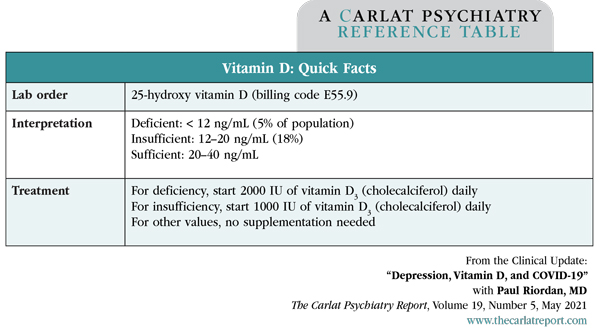

Vitamin D is worthwhile to check when screening for causes of psychiatric disorders. However, given the uncertainties in the benefits and possible risks of over-supplementation, I would only start treatment when a patient’s levels are clearly low (< 20 ng/mL; see Quick Facts table for dosing). Recheck labs 3–4 months after starting treatment, and stop treatment once stores are adequate (> 30 ng/mL). If risk factors for low vitamin D remain (indoor living, poor diet, depression), recheck levels about 6 months after stopping supplementation.

Table: Vitamin D: Quick Facts

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

![]() To learn more, listen to our 5/24/21 podcast, “How COVID Affects the Brain.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

To learn more, listen to our 5/24/21 podcast, “How COVID Affects the Brain.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)