Home » Battle of the Bulge: Obesity and Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain

Battle of the Bulge: Obesity and Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain

July 14, 2021

From The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report

Farah Khorassani, PharmD. Clinical Assistant

Professor of Pharmacy Practice, St. John’s University, Queens, NY.

Dr. Khorassani has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Many psychiatric medications cause weight gain, including mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and especially antipsychotics. Most weight gain secondary to antipsychotic use occurs in the first 6 months of therapy, so it’s important to monitor weight closely and intervene early in a patient’s treatment. We counsel patients at every visit about healthy diets, portion control, and regular exercise. This article offers practical pharmacologic strategies for the prevention and treatment of obesity and antipsychotic-induced weight gain (AIWG).

Prevention, switch, and augmentation strategies

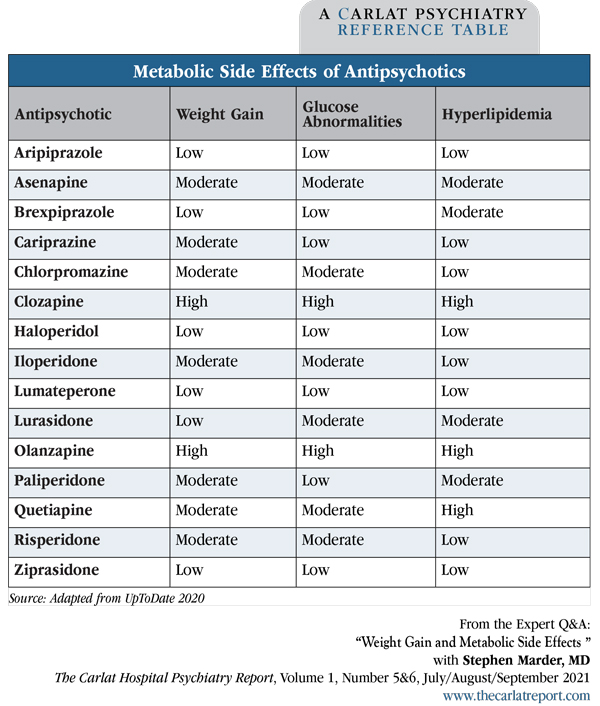

The cornerstone of preventing AIWG is antipsychotic selection. Atypical antipsychotics with a low metabolic risk, including aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone, and ziprasidone, will minimize weight gain (Musil R et al, Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015;14(1):73–96). Some first-generation agents, like haloperidol, are also less likely to cause metabolic syndrome (Editor’s note: See “Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics” table, below).

If patients have gained weight on other antipsychotics, can they lose weight by switching to agents with a low metabolic risk? Probably so, at least for aripiprazole, which is the only agent that’s been studied in this manner. In a 24-week study of 206 overweight patients who were randomized to continue on olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone or to switch to aripiprazole, patients who switched to aripiprazole experienced significantly greater weight reduction (3.7 kg) compared to patients who continued on their previous medications (0.7 kg) (Stroup TS et al, Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(9):947–956). The study included a diet and exercise program for all subjects.

If changing from an antipsychotic with high metabolic risk is not feasible, augmenting the antipsychotic with low or medium doses of aripiprazole (5–15 mg/day) can help. This strategy stood out as the most effective pharmacologic intervention in a recent comprehensive meta-analysis (Vancampfort D et al, World Psychiatry 2019;18(1):53–66).

Pharmacologic treatment of AIWG

Metformin

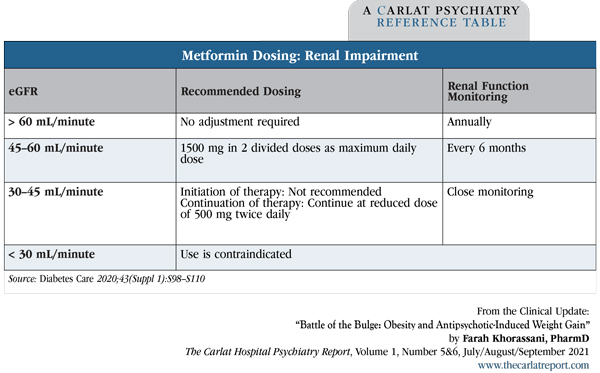

Metformin (Glucophage) (500–1000 mg twice daily) is the best-studied and most widely used medication to treat AIWG. It produces a weight loss, on average, of about 3 kg (de Silva VA et al, BMC Psychiatry 2016;16(1):341) or about a 3% reduction in body weight, compared to a 1% reduction with placebo (Jarskog LF et al, Am J Psychiatry 2013;170(9):1032–1040). While this is not as much weight loss as seen with other agents, metformin is well tolerated and safe, and it helps treat insulin resistance—an additional benefit, given that many of our patients are diabetic or prediabetic. Nausea and diarrhea occur in 25%–50% of patients early in treatment; these side effects are minimized by taking metformin with food or using the extended-release formulation. Patients must be screened for liver or kidney impairment as both increase the risk of lactic acidosis in patients on this medication. If a patient’s eGFR is less than 60 mL/minute, adjust the dosing.

Should we start metformin prophylactically to prevent AIWG? This question has not been well studied, but research generally supports this practice. For example, a 12-week study of patients randomized to olanzapine 15 mg plus metformin 750 mg (n = 20), vs olanzapine 15 mg plus placebo (n = 20), found that the 63% of patients taking olanzapine + placebo increased their weight by more than 7% vs only 17% of patients taking olanzapine + metformin (Wu RR et al, Am J Psychiatry 2008;165(3):352–358). A randomized controlled trial is currently underway evaluating prophylactic metformin for patients starting clozapine (Siskind D et al, BMJ Open 2018;8(3):e021000).

Topiramate (Topamax)

Topiramate (50–400 mg per day) produces more weight loss than metformin, averaging about 4 kg (Goh KK et al, Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2019;23(1):14–32). However, about 30% of patients—especially those at higher doses—experience cognitive impairments, including problems with memory and attention (a reason it is jokingly referred to as “Dopamax”). Monitor vision because of the increased risk of angle-closure glaucoma. Additionally, use caution when prescribing topiramate to pregnant women (increased risk of cleft palate) and to women on birth control pills (topiramate induces the metabolism of estrogen and can diminish the efficacy of the contraceptive).

Olanzapine/samidorphan

We will soon have a new treatment option to mitigate olanzapine-induced weight gain: a combination of olanzapine with samidorphan, an opioid receptor antagonist. In a recent study that compared weight changes in patients receiving this combination to patients receiving olanzapine alone, weight increased 4.2% in the olanzapine/samidorphan group compared to 6.6% in the olanzapine monotherapy group (Correll CU et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(12):1168–1178). The FDA approved this combined olanzapine-samidorphan formulation (Lybalvi) on June 1, 2021 (Editor’s note: See the Research Update that covers AIWG for more information).

Other weight loss medications to consider

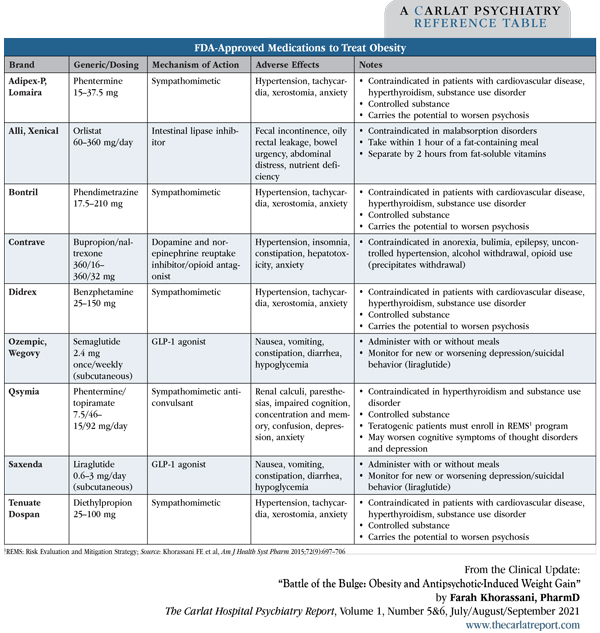

Numerous medications are on the market for weight loss (Editor’s note: See “FDA-Approved Medications to Treat Obesity” table below). The list used to be longer, but two medications—sibutramine (Meridia) and lorcaserin (Belviq)—were recently withdrawn due to elevated risks of cardiovascular events and cancer, respectively. Selection is determined by side effect profiles, cost, insurance coverage, method of administration (oral vs subcutaneous), and estimated length of treatment, as some medications have only been approved for short-term use. With the exception of liraglutide, these medications have been studied for obesity, but not for obesity secondary to antipsychotic drug use.

Orlistat (Xenical)

Orlistat inhibits the action of lipase in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby preventing the breakdown and absorption of fats through the small intestine. Compared to other medications for obesity, orlistat produces the least weight loss (2.6 kg) (Khera R et al, JAMA 2016;315(22):2424–2434). Further, orlistat’s primary side effects are diarrhea and fatty stools over the first 4 weeks. It’s dosed at 120 mg TID with meals, and patients should take vitamin supplements to ensure they get their daily A, D, E, and K. Orlistat has the advantage of being available over the counter in a lower-dose called Alli.

Liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda)

Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist (GLP-1 agonist) that lowers blood sugar and weight by decreasing both glucose production and appetite and by increasing insulin sensitivity. Of all the weight loss agents, it produces the greatest average weight loss (5.2 kg) compared to placebo (Khera et al, 2016). Liraglutide is FDA approved for type II diabetes as well as for obesity and appears effective for AIWG: A study of patients (n = 97) taking clozapine or olanzapine who were randomized to add-on treatment with either liraglutide (1.2–1.8 mg daily) or placebo found that those in the liraglutide group lost an average of 4.7 kg compared to a gain of 0.5 kg in the placebo group (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728). There are some serious trade-offs, though: Liraglutide is administered subcutaneously, and it causes nausea in about two-thirds of patients.

Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy)

Semaglutide is another GLP-1 agonist that has been in the news lately due to its reported efficacy as a weight loss agent. A recent study randomized non-diabetic patients with a BMI of 30 or more (n = 1961) to once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo, plus lifestyle intervention (Wilding JPH et al, N Engl J Med 2021;384(11):989). After 68 weeks, patients in the semaglutide group lost an average of 15% of their baseline body weight, or 33.7 pounds, compared to 2.4%, or 5.7 pounds, in the placebo group. The weight loss began early in treatment: Patients on semaglutide experienced more than a 2% reduction in body weight within the first 4 weeks. Side effects consisted primarily of transient nausea and diarrhea. In June 2021, the FDA approved semaglutide for weight loss (in addition to its indication for type 2 diabetes).

Sympathomimetics

Medications like phentermine (Adipex-P, Lomaira) are effective in inducing weight loss but have only been approved for short-term obesity management (ie, a few months). Watch for new onset of psychosis when patients take these agents. They are not good choices for patients with substance use disorders because of their abuse potential, or for patients with primary psychotic disorders.

Co-formulated agents

Phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia) and bupropion/naltrexone (Contrave) are substantially more effective than these medications taken alone, so they are marketed as combination tablets. Qsymia produces 8%–10% reduction in weight vs about 1% with placebo (Gadde KM et al, Lancet 2011;377(9774):1341–1352). Similarly, Contrave leads to 5%–6% reduction in weight vs 1% with placebo (Greenway FL et al, Lancet 2010;376(9741):595–605).

While these findings appear promising, we need to be cautious when prescribing Qsymia or Contrave in certain populations. Avoid bupropion in patients with eating or seizure disorders, avoid naltrexone in opioid users and patients with liver dysfunction, and use caution when prescribing topiramate to pregnant women or women on birth control pills.

CHPR Verdict: There are several options for treating AIWG—though none are likely to yield spectacular weight loss. Metformin (Glucophage) and topiramate (Topamax) are commonly used and relatively safe. Liraglutide also helps, but many patients don’t want to use injectable medications. A new kid on the block, olanzapine/samidorphan, looks promising if it gains FDA approval. In addition, there are many other meds designed for general weight loss that have not been studied for AIWG but may be worth trying in select patients.

Hospital PsychiatryPrevention, switch, and augmentation strategies

The cornerstone of preventing AIWG is antipsychotic selection. Atypical antipsychotics with a low metabolic risk, including aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone, and ziprasidone, will minimize weight gain (Musil R et al, Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015;14(1):73–96). Some first-generation agents, like haloperidol, are also less likely to cause metabolic syndrome (Editor’s note: See “Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics” table, below).

Table: Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

If patients have gained weight on other antipsychotics, can they lose weight by switching to agents with a low metabolic risk? Probably so, at least for aripiprazole, which is the only agent that’s been studied in this manner. In a 24-week study of 206 overweight patients who were randomized to continue on olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone or to switch to aripiprazole, patients who switched to aripiprazole experienced significantly greater weight reduction (3.7 kg) compared to patients who continued on their previous medications (0.7 kg) (Stroup TS et al, Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(9):947–956). The study included a diet and exercise program for all subjects.

If changing from an antipsychotic with high metabolic risk is not feasible, augmenting the antipsychotic with low or medium doses of aripiprazole (5–15 mg/day) can help. This strategy stood out as the most effective pharmacologic intervention in a recent comprehensive meta-analysis (Vancampfort D et al, World Psychiatry 2019;18(1):53–66).

Pharmacologic treatment of AIWG

Metformin

Metformin (Glucophage) (500–1000 mg twice daily) is the best-studied and most widely used medication to treat AIWG. It produces a weight loss, on average, of about 3 kg (de Silva VA et al, BMC Psychiatry 2016;16(1):341) or about a 3% reduction in body weight, compared to a 1% reduction with placebo (Jarskog LF et al, Am J Psychiatry 2013;170(9):1032–1040). While this is not as much weight loss as seen with other agents, metformin is well tolerated and safe, and it helps treat insulin resistance—an additional benefit, given that many of our patients are diabetic or prediabetic. Nausea and diarrhea occur in 25%–50% of patients early in treatment; these side effects are minimized by taking metformin with food or using the extended-release formulation. Patients must be screened for liver or kidney impairment as both increase the risk of lactic acidosis in patients on this medication. If a patient’s eGFR is less than 60 mL/minute, adjust the dosing.

Table: Metformin Dosing: Renal Impairment

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

Should we start metformin prophylactically to prevent AIWG? This question has not been well studied, but research generally supports this practice. For example, a 12-week study of patients randomized to olanzapine 15 mg plus metformin 750 mg (n = 20), vs olanzapine 15 mg plus placebo (n = 20), found that the 63% of patients taking olanzapine + placebo increased their weight by more than 7% vs only 17% of patients taking olanzapine + metformin (Wu RR et al, Am J Psychiatry 2008;165(3):352–358). A randomized controlled trial is currently underway evaluating prophylactic metformin for patients starting clozapine (Siskind D et al, BMJ Open 2018;8(3):e021000).

Topiramate (Topamax)

Topiramate (50–400 mg per day) produces more weight loss than metformin, averaging about 4 kg (Goh KK et al, Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2019;23(1):14–32). However, about 30% of patients—especially those at higher doses—experience cognitive impairments, including problems with memory and attention (a reason it is jokingly referred to as “Dopamax”). Monitor vision because of the increased risk of angle-closure glaucoma. Additionally, use caution when prescribing topiramate to pregnant women (increased risk of cleft palate) and to women on birth control pills (topiramate induces the metabolism of estrogen and can diminish the efficacy of the contraceptive).

Olanzapine/samidorphan

We will soon have a new treatment option to mitigate olanzapine-induced weight gain: a combination of olanzapine with samidorphan, an opioid receptor antagonist. In a recent study that compared weight changes in patients receiving this combination to patients receiving olanzapine alone, weight increased 4.2% in the olanzapine/samidorphan group compared to 6.6% in the olanzapine monotherapy group (Correll CU et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(12):1168–1178). The FDA approved this combined olanzapine-samidorphan formulation (Lybalvi) on June 1, 2021 (Editor’s note: See the Research Update that covers AIWG for more information).

Other weight loss medications to consider

Numerous medications are on the market for weight loss (Editor’s note: See “FDA-Approved Medications to Treat Obesity” table below). The list used to be longer, but two medications—sibutramine (Meridia) and lorcaserin (Belviq)—were recently withdrawn due to elevated risks of cardiovascular events and cancer, respectively. Selection is determined by side effect profiles, cost, insurance coverage, method of administration (oral vs subcutaneous), and estimated length of treatment, as some medications have only been approved for short-term use. With the exception of liraglutide, these medications have been studied for obesity, but not for obesity secondary to antipsychotic drug use.

Orlistat (Xenical)

Orlistat inhibits the action of lipase in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby preventing the breakdown and absorption of fats through the small intestine. Compared to other medications for obesity, orlistat produces the least weight loss (2.6 kg) (Khera R et al, JAMA 2016;315(22):2424–2434). Further, orlistat’s primary side effects are diarrhea and fatty stools over the first 4 weeks. It’s dosed at 120 mg TID with meals, and patients should take vitamin supplements to ensure they get their daily A, D, E, and K. Orlistat has the advantage of being available over the counter in a lower-dose called Alli.

Liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda)

Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist (GLP-1 agonist) that lowers blood sugar and weight by decreasing both glucose production and appetite and by increasing insulin sensitivity. Of all the weight loss agents, it produces the greatest average weight loss (5.2 kg) compared to placebo (Khera et al, 2016). Liraglutide is FDA approved for type II diabetes as well as for obesity and appears effective for AIWG: A study of patients (n = 97) taking clozapine or olanzapine who were randomized to add-on treatment with either liraglutide (1.2–1.8 mg daily) or placebo found that those in the liraglutide group lost an average of 4.7 kg compared to a gain of 0.5 kg in the placebo group (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728). There are some serious trade-offs, though: Liraglutide is administered subcutaneously, and it causes nausea in about two-thirds of patients.

Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy)

Semaglutide is another GLP-1 agonist that has been in the news lately due to its reported efficacy as a weight loss agent. A recent study randomized non-diabetic patients with a BMI of 30 or more (n = 1961) to once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo, plus lifestyle intervention (Wilding JPH et al, N Engl J Med 2021;384(11):989). After 68 weeks, patients in the semaglutide group lost an average of 15% of their baseline body weight, or 33.7 pounds, compared to 2.4%, or 5.7 pounds, in the placebo group. The weight loss began early in treatment: Patients on semaglutide experienced more than a 2% reduction in body weight within the first 4 weeks. Side effects consisted primarily of transient nausea and diarrhea. In June 2021, the FDA approved semaglutide for weight loss (in addition to its indication for type 2 diabetes).

Sympathomimetics

Medications like phentermine (Adipex-P, Lomaira) are effective in inducing weight loss but have only been approved for short-term obesity management (ie, a few months). Watch for new onset of psychosis when patients take these agents. They are not good choices for patients with substance use disorders because of their abuse potential, or for patients with primary psychotic disorders.

Co-formulated agents

Phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia) and bupropion/naltrexone (Contrave) are substantially more effective than these medications taken alone, so they are marketed as combination tablets. Qsymia produces 8%–10% reduction in weight vs about 1% with placebo (Gadde KM et al, Lancet 2011;377(9774):1341–1352). Similarly, Contrave leads to 5%–6% reduction in weight vs 1% with placebo (Greenway FL et al, Lancet 2010;376(9741):595–605).

While these findings appear promising, we need to be cautious when prescribing Qsymia or Contrave in certain populations. Avoid bupropion in patients with eating or seizure disorders, avoid naltrexone in opioid users and patients with liver dysfunction, and use caution when prescribing topiramate to pregnant women or women on birth control pills.

CHPR Verdict: There are several options for treating AIWG—though none are likely to yield spectacular weight loss. Metformin (Glucophage) and topiramate (Topamax) are commonly used and relatively safe. Liraglutide also helps, but many patients don’t want to use injectable medications. A new kid on the block, olanzapine/samidorphan, looks promising if it gains FDA approval. In addition, there are many other meds designed for general weight loss that have not been studied for AIWG but may be worth trying in select patients.

Table: FDA-Approved Medications to Treat Obesity

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

KEYWORDS aripiprazole benzphetamine bupropion diabetes diethylpropion exercise insulin-resistance liraglutide metabolic-syndrome metformin naltrexone olanzapine phendimetrazine phentermine samidorphan semaglutide side-effects topiramate waist-circumference weight-gain ziprasidone

Issue Date: July 14, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)