Home » Anticholinergic Drugs and Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

Anticholinergic Drugs and Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

September 13, 2021

From The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report

Shelly L. Gray, PharmD

Shelly L. Gray, PharmD

Professor and Plein Endowed Director, Plein Center for Geriatric Pharmacy Research, School of Pharmacy, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Dr. Gray has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CHPR: Can you tell us about your research?

Dr. Gray: My research uses large databases to examine medication safety issues in older adults with the goal of optimizing healthy aging. My focus is on examining medications and risk for dementia, falls, and fractures—the types of outcomes that are not easily addressed in randomized controlled trials.

CHPR: And in your research on medications and risk for dementia, you have found that anticholinergic medications are associated with an increased risk.

Dr. Gray: Exactly. We conducted a study of older adult subjects who did not have a dementia diagnosis at study entry and found that those with higher cumulative exposure to anticholinergic agents were significantly more likely to receive this diagnosis after, on average, seven years (Gray SL et al, JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(3):401–407).

CHPR: Have other studies had similar findings?

Dr. Gray: Yes. To give a couple of examples, a case-control study of over 40,000 older adult patients reported that certain classes of anticholinergic medications were strongly associated with higher risk of new-onset dementia (Richardson K et al, BMJ 2018;361:k1315). Another study, which looked at nearly 300,000 subjects age 55 and above, found a nearly 50% increased risk of dementia associated with three years of daily use of strong anticholinergic medications (Coupland CAC et al, JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(8):1084–1093).

CHPR: How much should these studies worry us? After all, for years we thought benzodiazepines increased the risk for dementia, but new data show they don’t seem to increase this risk.

Dr. Gray: Right. The results of recent research using high-quality study designs do not support a link between benzodiazepines and dementia (Espinoza RT, J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21(2):143–145). There are a lot of issues that can complicate these pharmacoepidemiology studies—and that’s true for studies that have examined anticholinergics too.

CHPR: Can you say more on the limitations of pharmacoepidemiology studies?

Dr. Gray: Sure. These studies rely on pharmacy prescription fills, and patients don’t always adhere to their prescribed medications. Patients may take over-the-counter meds that aren’t included in studies’ analyses, and they may inaccurately estimate their alcohol and nicotine use. Protopathic bias is another important concern.

CHPR: What is protopathic bias?

Dr. Gray: It occurs when a drug is used to treat early symptoms of a disease that has not yet been diagnosed. Patients take benzodiazepines and anticholinergics in the years leading up to a dementia diagnosis for treatment of prodromal symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia. If researchers don’t take this use into account, their studies will show spurious positive associations.

CHPR: When research takes these limitations and biases into account, do studies still show a strong association between anticholinergic drugs and dementia?

Dr. Gray: Yes. We can’t 100% rule out that biases are not an issue, but several studies have done a good job addressing these issues.

CHPR: Is the research consistent in finding a link between anticholinergics and cognitive impairment?

Dr. Gray: There are some discrepancies in the research. For example, in a study I mentioned earlier, the risk of cognitive impairment was linked with anticholinergic antidepressant, urological, and antiparkinsonian drugs, but not gastrointestinal medications (Richardson et al, 2018). But as a whole, the literature supports an association.

CHPR: We know that acetylcholine is important for memory and learning, so it’s reasonable to worry that medications that reduce cholinergic activity might adversely affect cognition.

Dr. Gray: Right, and the main drugs approved for dementia are cholinesterase inhibitors, which increase levels of acetylcholine.

CHPR: If cognitive impairment is directly linked to anticholinergic medications, is the impairment reversible once these medications are stopped?

Dr. Gray: Unfortunately, this question hasn’t received a lot of attention. A study of older adults who were followed over four years reported that the risk of cognitive decline was about 1.5–2 times higher for continuous anticholinergic users but not for those who discontinued the medications (Carrière I et al, Arch Intern Med 2009;169(14):1317–1324). That’s reassuring—but in my study (Gray et al, 2015), we found the dementia risk was similar among people with past heavy use of anticholinergics and people with recent heavy use, suggesting that the risk for dementia with anticholinergic use persists despite discontinuation.

CHPR: It sounds like most research on anticholinergic agents and cognitive impairment has focused on older adults.

Dr. Gray: Yes, since older patients are at greater risk for cognitive decline and are more prone to side effects. However, we also have limited evidence linking anticholinergic exposure with deteriorating cognition in younger patients. More studies with better methods are needed to determine the risks in younger people.

CHPR: And even in subjects younger than age 50. I read a recent study that looked at the relationship between anticholinergic medication exposure and cognitive performance in patients as young as age 18 with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and found that higher anticholinergic burden was significantly associated with worse cognitive performance (Joshi YB et al, Am J Psych. Epub ahead of print). What do we do with all this information?

Dr. Gray: This is a good distinction—cognitive performance versus dementia (or cognitive decline). Unlike dementia, it is well known that anticholinergics are associated with lower performance on tests of cognition. Keep in mind, with cross-sectional studies you cannot determine that the anticholinergics are the reason for poor cognition. There may be other factors that explain the poorer performance. Nevertheless, whenever possible, we should use the fewest number of anticholinergics as possible when treating people with schizophrenia to minimize effects on cognition.

CHPR: And we should be particularly mindful of strongly anticholinergic medications, right?

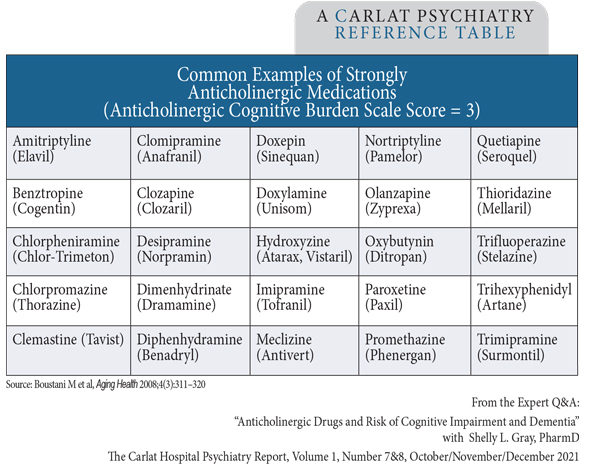

Dr. Gray: Right—medications that score 3 on scales of anticholinergic activity, like the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (Editor’s note: See table at right).

CHPR: So, if we have a patient on clozapine and we want to add an antidepressant, we might want to stay away from paroxetine. Or if a patient is on oxybutynin for urinary incontinence and we want to initiate an antipsychotic, it’s best to choose one that’s not on this list, like aripiprazole or risperidone.

Dr. Gray: Exactly. Look at the patient’s med list. If an anticholinergic is still the best option for the patient, consider reducing or discontinuing other anticholinergics to keep the overall burden to a minimum.

CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Gray.

Hospital PsychiatryDr. Gray: My research uses large databases to examine medication safety issues in older adults with the goal of optimizing healthy aging. My focus is on examining medications and risk for dementia, falls, and fractures—the types of outcomes that are not easily addressed in randomized controlled trials.

CHPR: And in your research on medications and risk for dementia, you have found that anticholinergic medications are associated with an increased risk.

Dr. Gray: Exactly. We conducted a study of older adult subjects who did not have a dementia diagnosis at study entry and found that those with higher cumulative exposure to anticholinergic agents were significantly more likely to receive this diagnosis after, on average, seven years (Gray SL et al, JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(3):401–407).

CHPR: Have other studies had similar findings?

Dr. Gray: Yes. To give a couple of examples, a case-control study of over 40,000 older adult patients reported that certain classes of anticholinergic medications were strongly associated with higher risk of new-onset dementia (Richardson K et al, BMJ 2018;361:k1315). Another study, which looked at nearly 300,000 subjects age 55 and above, found a nearly 50% increased risk of dementia associated with three years of daily use of strong anticholinergic medications (Coupland CAC et al, JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(8):1084–1093).

CHPR: How much should these studies worry us? After all, for years we thought benzodiazepines increased the risk for dementia, but new data show they don’t seem to increase this risk.

Dr. Gray: Right. The results of recent research using high-quality study designs do not support a link between benzodiazepines and dementia (Espinoza RT, J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21(2):143–145). There are a lot of issues that can complicate these pharmacoepidemiology studies—and that’s true for studies that have examined anticholinergics too.

CHPR: Can you say more on the limitations of pharmacoepidemiology studies?

Dr. Gray: Sure. These studies rely on pharmacy prescription fills, and patients don’t always adhere to their prescribed medications. Patients may take over-the-counter meds that aren’t included in studies’ analyses, and they may inaccurately estimate their alcohol and nicotine use. Protopathic bias is another important concern.

CHPR: What is protopathic bias?

Dr. Gray: It occurs when a drug is used to treat early symptoms of a disease that has not yet been diagnosed. Patients take benzodiazepines and anticholinergics in the years leading up to a dementia diagnosis for treatment of prodromal symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia. If researchers don’t take this use into account, their studies will show spurious positive associations.

CHPR: When research takes these limitations and biases into account, do studies still show a strong association between anticholinergic drugs and dementia?

Dr. Gray: Yes. We can’t 100% rule out that biases are not an issue, but several studies have done a good job addressing these issues.

CHPR: Is the research consistent in finding a link between anticholinergics and cognitive impairment?

Dr. Gray: There are some discrepancies in the research. For example, in a study I mentioned earlier, the risk of cognitive impairment was linked with anticholinergic antidepressant, urological, and antiparkinsonian drugs, but not gastrointestinal medications (Richardson et al, 2018). But as a whole, the literature supports an association.

CHPR: We know that acetylcholine is important for memory and learning, so it’s reasonable to worry that medications that reduce cholinergic activity might adversely affect cognition.

Dr. Gray: Right, and the main drugs approved for dementia are cholinesterase inhibitors, which increase levels of acetylcholine.

CHPR: If cognitive impairment is directly linked to anticholinergic medications, is the impairment reversible once these medications are stopped?

Dr. Gray: Unfortunately, this question hasn’t received a lot of attention. A study of older adults who were followed over four years reported that the risk of cognitive decline was about 1.5–2 times higher for continuous anticholinergic users but not for those who discontinued the medications (Carrière I et al, Arch Intern Med 2009;169(14):1317–1324). That’s reassuring—but in my study (Gray et al, 2015), we found the dementia risk was similar among people with past heavy use of anticholinergics and people with recent heavy use, suggesting that the risk for dementia with anticholinergic use persists despite discontinuation.

CHPR: It sounds like most research on anticholinergic agents and cognitive impairment has focused on older adults.

Dr. Gray: Yes, since older patients are at greater risk for cognitive decline and are more prone to side effects. However, we also have limited evidence linking anticholinergic exposure with deteriorating cognition in younger patients. More studies with better methods are needed to determine the risks in younger people.

CHPR: And even in subjects younger than age 50. I read a recent study that looked at the relationship between anticholinergic medication exposure and cognitive performance in patients as young as age 18 with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and found that higher anticholinergic burden was significantly associated with worse cognitive performance (Joshi YB et al, Am J Psych. Epub ahead of print). What do we do with all this information?

Dr. Gray: This is a good distinction—cognitive performance versus dementia (or cognitive decline). Unlike dementia, it is well known that anticholinergics are associated with lower performance on tests of cognition. Keep in mind, with cross-sectional studies you cannot determine that the anticholinergics are the reason for poor cognition. There may be other factors that explain the poorer performance. Nevertheless, whenever possible, we should use the fewest number of anticholinergics as possible when treating people with schizophrenia to minimize effects on cognition.

CHPR: And we should be particularly mindful of strongly anticholinergic medications, right?

Dr. Gray: Right—medications that score 3 on scales of anticholinergic activity, like the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (Editor’s note: See table at right).

CHPR: So, if we have a patient on clozapine and we want to add an antidepressant, we might want to stay away from paroxetine. Or if a patient is on oxybutynin for urinary incontinence and we want to initiate an antipsychotic, it’s best to choose one that’s not on this list, like aripiprazole or risperidone.

Dr. Gray: Exactly. Look at the patient’s med list. If an anticholinergic is still the best option for the patient, consider reducing or discontinuing other anticholinergics to keep the overall burden to a minimum.

CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Gray.

Table: Common Examples of Strongly Anticholinergic Medications

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

KEYWORDS alzheimers anticholinergic-burden-scale anticholinergics benzodiazepines cognitive-decline cognitive-impairment dementia healthy-aging pharmacotherapy

Issue Date: September 13, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)