Home » Tarasoff: Making Sense of the Duty to Warn or Protect

Tarasoff: Making Sense of the Duty to Warn or Protect

January 7, 2022

From The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report

Ahmad Adi, MD, MPH.

Senior Instructor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campu

Hendrick, MD.Editor-in-Chief of the Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report. Chief, Inpatient Psychiatry, Olive View UCLA Medical Center.

Dr. Adi and Dr. Hendrick have disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Your hospitalized patient tells you that he is angry with his sister and intends to “bash her brains in.” He tells you she is sending him messages through the television that say she is going to kill him. Nurses note the patient has been tense and irritable and has been observed talking to himself.

Tarasoff ruling: Background

We often hear about the “Tarasoff warning” and the “duty to protect,” but what do these mean, and who was Tarasoff?

Tatiana Tarasoff was a student at Merritt College in Oakland. In 1968, when she was 18, she met 22-year-old Prosenjit Poddar, a graduate student at UC Berkeley. They dated, but Tarasoff told Poddar that she was seeing other men, and he was crushed, becoming increasingly depressed. He eventually began therapy with Lawrence Moore, a psychologist at the student health service. Poddar told Moore that he intended to kill Tarasoff by stabbing her. In response, Moore informed campus police and recommended that Poddar be civilly committed for treatment of paranoid schizophrenia. Police detained Poddar but released him because he appeared rational. Neither Tarasoff nor her parents received any warning directly. A few months later, Poddar stabbed and killed Tarasoff, carrying out the plan he had confided to his therapist.

The family sued the university, leading eventually to two important California Supreme Court decisions, referred to as Tarasoff I and Tarasoff II. In Tarasoff I, the court ruled that doctors and psychotherapists have a legal obligation to warn a patient’s intended victim if that person is in foreseeable danger from the patient. Warning the police or other authorities is not good enough. This is a concept known as the “duty to warn.”

In Tarasoff II, a rehearing of the case, the court added the concept of “duty to protect.” This duty requires providers to take whatever steps are necessary to protect the intended victim. You can warn them, but you can also protect the intended victim by, for example, placing the patient on an involuntary psychiatric hold. This option has the advantage of not breaching patient confidentiality.

Still, many clinicians continue to warn intended victims in addition to placing patients on involuntary psychiatric holds, from a belief that the Tarasoff ruling requires this warning—but in 2013, California courts clarified that the current duty is solely to protect and disregarded the previous duty to warn (Weinstock R et al, J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2014;42(4):533).

Do you have a duty to warn anyone if a patient makes nonspecific threats to the general public? Most state legislatures have adopted “Tarasoff-limiting statutes” that provide specific criteria for Tarasoff warnings, including the requirement that the threat be made against an identifiable intended victim (Knoll JL, CNS Spectr 2015;20(3):215–222). Of course, in those situations, if you believe the threat to be associated with a mental illness, you would place the patient on an involuntary hold on the grounds of danger to others, thereby keeping the public safe.

Applicability by state

If you don’t work in California, does Tarasoff apply to you? Most states have adopted similar or modified versions of Tarasoff. In 26 states and Puerto Rico, Tarasoff applies much the same way as it does in California (see map of“ Implementations of Tarasoff in the U.S.”: www.thecarlatreport.com/duty) in that the duty is mandatory—ie, you may face civil liability, fines, or other penalties if you fail to warn/protect a potential victim.

You can find each state’s laws here: www.tinyurl.com/mves5y29

Evaluating risk

Even if you live in a state with a clear-cut Tarasoff ruling, you will still face legal ambiguity: How do you decide whether a patient’s threats are serious enough to warrant action? Your patient might express violent fantasies but have no intention of following through with them. In a 12-month study of patients who made explicit and clear violent threats, 23% of the threats resulted in a violent act by the threatening party (Warren LJ et al, Behav Sci Law 2011;29(2):141–154). Here are some ways you can hone your risk appraisals:

- Look for red flags that increase the likelihood of a threat leading to actual violence: prior violence, substance use, and untreated mental illness (Warren et al, 2011).

- Ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the threat clear and imminent?

- Is the patient able to carry out the threat?

- Has the patient engaged in preparatory actions, such as buying a weapon or rehearsing a planned attack?

- Is the intended victim identifiable?

- Consider the difference between a patient with dementia who threatens to “hurt people who want to hurt me” versus a patient with psychosis who informs you that they plan to stab a specific family member later that day as they exit their home because they believe that family member is trying to poison them. The second patient presents a far more urgent scenario, warranting immediate action to warn/protect.

You gently attempt to obtain more information about the seriousness of your patient’s threat. He tells you, “I know my sister is plotting to kill me. Once I’m discharged from the hospital, I’ll wait for her outside of her job so I can finish her off as soon as she leaves the building.”

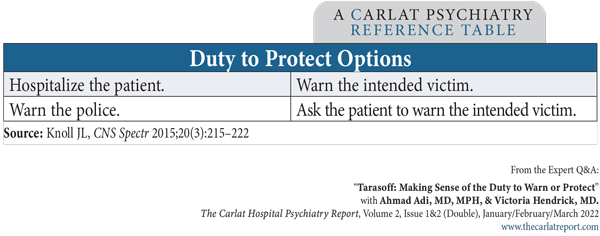

When you have a compelling reason to believe that a third party is in danger, you must take steps to protect that person (see “Duty to Protect Options” table). If you’re unable to place the patient on an involuntary psychiatric hold, you’ll need to warn the intended victim and notify the police.

If you don’t have any contact information for the intended victim, you can try to reach out to the patient’s family members who might have the intended victim’s contact information, or you can conduct an online search. Let the police department know if you are still unable to reach the intended victim. Document all of these efforts in an accurate and timely manner, and be clear as to your reasoning and actions. Describe the threat using verbatim quotes. If you contact the police, take down the name and badge number of the officer you speak with.

Table: Duty to Protect Options

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

You prescribe an antipsychotic for your patient, but he refuses to take it, so you seek a court order to treat the patient involuntarily. Once this is granted, the patient takes his meds twice daily, and you note his behavior has become increasingly calm and appropriate. He is no longer seen talking to himself, and his paranoid delusions resolve. He denies any intention of harming his sister. You discharge him as he no longer appears to pose a threat of imminent violence. He agrees to follow up with outpatient treatment.

CHPR Verdict: Ultimately, our clinical judgment and our good faith efforts to protect potential victims are the most important tools in preventing harm to a third party. Most states have adopted statutes concerning a duty to warn or protect, like California’s Tarasoff rule. While we risk breaching confidentiality, our overriding principle is to make good faith efforts to protect intended victims. By involuntarily hospitalizing and treating a patient so they no longer pose an imminent threat, we can fulfill our obligation to protect third parties without needing to contact the intended victim and thereby breach confidentiality. But check your state’s laws, and keep in mind that the most prudent course of action is to protect and warn.

KEYWORDS crime criminal-behavior duty-to-protect duty-to-warn forensic psychiatry free_articles legal-issues tarasoff

Issue Date: January 7, 2022

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)