Home » Management of Psychogenic Polydipsia

CLINICAL UPDATE

Management of Psychogenic Polydipsia

March 23, 2022

From The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report

Susie Morris, MD.

Assistant professor of psychiatry and forensic psychiatrist, UCLA. Los Angeles, CA.

Dr. Morris has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Your new patient came from jail and has a history of schizophrenia. In jail, he was prescribed chlorpromazine and was observed to drink water compulsively, even from his cell toilet. On interview, he seems confused and disoriented, and he urinates on himself. The nurses tell you he has been complaining of thirst and needs to urinate frequently. You order an electrolyte panel and note that his serum sodium is 126 mEq/L.

Psychogenic polydipsia (PP), also known as primary polydipsia and potomania, was first described in the 1930s. It was mainly observed in patients with psychotic disorders who drank too much water, leading to frequent urination and low sodium levels. The cause is unknown, but these patients may have an acquired defect in hypothalamic thirst regulation. Several psychotropic medications are believed to cause and/or exacerbate PP, possibly triggered by their anticholinergic effects that produce an uncomfortable sensation of dry mouth. These drugs include phenothiazines like chlorpromazine, SSRIs, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, haloperidol, MAOIs, amitriptyline, and valproate (Dundas B et al, Curr Psychiatry Rep 2007;9(3):236–241).

Diagnosing PP

PP is surprisingly common, with a prevalence of 3%–25% in institutionalized patients (Iftene F et al, Psychiatry Res 2013;210(3):679–683). It is most commonly associated with schizophrenia, with an incidence of 11%–20%, but it also occurs in patients with other psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders (Sailer C et al, Swiss Med Wkly 2017;147:w14514). PP has been observed in restrictive eating disorders, most likely from poor nutrition. Inadequate nutrition also places patients with substance use disorders at risk for PP. For instance, “beer potomania,” aptly named for drinking to the exclusion of proper nutrition, results in low sodium and other electrolyte abnormalities typical of PP. Some users of MDMA or ecstasy can also develop PP.

Two other conditions also cause polydipsia and polyuria and should be ruled out before diagnosing PP: diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus. Here are the differences in pathophysiology:

Finally, it’s important to keep one other condition in mind, because it occurs frequently in elderly patients taking psychiatric drugs: syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). In SIADH, the primary problem is too much ADH in the system, caused by various medications including oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, and serotonergic antidepressants. The kidneys are being told to absorb excessive water, so the serum is dilute, but the urine is concentrated (unlike PP). Risk factors include being elderly, female, or underweight. If a patient is on an SSRI, switch to a non-serotonergic antidepressant like bupropion or mirtazapine.

Managing PP

The most important treatment strategy for PP is fluid restriction (1000–1500 mL/day), which sounds simple in theory but is more complex in practice. Theoretically, you can write an order in the chart to limit a patient’s fluid intake to a certain amount, but that’s difficult to enforce on a busy inpatient unit since patients will have access to a bathroom. Some patients may find surreptitious ways of drinking water (eg, from the toilet or sink). If you suspect this is occurring, they may need 1:1 supervision. Have nursing attendants monitor patients by keeping the door ajar when they use the bathroom.

At any rate, if water is successfully restricted, serum sodium will improve rapidly. If the patient’s sodium remains low, you can supplement with sodium chloride tablets, 1–3 g daily.

You should also try to determine if any of the patient’s medications might have triggered or worsened PP—these are typically anticholinergic antipsychotics that cause dry mouth, such as chlorpromazine, haloperidol, or tricyclic antidepressants.

In severe cases of PP—when serum sodium drops to the low 120s or below—patients may present not only with delirium, but also with seizures and obtundation. Serious cases of PP can be fatal, due to cerebral edema and central herniation. Patients with sodium levels < 120 mEq/L and/or serious symptoms require transfer to a medicine unit for closely monitored sodium repletion using intravenous saline (a 3% saline solution).

To prevent recurrent episodes of hyponatremia, patients may need to have sodium levels checked at regular intervals depending on the severity of their PP; you can prescribe daily sodium supplements as needed. Also, behavioral interventions and group therapeutic strategies have shown promising results in preventing relapses (Sailer et al, 2017). Nicotine dependence, a common comorbidity in patients with schizophrenia, can place patients at risk for PP, so smoking cessation can be helpful. Small studies have reported that the opioid antagonist naltrexone, used 50 mg daily as an adjunct to an antipsychotic, reduces compulsive drinking (Rizvi S et al, Cureus 2019;11(8):e5320).

Your patient’s urine does not show evidence of glucosuria, further confirming your diagnosis of PP. You stop the patient’s chlorpromazine and restrict his water intake by withholding water overnight. When you recheck his sodium in the morning, it’s risen to 133 mEq/L.

CHPR Verdict: Low sodium and dilute urine almost always indicate psychogenic polydipsia. Restrict water overnight, stop any potentially offending agents, provide sodium chloride supplements, and recheck serum sodium in the morning. Some patients require 1:1 supervision to restrict water consumption. In severe cases, transfer your patient to the medical unit for IV saline repletion. The opioid antagonist naltrexone may help reduce compulsive water intake.

Hospital Psychiatry Clinical UpdatePsychogenic polydipsia (PP), also known as primary polydipsia and potomania, was first described in the 1930s. It was mainly observed in patients with psychotic disorders who drank too much water, leading to frequent urination and low sodium levels. The cause is unknown, but these patients may have an acquired defect in hypothalamic thirst regulation. Several psychotropic medications are believed to cause and/or exacerbate PP, possibly triggered by their anticholinergic effects that produce an uncomfortable sensation of dry mouth. These drugs include phenothiazines like chlorpromazine, SSRIs, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, haloperidol, MAOIs, amitriptyline, and valproate (Dundas B et al, Curr Psychiatry Rep 2007;9(3):236–241).

Diagnosing PP

PP is surprisingly common, with a prevalence of 3%–25% in institutionalized patients (Iftene F et al, Psychiatry Res 2013;210(3):679–683). It is most commonly associated with schizophrenia, with an incidence of 11%–20%, but it also occurs in patients with other psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders (Sailer C et al, Swiss Med Wkly 2017;147:w14514). PP has been observed in restrictive eating disorders, most likely from poor nutrition. Inadequate nutrition also places patients with substance use disorders at risk for PP. For instance, “beer potomania,” aptly named for drinking to the exclusion of proper nutrition, results in low sodium and other electrolyte abnormalities typical of PP. Some users of MDMA or ecstasy can also develop PP.

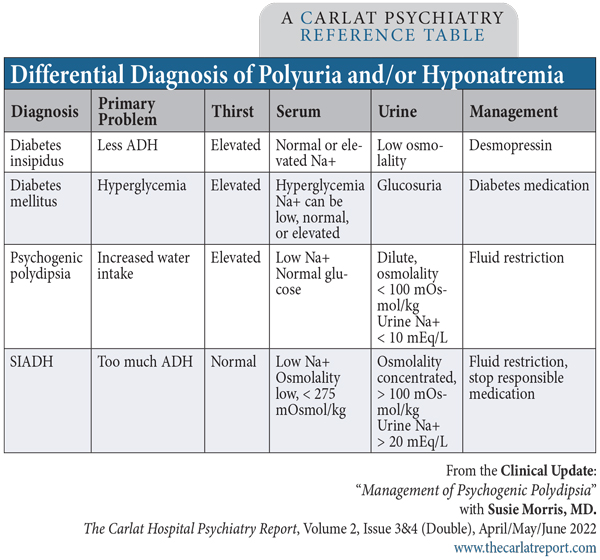

Two other conditions also cause polydipsia and polyuria and should be ruled out before diagnosing PP: diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus. Here are the differences in pathophysiology:

- In PP, the primary problem is that the patient is drinking too much water. This leads to a dilution of the blood, and a chemistry panel will show low sodium (< 135 mEq/L) as well as low serum osmolality. In addition, the urine will be diluted, with a urine osmolality < 100 mOsmol/kg and a low urine sodium (see “Differential Diagnosis of Polyuria and/or Hyponatremia” table below for more information).

- In diabetes mellitus, the primary problem is hyperglycemia, which leads to polyuria because excess glucose is being dumped into the urine, drawing excess water along with it via osmotic diuresis. The excess thirst is a result of the dehydration caused by the polyuria. The key diagnostic features, predictably, are hyperglycemia and glucosuria (glucose in the urine)—neither of which are expected in PP.

- In diabetes insipidus, the primary problem is neither excess water intake nor hypoglycemia, but lowered secretion of, or lowered response to, ADH (antidiuretic hormone). In nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, ADH secretion from the brain is normal, but the kidneys are less sensitive to ADH. It is sometimes caused by long-term lithium use and consequent chronic kidney disease. As in PP, you’ll see a dilute urine, but unlike PP, serum sodium will be high as the serum is concentrated from free water loss.

Finally, it’s important to keep one other condition in mind, because it occurs frequently in elderly patients taking psychiatric drugs: syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). In SIADH, the primary problem is too much ADH in the system, caused by various medications including oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, and serotonergic antidepressants. The kidneys are being told to absorb excessive water, so the serum is dilute, but the urine is concentrated (unlike PP). Risk factors include being elderly, female, or underweight. If a patient is on an SSRI, switch to a non-serotonergic antidepressant like bupropion or mirtazapine.

Table: “Differential Diagnosis of Polyuria and/or Hyponatremia”

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Managing PP

The most important treatment strategy for PP is fluid restriction (1000–1500 mL/day), which sounds simple in theory but is more complex in practice. Theoretically, you can write an order in the chart to limit a patient’s fluid intake to a certain amount, but that’s difficult to enforce on a busy inpatient unit since patients will have access to a bathroom. Some patients may find surreptitious ways of drinking water (eg, from the toilet or sink). If you suspect this is occurring, they may need 1:1 supervision. Have nursing attendants monitor patients by keeping the door ajar when they use the bathroom.

At any rate, if water is successfully restricted, serum sodium will improve rapidly. If the patient’s sodium remains low, you can supplement with sodium chloride tablets, 1–3 g daily.

You should also try to determine if any of the patient’s medications might have triggered or worsened PP—these are typically anticholinergic antipsychotics that cause dry mouth, such as chlorpromazine, haloperidol, or tricyclic antidepressants.

In severe cases of PP—when serum sodium drops to the low 120s or below—patients may present not only with delirium, but also with seizures and obtundation. Serious cases of PP can be fatal, due to cerebral edema and central herniation. Patients with sodium levels < 120 mEq/L and/or serious symptoms require transfer to a medicine unit for closely monitored sodium repletion using intravenous saline (a 3% saline solution).

To prevent recurrent episodes of hyponatremia, patients may need to have sodium levels checked at regular intervals depending on the severity of their PP; you can prescribe daily sodium supplements as needed. Also, behavioral interventions and group therapeutic strategies have shown promising results in preventing relapses (Sailer et al, 2017). Nicotine dependence, a common comorbidity in patients with schizophrenia, can place patients at risk for PP, so smoking cessation can be helpful. Small studies have reported that the opioid antagonist naltrexone, used 50 mg daily as an adjunct to an antipsychotic, reduces compulsive drinking (Rizvi S et al, Cureus 2019;11(8):e5320).

Your patient’s urine does not show evidence of glucosuria, further confirming your diagnosis of PP. You stop the patient’s chlorpromazine and restrict his water intake by withholding water overnight. When you recheck his sodium in the morning, it’s risen to 133 mEq/L.

CHPR Verdict: Low sodium and dilute urine almost always indicate psychogenic polydipsia. Restrict water overnight, stop any potentially offending agents, provide sodium chloride supplements, and recheck serum sodium in the morning. Some patients require 1:1 supervision to restrict water consumption. In severe cases, transfer your patient to the medical unit for IV saline repletion. The opioid antagonist naltrexone may help reduce compulsive water intake.

KEYWORDS diabetes-insipidus fluid-restriction hyponatremia low-sodium naltrexone osmolality siadh sodium-supplementation water-intoxication water-restriction

Issue Date: March 23, 2022

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)