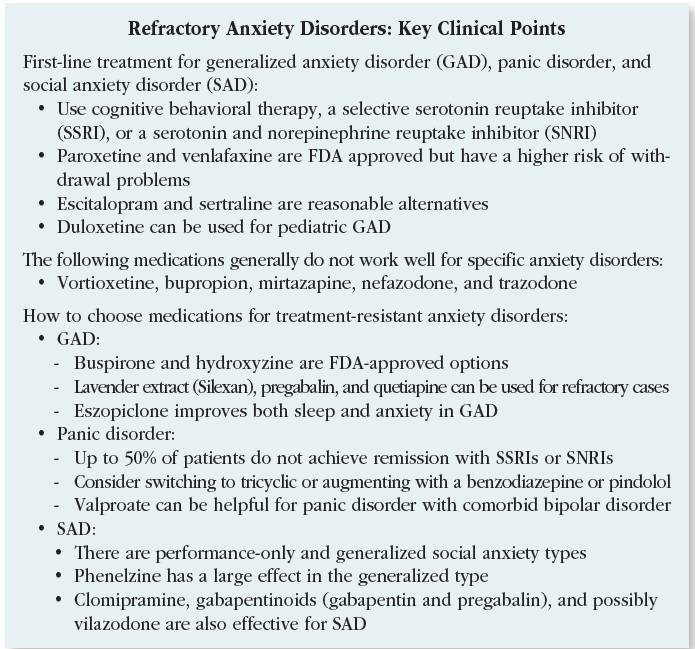

Special Report: Refractory Anxiety Disorders Part 2: When First Lines Fail

Part 2: When First Lines Fail

See part 1 of this special report here.

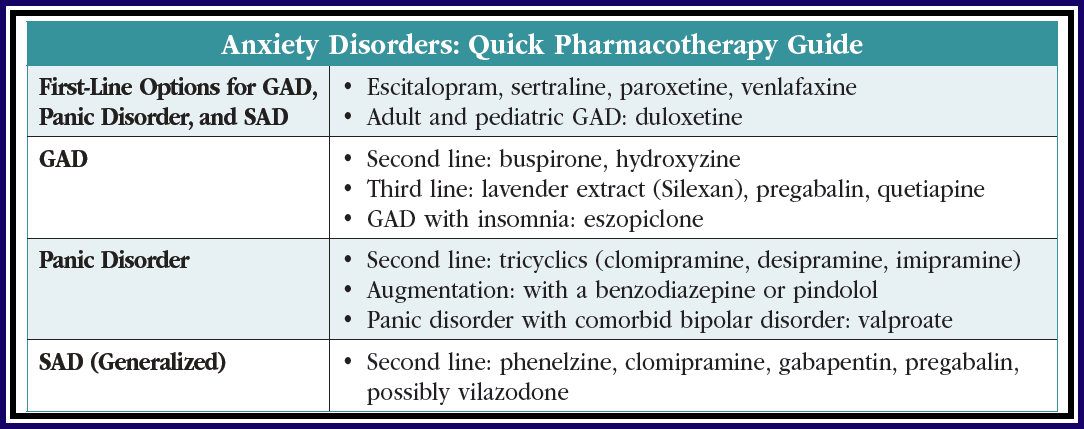

Generalized anxiety disorder

When SSRIs and SNRIs do not work in GAD, we have two FDA-approved options worth trying: buspirone and the often-overlooked hydroxyzine. Buspirone (15–20 mg BID or TID) is well tolerated, with low rates of sedation and no sexual side effects, but its efficacy is low with an effect size of around 0.2. Hydroxyzine is an antihistamine with decent effect sizes that are close to benzodiazepines for GAD (0.4–0.5). Its main drawbacks are sedation and—especially in the elderly—anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, constipation, and confusion. On the other hand, hydroxyzine may still be preferable to benzodiazepines, which are associated with confusion, falls, and addiction.

For refractory cases, lavender extract (Silexan), pregabalin, and quetiapine are reasonable options. All of these were studied as monotherapy but can be safely added to antidepressants as well.

Silexan is a proprietary lavender extract with demonstrated efficacy in GAD. Taken orally, it is approved in Europe for this disorder. In the US it is sold over the counter as CalmAid. Although not studied in treatment-resistant anxiety, Silexan boasts a larger effect size than SSRIs, SNRIs, and benzodiazepines, coming in at 0.5–0.9 across placebo-controlled trials (80–160 mg/day). In GAD, it surpassed paroxetine in a large head-to-head trial and equaled low-dose lorazepam in a network analysis (Yap S et al, Sci Rep 2019;9(1):18042). Silexan is well tolerated with typical side effects of mild GI symptoms such as lavender-flavored burping, which improve by taking it at night. It does not cause sedation yet helps with anxiety-related sleep problems. Dependence, withdrawal, and drug interactions have all been examined and do not appear to be issues (see TCPR, July 2020).

Pregabalin (Lyrica) is approved for GAD in many countries and is available as a generic in the US. In anxiety disorders, it can be used as a sole treatment or an adjunct in doses from 150–600 mg/day total, given in two divided doses. It has a moderate effect size of 0.37 and a reasonable safety profile (Generoso MB et al, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2017;32:49–55). Benefits are seen as early as the first week, which is faster than the SSRIs and SNRIs by a few weeks. Side effects tend to be mild and include dose-dependent sedation, dry mouth, and weight gain.

Pregabalin might be your agent of choice for patients who have comorbid fibromyalgia or diabetic neuropathy, which are FDA-approved indications. Pregabalin has two “gabapentinoid” cousins, but one failed in three large, industry-sponsored trials of GAD (tiagabine) and the other—although popular—is supported only by a single case report (gabapentin).

Quetiapine is approved for GAD in Europe but did not earn approval in the US despite multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing substantial efficacy. The FDA believed this antipsychotic carried too many risks to justify approval in a seemingly mild condition like GAD, but for patients with disabling anxiety, the benefits may outweigh those risks.

Quetiapine is approved for GAD in Europe but did not earn approval in the US despite multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing substantial efficacy. The FDA believed this antipsychotic carried too many risks to justify approval in a seemingly mild condition like GAD, but for patients with disabling anxiety, the benefits may outweigh those risks.

Quetiapine’s effect size in GAD is in the large range, compared to a small effect with SSRIs. Quetiapine might be particularly useful for GAD among patients who also have mood disorders where it is FDA approved, such as bipolar and unipolar depression.

Another off-label avenueis sleep. Adding eszopiclone (Lunesta) to escitalopram significantly improved anxiety, sleep, and daytime functioning among patients with GAD, suggesting it also works as an augmentation agent overall (Pollack MH et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65(5):551–562). Eszopiclone is metabolized into a benzo-like compound that is active during the day, which may be why other hypnotics like zolpidem did not treat anxiety in studies with similar design.

CARLAT TAKE

Consider Silexan, pregabalin, and quetiapine when first-line treatments don’t bring recovery in GAD.

Panic disorder

As many as 50% of patients with panic disorder do not achieve full or stable remission with first-line treatments like the SSRIs and SNRIs. Among these antidepressants, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine are FDA approved in panic disorder, but there is evidence that citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, and duloxetine are effective as well.

For patients who don’t respond well to first-line treatments, options include switching to a tricyclic or augmenting with a benzodiazepine or pindolol.

Among the tricyclic antidepressants, imipramine, clomipramine, and desipramine all have RCTs showing efficacy, but they are not much more effective than agents that are more easily tolerated, such as the SSRIs and SNRIs. The nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) phenelzine and tranylcypromine have significant efficacy for panic disorder, but only when it is comorbid with SAD. Dietary restrictions and side effects such as orthostasis, sedation, sexual dysfunction, constipation, and dry mouth limit their use as tolerability is relatively low.

Benzodiazepines have more empiric support in panic disorder than any other anxiety disorder, but their side effect profile—including risk of addiction—puts them lower in treatment algorithms. Alprazolam and clonazepam are the two benzodiazepines that have FDA approval for panic disorder. These agents may be necessary when patients don’t respond to other options or as a temporary addition for symptom relief while waiting for SSRIs or SNRIs to take full effect, although this use has not been studied. In a recent meta-analysis, benzodiazepines were 27% more likely to lead to remission than SSRIs but had higher rates of adverse effects (Chawla N et al, BMJ 2022;376:e066084).

Daily use of benzodiazepines may be appropriate if the medication improves functioning. The approved dose ranges for panic disorder are quite large (up to 10 mg/day for alprazolam and 4 mg/day for clonazepam), but sticking to lower doses reduces tolerability problems. Average doses in panic disorder trials were clonazepam 1–2 mg/day and alprazolam 2–5 mg/day.

The beta blocker pindolol may be the only medication with evidence in well-defined, treatment-resistant panic disorder, but this has only been shown in a small RCT (Hirschmann S et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20(5):556–559). In that study, pindolol was added to fluoxetine among patients who had failed two antidepressant trials and an eight-week trial of fluoxetine alone. Pindolol 2.5 mg TID added to fluoxetine 20 mg/day was significantly better than the addition of placebo in improving panic disorder symptoms.

Valproate may have some utility in panic disorder, though the evidence comes only from small open-label trials using doses of 500–2250 mg/day total. Like benzos, valproate has GABAergic properties and may be an option for patients with comorbid panic and bipolar disorders (Keck PE et al, Biol Psychiatry 1993;33(7):542:546). Other anticonvulsants (tiagabine, gabapentin) have been explored without success in panic disorder, and topiramate has induced panic attacks in case reports. Antipsychotics do not have a role here either. Despite its success in GAD, quetiapine failed in a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of panic disorder.

CARLAT TAKE

Consider pindolol augmentation for treatment-resistant cases of panic disorder and short-term benzodiazepines for immediate relief.

Social anxiety disorder

There are two types of SAD: performance-only social anxiety and generalized social anxiety. Performance-only social anxiety seems to respond to pre-performance beta blockers like propranolol, although there is a surprising lack of RCT evidence for this popular strategy. Beta blockers do not work in generalized social anxiety, which is characterized by anxiety related to a variety of situations and more pervasive impairment.

SSRIs and SNRIs work for some patients with SAD, but they leave many patients shy of full remission. In those situations, phenelzine offers hope. This medication had a large effect size across five RCTs of SAD totaling 454 patients, compared to the small effect seen with SSRIs.* In some of these trials, phenelzine compared favorably to group CBT and successfully augmented psychotherapy. The starting dose for phenelzine is 15 mg, and doses up to 90 mg may be needed. Preliminary evidence supports tranylcypromine, another nonselective MAOI, in SAD.

Outside of SSRIs and MAOIs, most antidepressants have failed in this population (eg, imipramine, mirtazapine, buspirone). Exceptions are clomipramine (25–150 mg/day) and vilazodone (40 mg/day), which have small positive controlled trials in SAD (Simpson HB et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18(2):132–135; Careri JM et al, Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2015;17(6):10.4088/PCC.15m01831).

The gabapentinoids also have a role in SAD, and in this case the evidence supports both gabapentin and pregabalin. The doses need to get quite high to show effect, such as 2000 mg/day for gabapentin (Pande AC et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999;19:341–348) and 600 mg/day total for pregabalin (Feltner DE et al, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;26;213–220), given in divided doses three times per day. Quetiapine has a positive placebo-controlled trial, but the sample size (15) was too small to endorse it in SAD.

Benzodiazepines have successfully augmented SSRIs, and they can be useful on an as-needed basis prior to anxiety-provoking situations (Seedat S and Stein MB, J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(2):244–248). Many patients with SAD tend to use alcohol to self-medicate, so be cautious when considering a benzodiazepine prescription to ensure the patient does not combine these two GABAergic sedatives. They are best avoided when patients are undertaking exposure therapies like CBT, as benzodiazepines can block fear-extinction learning. We would avoid adding a benzo in those situations, but tapering off an existing benzo may be too challenging.

We don’t have a lot of good evidence on what to do after an initial trial with an SSRI or SNRI for a patient with persistent symptoms—should we augment or switch? One study examined this in SAD among patients who did not respond sufficiently to sertraline. Patients were randomized to placebo, augmentation with flexible-dose clonazepam (up to 3 mg), or a switch to venlafaxine. Adding clonazepam led to significant reduction in SAD symptoms, but there was no significant difference in the number of patients achieving remission across the three groups (Pollack MH et al, Am J Psychiatry 2014;17(1):14–53).

CARLAT TAKE

In SAD, phenelzine may work when first-line options have failed.

See part 1 of this special report here.

*Erratum: In the print version of TCPR, the paper originally said "This medication had a large effect size across five RCTs of SAD totaling 454 patients, compared to the small effect seen with MAOIs." It should have said, "This medication had a large effect size across five RCTs of SAD totaling 454 patients, compared to the small effect seen with SSRIs."

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)