Home » Weight Gain and Metabolic Side Effects

Weight Gain and Metabolic Side Effects

July 14, 2021

From The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report

Stephen Marder, MD

Stephen Marder, MD

Daniel X. Freedman Professor of Psychiatry. Vice Chair for Education, Semel Institute for Neuroscience at UCLA. Director, VA VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, San Diego, CA.

Dr. Marder has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to educational activity.

CHPR: Dr. Marder, can you please tell us about your work?

Dr. Marder: Sure. My work has focused on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to improving the outcomes of serious mental illnesses, particularly schizophrenia. I’m very interested in ways to combine psychosocial interventions with pharmacological approaches and to reduce adverse side effects of antipsychotic medications, such as weight gain and diabetes.

CHPR: How big of a problem is antipsychotic-induced weight gain (AIWG) and metabolic syndrome?

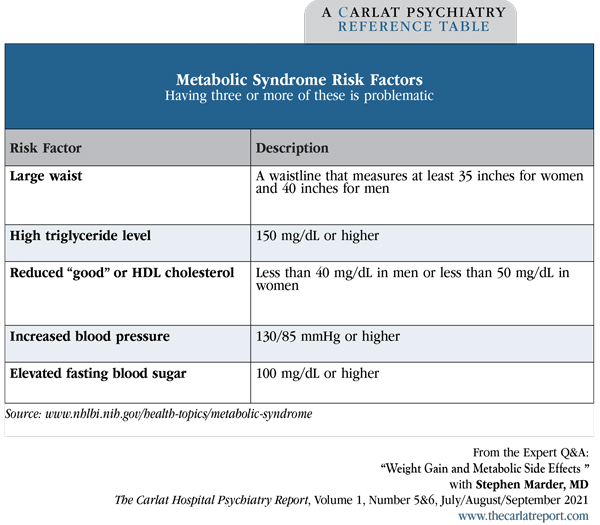

Dr. Marder: It’s a big problem. Individuals with schizophrenia are at high risk of obesity, elevated lipids, increased insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. On average, people with schizophrenia die 20–25 years sooner than people without schizophrenia. It’s important for clinicians to be mindful of the metabolic effects—those that are related to the illness itself and those that result from treatments, particularly antipsychotic drugs

CHPR: Might other factors contribute to the shortened lifespan?

Dr. Marder: Certainly. Many people with schizophrenia tend to be sedentary, are smokers, and have poor diets. Some risk factors, like lack of exercise and poor diet, are modifiable; some are not, like genetic risk. But diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease are major factors contributing to these patients’ shorter lifespans.

CHPR: You mentioned genetic risk. Is there a genetic predisposition for obesity or diabetes among individuals with schizophrenia?

Dr. Marder: Yes. Even drug-naïve people with schizophrenia have three times the risk of developing diabetes, and that’s probably due to shared susceptibility genes between diabetes and schizophrenia. When you add antipsychotic drugs, the risk for diabetes increases by an additional 20% (Rajkumar AP et al, Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(7):686–694).

CHPR: But if a patient on antipsychotic drugs does not gain weight, do we still need to worry about diabetes?

Dr. Marder: That’s a good question. Visceral fat and increased waist circumference are associated with insulin resistance, so in most cases diabetes develops primarily in people who gain weight, but patients can develop insulin resistance even in the absence of weight gain.

CHPR: And there are certain subgroups who are at more risk of weight gain and metabolic syndrome, right?

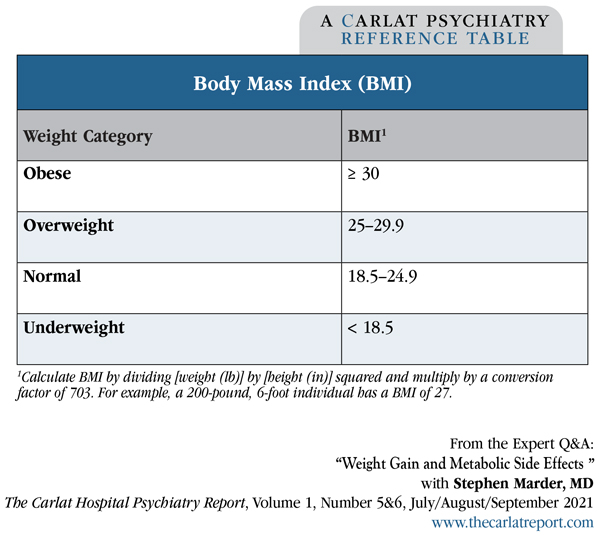

Dr. Marder: Having a lower body mass index (BMI) prior to treatment places people at more risk for weight gain (Editor’s note: See “Body Mass Index” table below). Also, first-episode patients and younger patients are at greater risk, particularly adolescents. And rapid weight gain in the first month of treatment predicts significant long-term weight gain. Other factors associated with medication-induced weight gain are gender (women being at greater risk) and non-Caucasian ethnicities (Vandenberghe F et al, Pharmacogenet Genomics 2016;26(12):547–557).

CHPR: What interventions do you recommend to minimize the risk?

Dr. Marder: A reasonable first intervention is to change antipsychotics to one that is less likely to cause weight gain. Some patients only respond to certain medications, however, so this might not be an option. Adding metformin also helps.

CHPR: So which medications are the most and least likely to cause metabolic changes and weight gain?

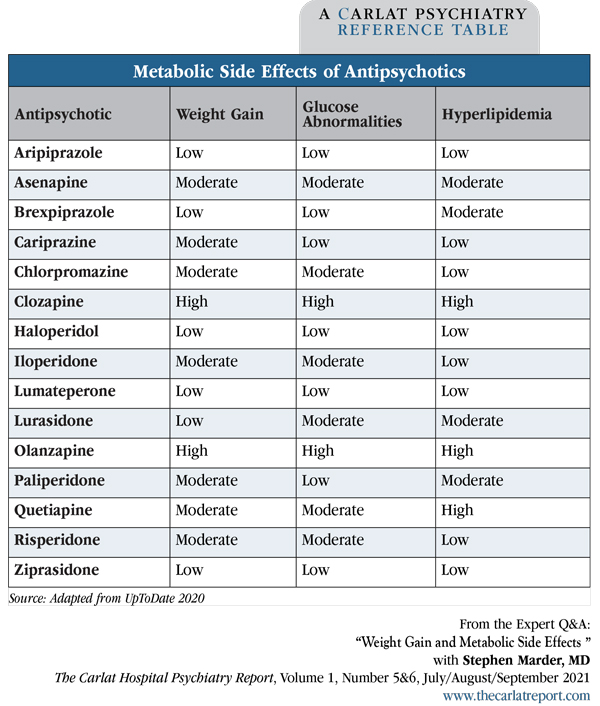

Dr. Marder: Clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine stand out as the medications with the most concerning metabolic profile, and aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone have the lowest risk (Editor’s note: See “Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics” table on page 3). But there are patients who gain weight on drugs that are not considered high risk. For example, when we began doing phase II trials with risperidone in the 1990s, I remember a patient who developed diabetic ketoacidosis on risperidone. Almost all antipsychotics have at least some metabolic risk, so even though aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone are associated with minimal weight gain, some patients will gain weight on these medications.

CHPR: It sounds like we should monitor all patients on antipsychotic agents, not just patients on the worst-offending agents.

Dr. Marder: Yes. We recommend that early in treatment, clinicians check for signs of prediabetes or insulin resistance. That would include ordering either a fasting blood glucose or a hemoglobin A1C within 6–8 weeks of starting a new antipsychotic drug.

CHPR: Do you do any other testing?

Dr. Marder: We also recommend obtaining a lipid panel within 6–8 weeks. An elevation in triglycerides is early evidence indicating that the person will be at greater risk for diabetes and weight gain.

CHPR: And with what sort of frequency should clinicians do the monitoring?

Dr. Marder: At every visit to the clinician, patients should get their weight checked. We also want to make sure patients have a bathroom scale at home so they can weigh themselves regularly and take ownership of this issue.

CHPR: You mentioned metformin earlier. Can you say more about this?

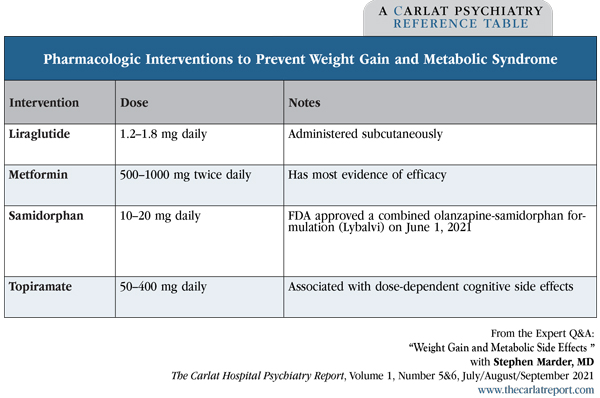

Dr. Marder: We encourage the use of metformin as it’s the pharmacologic intervention with the most evidence, particularly for managing body weight, HbA1c, and fasting blood sugars (Jiang WL et al, Transl Psychiatry 2020;10(1):117). It is easy to prescribe and is usually well tolerated.

CHPR: Which patients should not get metformin?

Dr. Marder: It should not be prescribed to patients with severe kidney or liver disease, congestive heart failure, or metabolic acidosis. Younger patients tend to have the best responses to metformin, so we should be especially mindful of starting metformin for them.

CHPR: Are there any other agents that work?

Dr. Marder: There is some evidence that topiramate is effective, but because of its cognitive side effects, such as impaired attention and memory, it is not our first drug of choice. Liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda) also appears to be effective. In a large randomized controlled trial, patients on liraglutide gained 5.3 kg less than patients on placebo after 16 weeks of treatment daily (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728). The investigators reevaluated the subjects one year later and found that they continued to weigh significantly less than the placebo group.

CHPR: That sounds like a promising treatment! What about the new combination drug, olanzapine-samidorphan, that is awaiting FDA approval?

Dr. Marder: This is a combination pill where samidorphan, an opioid antagonist, is added to olanzapine. Recent data published in The American Journal of Psychiatry shows that it substantially attenuates, though does not entirely prevent, the weight gain from olanzapine (Correll CU et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(12):1168–1178).

CHPR: Can you talk about how the timing of an intervention affects its likelihood of working?

Dr. Marder: It’s important to identify early that somebody is at risk for weight gain. In the guidelines that I participated in, we recommend that clinicians look at signs of weight gain starting in the first weeks of treatment (Keepers GA et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(9):868–872). If somebody gains as little as 1 BMI unit, that’s a concern because it indicates a risk for further weight gain. And intervening early, before a person has put on weight, is more effective than helping patients lose weight after they’ve gained it.

CHPR: I looked at this issue myself in a paper where we reported that the first 3 months of treatment represent a critical period for preventive interventions. Beyond that time, when patients have already gained weight, it’s much harder for them to return to their baseline weight (Hendrick V et al, Ann Clin Psychiatry 2017;29(2):120–124).

Dr. Marder: Yes, many studies have found that AIWG occurs early. So it’s a good idea to initiate preventive interventions in medication-naïve patients if they’re placed on medications that are highly likely to cause weight gain.

CHPR: Do you routinely recommend exercise programs or nutritional counseling?

Dr. Marder: The first thing I do when I start someone on a drug like olanzapine or quetiapine is to make them aware that those drugs cause weight gain. The biology of feeding behavior is complex. Peptides from the intestines communicate with the hypothalamus to regulate eating behavior. Antipsychotics interfere with this process and prevent patients from experiencing satiety. It’s important to inform patients about this effect so they can be mindful of how much they are eating. Mere portion control can prevent weight gain if patients are motivated. I want to emphasize that lifestyle interventions work. Dozens of well-controlled studies have found that various interventions are helpful, including nutritional counseling and encouraging people to keep track of what they are eating and how much exercise they’re getting.

CHPR: Have you found that your patients are generally receptive to these interventions?

Dr. Marder: The interventions are not always easy to implement, but it’s important to dispense with the bias that people with psychotic illnesses are not motivated to regulate their weight. Many of them are, particularly early in the illness. Young people who gain weight are often devastated by it. All these interventions can make a difference. The ones that work best typically include a lot of patient interaction over extended periods of time. You can’t simply do an intervention for 8 or 12 weeks; it’s got to be a sustained intervention. And interventions that include active monitoring are particularly beneficial.

CHPR: What type of active monitoring?

Dr. Marder: There are several types of monitoring devices, like smartphone apps, Fitbits, and other wearable devices, that give patients feedback about whether they are exercising adequately and can motivate them to remain physically active.

CHPR: And we can also help motivate patients by regularly reminding them to exercise.

Dr. Marder: Yes, and the effects of exercise go beyond just weight control and cardiovascular health. Exercise is good for managing the illness itself. It promotes neuroplasticity and improves patients’ memory and ability to learn. Studies done at UCLA and elsewhere show that exercise releases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and increases gray matter (Neuchterlein KH et al, Schizophr Bull 2016;42 Suppl 1:S44–S52). So the effects of exercise are helpful not only for physical health, but also for managing the symptoms of schizophrenia.

CHPR: That’s interesting. Are any factors associated with exercise’s effectiveness?

Dr. Marder: There’s a direct correlation between the amount of exercise and improvements in cognitive functioning (Firth J et al, Schizophr Bull 2017;43(3):546–556). Various domains of cognition improve, including attention and memory, but the greatest improvements are in patients’ social cognitive functioning.

CHPR: I recently came across a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that reported aerobic exercise reduces negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia (Sabe M et al, Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020;62:13–20).

Dr. Marder: Yes, that’s yet another benefit of exercise.

CHPR: So to summarize, early in treatment we should be vigilant for weight and blood sugar changes in our patients on antipsychotic medications; it’s a good idea to intervene early, for example by adding metformin, to prevent weight gain from developing in the first place (Editor’s note: See “Pharmacologic Interventions to Prevent Weight Gain and Metabolic Syndrome” table below); and it’s important to track weight at every visit and encourage portion control and regular exercise.

Dr. Marder: And again, the simplest and sometimes most effective intervention is changing the antipsychotic. It’s a good idea for clinicians to have a list they can easily refer to, listing the relative liabilities of different drugs (Editor’s note: “See Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics” table above).

CHPR: Thank you, Dr. Marder.

Hospital PsychiatryDr. Marder: Sure. My work has focused on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to improving the outcomes of serious mental illnesses, particularly schizophrenia. I’m very interested in ways to combine psychosocial interventions with pharmacological approaches and to reduce adverse side effects of antipsychotic medications, such as weight gain and diabetes.

CHPR: How big of a problem is antipsychotic-induced weight gain (AIWG) and metabolic syndrome?

Dr. Marder: It’s a big problem. Individuals with schizophrenia are at high risk of obesity, elevated lipids, increased insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. On average, people with schizophrenia die 20–25 years sooner than people without schizophrenia. It’s important for clinicians to be mindful of the metabolic effects—those that are related to the illness itself and those that result from treatments, particularly antipsychotic drugs

Table: Metabolic Syndrome Risk Factors

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

CHPR: Might other factors contribute to the shortened lifespan?

Dr. Marder: Certainly. Many people with schizophrenia tend to be sedentary, are smokers, and have poor diets. Some risk factors, like lack of exercise and poor diet, are modifiable; some are not, like genetic risk. But diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease are major factors contributing to these patients’ shorter lifespans.

CHPR: You mentioned genetic risk. Is there a genetic predisposition for obesity or diabetes among individuals with schizophrenia?

Dr. Marder: Yes. Even drug-naïve people with schizophrenia have three times the risk of developing diabetes, and that’s probably due to shared susceptibility genes between diabetes and schizophrenia. When you add antipsychotic drugs, the risk for diabetes increases by an additional 20% (Rajkumar AP et al, Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(7):686–694).

CHPR: But if a patient on antipsychotic drugs does not gain weight, do we still need to worry about diabetes?

Dr. Marder: That’s a good question. Visceral fat and increased waist circumference are associated with insulin resistance, so in most cases diabetes develops primarily in people who gain weight, but patients can develop insulin resistance even in the absence of weight gain.

CHPR: And there are certain subgroups who are at more risk of weight gain and metabolic syndrome, right?

Dr. Marder: Having a lower body mass index (BMI) prior to treatment places people at more risk for weight gain (Editor’s note: See “Body Mass Index” table below). Also, first-episode patients and younger patients are at greater risk, particularly adolescents. And rapid weight gain in the first month of treatment predicts significant long-term weight gain. Other factors associated with medication-induced weight gain are gender (women being at greater risk) and non-Caucasian ethnicities (Vandenberghe F et al, Pharmacogenet Genomics 2016;26(12):547–557).

Table: Body Mass Index

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

CHPR: What interventions do you recommend to minimize the risk?

Dr. Marder: A reasonable first intervention is to change antipsychotics to one that is less likely to cause weight gain. Some patients only respond to certain medications, however, so this might not be an option. Adding metformin also helps.

CHPR: So which medications are the most and least likely to cause metabolic changes and weight gain?

Dr. Marder: Clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine stand out as the medications with the most concerning metabolic profile, and aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone have the lowest risk (Editor’s note: See “Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics” table on page 3). But there are patients who gain weight on drugs that are not considered high risk. For example, when we began doing phase II trials with risperidone in the 1990s, I remember a patient who developed diabetic ketoacidosis on risperidone. Almost all antipsychotics have at least some metabolic risk, so even though aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone are associated with minimal weight gain, some patients will gain weight on these medications.

Table: Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

CHPR: It sounds like we should monitor all patients on antipsychotic agents, not just patients on the worst-offending agents.

Dr. Marder: Yes. We recommend that early in treatment, clinicians check for signs of prediabetes or insulin resistance. That would include ordering either a fasting blood glucose or a hemoglobin A1C within 6–8 weeks of starting a new antipsychotic drug.

CHPR: Do you do any other testing?

Dr. Marder: We also recommend obtaining a lipid panel within 6–8 weeks. An elevation in triglycerides is early evidence indicating that the person will be at greater risk for diabetes and weight gain.

CHPR: And with what sort of frequency should clinicians do the monitoring?

Dr. Marder: At every visit to the clinician, patients should get their weight checked. We also want to make sure patients have a bathroom scale at home so they can weigh themselves regularly and take ownership of this issue.

CHPR: You mentioned metformin earlier. Can you say more about this?

Dr. Marder: We encourage the use of metformin as it’s the pharmacologic intervention with the most evidence, particularly for managing body weight, HbA1c, and fasting blood sugars (Jiang WL et al, Transl Psychiatry 2020;10(1):117). It is easy to prescribe and is usually well tolerated.

CHPR: Which patients should not get metformin?

Dr. Marder: It should not be prescribed to patients with severe kidney or liver disease, congestive heart failure, or metabolic acidosis. Younger patients tend to have the best responses to metformin, so we should be especially mindful of starting metformin for them.

CHPR: Are there any other agents that work?

Dr. Marder: There is some evidence that topiramate is effective, but because of its cognitive side effects, such as impaired attention and memory, it is not our first drug of choice. Liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda) also appears to be effective. In a large randomized controlled trial, patients on liraglutide gained 5.3 kg less than patients on placebo after 16 weeks of treatment daily (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728). The investigators reevaluated the subjects one year later and found that they continued to weigh significantly less than the placebo group.

CHPR: That sounds like a promising treatment! What about the new combination drug, olanzapine-samidorphan, that is awaiting FDA approval?

Dr. Marder: This is a combination pill where samidorphan, an opioid antagonist, is added to olanzapine. Recent data published in The American Journal of Psychiatry shows that it substantially attenuates, though does not entirely prevent, the weight gain from olanzapine (Correll CU et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(12):1168–1178).

CHPR: Can you talk about how the timing of an intervention affects its likelihood of working?

Dr. Marder: It’s important to identify early that somebody is at risk for weight gain. In the guidelines that I participated in, we recommend that clinicians look at signs of weight gain starting in the first weeks of treatment (Keepers GA et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(9):868–872). If somebody gains as little as 1 BMI unit, that’s a concern because it indicates a risk for further weight gain. And intervening early, before a person has put on weight, is more effective than helping patients lose weight after they’ve gained it.

CHPR: I looked at this issue myself in a paper where we reported that the first 3 months of treatment represent a critical period for preventive interventions. Beyond that time, when patients have already gained weight, it’s much harder for them to return to their baseline weight (Hendrick V et al, Ann Clin Psychiatry 2017;29(2):120–124).

Dr. Marder: Yes, many studies have found that AIWG occurs early. So it’s a good idea to initiate preventive interventions in medication-naïve patients if they’re placed on medications that are highly likely to cause weight gain.

CHPR: Do you routinely recommend exercise programs or nutritional counseling?

Dr. Marder: The first thing I do when I start someone on a drug like olanzapine or quetiapine is to make them aware that those drugs cause weight gain. The biology of feeding behavior is complex. Peptides from the intestines communicate with the hypothalamus to regulate eating behavior. Antipsychotics interfere with this process and prevent patients from experiencing satiety. It’s important to inform patients about this effect so they can be mindful of how much they are eating. Mere portion control can prevent weight gain if patients are motivated. I want to emphasize that lifestyle interventions work. Dozens of well-controlled studies have found that various interventions are helpful, including nutritional counseling and encouraging people to keep track of what they are eating and how much exercise they’re getting.

CHPR: Have you found that your patients are generally receptive to these interventions?

Dr. Marder: The interventions are not always easy to implement, but it’s important to dispense with the bias that people with psychotic illnesses are not motivated to regulate their weight. Many of them are, particularly early in the illness. Young people who gain weight are often devastated by it. All these interventions can make a difference. The ones that work best typically include a lot of patient interaction over extended periods of time. You can’t simply do an intervention for 8 or 12 weeks; it’s got to be a sustained intervention. And interventions that include active monitoring are particularly beneficial.

CHPR: What type of active monitoring?

Dr. Marder: There are several types of monitoring devices, like smartphone apps, Fitbits, and other wearable devices, that give patients feedback about whether they are exercising adequately and can motivate them to remain physically active.

CHPR: And we can also help motivate patients by regularly reminding them to exercise.

Dr. Marder: Yes, and the effects of exercise go beyond just weight control and cardiovascular health. Exercise is good for managing the illness itself. It promotes neuroplasticity and improves patients’ memory and ability to learn. Studies done at UCLA and elsewhere show that exercise releases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and increases gray matter (Neuchterlein KH et al, Schizophr Bull 2016;42 Suppl 1:S44–S52). So the effects of exercise are helpful not only for physical health, but also for managing the symptoms of schizophrenia.

CHPR: That’s interesting. Are any factors associated with exercise’s effectiveness?

Dr. Marder: There’s a direct correlation between the amount of exercise and improvements in cognitive functioning (Firth J et al, Schizophr Bull 2017;43(3):546–556). Various domains of cognition improve, including attention and memory, but the greatest improvements are in patients’ social cognitive functioning.

CHPR: I recently came across a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that reported aerobic exercise reduces negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia (Sabe M et al, Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020;62:13–20).

Dr. Marder: Yes, that’s yet another benefit of exercise.

CHPR: So to summarize, early in treatment we should be vigilant for weight and blood sugar changes in our patients on antipsychotic medications; it’s a good idea to intervene early, for example by adding metformin, to prevent weight gain from developing in the first place (Editor’s note: See “Pharmacologic Interventions to Prevent Weight Gain and Metabolic Syndrome” table below); and it’s important to track weight at every visit and encourage portion control and regular exercise.

Dr. Marder: And again, the simplest and sometimes most effective intervention is changing the antipsychotic. It’s a good idea for clinicians to have a list they can easily refer to, listing the relative liabilities of different drugs (Editor’s note: “See Metabolic Side Effects of Antipsychotics” table above).

CHPR: Thank you, Dr. Marder.

Table: Pharmacologic Interventions to Prevent Weight Gain and Metabolic Syndrome

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

KEYWORDS aripiprazole clozapine diabetes exercise insulin-resistance liraglutide metabolic-syndrome metformin olanzapine quetiapine risperidione samidorphan side-effects topiramate waist-circumference weight-gain ziprasidone

Issue Date: July 14, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)