Home » Psychopharmacology for Patients With Intellectual Disability

Psychopharmacology for Patients With Intellectual Disability

September 1, 2017

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Julie Gentile, MD

Professor of psychiatry at the Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University. Project director for Ohio’s Coordinating Center of Excellence in Mental Illness & Intellectual Disability.

Dr. Gentile has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

David Dixon, DO

Clinical chief resident, Wright State University, Department of Psychiatry.

Dr. Dixon has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Julie Gentile, MD

Professor of psychiatry at the Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University. Project director for Ohio’s Coordinating Center of Excellence in Mental Illness & Intellectual Disability.

Dr. Gentile has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

David Dixon, DO

Clinical chief resident, Wright State University, Department of Psychiatry.

Dr. Dixon has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Anne, a 23-year-old woman with moderate intellectual disability, comes into your office accompanied by a staff member of her group home. The staffer reports that Anne has been aggressive toward her roommate and has appeared more aloof over the last week. He is curious whether you can prescribe a medication to prevent future episodes of aggression.

Prescribing psychotropic medications in patients with intellectual disability (ID) requires certain nuances in approach that may be unfamiliar to some psychiatrists. In this article, we’ll discuss some aspects of assessment and treatment that you may find useful when you encounter and work with such patients.

Assessment

1. Ask about psychosocial issues.

We usually begin by ruling out psychosocial causes of the behavior, because these issues can often be fixed without resorting to psychopharmaceuticals and their attendant side effects. Here are some of the more common issues in my experience.

In response to your questions, the staff member reports that there were no changes in Anne’s family contact or routine. In addition, the group home changed the meal menu to items Anne prefers, increased her favorite activities, and reached out to family members, but nothing seems to have worked.

2. Ask about medical issues.

Because ID patients have difficulty communicating, they may have unrecognized medical symptoms affecting their mood and behavior.

When you ask about any medical issues Anne may have had, the staff member says that a recent visit to Anne’s PCP revealed no signs of infection or other medical problem that might have caused her agitation.

3. Assuming that there is a psychiatric cause of agitation, try to narrow down the underlying disorder.

During the interview with Anne, you ask her what happened with her roommate, and her reply is that “he told me to.” The staff reports that Anne’s roommate is female and that no males work in her group home. You notice that Anne seems to be periodically distracted throughout the interview, and you ask her if she knows who “he” is, to which she responds “no.” Further evaluation reveals that Anne has started to hear whispers intermittently. Her eventual diagnosis is schizophrenia.

Psychopharmacologic treatment

The typical ID patient will already be on a number of psychotropic meds, so much of your job will be to evaluate current medications and judge which ones require adjustment. We typically ask family/staff for a timeline of medication trials. You’ll want to know what happened when each medication was started, and when the dosages were changed. It’s also useful to find out what was going on when patients were last doing well: Where were they living? What meds were they taking? Were they in school or working? It’s important to find out, for example, that three years ago a patient was doing very well.

Sometimes a regimen will have been stopped for no good reason. One patient came in on 25 medications, and eventually we found out she was previously stabilized on risperidone and valproate. However, a peer told her that risperidone caused weight gain, so she stopped taking it, even though she had never gained any weight while on the drug. She was tried on many other medications (resulting in polypharmacy) and never attained stability since the discontinuation of risperidone. Over time, we restarted the prior regimen with great results.

In terms of FDA approval, there are no medications approved specifically for patients with ID; nonetheless, many of the medications used for irritability or agitation in autism and other similar disorders are often effective.

Antipsychotics

If a patient’s issue is clearly psychosis, consider a low-dose second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) since these have lower risk of EPS. My go-to antipsychotics in this kind of situation include ziprasidone, aripiprazole, or lurasidone due to their better side effect profile, particularly regarding weight gain. We start at a low dose, and ask staff to carefully track behavior and specific symptoms. In our experience, it is best to put these instructions in writing on the doctor’s order form that most treatment program staff bring to each appointment. For example, if you’re starting a patient on aripiprazole 2 mg QAM, you’ll want to write on the form: “Track sedation, energy level, aggression, and work attendance daily for 30 days.” Since all written clinical orders are now documented, you can be assured that these behaviors will be tracked and the results brought to the next visit. Based on the results, you can choose to maintain the treatment, or you can increase the dose or frequency of dosing—for example, if you see a pattern of decompensation at specific times of day.

As an example of how difficult psychosis can be to assess, we once treated a patient with low-dose lurasidone for schizophrenia for over a year. His behavior was under control, and he had no obvious psychotic symptoms, but he began to consistently refuse to attend his assisted employment program for no clear reason that he could verbalize. One day, he attacked his uncle. In talking to the patient about what happened, it became clear that he was paranoid that people were plotting against him, including a man at his workshop who resembled his uncle. This delusion was the reason for non-adherence to his work program. Once we increased the dose of the SGA, he started going to work five days a week.

You decide to offer Anne treatment with a slow titration of aripiprazole, starting with 2 mg daily for 1 week then titrating to 5 mg for 1 week, before having her return to your office. You ask staff to observe Anne for any common side effects (akathisia, sleep alterations, increased anxiety, GI alterations, seizure, etc) and document behavioral changes. Before Anne leaves the office, you order baseline labs (CBC w/diff, HgbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting lipids, CMP, TSH, ANA, RF, H. pylori, vitamins D/B12 and folate) and perform an AIMS screen. One week later, a telephone check-in with staff reveals that Anne has not had any demonstrable side effects to the aripiprazole, and that she appears to be slightly less distracted; additionally, she has not had any further incidents of aggression toward her roommate. You recommend that staff continue with the titration and follow up in another week as previously planned. When Anne returns to the office, she appears to be back to her baseline and denies hearing any voices in the last week. You recommend continuing at the current dose and monitoring for any return of symptoms.

Mood stabilizers

Mood stabilizers can be quite helpful for agitation, and we will use valproate (our go-to) or low dose lithium (150 mg BID or TID; shoot for a level of 0.5 or 0.6 if possible to allow for variation in fluid intake). Oxcarbazepine isn’t traditionally our go-to, but we do occasionally use it. For example, we had a 25-year-old patient with moderate ID and bipolar disorder. She hadn’t tolerated antipsychotics in the past, and the family did not want her taking valproate or lithium (for various reasons), but they immediately agreed to oxcarbazepine 500 mg daily. It worked really well for her unstable moods and her obsessions. If mood stabilization is needed but the patient’s risk is less imminent, consider oxcarbazepine, topiramate, lamotrigine, or gabapentin. Use great caution when tapering anti-epileptic drugs, even if there is no history of seizure in the past; we’ve had patients seize for the first time when stopping these medications.

If patients are already taking an SGA or a mood stabilizer that was previously effective but their symptoms have returned, try adjusting the timing before increasing the total daily amount. For example, in a patient taking valproate 1500 mg at bedtime with a return of aggression, try ordering 500 mg TID before titrating up. Some behaviors will respond to these changes, the passage of time may reveal other factors, or the patient may independently show improvement.

Antidepressants/benzodiazepines

For depression and anxiety disorders, we consider SSRIs first, and our top two choices are sertraline or escitalopram for their benign side effect profile and lack of drug interactions. If these aren’t effective, you can try an SNRI or a novel antidepressant, but use extra caution with bupropion since it lowers the seizure threshold.

Be careful when using benzodiazepines; they can negatively impact memory, cognitive, and respiratory function. They may cause a paradoxical effect in patients with ID, leading to states of disinhibition, which can increase impulse control or problem behaviors. To rule out a paradoxical effect, ask the patient directly, “Have you ever received a medication before a dental procedure or imaging and had the opposite reaction of what you were hoping for?” If using benzos, we prefer low doses of the longer half-life options, such as clonazepam 0.25 mg QD or BID.

Adjunctive agents

If antipsychotics and mood stabilizers have been tried but prove ineffective, intolerable, or only partially effective, our next step would be to prescribe an alpha agonist, beta blocker, or naltrexone. We use clonidine or guanfacine, but at a low dose, and we prefer to prescribe once daily, either in the morning or at 3 PM. Ask your patient if symptoms are worse during daytime or evening hours, and have staff track progress for one month to gauge efficacy. If the medication is at 3 PM and only the evening hours are improved, you can add a morning dose. Most patients with ID have day programming, which is more structured. So, if you try a med in the AM and get good results, but the patient’s symptoms return in the afternoon, you can add a second dose to cover the remaining waking hours. If choosing a beta blocker, start low and go slow, using propranolol or betaxolol, and try to dose using the same timing schedule (3 AM and/or 3 PM). While naltrexone is approved only for alcoholism and opiate use disorder, there are also good data for a variety of impulsive disorders, including sexual aggression, skin picking, and overeating. Start with 25 mg, either 3 pm or 8 am, and you can go to BID, but don’t exceed 100 mg per day.

Other interventions

Don’t focus only on medications to fix everything—make sure to suggest other interventions too. There are multiple psychotherapeutic interventions that are modifiable for the ID population to treat mental health conditions. You can recommend a behavior support assessment for any problem behavior, and OT/PT/speech therapy/sensory assessments can assist with communication, functional limitations, sensory integration issues, and so on. Remember, you are not alone, but rather one part of a multidisciplinary team. Patients in their 20s who cannot communicate will get frustrated and will show us that they are struggling instead of telling us; don’t hesitate to order speech therapy, no matter the patient’s age. By asking about these extra interventions, you make the point that treatment will not be successful if it’s solely focused on medications.

As Freud said, “All behavior is purposeful.” Patients with ID show us their mental health symptoms; identifying them and providing effective treatment is an amazing experience. Imagine being the first person to connect with a patient and being able to help tell that patient’s story. Isn’t that what psychiatry is all about?

Once Anne has been stable on aripiprazole for a month, you decide to address her reluctance to talk to anyone about her symptoms as they were evolving. You order a speech therapy evaluation to evaluate any communication challenges, and you recommend that Anne start following up with a therapist to learn to identify and express her emotions more freely.

TCPR Verdict: For ID patients, communication problems can make assessment challenging. Ask lots of questions to staff and family as well as the patient, and insist on plenty of symptom monitoring to determine whether your choice of medication is actually effective.

General PsychiatryPrescribing psychotropic medications in patients with intellectual disability (ID) requires certain nuances in approach that may be unfamiliar to some psychiatrists. In this article, we’ll discuss some aspects of assessment and treatment that you may find useful when you encounter and work with such patients.

Assessment

1. Ask about psychosocial issues.

We usually begin by ruling out psychosocial causes of the behavior, because these issues can often be fixed without resorting to psychopharmaceuticals and their attendant side effects. Here are some of the more common issues in my experience.

- Staff turnover at group homes is very high; they are often like family to clients, and when staff members leave, this can be a great loss.

- Any changes to routine across any setting will often trigger behavioral responses in ID patients with poorly developed coping mechanisms and lower tolerance for change.

- Reminders, or anniversaries, of significant life events (such as past traumas or losses) may be the cause of the current issues; it takes ID patients longer to process change, and psychotherapy may be helpful.

- Family members not visiting or coming less frequently, or a parent developing an illness, can result in less contact between patients and their support network.

In response to your questions, the staff member reports that there were no changes in Anne’s family contact or routine. In addition, the group home changed the meal menu to items Anne prefers, increased her favorite activities, and reached out to family members, but nothing seems to have worked.

2. Ask about medical issues.

Because ID patients have difficulty communicating, they may have unrecognized medical symptoms affecting their mood and behavior.

- Medication changes. Patients with ID are more prone to adverse reactions from prescribed and OTC meds (especially antibiotics and antihistamines), which will often present as behavior problems.

- Common medical conditions. Ask about eating and drinking habits, bowel/bladder issues, and somatic complaints. ID patients frequently have behavior changes due to conditions such as GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease), seizure disorders, constipation, infectious disease (UTI, sinusitis, etc), and dental conditions.

When you ask about any medical issues Anne may have had, the staff member says that a recent visit to Anne’s PCP revealed no signs of infection or other medical problem that might have caused her agitation.

3. Assuming that there is a psychiatric cause of agitation, try to narrow down the underlying disorder.

- Anxiety and depression. These are very common and are often missed because the presenting symptoms are behavioral rather than the classic depressive/anxiety symptoms. A careful interview, while looking for observable signs of depression (eg, isolative behavior, crying, refusing to participate in favorite activities), can help.

-

Psychosis. It can be hard to distinguish psychosis from general behavior change related to the inherent issues with ID, such as concentration and attention span problems, or low frustration tolerance/impulsivity. And because of communication issues, ascertaining the presence of delusions or hallucinations can be a challenge. We sometimes have success asking specific and concrete questions, such as:

- Are you hearing people talk that you know or don’t know?

- Can you start or stop the talking?

- Are you feeling someone touch your skin who you can’t see?

- Are your eyes playing tricks on you?

- Does anything help? Is there anything that makes it worse?

During the interview with Anne, you ask her what happened with her roommate, and her reply is that “he told me to.” The staff reports that Anne’s roommate is female and that no males work in her group home. You notice that Anne seems to be periodically distracted throughout the interview, and you ask her if she knows who “he” is, to which she responds “no.” Further evaluation reveals that Anne has started to hear whispers intermittently. Her eventual diagnosis is schizophrenia.

Psychopharmacologic treatment

The typical ID patient will already be on a number of psychotropic meds, so much of your job will be to evaluate current medications and judge which ones require adjustment. We typically ask family/staff for a timeline of medication trials. You’ll want to know what happened when each medication was started, and when the dosages were changed. It’s also useful to find out what was going on when patients were last doing well: Where were they living? What meds were they taking? Were they in school or working? It’s important to find out, for example, that three years ago a patient was doing very well.

Sometimes a regimen will have been stopped for no good reason. One patient came in on 25 medications, and eventually we found out she was previously stabilized on risperidone and valproate. However, a peer told her that risperidone caused weight gain, so she stopped taking it, even though she had never gained any weight while on the drug. She was tried on many other medications (resulting in polypharmacy) and never attained stability since the discontinuation of risperidone. Over time, we restarted the prior regimen with great results.

In terms of FDA approval, there are no medications approved specifically for patients with ID; nonetheless, many of the medications used for irritability or agitation in autism and other similar disorders are often effective.

Antipsychotics

If a patient’s issue is clearly psychosis, consider a low-dose second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) since these have lower risk of EPS. My go-to antipsychotics in this kind of situation include ziprasidone, aripiprazole, or lurasidone due to their better side effect profile, particularly regarding weight gain. We start at a low dose, and ask staff to carefully track behavior and specific symptoms. In our experience, it is best to put these instructions in writing on the doctor’s order form that most treatment program staff bring to each appointment. For example, if you’re starting a patient on aripiprazole 2 mg QAM, you’ll want to write on the form: “Track sedation, energy level, aggression, and work attendance daily for 30 days.” Since all written clinical orders are now documented, you can be assured that these behaviors will be tracked and the results brought to the next visit. Based on the results, you can choose to maintain the treatment, or you can increase the dose or frequency of dosing—for example, if you see a pattern of decompensation at specific times of day.

As an example of how difficult psychosis can be to assess, we once treated a patient with low-dose lurasidone for schizophrenia for over a year. His behavior was under control, and he had no obvious psychotic symptoms, but he began to consistently refuse to attend his assisted employment program for no clear reason that he could verbalize. One day, he attacked his uncle. In talking to the patient about what happened, it became clear that he was paranoid that people were plotting against him, including a man at his workshop who resembled his uncle. This delusion was the reason for non-adherence to his work program. Once we increased the dose of the SGA, he started going to work five days a week.

You decide to offer Anne treatment with a slow titration of aripiprazole, starting with 2 mg daily for 1 week then titrating to 5 mg for 1 week, before having her return to your office. You ask staff to observe Anne for any common side effects (akathisia, sleep alterations, increased anxiety, GI alterations, seizure, etc) and document behavioral changes. Before Anne leaves the office, you order baseline labs (CBC w/diff, HgbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting lipids, CMP, TSH, ANA, RF, H. pylori, vitamins D/B12 and folate) and perform an AIMS screen. One week later, a telephone check-in with staff reveals that Anne has not had any demonstrable side effects to the aripiprazole, and that she appears to be slightly less distracted; additionally, she has not had any further incidents of aggression toward her roommate. You recommend that staff continue with the titration and follow up in another week as previously planned. When Anne returns to the office, she appears to be back to her baseline and denies hearing any voices in the last week. You recommend continuing at the current dose and monitoring for any return of symptoms.

Mood stabilizers

Mood stabilizers can be quite helpful for agitation, and we will use valproate (our go-to) or low dose lithium (150 mg BID or TID; shoot for a level of 0.5 or 0.6 if possible to allow for variation in fluid intake). Oxcarbazepine isn’t traditionally our go-to, but we do occasionally use it. For example, we had a 25-year-old patient with moderate ID and bipolar disorder. She hadn’t tolerated antipsychotics in the past, and the family did not want her taking valproate or lithium (for various reasons), but they immediately agreed to oxcarbazepine 500 mg daily. It worked really well for her unstable moods and her obsessions. If mood stabilization is needed but the patient’s risk is less imminent, consider oxcarbazepine, topiramate, lamotrigine, or gabapentin. Use great caution when tapering anti-epileptic drugs, even if there is no history of seizure in the past; we’ve had patients seize for the first time when stopping these medications.

If patients are already taking an SGA or a mood stabilizer that was previously effective but their symptoms have returned, try adjusting the timing before increasing the total daily amount. For example, in a patient taking valproate 1500 mg at bedtime with a return of aggression, try ordering 500 mg TID before titrating up. Some behaviors will respond to these changes, the passage of time may reveal other factors, or the patient may independently show improvement.

Antidepressants/benzodiazepines

For depression and anxiety disorders, we consider SSRIs first, and our top two choices are sertraline or escitalopram for their benign side effect profile and lack of drug interactions. If these aren’t effective, you can try an SNRI or a novel antidepressant, but use extra caution with bupropion since it lowers the seizure threshold.

Be careful when using benzodiazepines; they can negatively impact memory, cognitive, and respiratory function. They may cause a paradoxical effect in patients with ID, leading to states of disinhibition, which can increase impulse control or problem behaviors. To rule out a paradoxical effect, ask the patient directly, “Have you ever received a medication before a dental procedure or imaging and had the opposite reaction of what you were hoping for?” If using benzos, we prefer low doses of the longer half-life options, such as clonazepam 0.25 mg QD or BID.

Adjunctive agents

If antipsychotics and mood stabilizers have been tried but prove ineffective, intolerable, or only partially effective, our next step would be to prescribe an alpha agonist, beta blocker, or naltrexone. We use clonidine or guanfacine, but at a low dose, and we prefer to prescribe once daily, either in the morning or at 3 PM. Ask your patient if symptoms are worse during daytime or evening hours, and have staff track progress for one month to gauge efficacy. If the medication is at 3 PM and only the evening hours are improved, you can add a morning dose. Most patients with ID have day programming, which is more structured. So, if you try a med in the AM and get good results, but the patient’s symptoms return in the afternoon, you can add a second dose to cover the remaining waking hours. If choosing a beta blocker, start low and go slow, using propranolol or betaxolol, and try to dose using the same timing schedule (3 AM and/or 3 PM). While naltrexone is approved only for alcoholism and opiate use disorder, there are also good data for a variety of impulsive disorders, including sexual aggression, skin picking, and overeating. Start with 25 mg, either 3 pm or 8 am, and you can go to BID, but don’t exceed 100 mg per day.

Other interventions

Don’t focus only on medications to fix everything—make sure to suggest other interventions too. There are multiple psychotherapeutic interventions that are modifiable for the ID population to treat mental health conditions. You can recommend a behavior support assessment for any problem behavior, and OT/PT/speech therapy/sensory assessments can assist with communication, functional limitations, sensory integration issues, and so on. Remember, you are not alone, but rather one part of a multidisciplinary team. Patients in their 20s who cannot communicate will get frustrated and will show us that they are struggling instead of telling us; don’t hesitate to order speech therapy, no matter the patient’s age. By asking about these extra interventions, you make the point that treatment will not be successful if it’s solely focused on medications.

As Freud said, “All behavior is purposeful.” Patients with ID show us their mental health symptoms; identifying them and providing effective treatment is an amazing experience. Imagine being the first person to connect with a patient and being able to help tell that patient’s story. Isn’t that what psychiatry is all about?

Once Anne has been stable on aripiprazole for a month, you decide to address her reluctance to talk to anyone about her symptoms as they were evolving. You order a speech therapy evaluation to evaluate any communication challenges, and you recommend that Anne start following up with a therapist to learn to identify and express her emotions more freely.

TCPR Verdict: For ID patients, communication problems can make assessment challenging. Ask lots of questions to staff and family as well as the patient, and insist on plenty of symptom monitoring to determine whether your choice of medication is actually effective.

Some Monitoring and Treatment Suggestions for ID Patients

- Do metabolic monitoring (HgbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting lipids) at least twice annually and more often if there are multiple medical or neurological conditions. ID patients may not be able to exercise, so they are at higher risk of metabolic side effects with medications such as olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine.

- Consider expanded lab work, including a standard intake panel (CBC, electrolytes, liver function test) as well as annual rheumatoid factor, ANA, vitamin levels (including Vitamin D, B12, and folate), and H. pylori (patients with ID have higher rates of H. pylori than the general population).

- Do an AIMS scale (or your favorite standardized screen for EPS) at least twice yearly, or more often if the patient has a diagnosed EPS condition, a history of EPS, or a muscular disorder such as cerebral palsy.

- Patients with ID are more vulnerable to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and the fatality rate is higher in ID patients.

- Use extra caution with any medications that affect the seizure threshold (clozapine, anticholinergics, antihistamines, phenothiazines, bupropion, etc).

- Take into account difficulty with pill swallowing, as dysphagia is common; consider alternate preparations (liquids, dissolvables, etc).

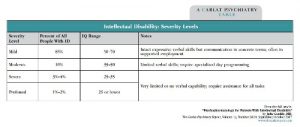

Table: Intellectual Disability Severity Levels

(Click here to view as full sized PDF.)

Issue Date: September 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)