Home » Coffee: Healthy Study Aid or the Addiction We Hate to Acknowledge?

Coffee: Healthy Study Aid or the Addiction We Hate to Acknowledge?

January 1, 2019

From The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report

Rehan Aziz, MD.

Associate professor of psychiatry and neurology, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine.

Dr. Aziz has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Caffeine permeates our society. It comes in many forms, including coffee and increasingly popular energy drinks. We consume it, and so do our patients. So, is it a harmless habit or a potentially harmful addiction? Let’s take a sip and find out.

Is it addictive?

The WHO in ICD-10 recognizes the diagnosis of substance dependence due to caffeine, and the DSM-5 has listed caffeine use disorder under “Conditions for Further Study.” In order to qualify for the diagnosis of caffeine use disorder, individuals must meet all of the following criteria: attempts to regulate their intake, continued use despite negative physical or psychological consequences, and a history of caffeine withdrawal.

The prevalence of caffeine use disorder in the population is estimated to be around 9%, making it more common than we might think. Even in the absence of a formal diagnosis, caffeine use may be clinically distressing for many, and up to 14% of the public continues to consume caffeine despite developing adverse physical and psychological consequences (Meredith SE et al, J Caffeine Research 2013;3(3):114–130).

Is it risky?

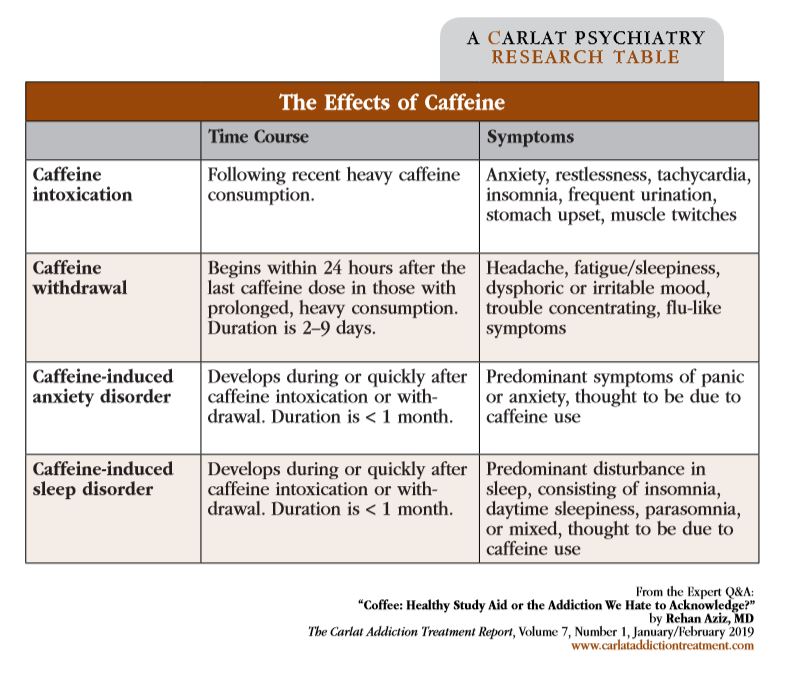

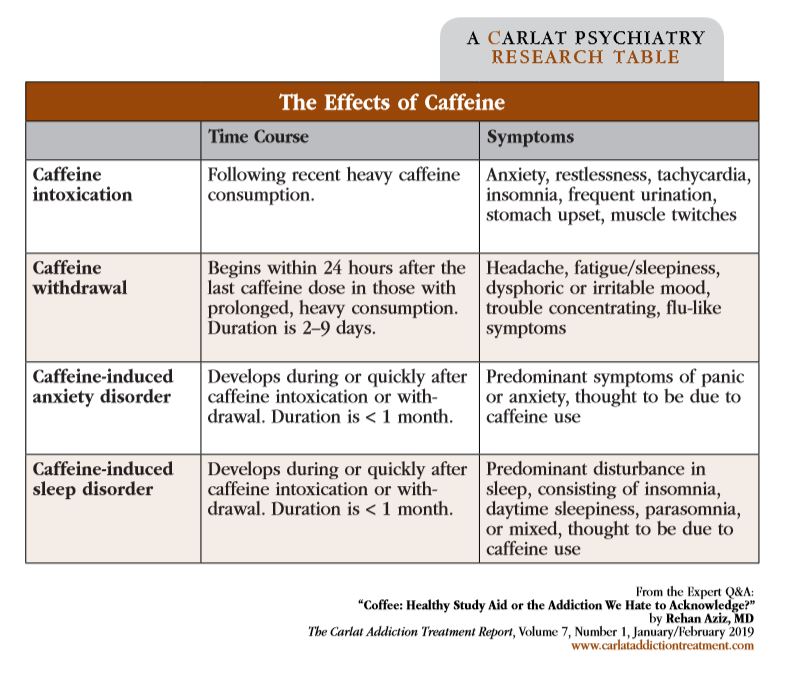

The DSM-5 specifies four caffeine-related disorders: caffeine intoxication, caffeine withdrawal, caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, and caffeine-induced sleep disorder. (See the table below on “The Effects of Caffeine.”) For reference, 85% of the U.S. population consumes at least 1 caffeinated beverage per day, and the average daily caffeine intake from all beverages is 186 mg for all ages combined. One cup of coffee contains 50–100 mg of caffeine. A can of soda has 40 mg of caffeine. Energy drinks have up to 500 mg in a single can! To look up the caffeine content of specific products, check out this resource.

Beyond the discrete DSM-5 disorders, caffeine can increase anxiety symptoms in those with panic disorder, GAD, or social anxiety disorder. In high doses, it may precipitate mania or psychosis, although in our experience this is very rare. Some large epidemiological studies have found a correlation between very high coffee use (greater than 8 cups per day) and an increased risk of suicide (Tanskanen A et al, Eur J Epidemiol 2000;16(9):789–791), while other studies have linked 2–6 cups per day and a lower risk of suicide (Lucas M et al, World J Biol Psychiatry 2014;15(5):377–386). Finally, in any patient with caffeine use disorder, you should also screen for daily cigarette smoking and alcohol use disorder, since these conditions often run together.

Caffeine has been linked to concerning medical outcomes. Toxic doses have been associated with serious events, like cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and death. It is especially dangerous when combined with alcohol, as the mixture can lead to rapid and severe intoxication. As a result, the FDA began taking action on combo drinks such as Four Loko in 2010. Caffeine can also increase total cholesterol and LDL, as well as cause elevations in blood pressure and variations in heart rate. Coffee can worsen GERD, though this is controversial and may be due to other coffee constituents beyond just caffeine (Grosso G et al, Ann Rev Nutr 2017;37:131–156).

In pregnant women, caffeine crosses the placenta and reaches levels in the fetus similar to the mother’s. When large amounts are ingested, this can cause spontaneous abortions, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, and preterm delivery. You should recommend that reproductive-age women consume less than 300 mg caffeine per day, if they consume any at all (Kuczkowski KM, Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:695). Caffeine also increases calcium excretion and may be a risk factor for osteoporosis, especially in women with low calcium but high caffeine intake (Hallström H et al, Osteoporos Int 2006;17(7):1055–1064).

Is it good for you?

Coffee has some potential health benefits. For example, in men and women, moderate coffee consumption (1–2 cups per day) or high decaf coffee consumption (2–4 cups per day) were associated with reduced total mortality (Je Y et al, Br J Nutr 2014;111(7):1162–1173). Other studies have linked coffee with decreased risk of a variety of diseases, including cancer and heart disease (Grosso G et al, Ann Rev Nutr 2017;37:131–156). A major limitation of coffee research, though, is that most of the data come solely from observing coffee drinkers. Only a few studies are RCTs, the gold standard, which makes these findings subject to change.

Does it enhance performance?

Coffee drinkers swear that java improves functioning, but is this due to caffeine or placebo? It seems that caffeine is in fact effective for improving physical and cognitive functioning in rested or fatigued individuals. Low (40 mg) to moderate (300 mg) amounts improve cognition in a dose-dependent manner. Caffeine also improves attention, vigilance, and reaction times, but doses above 400 mg are more likely to cause anxiety and could actually impede performance.

Caffeine’s most reliable impact is on vigilance: sustaining performance on long, boring, or monotonous tasks. Amounts in the 200 mg range improve functioning for several hours. This same effect, with 200–300 mg, is seen in sleep-deprived individuals. Otherwise, studies show caffeine has little impact on complex judgment, risky decision-making, and possibly short-term memory (McLellan TM et al, Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;71:294–312).

CATR Verdict: A cup or two of coffee a day may keep the doctors away; more than four cups may call them back. For the majority of our patients (and us), the benefits of coffee will likely outweigh the risks, but for a small subset, it can have a negative impact.

Addiction TreatmentIs it addictive?

The WHO in ICD-10 recognizes the diagnosis of substance dependence due to caffeine, and the DSM-5 has listed caffeine use disorder under “Conditions for Further Study.” In order to qualify for the diagnosis of caffeine use disorder, individuals must meet all of the following criteria: attempts to regulate their intake, continued use despite negative physical or psychological consequences, and a history of caffeine withdrawal.

The prevalence of caffeine use disorder in the population is estimated to be around 9%, making it more common than we might think. Even in the absence of a formal diagnosis, caffeine use may be clinically distressing for many, and up to 14% of the public continues to consume caffeine despite developing adverse physical and psychological consequences (Meredith SE et al, J Caffeine Research 2013;3(3):114–130).

Is it risky?

The DSM-5 specifies four caffeine-related disorders: caffeine intoxication, caffeine withdrawal, caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, and caffeine-induced sleep disorder. (See the table below on “The Effects of Caffeine.”) For reference, 85% of the U.S. population consumes at least 1 caffeinated beverage per day, and the average daily caffeine intake from all beverages is 186 mg for all ages combined. One cup of coffee contains 50–100 mg of caffeine. A can of soda has 40 mg of caffeine. Energy drinks have up to 500 mg in a single can! To look up the caffeine content of specific products, check out this resource.

Beyond the discrete DSM-5 disorders, caffeine can increase anxiety symptoms in those with panic disorder, GAD, or social anxiety disorder. In high doses, it may precipitate mania or psychosis, although in our experience this is very rare. Some large epidemiological studies have found a correlation between very high coffee use (greater than 8 cups per day) and an increased risk of suicide (Tanskanen A et al, Eur J Epidemiol 2000;16(9):789–791), while other studies have linked 2–6 cups per day and a lower risk of suicide (Lucas M et al, World J Biol Psychiatry 2014;15(5):377–386). Finally, in any patient with caffeine use disorder, you should also screen for daily cigarette smoking and alcohol use disorder, since these conditions often run together.

Caffeine has been linked to concerning medical outcomes. Toxic doses have been associated with serious events, like cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and death. It is especially dangerous when combined with alcohol, as the mixture can lead to rapid and severe intoxication. As a result, the FDA began taking action on combo drinks such as Four Loko in 2010. Caffeine can also increase total cholesterol and LDL, as well as cause elevations in blood pressure and variations in heart rate. Coffee can worsen GERD, though this is controversial and may be due to other coffee constituents beyond just caffeine (Grosso G et al, Ann Rev Nutr 2017;37:131–156).

In pregnant women, caffeine crosses the placenta and reaches levels in the fetus similar to the mother’s. When large amounts are ingested, this can cause spontaneous abortions, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, and preterm delivery. You should recommend that reproductive-age women consume less than 300 mg caffeine per day, if they consume any at all (Kuczkowski KM, Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:695). Caffeine also increases calcium excretion and may be a risk factor for osteoporosis, especially in women with low calcium but high caffeine intake (Hallström H et al, Osteoporos Int 2006;17(7):1055–1064).

Is it good for you?

Coffee has some potential health benefits. For example, in men and women, moderate coffee consumption (1–2 cups per day) or high decaf coffee consumption (2–4 cups per day) were associated with reduced total mortality (Je Y et al, Br J Nutr 2014;111(7):1162–1173). Other studies have linked coffee with decreased risk of a variety of diseases, including cancer and heart disease (Grosso G et al, Ann Rev Nutr 2017;37:131–156). A major limitation of coffee research, though, is that most of the data come solely from observing coffee drinkers. Only a few studies are RCTs, the gold standard, which makes these findings subject to change.

Does it enhance performance?

Coffee drinkers swear that java improves functioning, but is this due to caffeine or placebo? It seems that caffeine is in fact effective for improving physical and cognitive functioning in rested or fatigued individuals. Low (40 mg) to moderate (300 mg) amounts improve cognition in a dose-dependent manner. Caffeine also improves attention, vigilance, and reaction times, but doses above 400 mg are more likely to cause anxiety and could actually impede performance.

Caffeine’s most reliable impact is on vigilance: sustaining performance on long, boring, or monotonous tasks. Amounts in the 200 mg range improve functioning for several hours. This same effect, with 200–300 mg, is seen in sleep-deprived individuals. Otherwise, studies show caffeine has little impact on complex judgment, risky decision-making, and possibly short-term memory (McLellan TM et al, Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;71:294–312).

CATR Verdict: A cup or two of coffee a day may keep the doctors away; more than four cups may call them back. For the majority of our patients (and us), the benefits of coffee will likely outweigh the risks, but for a small subset, it can have a negative impact.

Issue Date: January 1, 2019

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)