Home » Practical Approaches to Vetting Clinical Research

Practical Approaches to Vetting Clinical Research

June 11, 2019

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Darren B. Courtney, MD, FRCPC

Darren B. Courtney, MD, FRCPC

Staff Psychiatrist for the Youth Addictions and Concurrent Disorders Service at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Dr. Courtney has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CCPR: Tell us a bit about your current work. What is your population? Whom do you treat?

Dr. Courtney: My clinical population are patients with concurrent addictions and mental health issues. These patients present complex clinical challenges, and so I have made efforts to use a method to think about and sort through those problems.

CCPR: Please share with us the method that you prefer to use to efficiently frame clinical questions.

Dr. Courtney: Sure. It’s called the PICOT method. The idea here is that you need to narrow your literature search down to your specific clinical case. The “P” stands for population—specifically, the age groups, the overall condition of the population (diagnostic, socioeconomic, etc), and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The “I” stands for intervention: the intervention of interest that you’re looking for in the clinical literature. Often, it’s related to medication or specific psychosocial intervention (Riva JJ et al, J Can Chiropr Assoc 2012;56(3):167–171).

CCPR: I’ve heard some people spell it PECOT instead of PICOT.

Dr. Courtney: Right. If it’s an observational study, you might spell it PECOT, with the “E” standing for exposure. For example, if you’re interested in knowing if trauma increases the risk of depression or substance use, then the study involves an exposure instead of an intervention. The “C” stands for comparison: You might be interested in comparing the intervention to a wait list, to treatment as usual, or to another active intervention. The “O” stands for outcomes: What’s the primary outcome that you’re interested in? It could be symptom reduction, or better functioning, or many other things. And lastly, the “T” stands for timing: the time course over which you’re expecting to see the outcomes for your clinical question.

CCPR: How can this method help in everyday clinical life to clarify our thinking about a patient?

Dr. Courtney: The idea is to apply the evidence we have to our clinical presentations and then see how research studies apply. By framing your clinical question in this PICOT format, it’s easier to see which studies might apply to your question, or to what extent they might apply. PICOT helps frame the clinical question in a way that makes it easier to search through literature, to know what’s relevant or not relevant for your question.

CCPR: Do you have a specific example of how you would use the PICOT method?

Dr. Courtney: Sure. Say a child shows up with symptoms of ADHD. It’s common for parents to ask whether there are any effective non-pharmacological interventions or even nutraceuticals like omega-3s. Using the PICOT method, you would start by asking about the population. So what age range is this child: prepubescent, pubescent, or adolescent? There are likely to be different papers on each of those age groups, and also on various presentations, such as ADHD combined type or inattentive symptoms only.

CCPR: That already narrows down our literature search considerably.

Dr. Courtney: Right. And then what is the intervention of interest—say, psychosocial interventions or specific psychotherapies, like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or parent training? Which of those might you want to look at more specifically? Now, what do you want as the comparison group? Another treatment, perhaps treatment as usual for this kind of problem in this population in this community? Or perhaps comparing it with no treatment? Then there’s the outcome: What specifically? Are you looking for decreases in aggression? Are you looking for improvement in school functioning? Are you looking for decreases in ADHD symptoms as your primary outcome? Lastly, are you hoping for an outcome within a certain amount of time?

CCPR: Right, I wondered about that.

Dr. Courtney: Yes. Typically, with stimulants you might see a pretty rapid improvement; but with psychosocial interventions, you might expect something to take more like 3 months or 6 months. So, the PICOT format makes it easier to do your search; when various studies come up, or even meta-analyses or systematic reviews or clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), you can apply the specific question and look for your answer in a more focused way. This is far better than doing a general search on psychosocial interventions for ADHD, which is too broad of a topic.

CCPR: You’ve mentioned several types of resources: studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, CPGs. What are the best kinds of studies for busy clinicians to look at? Is there a hierarchy that you suggest?

Dr. Courtney: We recommend relying on good CPGs first and foremost. That said, there’s a large variety of CPGs out there, and they’re of varying quality. Our group has done a systematic review of CPGs for depression and anxiety, and we are currently working on one for ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders. We have found only a select few that meet a high standard, so it’s important to understand what makes a quality guideline.

CCPR: What if there are gaps in the literature?

Dr. Courtney: That’s pretty common. When that happens, a good CPG uses methods to arrive at consensus among experts. High-quality CPGs also incorporate feedback from family members, from caregivers, and from people who’ve struggled with the disorder in question.

CCPR: What if there isn’t a high-quality CPG to turn to?

Dr. Courtney: Then we move on to meta-analyses, which synthesize multiple studies and pool the information and data in such a way that we can estimate the effects a specific treatment has relative to the comparison group. And if that’s not available, you can go with the primary randomized controlled trials (RCTs); in many cases, that’s all we have for various PICOT questions. But we have to be careful with that, because often one randomized trial is done and shows one result, but then another randomized trial is done and shows a very different result. So we have to be wary about just counting on results from one study.

CCPR: And systematic reviews are not quite as valuable as meta-analyses, but more valuable than one or two RCTs, right?

Dr. Courtney: Yes. Systematic reviews would come in between meta-analyses and individual RCTs. The downside is that they don’t pool the data. Sometimes studies are so different that pooling data makes no sense and it is better to do a systematic review, which describes what data are out there.

CCPR: In child and adolescent psychiatry, we often don’t have the studies that we want, which is why confirmation studies are critical. Would you concur that if you don’t have much else, a second RCT adds a lot more certainty versus just having one?

Dr. Courtney: Yes, I would agree with that. Having at least two RCTs is required to be considered Level 1 evidence or Level A evidence, depending on which system you’re using (https://tinyurl.com/yxzabd3z). We can feel more confident with the results if they’re replicated in two RCTs.

CCPR: If two RCTs is an A, what would constitute a B?

Dr. Courtney: Level B (or Level 2) is if there’s one RCT. There is a mood and anxiety disorders guideline system in Canada, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT), that has different criteria than the UK’s National Institute of Clinical and Health Excellence (NICE) guidelines or the APA guidelines. Each of them uses slightly different methods to assess their evidence. But a top level of evidence requires at least two RCTs.

CCPR: Right, and with the advent of required registration and reporting of clinical trials, we are seeing publication of negative trials, like the two negative RCT trials on desvenlafaxine for depression in children.

Dr. Courtney: I think it’s a great effort to try and make sure that we’re publishing negative as well as positive trials.

CCPR: Do you have go-to sources for CPGs and other good data to assess clinical questions?

Dr. Courtney: NICE in the UK is consistently high quality and is a good place to start (https://www.nice.org.uk). They do systematic reviews on the relevant PICOT questions, as well as focus groups with people who have struggled with a disorder or with their caregivers. They do a good job of linking the evidence to the clinical questions. Next, I often look at Cochrane Reviews because I know their methods are sound (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/about-cdsr). However, Cochrane Reviews often say that the results are inconclusive, and then we’re left without guidance. Still, if they do find a conclusive result, then we can be sure that that’s been well-studied. The US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also does good meta-analyses or systematic reviews (https://www.ahrq.gov). I’m constantly scanning literature, including interesting RCTs, but if I’m looking for the broad consensus on a specific topic, I’ll look at those three sources.

CCPR: Hopefully, after this, our readers will be able to ask clearer questions and know where to go for decent information. But, of course, sometimes we just don’t have the answers. What do you tell families or patients when we don’t have the information we’d like?

Dr. Courtney: I work in a tertiary care center where patients have tried all of the evidence-based options that we have—often patients with treatment-resistant depression who’ve tried fluoxetine, sertraline, and then CBT. That’s what we have in terms of robust information. The next-line attempt will depend on my formulation, and it comes with a disclosure that although it may be helpful, we’re working with limited information. I reassure them that we’re going to continue to monitor to see if it helps, and if not, we’re going to switch things around and see where things go.

CCPR: This has been really helpful. Any other thoughts?

Dr. Courtney: We’re currently looking at integrated care pathways, where you take the guideline recommendations and put them into a treatment algorithm. Our depression clinic for adolescents is implementing this as a default protocol. Of course, clinicians are still always allowed to make their own clinical decisions. We’re examining that now in research and seeing where that goes.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Courtney.

Child PsychiatryDr. Courtney: My clinical population are patients with concurrent addictions and mental health issues. These patients present complex clinical challenges, and so I have made efforts to use a method to think about and sort through those problems.

CCPR: Please share with us the method that you prefer to use to efficiently frame clinical questions.

Dr. Courtney: Sure. It’s called the PICOT method. The idea here is that you need to narrow your literature search down to your specific clinical case. The “P” stands for population—specifically, the age groups, the overall condition of the population (diagnostic, socioeconomic, etc), and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The “I” stands for intervention: the intervention of interest that you’re looking for in the clinical literature. Often, it’s related to medication or specific psychosocial intervention (Riva JJ et al, J Can Chiropr Assoc 2012;56(3):167–171).

CCPR: I’ve heard some people spell it PECOT instead of PICOT.

Dr. Courtney: Right. If it’s an observational study, you might spell it PECOT, with the “E” standing for exposure. For example, if you’re interested in knowing if trauma increases the risk of depression or substance use, then the study involves an exposure instead of an intervention. The “C” stands for comparison: You might be interested in comparing the intervention to a wait list, to treatment as usual, or to another active intervention. The “O” stands for outcomes: What’s the primary outcome that you’re interested in? It could be symptom reduction, or better functioning, or many other things. And lastly, the “T” stands for timing: the time course over which you’re expecting to see the outcomes for your clinical question.

CCPR: How can this method help in everyday clinical life to clarify our thinking about a patient?

Dr. Courtney: The idea is to apply the evidence we have to our clinical presentations and then see how research studies apply. By framing your clinical question in this PICOT format, it’s easier to see which studies might apply to your question, or to what extent they might apply. PICOT helps frame the clinical question in a way that makes it easier to search through literature, to know what’s relevant or not relevant for your question.

CCPR: Do you have a specific example of how you would use the PICOT method?

Dr. Courtney: Sure. Say a child shows up with symptoms of ADHD. It’s common for parents to ask whether there are any effective non-pharmacological interventions or even nutraceuticals like omega-3s. Using the PICOT method, you would start by asking about the population. So what age range is this child: prepubescent, pubescent, or adolescent? There are likely to be different papers on each of those age groups, and also on various presentations, such as ADHD combined type or inattentive symptoms only.

CCPR: That already narrows down our literature search considerably.

Dr. Courtney: Right. And then what is the intervention of interest—say, psychosocial interventions or specific psychotherapies, like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or parent training? Which of those might you want to look at more specifically? Now, what do you want as the comparison group? Another treatment, perhaps treatment as usual for this kind of problem in this population in this community? Or perhaps comparing it with no treatment? Then there’s the outcome: What specifically? Are you looking for decreases in aggression? Are you looking for improvement in school functioning? Are you looking for decreases in ADHD symptoms as your primary outcome? Lastly, are you hoping for an outcome within a certain amount of time?

CCPR: Right, I wondered about that.

Dr. Courtney: Yes. Typically, with stimulants you might see a pretty rapid improvement; but with psychosocial interventions, you might expect something to take more like 3 months or 6 months. So, the PICOT format makes it easier to do your search; when various studies come up, or even meta-analyses or systematic reviews or clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), you can apply the specific question and look for your answer in a more focused way. This is far better than doing a general search on psychosocial interventions for ADHD, which is too broad of a topic.

CCPR: You’ve mentioned several types of resources: studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, CPGs. What are the best kinds of studies for busy clinicians to look at? Is there a hierarchy that you suggest?

Dr. Courtney: We recommend relying on good CPGs first and foremost. That said, there’s a large variety of CPGs out there, and they’re of varying quality. Our group has done a systematic review of CPGs for depression and anxiety, and we are currently working on one for ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders. We have found only a select few that meet a high standard, so it’s important to understand what makes a quality guideline.

CCPR: What if there are gaps in the literature?

Dr. Courtney: That’s pretty common. When that happens, a good CPG uses methods to arrive at consensus among experts. High-quality CPGs also incorporate feedback from family members, from caregivers, and from people who’ve struggled with the disorder in question.

CCPR: What if there isn’t a high-quality CPG to turn to?

Dr. Courtney: Then we move on to meta-analyses, which synthesize multiple studies and pool the information and data in such a way that we can estimate the effects a specific treatment has relative to the comparison group. And if that’s not available, you can go with the primary randomized controlled trials (RCTs); in many cases, that’s all we have for various PICOT questions. But we have to be careful with that, because often one randomized trial is done and shows one result, but then another randomized trial is done and shows a very different result. So we have to be wary about just counting on results from one study.

CCPR: And systematic reviews are not quite as valuable as meta-analyses, but more valuable than one or two RCTs, right?

Dr. Courtney: Yes. Systematic reviews would come in between meta-analyses and individual RCTs. The downside is that they don’t pool the data. Sometimes studies are so different that pooling data makes no sense and it is better to do a systematic review, which describes what data are out there.

CCPR: In child and adolescent psychiatry, we often don’t have the studies that we want, which is why confirmation studies are critical. Would you concur that if you don’t have much else, a second RCT adds a lot more certainty versus just having one?

Dr. Courtney: Yes, I would agree with that. Having at least two RCTs is required to be considered Level 1 evidence or Level A evidence, depending on which system you’re using (https://tinyurl.com/yxzabd3z). We can feel more confident with the results if they’re replicated in two RCTs.

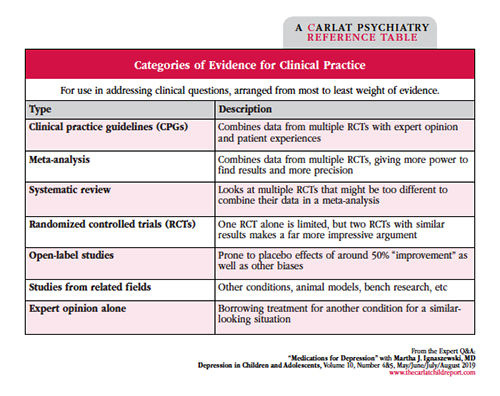

Table: Categories of Evidence for Clinical Practice

Click for full-size PDF.

CCPR: If two RCTs is an A, what would constitute a B?

Dr. Courtney: Level B (or Level 2) is if there’s one RCT. There is a mood and anxiety disorders guideline system in Canada, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT), that has different criteria than the UK’s National Institute of Clinical and Health Excellence (NICE) guidelines or the APA guidelines. Each of them uses slightly different methods to assess their evidence. But a top level of evidence requires at least two RCTs.

CCPR: Right, and with the advent of required registration and reporting of clinical trials, we are seeing publication of negative trials, like the two negative RCT trials on desvenlafaxine for depression in children.

Dr. Courtney: I think it’s a great effort to try and make sure that we’re publishing negative as well as positive trials.

CCPR: Do you have go-to sources for CPGs and other good data to assess clinical questions?

Dr. Courtney: NICE in the UK is consistently high quality and is a good place to start (https://www.nice.org.uk). They do systematic reviews on the relevant PICOT questions, as well as focus groups with people who have struggled with a disorder or with their caregivers. They do a good job of linking the evidence to the clinical questions. Next, I often look at Cochrane Reviews because I know their methods are sound (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/about-cdsr). However, Cochrane Reviews often say that the results are inconclusive, and then we’re left without guidance. Still, if they do find a conclusive result, then we can be sure that that’s been well-studied. The US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also does good meta-analyses or systematic reviews (https://www.ahrq.gov). I’m constantly scanning literature, including interesting RCTs, but if I’m looking for the broad consensus on a specific topic, I’ll look at those three sources.

CCPR: Hopefully, after this, our readers will be able to ask clearer questions and know where to go for decent information. But, of course, sometimes we just don’t have the answers. What do you tell families or patients when we don’t have the information we’d like?

Dr. Courtney: I work in a tertiary care center where patients have tried all of the evidence-based options that we have—often patients with treatment-resistant depression who’ve tried fluoxetine, sertraline, and then CBT. That’s what we have in terms of robust information. The next-line attempt will depend on my formulation, and it comes with a disclosure that although it may be helpful, we’re working with limited information. I reassure them that we’re going to continue to monitor to see if it helps, and if not, we’re going to switch things around and see where things go.

CCPR: This has been really helpful. Any other thoughts?

Dr. Courtney: We’re currently looking at integrated care pathways, where you take the guideline recommendations and put them into a treatment algorithm. Our depression clinic for adolescents is implementing this as a default protocol. Of course, clinicians are still always allowed to make their own clinical decisions. We’re examining that now in research and seeing where that goes.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Courtney.

KEYWORDS adolescents children clinical-practice inquiry pediatric picot practice_tools_and_tips research teens

Issue Date: June 11, 2019

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)