Home » A Pragmatic Approach to Borderline Personality Disorder

EXPERT Q&A

A Pragmatic Approach to Borderline Personality Disorder

June 10, 2020

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Lois Choi-Kain, MEd, MD

Lois Choi-Kain, MEd, MD

Director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute at McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA. Co-editor of Applications of Good Psychiatric Management for Borderline Personality Disorders: A Practical Guide (APA, 2019) with the late John Gunderson, MD (1942–2019).

Dr. Choi-Kain has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: Tell us about this new approach to borderline personality disorder (BPD): good psychiatric management.

Dr. Choi-Kain: We have many effective therapies for BPD. There’s dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), transference-focused therapy, and mentalization-based therapy. Good psychiatric management borrows from the other approaches, but differs in that it developed out of clinical experience rather than a theoretical model, so it’s easier for general psychiatrists to adopt. This approach was actually used as the placebo arm that DBT was compared to, and in some respects it worked as well as DBT. Its effects were comparable in terms of reducing self-harm and suicidality, as well as many of the core symptoms in the diagnostic criteria for BPD (McMain SF et al, Am J Psychiatry 2009;166(12):1365–1374).

TCPR: Walk us through the steps of good psychiatric management.

Dr. Choi-Kain: The approach is very direct and collaborative. We explain the diagnosis and help the patient understand how it plays out in their life. We help them identify goals and plan the treatment around those goals. The goals might include symptom reduction, but we try to focus on functioning and broader life goals, like getting a job or establishing more stable friendships. We want them to develop a life outside of treatment. The message is, “You’re more than a patient. You’re someone who has ambitions outside of just getting better.” These are elements of good psychiatric management for any disorder, from depression to substance use. One thing we’ve learned about the natural course of BPD is that functioning remains fairly impaired for the majority of patients, even when their symptoms improve.

TCPR: Many of the core symptoms of BPD touch on functioning, like unstable relationships and impulsivity, so I’m surprised that functioning doesn’t improve as the symptoms get better.

Dr. Choi-Kain: Well, nobody really knows why that is, but it suggests that focusing on core symptoms of BPD may not be enough to help patients navigate the world better. We have a mantra in this work: “Get a life or get a job.” We want our patients to get a job so they can have a steady place to be, with a regular schedule and well-defined roles. People with BPD need a stable way to be with others. At the end of the day, that’s what they are looking for, and yet they are naturally drawn into intense exclusive relationships where there is no template and no structure. Likewise, there must be clear roles in the treatment so that everything is predicable and has a firm outline to it.

TCPR: And if they can’t find a job?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Any structured social activity could serve the same purpose. College, vocational rehab, church, an exercise group, or a 12-step program. We want them to be part of a community. We don’t want them to develop an exclusive, dependent relationship on the treatment program.

TCPR: What are some typical goals that patients with BPD bring to the table?

Dr. Choi-Kain: They might want to have more independence, or more credibility with others. That would be the long-term goal, and then we’d break it down into short-term, concrete steps. You might say, “I can really understand that you would want your parents to give you the freedom to make your own decisions. What things might you need to do in order to make that happen?” Some of the steps might involve being less reactive, more consistent, and more self-reliant in their day-to-day lives. The art is in translating those goals into specific behavioral changes that are measurable and achievable—for example, “I will develop a monthly budget and spend within my means so I don’t have to borrow money.”

TCPR: Can you do this kind of work when you’re seeing the patient once a month for half an hour?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Absolutely. You can do this with any frequency of meetings. It’s actually more realistic to assess a patient’s progress toward goals over monthly visits because these changes take time to develop.

TCPR: How do you handle this scenario? A patient with BPD moved from another state and is now seeing you for the first time. They are on several medications that they swear by: a stimulant, a benzo, an antipsychotic, a sleep med, and an antidepressant. You suspect some of those might be causing harm.

Dr. Choi-Kain: I’d recommend a collaborative approach that’s based on a rational set of decisions around the medications. First, you’d want to get to know the patient better. Understand their goals and how they see their problems, and tie the treatment to those goals. That takes time, and unless the medications present an imminent danger, you’d want to give them a fair shot at it. If you do change the medications, you’d want that to be a collaborative process. Educate them about the evidence and the risks, and clarify your own limitations around prescriptions in an honest way. You want the patient to feel like the treatment is being done with them, not to them.

TCPR: What are your top dos and don’ts for communicating with patients with BPD?

Dr. Choi-Kain: The top dos are to be honest and direct. The natural tendency is to be too careful about what’s said and “walk on eggshells” because people with BPD are very sensitive. That doesn’t work well, because they also happen to be sensitive to body language, so they can pick up on disingenuousness. Well-meaning people often try to cover up their own negativity by being overly nice, but that ultimately harms the patient’s ability to trust them. In good psychiatric management, we respect the patient and believe they can manage what we have to say. If they get upset about it, we try to understand their reaction.

TCPR: I’ve heard that patients with BPD misread facial expressions. How does that play out in treatment?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Yes, they have particular difficulty with neutral faces. They don’t do well with ambiguity. So the traditional “blank slate” is not going to work here. They also tend to be better at reading negative faces than others and are more sensitive to negative expressions (Mitchell AE et al, Neuropsychol Rev 2014;24:166–184). People with BPD need to know where you stand, so we avoid vague expressions. Whether it’s verbal or nonverbal, we try to communicate openly and clearly.

TCPR: Some people advise to “strike while the iron is cold” when confronting difficult subjects with patients who have BPD.

Dr. Choi-Kain: I’d phrase that differently. Patients with BPD want to know what is on your mind, whether the temperature is hot or cold. They may want to know more when the temperature is hot. That’s because heated emotions often rise up when the patient feels that their connection to you has been threatened. We teach patients that their BPD symptoms tend to fluctuate with the level of engagement they have with significant others. When they feel connected and secure in their relationship, they tend to be very collaborative. But they are also sensitive to signs of rejection or disapproval. When their connection feels threatened, the emotions get hot. So the best approach is to lean in and become more involved in those moments. We really encourage people to strike while the iron is hot, but not with another hot iron.

TCPR: What do you do when a patient becomes explosive in the room?

Dr. Choi-Kain: The first step is to try to understand what made them feel that their connection to you was threatened. You could say, “Wow, I really upset you. If you can help me understand what I did that upset you, I’d like to know about it.” This teaches the patient that—while it can be completely reasonable to be upset—there are more optimal ways of engaging others when their goal is to keep the other person involved. This is a common problem in BPD. We call it interpersonal hypersensitivity and do a lot of psychoeducation around it.

TCPR: What does interpersonal hypersensitivity look like in real life?

Dr. Choi-Kain: You’ll see it in the cycle of abandonment and impulsive, “frantic” efforts to avoid it. People with BPD struggle to maintain a consistent and positive sense of self. They seek out care and interest from other people as a measure of their worth. The problem is that they become dependent and sensitive to abandonment in those relationships. When threatened by a real or imagined abandonment, they will lash out at others or harm themselves. In the short term, that might actually work to re-engage the other person. Eventually, however, the other person withdraws even more out of fear or frustration. The person with BPD is then alone, and it is in that state of aloneness that they are likely to be impulsive, dissociated, suicidal, and despairing. That’s when hospitalization and other intensive interventions step in, reconstituting the patient for the moment, until the cycle starts again. When we see this cycle as rooted in interpersonal hypersensitivity, it allows us to understand the phenomenology of BPD as an illness that is sometimes misunderstood as manipulative.

TCPR: Many of us miss BPD in male patients. What are some things to look out for in men?

Dr. Choi-Kain: If you go through the diagnostic criteria for BPD, you’re going to see the same thing, whether man or woman. You may see more substance use disorders and inappropriate and intense anger in men. Men also tend to be more difficult to engage in treatment. Women are more likely to have self-harm, affective instability, and identity diffusion (Bayes A and Parker G, Psychiatry Res 2017;257:197–202). These are just generalities; we don’t have very good research on this.

TCPR: How do you plan the frequency of sessions?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Pragmatism can guide that. Often it’s more frequent in the first few years and then tapers off over time, but it may be determined by the practice setting. If the patient is doing poorly, it doesn’t necessarily mean you should see them more often. This is a difficult decision, and you have to consider whether the treatment is helping. It can backfire when you increase an ineffective intervention, pulling the patient into a more exclusive, dependent relationship with the clinician that ultimately disappoints.

TCPR: How do you set boundaries around contacts between visits?

Dr. Choi-Kain: The most useful approach is to describe your availability in terms of your own limitations. If you’re not available after 10 pm, make that about your own inability to be effective at that time of day. Be candid with the patient, describe specific things that they can and can’t call you about, and leave the door open for suicidal emergencies. You can say, “Part of this is that I want to be very consistent, professional, and reliable with you so we can sustain a productive relationship going forward.”

TCPR: Things can get loose with BPD if we don’t have clear roles. Marilyn Monroe’s psychoanalyst had her move into his home, where she helped with laundry and chores.

Dr. Choi-Kain: Those boundary crossings often arise out of good intentions and therapeutic rationales. The problem is that they focus on short-term gains in ways that are not sustainable over the long term, so they ultimately end in disappointments that threaten the treatment. Emotions are intense in this work, and clinicians can be drawn to reassure the patient that they are important or helpful or desirable to be around. Watch out for anything you do that’s outside the norm for your practice, whether it’s longer sessions, reduced fees, or more personal self-disclosure. That’s when you need to seek consultation.

TCPR: What’s a good model for the therapeutic relationship in this work?

Dr. Choi-Kain: To be human yet professional. You are a concerned person who uses their professional skills to advise patients in a frank, candid, and helpful way, and yet maintains some boundaries so you can be predictable.

TCPR: Thanks for your time, Dr. Choi-Kain.

Listen to Podcast Episode: How to Diagnose Borderline Personality Disorder

These 10 questions can identify borderline personality disorder with almost as much precision as a lengthy structured interview.

General Psychiatry Expert Q&ADr. Choi-Kain: We have many effective therapies for BPD. There’s dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), transference-focused therapy, and mentalization-based therapy. Good psychiatric management borrows from the other approaches, but differs in that it developed out of clinical experience rather than a theoretical model, so it’s easier for general psychiatrists to adopt. This approach was actually used as the placebo arm that DBT was compared to, and in some respects it worked as well as DBT. Its effects were comparable in terms of reducing self-harm and suicidality, as well as many of the core symptoms in the diagnostic criteria for BPD (McMain SF et al, Am J Psychiatry 2009;166(12):1365–1374).

TCPR: Walk us through the steps of good psychiatric management.

Dr. Choi-Kain: The approach is very direct and collaborative. We explain the diagnosis and help the patient understand how it plays out in their life. We help them identify goals and plan the treatment around those goals. The goals might include symptom reduction, but we try to focus on functioning and broader life goals, like getting a job or establishing more stable friendships. We want them to develop a life outside of treatment. The message is, “You’re more than a patient. You’re someone who has ambitions outside of just getting better.” These are elements of good psychiatric management for any disorder, from depression to substance use. One thing we’ve learned about the natural course of BPD is that functioning remains fairly impaired for the majority of patients, even when their symptoms improve.

TCPR: Many of the core symptoms of BPD touch on functioning, like unstable relationships and impulsivity, so I’m surprised that functioning doesn’t improve as the symptoms get better.

Dr. Choi-Kain: Well, nobody really knows why that is, but it suggests that focusing on core symptoms of BPD may not be enough to help patients navigate the world better. We have a mantra in this work: “Get a life or get a job.” We want our patients to get a job so they can have a steady place to be, with a regular schedule and well-defined roles. People with BPD need a stable way to be with others. At the end of the day, that’s what they are looking for, and yet they are naturally drawn into intense exclusive relationships where there is no template and no structure. Likewise, there must be clear roles in the treatment so that everything is predicable and has a firm outline to it.

TCPR: And if they can’t find a job?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Any structured social activity could serve the same purpose. College, vocational rehab, church, an exercise group, or a 12-step program. We want them to be part of a community. We don’t want them to develop an exclusive, dependent relationship on the treatment program.

TCPR: What are some typical goals that patients with BPD bring to the table?

Dr. Choi-Kain: They might want to have more independence, or more credibility with others. That would be the long-term goal, and then we’d break it down into short-term, concrete steps. You might say, “I can really understand that you would want your parents to give you the freedom to make your own decisions. What things might you need to do in order to make that happen?” Some of the steps might involve being less reactive, more consistent, and more self-reliant in their day-to-day lives. The art is in translating those goals into specific behavioral changes that are measurable and achievable—for example, “I will develop a monthly budget and spend within my means so I don’t have to borrow money.”

TCPR: Can you do this kind of work when you’re seeing the patient once a month for half an hour?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Absolutely. You can do this with any frequency of meetings. It’s actually more realistic to assess a patient’s progress toward goals over monthly visits because these changes take time to develop.

TCPR: How do you handle this scenario? A patient with BPD moved from another state and is now seeing you for the first time. They are on several medications that they swear by: a stimulant, a benzo, an antipsychotic, a sleep med, and an antidepressant. You suspect some of those might be causing harm.

Dr. Choi-Kain: I’d recommend a collaborative approach that’s based on a rational set of decisions around the medications. First, you’d want to get to know the patient better. Understand their goals and how they see their problems, and tie the treatment to those goals. That takes time, and unless the medications present an imminent danger, you’d want to give them a fair shot at it. If you do change the medications, you’d want that to be a collaborative process. Educate them about the evidence and the risks, and clarify your own limitations around prescriptions in an honest way. You want the patient to feel like the treatment is being done with them, not to them.

TCPR: What are your top dos and don’ts for communicating with patients with BPD?

Dr. Choi-Kain: The top dos are to be honest and direct. The natural tendency is to be too careful about what’s said and “walk on eggshells” because people with BPD are very sensitive. That doesn’t work well, because they also happen to be sensitive to body language, so they can pick up on disingenuousness. Well-meaning people often try to cover up their own negativity by being overly nice, but that ultimately harms the patient’s ability to trust them. In good psychiatric management, we respect the patient and believe they can manage what we have to say. If they get upset about it, we try to understand their reaction.

TCPR: I’ve heard that patients with BPD misread facial expressions. How does that play out in treatment?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Yes, they have particular difficulty with neutral faces. They don’t do well with ambiguity. So the traditional “blank slate” is not going to work here. They also tend to be better at reading negative faces than others and are more sensitive to negative expressions (Mitchell AE et al, Neuropsychol Rev 2014;24:166–184). People with BPD need to know where you stand, so we avoid vague expressions. Whether it’s verbal or nonverbal, we try to communicate openly and clearly.

TCPR: Some people advise to “strike while the iron is cold” when confronting difficult subjects with patients who have BPD.

Dr. Choi-Kain: I’d phrase that differently. Patients with BPD want to know what is on your mind, whether the temperature is hot or cold. They may want to know more when the temperature is hot. That’s because heated emotions often rise up when the patient feels that their connection to you has been threatened. We teach patients that their BPD symptoms tend to fluctuate with the level of engagement they have with significant others. When they feel connected and secure in their relationship, they tend to be very collaborative. But they are also sensitive to signs of rejection or disapproval. When their connection feels threatened, the emotions get hot. So the best approach is to lean in and become more involved in those moments. We really encourage people to strike while the iron is hot, but not with another hot iron.

TCPR: What do you do when a patient becomes explosive in the room?

Dr. Choi-Kain: The first step is to try to understand what made them feel that their connection to you was threatened. You could say, “Wow, I really upset you. If you can help me understand what I did that upset you, I’d like to know about it.” This teaches the patient that—while it can be completely reasonable to be upset—there are more optimal ways of engaging others when their goal is to keep the other person involved. This is a common problem in BPD. We call it interpersonal hypersensitivity and do a lot of psychoeducation around it.

TCPR: What does interpersonal hypersensitivity look like in real life?

Dr. Choi-Kain: You’ll see it in the cycle of abandonment and impulsive, “frantic” efforts to avoid it. People with BPD struggle to maintain a consistent and positive sense of self. They seek out care and interest from other people as a measure of their worth. The problem is that they become dependent and sensitive to abandonment in those relationships. When threatened by a real or imagined abandonment, they will lash out at others or harm themselves. In the short term, that might actually work to re-engage the other person. Eventually, however, the other person withdraws even more out of fear or frustration. The person with BPD is then alone, and it is in that state of aloneness that they are likely to be impulsive, dissociated, suicidal, and despairing. That’s when hospitalization and other intensive interventions step in, reconstituting the patient for the moment, until the cycle starts again. When we see this cycle as rooted in interpersonal hypersensitivity, it allows us to understand the phenomenology of BPD as an illness that is sometimes misunderstood as manipulative.

TCPR: Many of us miss BPD in male patients. What are some things to look out for in men?

Dr. Choi-Kain: If you go through the diagnostic criteria for BPD, you’re going to see the same thing, whether man or woman. You may see more substance use disorders and inappropriate and intense anger in men. Men also tend to be more difficult to engage in treatment. Women are more likely to have self-harm, affective instability, and identity diffusion (Bayes A and Parker G, Psychiatry Res 2017;257:197–202). These are just generalities; we don’t have very good research on this.

TCPR: How do you plan the frequency of sessions?

Dr. Choi-Kain: Pragmatism can guide that. Often it’s more frequent in the first few years and then tapers off over time, but it may be determined by the practice setting. If the patient is doing poorly, it doesn’t necessarily mean you should see them more often. This is a difficult decision, and you have to consider whether the treatment is helping. It can backfire when you increase an ineffective intervention, pulling the patient into a more exclusive, dependent relationship with the clinician that ultimately disappoints.

TCPR: How do you set boundaries around contacts between visits?

Dr. Choi-Kain: The most useful approach is to describe your availability in terms of your own limitations. If you’re not available after 10 pm, make that about your own inability to be effective at that time of day. Be candid with the patient, describe specific things that they can and can’t call you about, and leave the door open for suicidal emergencies. You can say, “Part of this is that I want to be very consistent, professional, and reliable with you so we can sustain a productive relationship going forward.”

TCPR: Things can get loose with BPD if we don’t have clear roles. Marilyn Monroe’s psychoanalyst had her move into his home, where she helped with laundry and chores.

Dr. Choi-Kain: Those boundary crossings often arise out of good intentions and therapeutic rationales. The problem is that they focus on short-term gains in ways that are not sustainable over the long term, so they ultimately end in disappointments that threaten the treatment. Emotions are intense in this work, and clinicians can be drawn to reassure the patient that they are important or helpful or desirable to be around. Watch out for anything you do that’s outside the norm for your practice, whether it’s longer sessions, reduced fees, or more personal self-disclosure. That’s when you need to seek consultation.

TCPR: What’s a good model for the therapeutic relationship in this work?

Dr. Choi-Kain: To be human yet professional. You are a concerned person who uses their professional skills to advise patients in a frank, candid, and helpful way, and yet maintains some boundaries so you can be predictable.

TCPR: Thanks for your time, Dr. Choi-Kain.

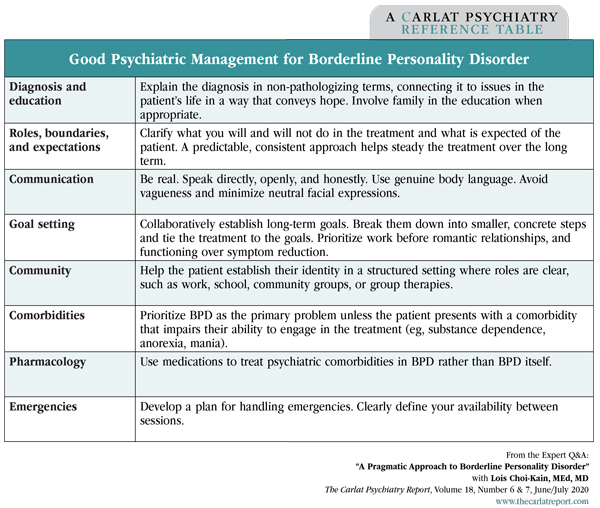

Table: Good Psychiatric Management for Borderline Personality Disorder

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

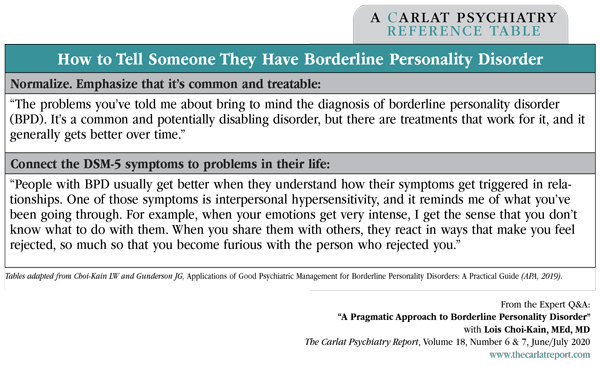

Table: How to Tell Someone They Have Borderline Personality Disorder

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Listen to Podcast Episode: How to Diagnose Borderline Personality Disorder

These 10 questions can identify borderline personality disorder with almost as much precision as a lengthy structured interview.

KEYWORDS borderline-personality-disorder bpd brief-psychotherapy psychotherapy therapy-during-medication-appointment therapy-with-med-management

Issue Date: June 10, 2020

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)