Home » Welcome to the 21st Century Cures Act Information Sharing Rules

Welcome to the 21st Century Cures Act Information Sharing Rules

May 20, 2021

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Jess Levy, MD.

Child and adolescent psychiatrist, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, OH.

Dr. Levy has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

The 21st Century Cures Act (or the “Cures Act” for short) was a federal law passed in 2016 that included various mental health provisions (www.healthit.gov/curesrule). One of them is a law prohibiting what’s now called “information blocking.” In short, information blocking means preventing your patient from accessing information in their medical record. As of April 5, 2021, the law stipulates that patients must be able to access nearly all of the information we have in their electronic chart, on demand. This article focuses on how the Cures Act applies to child psychiatrists, how it impacts what we record in charts, what happens to that information, and how to best work with patients and families as they gain more access to their information.

Impact of information blocking

As of April 5, 2021, all clinicians are expected to respond to patient requests to view clinical data such as treatment notes, laboratory results, and medical problems without delay. For most of us, this means 1–2 business days after receiving a request. Intentional or unnecessary delays in fulfilling patient requests are also considered information blocking. An example of this kind of delay is requiring a patient or family member to sign a document, often erroneously referred to as a “HIPAA form,” before transmitting their health records to another provider. This has been common practice, but now it might be considered information blocking unless certain exceptions can be demonstrated. Charging a fee for electronic access to records can also be information blocking.

What do you have to share with patients? Just about everything in your chart—including clinical notes, medication lists, vital signs, lab results, and assessments and treatment plans.

Exceptions to the rule

Worried about releasing sensitive information? You can restrict requests for data only when doing so is reasonable and necessary, and addresses a significant risk (www.tinyurl.com/4ssfee8h).

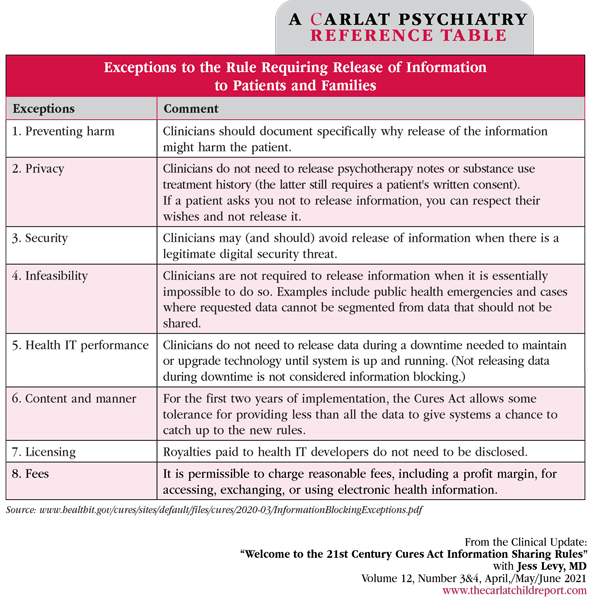

While the definition of “significant risk” is not clear, we need to clearly document our reasons for restricting access and fulfill as much of the request as we can. And keep in mind that this law pertains to requests for information; there is no requirement that we proactively share health data with patients or guardians who have not requested access to the information. There are eight recognized exceptions where it might be permissible to not honor a patient’s request to view their information, two of which pertain directly to our work. See table below.

What about teens?

Can teens see their records? The short answer is yes. Can parents and other guardians see them? That depends on whether the teen grants them access as proxies, but also on state laws about the limits of adolescent confidentiality. Some teens do not want their parents actively involved in their treatment. You should review your state’s laws about what data can be shared with parents, and when consent is needed.

Many EHRs have a multitiered access system where less sensitive clinical data are available to parents, while other data such as clinical notes and certain laboratory results are available only to the teen. A teen can choose to go onto the EHR portal and add their parent or guardian as a proxy if they wish for that parent or guardian to have electronic access to notes or more sensitive data.

Help your teen patient think through the risks and benefits when deciding whether to allow other people to access their records, and at what level (ie, medical vs therapy notes). Remind teens not to share their password with anyone. Help them understand the long-term risks of sharing their data such as cybersecurity risks and possible ramifications if future employers see the data (Pageler NM et al, Pediatrics 2021;147(3):e2020034199).

Planning for the age of open notes

Your notes will be open to patients, families, and colleagues alike. Here are some guidelines for writing notes in this new age:

If your patient or family encounters data that they find inaccurate or troubling, listen to their concerns. Have a procedure to correct errors brought to your attention. Consult a lawyer or your malpractice provider if there is evidence of harm to a patient after viewing data in the chart.

Remember that open notes also provide new opportunities for patient engagement. For instance, when written in plain language, your notes can double as patient instructions. I often start follow-up visits by reading out loud the salient points from the patient’s last progress note. I find this to be a great way to frame our conversation at follow-up time and remind patients why we chose to proceed as we did.

CCPR Verdict: Like it or not, the new norm will soon be for patients to have on-demand access to their electronic charts. Although these reforms affect all specialties, we in child psychiatry face unique challenges in opening our notes to patients and their families. We can adapt by being thoughtful, respectful, and proactive in our documentation.

Child PsychiatryImpact of information blocking

As of April 5, 2021, all clinicians are expected to respond to patient requests to view clinical data such as treatment notes, laboratory results, and medical problems without delay. For most of us, this means 1–2 business days after receiving a request. Intentional or unnecessary delays in fulfilling patient requests are also considered information blocking. An example of this kind of delay is requiring a patient or family member to sign a document, often erroneously referred to as a “HIPAA form,” before transmitting their health records to another provider. This has been common practice, but now it might be considered information blocking unless certain exceptions can be demonstrated. Charging a fee for electronic access to records can also be information blocking.

What do you have to share with patients? Just about everything in your chart—including clinical notes, medication lists, vital signs, lab results, and assessments and treatment plans.

Exceptions to the rule

Worried about releasing sensitive information? You can restrict requests for data only when doing so is reasonable and necessary, and addresses a significant risk (www.tinyurl.com/4ssfee8h).

While the definition of “significant risk” is not clear, we need to clearly document our reasons for restricting access and fulfill as much of the request as we can. And keep in mind that this law pertains to requests for information; there is no requirement that we proactively share health data with patients or guardians who have not requested access to the information. There are eight recognized exceptions where it might be permissible to not honor a patient’s request to view their information, two of which pertain directly to our work. See table below.

What about teens?

Can teens see their records? The short answer is yes. Can parents and other guardians see them? That depends on whether the teen grants them access as proxies, but also on state laws about the limits of adolescent confidentiality. Some teens do not want their parents actively involved in their treatment. You should review your state’s laws about what data can be shared with parents, and when consent is needed.

Many EHRs have a multitiered access system where less sensitive clinical data are available to parents, while other data such as clinical notes and certain laboratory results are available only to the teen. A teen can choose to go onto the EHR portal and add their parent or guardian as a proxy if they wish for that parent or guardian to have electronic access to notes or more sensitive data.

Help your teen patient think through the risks and benefits when deciding whether to allow other people to access their records, and at what level (ie, medical vs therapy notes). Remind teens not to share their password with anyone. Help them understand the long-term risks of sharing their data such as cybersecurity risks and possible ramifications if future employers see the data (Pageler NM et al, Pediatrics 2021;147(3):e2020034199).

Planning for the age of open notes

Your notes will be open to patients, families, and colleagues alike. Here are some guidelines for writing notes in this new age:

- Assume that everything you write in the EHR will be viewed by the patient. This includes comments and messages to other doctors that are transmitted through the EHR.

- Be polite and respectful in notes and in correspondence to colleagues.

- Make sure your notes are written in a neutral perspective. Where possible, use patient quotes rather than making an assumption about a patient’s motivations. For example, if a patient reports multiple symptoms of depression since a breakup, consider noting this in the patient’s own words: “I’m so depressed. I can’t sleep or eat.” vs generalizing: “Patient is severely depressed due to the breakup.”

- Maintain cultural sensitivity. Avoid broad statements that deride an individual for engaging in a culturally sanctioned practice. For example, rather than writing “The child is up all night and tired during the day because the mother has the children all in the family bed.” consider “The mother reports the child is waking 2–3 times per night and waking others in the family bed, which she notes is an uncommon problem among her cultural community.”

- Protect the privacy of LGBTQIA+ youth who may use names or pronouns that parents disagree with. Privately discuss names or pronouns to use in your notes ahead of time in case the patient is concerned about a parent seeing them. If you are unsure, consider gender-neutral pronouns such as “they” instead of “he” or “she.”

- Take care when documenting unflattering things about patients. Say we document our thought that a patient does not seem to have the ability to complete an educational program that is deeply important to their future plans. Upon reading this “conclusion,” our patient may feel despondent, lose sleep, have trouble concentrating, or perhaps experience suicidal thinking. If you suspect a patient will be harmed or put at risk based on something you write, be proactive and document why you believe your patient will be harmed by accessing the data.

- Make sure your pager or cell number is not listed in your progress notes unless you want patients to have it.

If your patient or family encounters data that they find inaccurate or troubling, listen to their concerns. Have a procedure to correct errors brought to your attention. Consult a lawyer or your malpractice provider if there is evidence of harm to a patient after viewing data in the chart.

Remember that open notes also provide new opportunities for patient engagement. For instance, when written in plain language, your notes can double as patient instructions. I often start follow-up visits by reading out loud the salient points from the patient’s last progress note. I find this to be a great way to frame our conversation at follow-up time and remind patients why we chose to proceed as we did.

CCPR Verdict: Like it or not, the new norm will soon be for patients to have on-demand access to their electronic charts. Although these reforms affect all specialties, we in child psychiatry face unique challenges in opening our notes to patients and their families. We can adapt by being thoughtful, respectful, and proactive in our documentation.

Table: Exceptions to the Rule Requiring Release of Information to Patients and Families

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Issue Date: May 20, 2021

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)