Home » Disulfiram: An Underused Strategy for Alcohol Use Disorders

Disulfiram: An Underused Strategy for Alcohol Use Disorders

June 29, 2021

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Stephen Wyatt, DO.

Private practice psychiatrist with certification in addiction psychiatry, Charlotte, NC.

Dr. Wyatt has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Alcohol ranks third among preventable causes of death in the US, but it is by far the most undertreated. Fewer than 8% of people with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) receive treatment for their disease, and only a minority of them receive FDA-approved medications. Those medications are acamprosate (Campral), naltrexone (Vivitrol, ReVia), and disulfiram (Antabuse). Disulfiram is the oldest of the bunch, and it has accumulated a few myths over its 70-year career that have hindered its use.

How it works

Disulfiram’s mechanism is primarily pharmacokinetic. It irreversibly blocks the enzyme that clears out acetaldehyde, a metabolite of alcohol that is responsible for the nausea, vomiting, and headaches known colloquially as a hangover. The result is that patients who drink while on disulfiram, even in small amounts, will suffer a severe hangover within 5–15 minutes. Depending on the dose of disulfiram and how much alcohol is ingested, this interaction may result in chest pain, weakness, difficulty breathing, and rarely death (Kristenson H, Alcohol Alcohol 1995;30(6):775–783).

Besides this metabolic effect, disulfiram also inhibits the metabolism of dopamine in the CNS. This dopaminergic effect does not seem to influence alcohol use, but it does reduce the rewarding effects of cocaine. Thus disulfiram is effective against both addictions in the often co-occurring alcohol and cocaine use disorders (Carroll KM et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61(3):264–272).

The disulfiram effect was discovered in 1937 when workers exposed to this compound in the manufacturing of tires (where it was used to stiffen rubber) became ill after drinking alcohol. Clinical trials in AUDs ensued, leading to its FDA approval in 1951. Our understanding of disulfiram has evolved since then, but an early mishap—where doctors advised patients to drink on disulfiram—led to a lingering perception that the drug is too dangerous to use in practice.

Myth #1: Safety

At first, disulfiram was thought to work through aversive conditioning, and some physicians advised patients to drink on it in order to experience the aversive reaction. Rarely, the reaction can be fatal, so this practice was soon abandoned. Disulfiram’s safety was further improved by lowering the daily dose from 1,000–3,000 mg to 250 mg. With these precautions, mortality from the disulfiram alcohol reaction has not been reported in many years (Chick J, Drug Saf 1999;20(5):427–435).

Outside of the alcohol interaction, the most common side effects on disulfiram are a maculopapular rash, bad breath, and fatigue. Disulfiram does have a few contraindications: cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (the drug can raise blood pressure and there are rare reports of heart failure on it), significant hepatic impairment (disulfiram can be hepatotoxic), psychosis (which can worsen on disulfiram), and pregnancy (disulfiram is a teratogen). It should also be avoided in patients who are cognitively impaired because of the need to understand and follow the instructions. Initial liver enzymes (LFTs) should be obtained and monitored every 6 months during treatment, although most cases of elevated LFTs on disulfiram are due to alcohol itself (Iber FL et al, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1987;11(3):301–304).

All this is not to suggest that disulfiram is as safe as, say, buspirone. However, its risks are many leagues lower than those of the disease it treats, and that’s the kind of reasoning that should guide its use. But is it really effective for AUDs?

Myth #2: Efficacy

Disulfiram’s efficacy is often doubted. The thinking is that a patient with mild AUD will stay on it (and may not need it), while a patient with significant AUD will simply stop the medication when they have the urge to drink. In fact, disulfiram’s half-life is 2–5 days, and its alcohol interaction continues for up to 2 weeks after it is stopped, ensuring that there is some time for patients to reconsider their decision to relapse.

There is a grain of truth in the lack of efficacy myth, however. Disulfiram is much more effective when given under supervision, either by a friend, relative, or clinical staff. In one meta-analysis, unsupervised disulfiram worked no better than control, while supervised disulfiram had a large effect size (0.8) compared to a similarly supervised non-disulfiram control group (Skinner MD et al, PLoS One 2014;9(2):e87366).

In practice, unsupervised disulfiram can work in highly motivated patients, such as professionals whose careers would be derailed by a relapse. But supervised delivery is the ideal. Clinically supervised treatment is available at some centers, and private practitioners can ask the patient to enlist a trusted friend or relative to ensure they remain adherent.

Disulfiram’s efficacy is also questioned because it did not work when tested against a placebo, but that is an inevitable result of its mechanism. To ensure adequate blinding, subjects on placebo are issued the same stern warning about dangerous reactions with alcohol, and this leads them to cut back as much as the disulfiram group. It is also easy to break the blind by ingesting a small amount of alcohol. So how do we know that it works? The main support comes from unblinded randomized trials that have compared disulfiram to psychotherapy, naltrexone, or acamprosate.

There are at least 17 of those trials, and in the majority of them disulfiram performed much better than the active comparator. For example, it surpassed acamprosate and naltrexone with a magnitude similar to the difference between stimulant and placebo in ADHD—ie, effect size of 0.8 (Skinner et al, 2014). These effect sizes are somewhat inflated, however, by the fact that disulfiram requires total abstinence, while other treatments succeed by merely reducing the use of alcohol.

The ideal patient

The ideal candidate for disulfiram is a patient who has been unsuccessful in reducing alcohol and has experienced disastrous effects with its use. These are patients who resonate with the adage “one is too many, and a thousand is not enough.” They understand the need for total abstinence and recognize they need external help in achieving it. They have a caring person in their life who can watch them take the medication, and they are hopefully involved in a 12-step program or psychotherapy for addiction. It’s with these patients that I’ll open up a discussion of disulfiram. After explaining how the drug works, I will tell the patient that it is most effective when taken in front of another person. This can also solidify mutual trust in that relationship.

Long-term therapy is the ideal for prevention, but some patients are successful taking disulfiram episodically. Patients with significant self-awareness and commitment to sobriety may benefit from taking disulfiram when, for example, they are faced with an event where alcohol will be freely flowing, presenting a significant risk of relapse.

All patients struggle with adherence, and this problem is compounded by addiction. For a person with AUD, cravings feel like a basic need. On the other hand, some healing takes place in these habitual pathways after patients have been sober for a couple of months. Cravings lessen and confidence improves. Their brain is recovering, and good things are starting to happen in their life, which is harder to let go of.

TCPR Verdict: Disulfiram is very effective in AUDs, particularly when its delivery is supervised by a friend, relative, or clinical staff. Low doses are safer and work just as well as higher ones. As long as the patient does not have a contraindication, disulfiram is a relatively safe intervention for a disease that can be fatal when left untreated.

To learn more, listen to our 6/28/21 podcast, “The Rediscovery of Antabuse.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

To learn more, listen to our 6/28/21 podcast, “The Rediscovery of Antabuse.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

General PsychiatryHow it works

Disulfiram’s mechanism is primarily pharmacokinetic. It irreversibly blocks the enzyme that clears out acetaldehyde, a metabolite of alcohol that is responsible for the nausea, vomiting, and headaches known colloquially as a hangover. The result is that patients who drink while on disulfiram, even in small amounts, will suffer a severe hangover within 5–15 minutes. Depending on the dose of disulfiram and how much alcohol is ingested, this interaction may result in chest pain, weakness, difficulty breathing, and rarely death (Kristenson H, Alcohol Alcohol 1995;30(6):775–783).

Besides this metabolic effect, disulfiram also inhibits the metabolism of dopamine in the CNS. This dopaminergic effect does not seem to influence alcohol use, but it does reduce the rewarding effects of cocaine. Thus disulfiram is effective against both addictions in the often co-occurring alcohol and cocaine use disorders (Carroll KM et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61(3):264–272).

The disulfiram effect was discovered in 1937 when workers exposed to this compound in the manufacturing of tires (where it was used to stiffen rubber) became ill after drinking alcohol. Clinical trials in AUDs ensued, leading to its FDA approval in 1951. Our understanding of disulfiram has evolved since then, but an early mishap—where doctors advised patients to drink on disulfiram—led to a lingering perception that the drug is too dangerous to use in practice.

Myth #1: Safety

At first, disulfiram was thought to work through aversive conditioning, and some physicians advised patients to drink on it in order to experience the aversive reaction. Rarely, the reaction can be fatal, so this practice was soon abandoned. Disulfiram’s safety was further improved by lowering the daily dose from 1,000–3,000 mg to 250 mg. With these precautions, mortality from the disulfiram alcohol reaction has not been reported in many years (Chick J, Drug Saf 1999;20(5):427–435).

Outside of the alcohol interaction, the most common side effects on disulfiram are a maculopapular rash, bad breath, and fatigue. Disulfiram does have a few contraindications: cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (the drug can raise blood pressure and there are rare reports of heart failure on it), significant hepatic impairment (disulfiram can be hepatotoxic), psychosis (which can worsen on disulfiram), and pregnancy (disulfiram is a teratogen). It should also be avoided in patients who are cognitively impaired because of the need to understand and follow the instructions. Initial liver enzymes (LFTs) should be obtained and monitored every 6 months during treatment, although most cases of elevated LFTs on disulfiram are due to alcohol itself (Iber FL et al, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1987;11(3):301–304).

All this is not to suggest that disulfiram is as safe as, say, buspirone. However, its risks are many leagues lower than those of the disease it treats, and that’s the kind of reasoning that should guide its use. But is it really effective for AUDs?

Myth #2: Efficacy

Disulfiram’s efficacy is often doubted. The thinking is that a patient with mild AUD will stay on it (and may not need it), while a patient with significant AUD will simply stop the medication when they have the urge to drink. In fact, disulfiram’s half-life is 2–5 days, and its alcohol interaction continues for up to 2 weeks after it is stopped, ensuring that there is some time for patients to reconsider their decision to relapse.

There is a grain of truth in the lack of efficacy myth, however. Disulfiram is much more effective when given under supervision, either by a friend, relative, or clinical staff. In one meta-analysis, unsupervised disulfiram worked no better than control, while supervised disulfiram had a large effect size (0.8) compared to a similarly supervised non-disulfiram control group (Skinner MD et al, PLoS One 2014;9(2):e87366).

In practice, unsupervised disulfiram can work in highly motivated patients, such as professionals whose careers would be derailed by a relapse. But supervised delivery is the ideal. Clinically supervised treatment is available at some centers, and private practitioners can ask the patient to enlist a trusted friend or relative to ensure they remain adherent.

Disulfiram’s efficacy is also questioned because it did not work when tested against a placebo, but that is an inevitable result of its mechanism. To ensure adequate blinding, subjects on placebo are issued the same stern warning about dangerous reactions with alcohol, and this leads them to cut back as much as the disulfiram group. It is also easy to break the blind by ingesting a small amount of alcohol. So how do we know that it works? The main support comes from unblinded randomized trials that have compared disulfiram to psychotherapy, naltrexone, or acamprosate.

There are at least 17 of those trials, and in the majority of them disulfiram performed much better than the active comparator. For example, it surpassed acamprosate and naltrexone with a magnitude similar to the difference between stimulant and placebo in ADHD—ie, effect size of 0.8 (Skinner et al, 2014). These effect sizes are somewhat inflated, however, by the fact that disulfiram requires total abstinence, while other treatments succeed by merely reducing the use of alcohol.

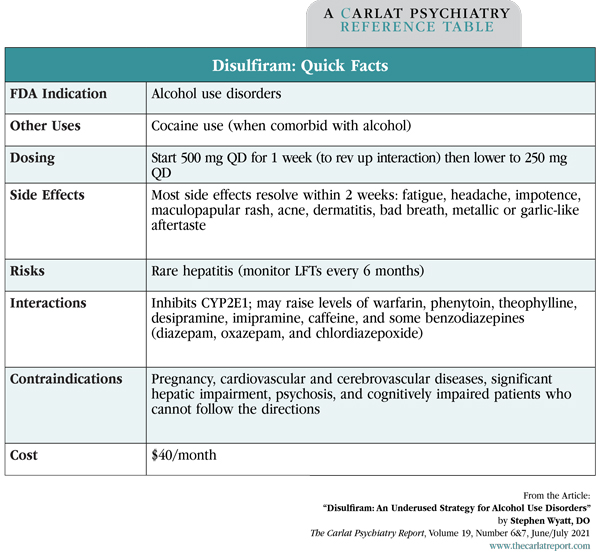

Table: Disulfiram: Quick Facts

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

The ideal patient

The ideal candidate for disulfiram is a patient who has been unsuccessful in reducing alcohol and has experienced disastrous effects with its use. These are patients who resonate with the adage “one is too many, and a thousand is not enough.” They understand the need for total abstinence and recognize they need external help in achieving it. They have a caring person in their life who can watch them take the medication, and they are hopefully involved in a 12-step program or psychotherapy for addiction. It’s with these patients that I’ll open up a discussion of disulfiram. After explaining how the drug works, I will tell the patient that it is most effective when taken in front of another person. This can also solidify mutual trust in that relationship.

Long-term therapy is the ideal for prevention, but some patients are successful taking disulfiram episodically. Patients with significant self-awareness and commitment to sobriety may benefit from taking disulfiram when, for example, they are faced with an event where alcohol will be freely flowing, presenting a significant risk of relapse.

All patients struggle with adherence, and this problem is compounded by addiction. For a person with AUD, cravings feel like a basic need. On the other hand, some healing takes place in these habitual pathways after patients have been sober for a couple of months. Cravings lessen and confidence improves. Their brain is recovering, and good things are starting to happen in their life, which is harder to let go of.

TCPR Verdict: Disulfiram is very effective in AUDs, particularly when its delivery is supervised by a friend, relative, or clinical staff. Low doses are safer and work just as well as higher ones. As long as the patient does not have a contraindication, disulfiram is a relatively safe intervention for a disease that can be fatal when left untreated.

KEYWORDS abstinence addiction addiction-treatment alcohol alcohol-use alcohol-use-disorder alcoholism disulfiram free_articles psychopharm-myths

Issue Date: June 29, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)