Home » Inhalants: An Invisible Danger

Inhalants: An Invisible Danger

September 10, 2021

From The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report

Michael Weaver, MD, FASAM,

Professor and medical director at the Center for Neurobehavioral Research on Addictions at the University of Texas Medical School.

Dr. Weaver has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity

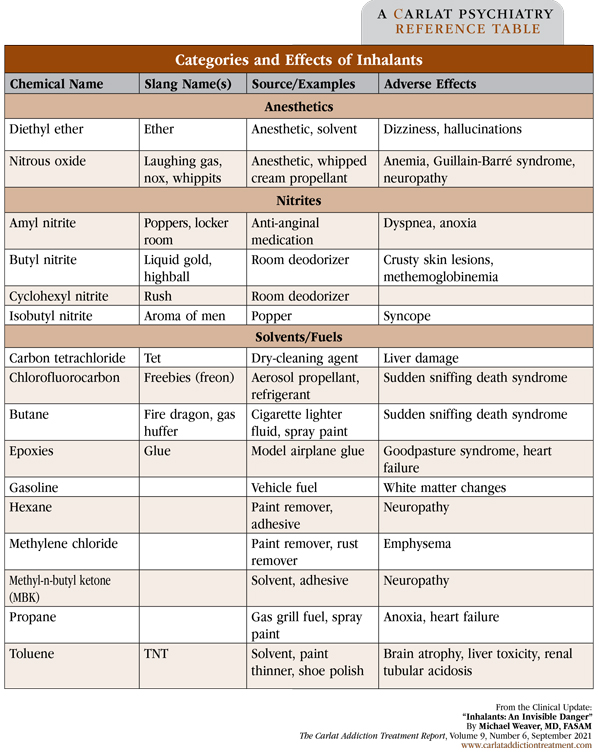

Inhalants are a diverse group of chemical compounds that are inhaled to obtain a brief high that is a little like an alcohol buzz. Many common household items can be used as inhalants. They include air dusters, epoxies such as model airplane glue, and a variety of hydrocarbons such as butane lighter fluid, gasoline, paint thinner, and other cleaning solvents (Weaver MF. Hallucinogens and Other Drugs. In Addiction Treatment. Newburyport, MA: Carlat Publishing; 2017). Even medical gases can be used recreationally, including nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”), ether, and amyl nitrite (an anti-anginal vasodilator). See the table below for categories, names, and effects of some of the more common inhalants.

While many addictive drugs such as opioids or alcohol are used on a daily basis, inhalants are more commonly used sporadically and in specific social situations, such as at a party or rave. Inhalants are popular with younger people because they are easy to obtain and produce a brief high. In addition, there are very few legal penalties for possessing inhalants since they typically have other legal uses, in contrast to other illegal drugs. Certain inhalants, especially nitrites, are popular among men who have sex with men (MSM) as enhancements to sexual activity. When used infrequently and in moderation, inhalants rarely cause problems, and because they don’t produce prominent physical dependence, you will be unlikely to see people who are exclusively addicted to specific inhalants. However, some people use these drugs frequently, mixing and matching them with a variety of other drugs.

How are inhalants used?

There are several methods of recreational use for these chemicals. “Huffing” or “bagging” involves inhaling fumes from a solvent-soaked rag, often inside a plastic or paper bag. Some inhalants, especially nitrites, are commercially available at head shops (stores specializing in the sale of drug paraphernalia) or gas station convenience stores packaged in plastic containers called “poppers.” Some people inhale aerosol propellants for paint, hair spray, whipped cream, and other products directly from the spray can. Regardless of the method of use, all of these compounds have a very short duration of action, which tends to encourage frequent redosing.

Dangers of inhalant use

Because many inhalants are industrial solvents and other compounds not intended for human consumption, they can be quite dangerous. When directly inhaled, inhalant gas will replace lung volume normally occupied by air, potentially leading to hypoxia and end-organ hypoxic injury.

In addition to hypoxic effects, inhalants can have direct toxicity on many organ systems. Those who huff chronically are vulnerable to liver damage, kidney failure, peripheral neuropathy, and early dementia. Arrhythmias and neurotoxicity are particularly problematic and can eventually lead to death.

A particular concern is “sudden sniffing death syndrome,” a rare but alarming condition in which a young and otherwise healthy person can die from a single heavy inhalant exposure. Most common with chlorofluorocarbon-based propellants and refrigerants, rapid death results from sensitization of myocardial cells to catecholamines, causing sudden arrythmias, including fatal ones such as ventricular fibrillation (Shepherd RT, Hum Toxicol 1989;8(4):287–291).

Heavy use in an area that is not well ventilated can cause hypoxia as well as significant “secondhand” inhalant exposure. Many inhalants are highly flammable and can easily lead to injury from burns.

How to recognize inhalant use

Due to their typically sporadic use and brief high, inhalant intoxication is rare in the outpatient setting. It may occasionally be seen in the emergency department, especially in the context of other injuries related to huffing. But there are some signs and symptoms to watch for that may indicate your patient is using inhalants.

Some of the most obvious physical signs of inhalant misuse are dermatological. Hyperpigmentation from chronic inflammation, sores, and crusty lesions around the nose and mouth (called “glue sniffer’s eczema”) may be seen. Rhinorrhea, nose bleeds, pharyngeal erythema, and anosmia can result from direct contact with chemicals. Liver damage can cause an enlarged liver and scleral icterus. Neurological toxicity can result in nystagmus, peripheral neuropathy, and short-term memory loss. On labs, you might see anemia, elevated creatinine, elevated liver transaminases, or the presence of methemoglobin.

Addressing inhalant use

When asking about inhalants, I’ll use the typical normalization method: “Many people have tried things like whippits or poppers (nitrous oxide or nitrites). Have you tried them or anything like them?” If the patient says no, I’ll give other examples of “stuff you huff,” like spray paint or gasoline fumes. Another important question is the frequency of use: Is it regular or just experimental? Opportunistic (sporadic) users will often mature out of the use of these drugs, but up to 20% of those who try inhalants will go on to develop a use disorder (Nguyen J et al, Int J Drug Policy 2016;31:15–24).

In more frequent users, I look for untreated depression and maladaptive coping skills. For MSM, it is worthwhile to ask about risk factors for sexually transmitted infections. For some, inhalants can act as a “gateway” drug, so always ask about use of other substances as well.

Treatment for inhalant use is behaviorally focused, primarily CBT, as there is no pharmacotherapy available for inhalant use disorder. Adolescent-focused intensive outpatient addiction treatment programs can be helpful, though they can be difficult to find. General outpatient treatment is generally easier to access. Therapy tends to focus on teaching adaptive ways of dealing with stressors rather than turning to substance use.

CATR Verdict: Inhalant use is often overlooked and underdiagnosed but can have serious consequences. Looking for telltale signs, especially in adolescents and MSM, can help you intervene early and offer behavioral-based treatment.

Addiction TreatmentWhile many addictive drugs such as opioids or alcohol are used on a daily basis, inhalants are more commonly used sporadically and in specific social situations, such as at a party or rave. Inhalants are popular with younger people because they are easy to obtain and produce a brief high. In addition, there are very few legal penalties for possessing inhalants since they typically have other legal uses, in contrast to other illegal drugs. Certain inhalants, especially nitrites, are popular among men who have sex with men (MSM) as enhancements to sexual activity. When used infrequently and in moderation, inhalants rarely cause problems, and because they don’t produce prominent physical dependence, you will be unlikely to see people who are exclusively addicted to specific inhalants. However, some people use these drugs frequently, mixing and matching them with a variety of other drugs.

How are inhalants used?

There are several methods of recreational use for these chemicals. “Huffing” or “bagging” involves inhaling fumes from a solvent-soaked rag, often inside a plastic or paper bag. Some inhalants, especially nitrites, are commercially available at head shops (stores specializing in the sale of drug paraphernalia) or gas station convenience stores packaged in plastic containers called “poppers.” Some people inhale aerosol propellants for paint, hair spray, whipped cream, and other products directly from the spray can. Regardless of the method of use, all of these compounds have a very short duration of action, which tends to encourage frequent redosing.

Dangers of inhalant use

Because many inhalants are industrial solvents and other compounds not intended for human consumption, they can be quite dangerous. When directly inhaled, inhalant gas will replace lung volume normally occupied by air, potentially leading to hypoxia and end-organ hypoxic injury.

In addition to hypoxic effects, inhalants can have direct toxicity on many organ systems. Those who huff chronically are vulnerable to liver damage, kidney failure, peripheral neuropathy, and early dementia. Arrhythmias and neurotoxicity are particularly problematic and can eventually lead to death.

A particular concern is “sudden sniffing death syndrome,” a rare but alarming condition in which a young and otherwise healthy person can die from a single heavy inhalant exposure. Most common with chlorofluorocarbon-based propellants and refrigerants, rapid death results from sensitization of myocardial cells to catecholamines, causing sudden arrythmias, including fatal ones such as ventricular fibrillation (Shepherd RT, Hum Toxicol 1989;8(4):287–291).

Heavy use in an area that is not well ventilated can cause hypoxia as well as significant “secondhand” inhalant exposure. Many inhalants are highly flammable and can easily lead to injury from burns.

How to recognize inhalant use

Due to their typically sporadic use and brief high, inhalant intoxication is rare in the outpatient setting. It may occasionally be seen in the emergency department, especially in the context of other injuries related to huffing. But there are some signs and symptoms to watch for that may indicate your patient is using inhalants.

Some of the most obvious physical signs of inhalant misuse are dermatological. Hyperpigmentation from chronic inflammation, sores, and crusty lesions around the nose and mouth (called “glue sniffer’s eczema”) may be seen. Rhinorrhea, nose bleeds, pharyngeal erythema, and anosmia can result from direct contact with chemicals. Liver damage can cause an enlarged liver and scleral icterus. Neurological toxicity can result in nystagmus, peripheral neuropathy, and short-term memory loss. On labs, you might see anemia, elevated creatinine, elevated liver transaminases, or the presence of methemoglobin.

Addressing inhalant use

When asking about inhalants, I’ll use the typical normalization method: “Many people have tried things like whippits or poppers (nitrous oxide or nitrites). Have you tried them or anything like them?” If the patient says no, I’ll give other examples of “stuff you huff,” like spray paint or gasoline fumes. Another important question is the frequency of use: Is it regular or just experimental? Opportunistic (sporadic) users will often mature out of the use of these drugs, but up to 20% of those who try inhalants will go on to develop a use disorder (Nguyen J et al, Int J Drug Policy 2016;31:15–24).

In more frequent users, I look for untreated depression and maladaptive coping skills. For MSM, it is worthwhile to ask about risk factors for sexually transmitted infections. For some, inhalants can act as a “gateway” drug, so always ask about use of other substances as well.

Treatment for inhalant use is behaviorally focused, primarily CBT, as there is no pharmacotherapy available for inhalant use disorder. Adolescent-focused intensive outpatient addiction treatment programs can be helpful, though they can be difficult to find. General outpatient treatment is generally easier to access. Therapy tends to focus on teaching adaptive ways of dealing with stressors rather than turning to substance use.

CATR Verdict: Inhalant use is often overlooked and underdiagnosed but can have serious consequences. Looking for telltale signs, especially in adolescents and MSM, can help you intervene early and offer behavioral-based treatment.

Table: Categories and Effects of Inhalants

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Issue Date: September 10, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)