Deprescribing Anti-anxiety Medications in Older Adults

Rachel Meyen, MD. Outpatient geriatric psychiatrist, General Mental Health Clinic, Sacramento VA Medical Center. Dr. Meyen has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Our inclination may be to “not rock the boat” when a patient is stable and not misusing prescribed medication. However, tapering anti-anxiety medications in older adults is often a good idea when considering the risks of falls, sedation, and accidents.

Which meds to taper?

The risks of anti-anxiety medications increase with age. Here are some of the medications we use to treat anxiety in the elderly, along with adverse effects that should prompt us to consider discontinuation.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines in older adults increase the risk of falls, altered cognition, oversedation, and drug-drug interactions. They also increase the risk of respiratory depression in patients on opioids. When benzodiazepines are abruptly discontinued, withdrawal can include seizure or death. Benzodiazepines can also cause or aggravate delirium, worsening outcomes in patients with acute medical issues. In short, benzodiazepines are not recommended for older adults (Markota M et al, Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91(11):1632–1639). (Editor’s note: For more on benzodiazepines and older adults, see Q&A on page 1.) The “Z-drugs” (including zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone) are not much safer and increase the risk of falls, abnormal sleep-related behaviors, and rebound insomnia.

SSRIs and SNRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are safer than benzodiazepines, and many are considered the safest pharmacological options in the elderly. However, they too have risks. SSRIs increase the risk of postural sway, falls, fractures, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and bleeding, while SNRIs can cause constipation and lead to a modest increase in blood pressure (van Poelgeest EP et al, Eur Geriatr Med 2021;12(3):585–596).

Anticonvulsants

Other than gabapentin, which is generally well tolerated in the elderly, anticonvulsants increase the risk of drug-drug interactions and toxicity (McGeeney BE, J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38(2 Suppl):S15–S27). Valproic acid can induce thrombocytopenia or hyperammonemia.

Antipsychotics

Although some antipsychotics have high effect sizes in the treatment of anxiety, most geriatric psychiatrists try to avoid them in the elderly due to their side effect profile. Antipsychotics are best avoided in patients with dementia due to the FDA black box warning of an increased risk of death and cerebrovascular events in dementia-related psychosis.

Antipsychotics increase the risk of movement disorders, sedation, muscle stiffness, restlessness, tardive dyskinesia, weight gain, falls, metabolic disturbances, cardiac arrhythmias, and difficulty swallowing (which can lead to aspiration pneumonia). Antipsychotics can also cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Trazodone

Trazodone is commonly prescribed in older adults with dementia with behavioral disturbances to treat agitation, anxiety, irritability, insomnia, or behavioral disturbances. However, it can cause oversedation, which may lead to falls, decreased oral intake, decreased quality of life, and diminished ability to participate in care.

Antihistamines

Hydroxyzine and diphenhydramine are effective nonaddictive anxiolytics, but they can cause oversedation, and they have anticholinergic effects.

Educate before tapering

Before making a decision to taper, I take a careful history to determine the patient’s underlying diagnosis, history of medication trials, current symptoms, remission status, and functioning. I educate patients about the potential dangers of medications before suggesting a taper.

Patients often find education to be motivating. For example, in the EMPOWER trial, older adults with chronic benzodiazepine use were mailed a brief brochure providing education about risks associated with long-term benzodiazepine use and instructions on safe tapering protocols (www.criugm.qc.ca/images/

How to taper

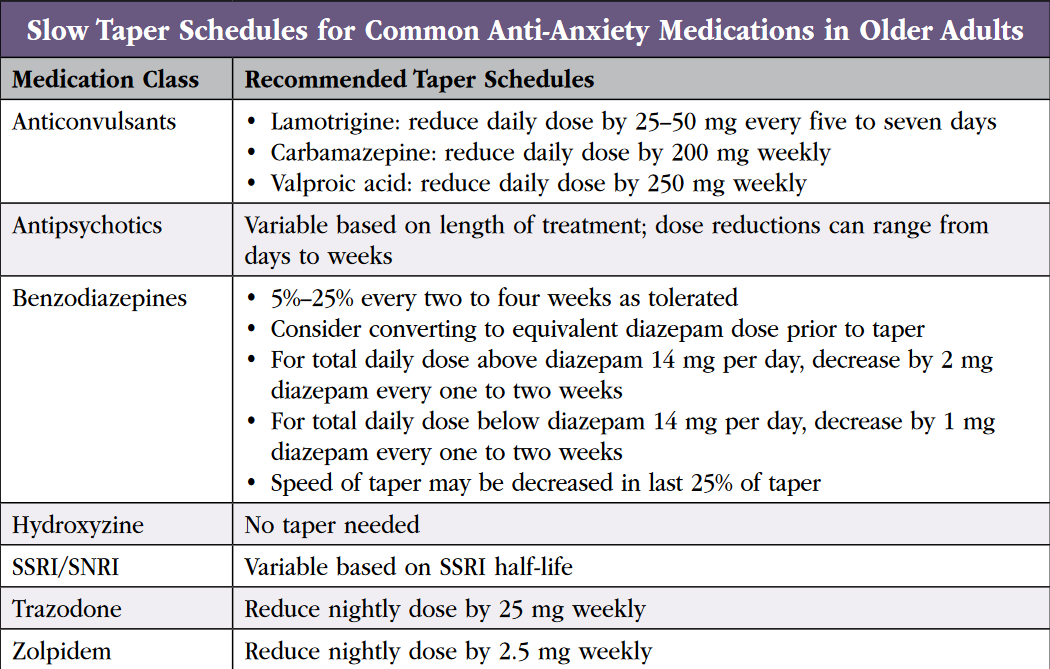

We walk you through practical advice for tapering anti-anxiety medications in the following section. See table on slow taper schedules.

Benzodiazepines

Aim to decrease the dose by 5%–25% every two to four weeks. Some patients will require a slower taper, especially if they have taken benzodiazepines for decades. Alternatively, you can convert to an equivalent dose of the longer-acting diazepam prior to tapering. However, due to its long half-life and buildup of metabolites, this strategy is less appealing in older adults. If you switch to diazepam, for a total daily dose above diazepam 14 mg per day, decrease in 2 mg increments every one to two weeks. For total daily doses below diazepam 14 mg per day, decrease in 1 mg increments every one to two weeks. You may need to go slower in the last 25% of the taper, according to the Ashton manual (www.benzo.org.uk/manual/).

Z-drugs

Taper slowly to avoid rebound insomnia. One study reported that a “stepped approach” was effective, starting with a written letter to the patient from their physician recommending discontinuation of zolpidem, followed by a structured taper combined with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (Bélanger L et al, Sleep Med Clin 2009;4(4):583–592). If your patient is taking sustained-release zolpidem, it’s best to switch to the immediate-release version before tapering, because the latter formulation lets you decrease in smaller increments. In patients taking zolpidem 10 mg at bedtime, reduce by 2.5 mg weekly.

SSRIs and SNRIs

Both SSRIs and SNRIs can cause discontinuation syndrome, which includes flu-like symptoms, “zaps” in the brain, and worsening of mood/anxiety symptoms (which may be misinterpreted as relapse). Although venlafaxine and paroxetine are notorious for their discontinuation symptoms, all SSRIs/SNRIs can cause discontinuation problems. If discontinuation symptoms occur, return to the previous dose at which your patient did not experience symptoms and/or slow the taper. Examples include decreasing sertraline by 25–50 mg every two to six weeks or decreasing venlafaxine by 37.5 mg every two to six weeks.

Anticonvulsants

I recommend tapering off lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and valproic acid if inappropriately prescribed for anxiety, although I would first check that the anticonvulsant is not prescribed for an underlying bipolar disorder. Discontinuation syndrome in anticonvulsants is uncommon, but a taper is recommended to avoid the risk of destabilizing bipolar I disorder (if present) and to reduce the risk of seizures (Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology Prescriber’s Guide. 7th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2020). Decrease lamotrigine daily dose by 25–50 mg every five to seven days, carbamazepine daily dose by 200 mg weekly, and valproic acid daily dose by 250 mg weekly. Other medications may require adjustment due to enzyme induction and drug-drug interactions of anticonvulsants.

Antipsychotics

For patients taking antipsychotics for sleep, cross-titrate to an alternative sleep medication such as trazodone, gabapentin, or low-dose mirtazapine. Otherwise, decrease quetiapine in 12.5–25 mg increments, adjusting the dose every three days to one week. Taper olanzapine in 2.5 mg increments every few days or every week.

Other anti-anxiety medications

Antihistamines can be stopped without a taper. The risk of discontinuation symptoms from stopping “cold turkey” is low. Reduce trazodone by 25 mg weekly as tolerated.

Preferred medications for anxiety

For older adults, pregabalin can be considered, although I prefer the structurally similar but lower-cost gabapentin. Gabapentin 100 mg can be given as needed one to three times daily to treat anxiety, and it can be used at night to promote sleep. The evidence is not very robust for gabapentin, although it is commonly used given its tolerability in the elderly. Be aware that gabapentin is renally cleared, so check creatinine clearance before prescribing.

Buspirone is very well tolerated in the elderly and can be an effective adjuvant to SSRIs for anxiety. Start at 5 mg twice daily and increase by 5 mg/day every few days. The maximum daily dose is 60 mg daily, although many older adults experience benefit at 15–30 mg daily.

Mirtazapine helps with anxiety and sleep. Tolerability is good in older adults, and the side effect of appetite stimulation can be a “two-fer” in patients with anxiety and poor oral intake. Start at 7.5 mg at bedtime and increase in 7.5 mg increments every few days to one week. Mirtazapine 7.5–15 mg primarily targets sleep, and a 15–30 mg dose is usually sufficient to control anxiety in older adults.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)