Home » Genetic Counseling: A Primer for Psychiatrists

Genetic Counseling: A Primer for Psychiatrists

November 1, 2005

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Daniel Carlat, MD

Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no significant relationships with or financial interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Genetic counseling in psychiatry is a tricky proposition, because we are just starting to understand the complexity that underlies the genetic basis of psychiatric disease.

Genetic counseling has traditionally been most useful for single gene disorders like Huntington’s Disease and Tay-Sachs Disease, where the mode of transmission is better understood, and for which there are diagnostic tests. For such diseases, affected patients may wonder about the risks of passing on an illness to their children, while children of affected patients will want to know their statistical risk of developing the disease. Genetic counselors will be able to provide them with plenty of answers and informed guidance.

In psychiatry, the only disease that even approaches this model is Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). For certain variants of familial early-onset AD

(onset before age 60), the mechanism of transmission is just like Huntington’s – that is, autosomal dominant.

Offspring have a 50% chance of inheriting the disease-producing gene variant, and of therefore becoming demented early in life. The genes so far identified, each one of which alone can cause the disease, are presenilin-1, presenilin-2, and beta-amyloid precursor protein. (For a recent review, see Pharmacological Research 2004; 50: 385-396.) If you have a patient who comes to you with a history of family members developing AD before age 60 (the average age of onset for early AD is about 50), you should tell them about these genes and refer them to a genetic counselor for further evaluation and possible testing.

What about testing for the more common version of AD, late-onset AD? Researchers have discovered that variants of the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene, located on chromosome 19, can lead to a higher risk of becoming demented eventually. Basically, if you are heterozygous for the bad version of ApoE (which is denoted e4), you have a 30% chance of getting AD by age 80; if you’re homozygous, you may stand as high as a 90% chance (NEJM 2003; 348:1356-1364). However, whether to offer such testing to patients is subjects to controversy, as TCR has explored in a prior issue (TCR October 2003). Why? Because knowing you are homozygous for e4 leads to terrible problems but no solutions. You will become demoralized to know that you are headed toward almost certain AD someday, but medicine at this point has little to offer you in the way of anti-AD prophylaxis (see TCR August 2005 for an update on this research). Of course, this same issue applies to both Huntington’s and earlyonset AD, but since the predictive validity of genetic testing for these diseases is so high, many geneticists will recommend testing, as long as there is plenty of pre- and post- testing counseling.

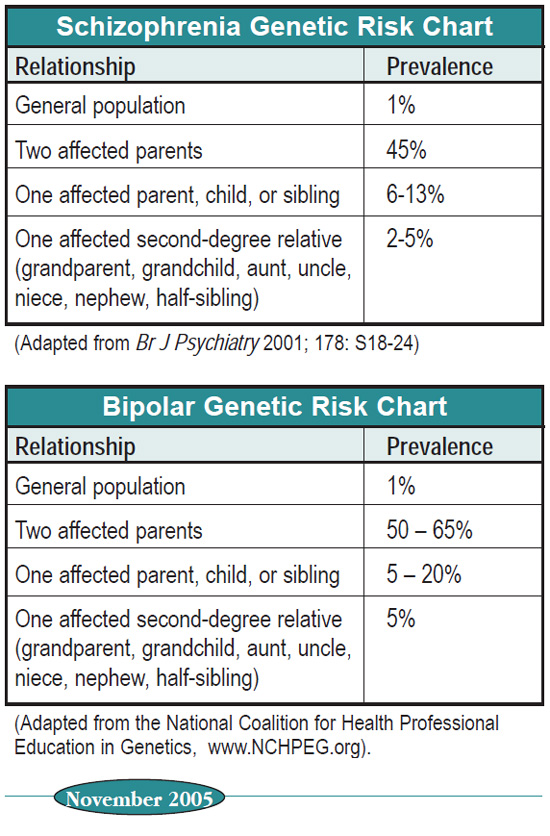

What about schizophrenia and bipolar disorder? Since there is as yet no predictive genetic testing available, genetic counselors resort to what is known as discussing “empiric risks,” which means synthesizing results of family studies and discussing these figures with patients. Recurrence risks for simple family relationships are known for some psychiatric disorders, as depicted in the charts.

The use of these charts is fairly self-explanatory. Suppose one of your patients has a father with schizophrenia, and asks you if that means she will become schizophrenic too. You could review the ranges listed in the chart as the basis for a preliminary discussion of her risk. As you can see, having a single affected parent means that she has a lifetime risk in the range of 6-13%. This is well above the population baseline prevalence of about 1%. If your patient reports having had two schizophrenic parents, her risk goes up to close to 50%. The figures for bipolar disorder are similar.

Of course, there’s a lot more to genetic counseling than reading off a table, which explains why genetic counselors have to spend two years getting a master’s degree in the field. There are a variety of details to go over that you will likely have neither the time nor the expertise to go into. For example, just because your patient reports that her parents were schizophrenic doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s so. Conversely, some patients may have had mentally ill relatives and not know the diagnosis, often because diagnostic and treatment practices in psychiatry have changed drastically over time. It’s often possible to provisionally diagnose a patient’s relative retrospectively, but that requires more time than you may have.

Another issue is that the numbers on the risk charts are derived from studies of families that may be different from your patient’s, and unless you spend time reading these studies (as genetic specialists do), you won’t know how to modify the risk figures you quote. For example, suppose your patient describes a family scenario that isn’t listed on the chart, such as a mother with schizophrenia, a father with bipolar disorder, and a brother with panic disorder? A good genetics counselor will spend time scouring the literature for studies that may yield numbers more directly applicable to such a person.

There are innumerable other variations on the family history theme that you may not be prepared to deal with. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try your hand at “amateur” genetic counseling – just realize when you’ve reached the limits of your helpfulness, and be prepared to refer. The National Society of Genetic Counselors offers a nationwide directory of counselors at http://www.nsgc.org/resourcelink.asp.

TCR VERDICT:

Genetic counseling: Useful but inexact

General PsychiatryGenetic counseling has traditionally been most useful for single gene disorders like Huntington’s Disease and Tay-Sachs Disease, where the mode of transmission is better understood, and for which there are diagnostic tests. For such diseases, affected patients may wonder about the risks of passing on an illness to their children, while children of affected patients will want to know their statistical risk of developing the disease. Genetic counselors will be able to provide them with plenty of answers and informed guidance.

In psychiatry, the only disease that even approaches this model is Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). For certain variants of familial early-onset AD

(onset before age 60), the mechanism of transmission is just like Huntington’s – that is, autosomal dominant.

Offspring have a 50% chance of inheriting the disease-producing gene variant, and of therefore becoming demented early in life. The genes so far identified, each one of which alone can cause the disease, are presenilin-1, presenilin-2, and beta-amyloid precursor protein. (For a recent review, see Pharmacological Research 2004; 50: 385-396.) If you have a patient who comes to you with a history of family members developing AD before age 60 (the average age of onset for early AD is about 50), you should tell them about these genes and refer them to a genetic counselor for further evaluation and possible testing.

Of course, there’s a lot more to genetic counseling than reading off a table, which explains why genetic counselors have to spend two years getting a master’s degree in the field.

What about testing for the more common version of AD, late-onset AD? Researchers have discovered that variants of the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene, located on chromosome 19, can lead to a higher risk of becoming demented eventually. Basically, if you are heterozygous for the bad version of ApoE (which is denoted e4), you have a 30% chance of getting AD by age 80; if you’re homozygous, you may stand as high as a 90% chance (NEJM 2003; 348:1356-1364). However, whether to offer such testing to patients is subjects to controversy, as TCR has explored in a prior issue (TCR October 2003). Why? Because knowing you are homozygous for e4 leads to terrible problems but no solutions. You will become demoralized to know that you are headed toward almost certain AD someday, but medicine at this point has little to offer you in the way of anti-AD prophylaxis (see TCR August 2005 for an update on this research). Of course, this same issue applies to both Huntington’s and earlyonset AD, but since the predictive validity of genetic testing for these diseases is so high, many geneticists will recommend testing, as long as there is plenty of pre- and post- testing counseling.

What about schizophrenia and bipolar disorder? Since there is as yet no predictive genetic testing available, genetic counselors resort to what is known as discussing “empiric risks,” which means synthesizing results of family studies and discussing these figures with patients. Recurrence risks for simple family relationships are known for some psychiatric disorders, as depicted in the charts.

Table: Schizophrenia Genetic Risk Chart

Table: Bipolar Genetic Risk Chart

The use of these charts is fairly self-explanatory. Suppose one of your patients has a father with schizophrenia, and asks you if that means she will become schizophrenic too. You could review the ranges listed in the chart as the basis for a preliminary discussion of her risk. As you can see, having a single affected parent means that she has a lifetime risk in the range of 6-13%. This is well above the population baseline prevalence of about 1%. If your patient reports having had two schizophrenic parents, her risk goes up to close to 50%. The figures for bipolar disorder are similar.

Of course, there’s a lot more to genetic counseling than reading off a table, which explains why genetic counselors have to spend two years getting a master’s degree in the field. There are a variety of details to go over that you will likely have neither the time nor the expertise to go into. For example, just because your patient reports that her parents were schizophrenic doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s so. Conversely, some patients may have had mentally ill relatives and not know the diagnosis, often because diagnostic and treatment practices in psychiatry have changed drastically over time. It’s often possible to provisionally diagnose a patient’s relative retrospectively, but that requires more time than you may have.

Another issue is that the numbers on the risk charts are derived from studies of families that may be different from your patient’s, and unless you spend time reading these studies (as genetic specialists do), you won’t know how to modify the risk figures you quote. For example, suppose your patient describes a family scenario that isn’t listed on the chart, such as a mother with schizophrenia, a father with bipolar disorder, and a brother with panic disorder? A good genetics counselor will spend time scouring the literature for studies that may yield numbers more directly applicable to such a person.

There are innumerable other variations on the family history theme that you may not be prepared to deal with. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try your hand at “amateur” genetic counseling – just realize when you’ve reached the limits of your helpfulness, and be prepared to refer. The National Society of Genetic Counselors offers a nationwide directory of counselors at http://www.nsgc.org/resourcelink.asp.

TCR VERDICT:

Genetic counseling: Useful but inexact

Issue Date: November 1, 2005

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)