Home » A Narcolepsy Primer, With a Focus on Xyrem

A Narcolepsy Primer, With a Focus on Xyrem

September 1, 2015

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Talia Puzantian, PharmD, BCPP

Clinical psychopharmacology consultant in private practice, Los Angeles, CA. www.taliapuzantian.com

Dr. Puzantian has disclosed that she has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

Daniel Carlat, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Publisher, The Carlat Report.

Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

Narcolepsy affects about 1 out of 2000 people, for a prevalence rate of 0.05%. This puts it officially in the category of rare diseases. It’s about as common as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, or polycythemia vera, just to put it in perspective. So why are we asking you to read about such a rare disorder? Partly because there’s a lot of comorbidity between narcolepsy and most psychiatric disorders. And partly because Jazz Pharmaceuticals is placing lots of ads in psychiatric journals urging us to diagnose more narcolepsy so that we’ll use their new drug Xyrem. It’s probably better for you to get your narcolepsy info here than on Jazz’s supposedly “educational” website. (Also see Leschziner G, Pract Neurol 2014;14:323–331 for a comprehensive unbiased review of narcolepsy).

There are two types of narcolepsy. Both types include the core feature, which is excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). This sensation of sleepiness must occur most of the time—the official DSM-5 threshold is at 3 days per week for 3 months. (By the way, the Greek etymology of the word narcolepsy comes from narke, which means stupor, and lepsis, or seizure. Narcolepsy, then, is literally “to be seized by sleep”.)

Narcolepsy without cataplexy. Also known as narcolepsy type 2, narcolepsy without cataplexy affects 30% of narcoleptics, and the symptoms are primarily profound sleepiness. These patients will tell you that they could fall asleep at any point throughout the day, and that they feel better after naps. Other symptoms sometimes seen in narcolepsy include hypnagogic hallucinations (vivid dreamlike images while falling asleep) and sleep paralysis (a temporary inability to move or speak just before falling asleep or just after waking up).

Narcolepsy with cataplexy

Narcolepsy with cataplexy (narcolepsy type 1) is the most common type, afflicting 70% of all narcolepsy victims. These patients have EDS as described above along with cataplexy, which is truly one of the most bizarre symptoms in medicine: the sudden loss of muscle tone, triggered by strong emotions, usually positive ones, such as laughing and joking. A common report from patients is “my knees sometimes buckle when I laugh.” But it can be more severe, such as falling right down. The patient does not faint, and is conscious throughout the attack, which usually lasts a minute or two. Interestingly, narcolepsy type 1 is associated with a specific biomarker—low levels of orexin (also known as hypocretin) in the spinal fluid. Orexin is released from the brain into the bloodstream when we are awake, and its function seems to be to ensure that we are awake when we’re supposed to be. Type 2 narcoleptics do not have low levels of orexin.

(By the way, you may recall from the October 2014 TCPR that Merck’s new sleeping pill, branded as Belsomra for the chemical name suvorexant, is an orexin receptor antagonist, a mechanism which makes sense given the neurobiology described above.)

If your patient has EDS without cataplexy or any other narcolepsy symptoms, then you’re looking at something other than narcolepsy—namely, hypersomnia. And there are many potential causes of hypersomnia, including other sleep disorders (sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome or periodic limb movement disorder, idiopathic hypersomnia, sleep phase disorders), depression, some medical disorders, and the effect of sedating meds or alcohol. But probably the most common cause of sleepiness is simply sleep deprivation and fatigue (see TCPR, November 2012 for an entire article on how to assess and treat fatigue). Reviewing a patient’s sleep patterns and sleep hygiene is just as important as sending them for sleep study in the workup for narcolepsy.

Treatment of Narcolepsy

Sleep hygiene. While medications are the mainstay of treatment, basic sleep hygiene and other commonsense measures should be part of the program. For example, is the patient taking meds or substances that can worsen sleepiness? If so, consider changing the dosing time, discontinuing it, or switching to something else. Occasional short scheduled naps can help to relieve the sleepiness and improve daytime functioning.

Medications. FDA-approved medications for the EDS symptoms of narcolepsy include the wake-promoting agents modafinil (Provigil) and armodafinil (Nuvigil), as well as the stimulants dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), methylphenidate (Ritalin), and mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall). Provigil and Nuvigil are usually the favored agents because they are better tolerated and have lower abuse potential.

Cataplexy is harder to treat. Antidepressants have shown some efficacy—including tricyclics, SSRIs, and venlafaxine. Wake promoters and stimulants are probably less effective.

Xyrem (sodium oxybate). Which brings us to the new kid on the block, Xyrem—the first medication FDA-approved for both cataplexy and EDS. It is a Schedule III controlled substance and is the sodium salt of gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), widely known as a “date rape” drug.

Why would an extremely potent tranquilizer work for narcolepsy? It’s not clear, but it apparently repairs and consolidates sleep, so that narcoleptics spend less time in REM and more time in deep sleep. A good robust sleep with the right sleep architecture leads to less daytime sleepiness, and less of a tendency to have attacks of cataplexy.

How good are the Xyrem efficacy data? A 4-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluated Xyrem 3-9 g for cataplexy in 136 patients with narcolepsy type 1. 85% of these patients were also taking stimulants, making it difficult to determine the therapeutic effects of Xyrem alone. Patients taking 3 g of Xyrem did not fare better than those taking placebo. But those taking 6 g and 9 g had reductions in the frequency of cataplexy attacks (placebo patients reduced an average of 20.5 weekly attacks by 4 while Xyrem 6 g and 9 g patients reduced 23 weekly attacks by 10 and 16, respectively, but only the 9 g dose was significantly better than placebo) (The U.S. Xyrem Multicenter Study Group, Sleep 2002;25(1):42–9). And, while the effects on cataplexy are immediate, the improvement in EDS may take up to 8 weeks according to a study of 228 patients with narcolepsy (78% were also taking stimulants) (Black J et al, J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6(6):596–602).

One of the more interesting and useful studies compared the effectiveness of Xyrem used alone to modafinil used alone and to Xyrem combined with modafinil in treating EDS in 270 patients with narcolepsy who were previously treated with modafinil alone. This study found that Xyrem alone was just as effective as modafinil alone for EDS but that the combination was significantly better than either medication used alone. So, in the real world, it’s likely that patients taking Xyrem will also be taking either a wake promoter or stimulant (Black J and Houghton WC, Sleep 2006;29(7):939–46).

So Xyrem works well—but there are significant side effects. In the clinical trials, the most common side effects were nausea and vomiting, dizziness, somnolence, and urinary incontinence. The real problems with the drug are its high abuse potential and the possibility of respiratory depression, coma, and death when used at high doses and when combined with alcohol. Its close cousin, GHB, the date rape drug, causes very rapidly acting euphoric effects and often amnesia for events while intoxicated.

Because of its abuse potential and risk of serious side effects, Xyrem can only be dispensed through the manufacturer-funded “Xyrem Success Program,” which requires both the patient and the prescriber to be enrolled; the medication is distributed from a centralized pharmacy.

Xyrem is more complicated than the average medication for patients. It’s taken as an oral solution that is diluted by the patient with water using a provided syringe and vial. The patient prepares two nightly doses, gets in bed, and takes the 1st dose (usually started as 2.25 g); the 2nd dose is taken 2.5–4 hours later while still lying down in bed. The second dose is necessary because Xyrem has an extremely short half life. Some patients may wake up on their own for this 2nd dose, but many will need to set an alarm. The dose is titrated at weekly intervals to the usual range of 6–9 g per night (more details here).

TCPR Verdict: Xyrem is probably the most effective medication for patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy, and it’s often used by specialists as a first-line agent for this. But, for narcolepsy without cataplexy, start with a stimulant, and use Xyrem only if that doesn’t work. It’s an expensive drug (a 10-day bottle of solution is about $3500) and the risks of respiratory depression and abuse of the drug are significant.

DSM-5 Criteria for Narcolepsy

The core criterion A is an “irrepressible need for sleep” that occurs most of the time—at least 3 days per week for 3 months.

The patient also must meet at least one of the following B criteria:

General PsychiatryThere are two types of narcolepsy. Both types include the core feature, which is excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). This sensation of sleepiness must occur most of the time—the official DSM-5 threshold is at 3 days per week for 3 months. (By the way, the Greek etymology of the word narcolepsy comes from narke, which means stupor, and lepsis, or seizure. Narcolepsy, then, is literally “to be seized by sleep”.)

Narcolepsy without cataplexy. Also known as narcolepsy type 2, narcolepsy without cataplexy affects 30% of narcoleptics, and the symptoms are primarily profound sleepiness. These patients will tell you that they could fall asleep at any point throughout the day, and that they feel better after naps. Other symptoms sometimes seen in narcolepsy include hypnagogic hallucinations (vivid dreamlike images while falling asleep) and sleep paralysis (a temporary inability to move or speak just before falling asleep or just after waking up).

Narcolepsy with cataplexy

Narcolepsy with cataplexy (narcolepsy type 1) is the most common type, afflicting 70% of all narcolepsy victims. These patients have EDS as described above along with cataplexy, which is truly one of the most bizarre symptoms in medicine: the sudden loss of muscle tone, triggered by strong emotions, usually positive ones, such as laughing and joking. A common report from patients is “my knees sometimes buckle when I laugh.” But it can be more severe, such as falling right down. The patient does not faint, and is conscious throughout the attack, which usually lasts a minute or two. Interestingly, narcolepsy type 1 is associated with a specific biomarker—low levels of orexin (also known as hypocretin) in the spinal fluid. Orexin is released from the brain into the bloodstream when we are awake, and its function seems to be to ensure that we are awake when we’re supposed to be. Type 2 narcoleptics do not have low levels of orexin.

(By the way, you may recall from the October 2014 TCPR that Merck’s new sleeping pill, branded as Belsomra for the chemical name suvorexant, is an orexin receptor antagonist, a mechanism which makes sense given the neurobiology described above.)

If your patient has EDS without cataplexy or any other narcolepsy symptoms, then you’re looking at something other than narcolepsy—namely, hypersomnia. And there are many potential causes of hypersomnia, including other sleep disorders (sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome or periodic limb movement disorder, idiopathic hypersomnia, sleep phase disorders), depression, some medical disorders, and the effect of sedating meds or alcohol. But probably the most common cause of sleepiness is simply sleep deprivation and fatigue (see TCPR, November 2012 for an entire article on how to assess and treat fatigue). Reviewing a patient’s sleep patterns and sleep hygiene is just as important as sending them for sleep study in the workup for narcolepsy.

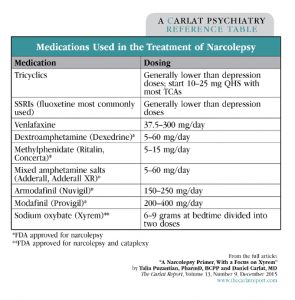

Table: Medications Used in the Treatment of Narcolepsy

Click to view full-size PDF version.

Treatment of Narcolepsy

Sleep hygiene. While medications are the mainstay of treatment, basic sleep hygiene and other commonsense measures should be part of the program. For example, is the patient taking meds or substances that can worsen sleepiness? If so, consider changing the dosing time, discontinuing it, or switching to something else. Occasional short scheduled naps can help to relieve the sleepiness and improve daytime functioning.

Medications. FDA-approved medications for the EDS symptoms of narcolepsy include the wake-promoting agents modafinil (Provigil) and armodafinil (Nuvigil), as well as the stimulants dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), methylphenidate (Ritalin), and mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall). Provigil and Nuvigil are usually the favored agents because they are better tolerated and have lower abuse potential.

Cataplexy is harder to treat. Antidepressants have shown some efficacy—including tricyclics, SSRIs, and venlafaxine. Wake promoters and stimulants are probably less effective.

Xyrem (sodium oxybate). Which brings us to the new kid on the block, Xyrem—the first medication FDA-approved for both cataplexy and EDS. It is a Schedule III controlled substance and is the sodium salt of gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), widely known as a “date rape” drug.

Why would an extremely potent tranquilizer work for narcolepsy? It’s not clear, but it apparently repairs and consolidates sleep, so that narcoleptics spend less time in REM and more time in deep sleep. A good robust sleep with the right sleep architecture leads to less daytime sleepiness, and less of a tendency to have attacks of cataplexy.

How good are the Xyrem efficacy data? A 4-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluated Xyrem 3-9 g for cataplexy in 136 patients with narcolepsy type 1. 85% of these patients were also taking stimulants, making it difficult to determine the therapeutic effects of Xyrem alone. Patients taking 3 g of Xyrem did not fare better than those taking placebo. But those taking 6 g and 9 g had reductions in the frequency of cataplexy attacks (placebo patients reduced an average of 20.5 weekly attacks by 4 while Xyrem 6 g and 9 g patients reduced 23 weekly attacks by 10 and 16, respectively, but only the 9 g dose was significantly better than placebo) (The U.S. Xyrem Multicenter Study Group, Sleep 2002;25(1):42–9). And, while the effects on cataplexy are immediate, the improvement in EDS may take up to 8 weeks according to a study of 228 patients with narcolepsy (78% were also taking stimulants) (Black J et al, J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6(6):596–602).

One of the more interesting and useful studies compared the effectiveness of Xyrem used alone to modafinil used alone and to Xyrem combined with modafinil in treating EDS in 270 patients with narcolepsy who were previously treated with modafinil alone. This study found that Xyrem alone was just as effective as modafinil alone for EDS but that the combination was significantly better than either medication used alone. So, in the real world, it’s likely that patients taking Xyrem will also be taking either a wake promoter or stimulant (Black J and Houghton WC, Sleep 2006;29(7):939–46).

So Xyrem works well—but there are significant side effects. In the clinical trials, the most common side effects were nausea and vomiting, dizziness, somnolence, and urinary incontinence. The real problems with the drug are its high abuse potential and the possibility of respiratory depression, coma, and death when used at high doses and when combined with alcohol. Its close cousin, GHB, the date rape drug, causes very rapidly acting euphoric effects and often amnesia for events while intoxicated.

Because of its abuse potential and risk of serious side effects, Xyrem can only be dispensed through the manufacturer-funded “Xyrem Success Program,” which requires both the patient and the prescriber to be enrolled; the medication is distributed from a centralized pharmacy.

Xyrem is more complicated than the average medication for patients. It’s taken as an oral solution that is diluted by the patient with water using a provided syringe and vial. The patient prepares two nightly doses, gets in bed, and takes the 1st dose (usually started as 2.25 g); the 2nd dose is taken 2.5–4 hours later while still lying down in bed. The second dose is necessary because Xyrem has an extremely short half life. Some patients may wake up on their own for this 2nd dose, but many will need to set an alarm. The dose is titrated at weekly intervals to the usual range of 6–9 g per night (more details here).

TCPR Verdict: Xyrem is probably the most effective medication for patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy, and it’s often used by specialists as a first-line agent for this. But, for narcolepsy without cataplexy, start with a stimulant, and use Xyrem only if that doesn’t work. It’s an expensive drug (a 10-day bottle of solution is about $3500) and the risks of respiratory depression and abuse of the drug are significant.

DSM-5 Criteria for Narcolepsy

The core criterion A is an “irrepressible need for sleep” that occurs most of the time—at least 3 days per week for 3 months.

The patient also must meet at least one of the following B criteria:

- Cataplexy.

- Low levels of orexin in the spinal fluid (requires a lumbar puncture).

- A positive sleep lab test—either a polysomnogram (done at night) showing unusually rapid onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, with a latency, or delay, of 15 minutes or less; or a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) done during the day, in which the patient is asked to take 4–5 short naps, at 2-hour intervals, over the course of a day. Narcolepsy is consistent with either: 1. Falling asleep within 8 minutes of laying down (the normal sleep latency is at least 12 minutes); or 2. Slipping immediately into REM sleep two times during the testing period.

KEYWORDS psychopharmacology_tips sleep_disorders

Issue Date: September 1, 2015

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)