Home » Assessing and Diagnosing Tic Disorders

Assessing and Diagnosing Tic Disorders

March 1, 2017

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Erica Greenberg, MD

Assistant psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital; Pediatric Neuropsychiatry and Immunology Program within the OCD and Related Disorders Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

Dr. Greenberg has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Erica Greenberg, MD

Assistant psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital; Pediatric Neuropsychiatry and Immunology Program within the OCD and Related Disorders Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

Dr. Greenberg has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CCPR: Would you describe your clinical work in tic disorders and how that operates? I think readers will want to know about the number of patients you see and how the clinic is structured.

Dr. Greenberg: I work in the obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and related disorders program, and I see both kids with tics and OCD or OCD-related disorders as well as those with symptoms consistent with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) or pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). I’ll typically see two to three new patients a week who fit somewhere in the OCD, tic, or PANDAS spectrum. And then I’ll see another 10 or so follow-ups who also have those conditions.

CCPR: Give me a quick lesson in the larger field of tic disorders versus Tourette’s disorder (TD). Are tic disorders a larger category, with Tourette’s being one of the disorders in that domain?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes. TD is one of only a few disorders in the tic disorders category, the others being persistent motor or vocal tic disorder and provisional tic disorder. All one needs to have a TD diagnosis is 2 or more motor tics, and 1 or more vocal tic, that have persisted for at least a year (with tic onset before age 18). About 15% of kids will have transient tics at some point in their childhood, usually during late elementary school; many will disappear within a year, and that’s called provisional tic disorder (Black KJ et al, F1000Research 2016;5:696. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8428.1). There really isn’t much of a difference between motor or vocal tic disorder and TD: The main diagnostic distinction is between the kids who have a tic for a short amount of time and in whom it usually disappears around age 9 vs those with chronic tics. I think of it as more of a spectrum of tic disorders, with TD at the more severe end and typically, though not always, with more tics in general.

CCPR: How common is Tourette’s disorder?

Dr. Greenberg: The prevalence of TD is about 0.5%, and an additional 1%–2% of the population has chronic tic disorder, so it’s a pretty rare syndrome (Scharf JM et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51(2):192–201.e5). That said, about 15% of kids will have a tic at some point, but if it doesn’t last for a year, it doesn’t meet the criteria.

CCPR: As a doctor working in a tertiary academic center, your practice is going to be different from a typical child psychiatrist’s. How common is it for parents to bring in a child specifically for a tic problem?

Dr. Greenberg: For a typical child psychiatrist, the more likely scenario is that a parent will bring in a child with OCD or ADHD symptoms, and the clinician will notice some tics and ask questions, especially if he or she is aware of the Tourette’s disorder triad of tics, OCD, and ADHD.

CCPR: So, if we do see a kid with OCD, we should be thinking about tics.

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, definitely. About 15%–25% of kids with OCD will have tics, especially if the OCD is early onset, meaning prepubertal/early adolescence (Rizzo R et al, J Child Neurol 2014;29(10):1383–1389). In fact, early-onset OCD is genetically linked with TD. So, just in terms of the genetics, if a parent has TD, the child might have OCD or vice versa.

CCPR: And there’s also a connection between ADHD and tics?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes. Again, around 15%–20% of kids with ADHD will have tics, and about 60% or more of TD patients have ADHD (Bloch MH et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48(9):884–893). The point is, a lot of kids with ADHD will have tics; so, if you treat them with a stimulant and see tics, it’s not necessarily that the stimulant caused the tics—often, the tics might have developed anyway.

CCPR: Can you walk us through a typical evaluation?

Dr. Greenberg: Sure. I have 90-minute intake slots, and I see the kids and the parents together, then each separately, and then bring them together in the end. I usually start by asking about the typical features of tics. Do they come and go or “wax and wane”? Do they occur in bouts? Do they “jump” or change in location over time? Is it like an itch the child needs to scratch? Does talking about them make them worse? I do sometimes start with more open-ended questions, but sometimes asking the more specific questions helps to build rapport, because I’m validating a symptom. A lot of these kids will be told over and over, “Just stop that. Why are you doing that? That’s annoying; cut it out.” And they’ll say they can’t. Asking about tic features as legitimate symptoms builds immediate trust. From there, I typically ask about comorbidities.

CCPR: How do you approach that?

Dr. Greenberg: I’ll start by saying, “A lot of kids I see who have tics often have other things going on. Some of them have a lot of difficulty with worrying or having to repeat certain things, or with mood or anger, or with paying attention. Do any of those sound familiar to you?” They might say yes or no. And then I’ll try to go syndrome by syndrome to determine if, given the fact that they have tics, they have any of the other common comorbidities. Since many parents have heard of it, I might just ask, “Have you heard of OCD? What do you know about it? Are there any OCD symptoms you think your child might have?” And, depending on their answer, I’ll then ask more pointed questions such as about excessive handwashing, checking, or confessing behaviors. And I’ll bring it up with the child again when we talk separately.

CCPR: So the separate interview is key to your evaluation?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes. Both sets of answers will help determine what to treat first. In the case of OCD, I’ll ask the child directly, “Do you feel like you have unwanted thoughts or urges that get stuck in your head that you just can’t get out? And if you do, do you feel like you need to do something or think something to get rid of it, or that if you don’t, you might worry something bad might happen?” The parents are not always aware of the child’s thinking in this respect. And often the parents and the kid will have different views of the problem. A parent may come in and say, “My kid is ticcing all the time. I worry that kids at school make fun of him. I tell him to stop.” Whereas, if you ask the kid, he will say, “Actually, the tics don’t really bother me. I told my friends it’s just something I do. What really bothers me is that I have these thoughts that I can’t get out of my head, or I’m really anxious or I can’t concentrate.”

CCPR: Are there any assessment tools that you use?

Dr. Greenberg: I tend to give parents a Vanderbilt form to fill out, which not only assesses ADHD symptoms but also disruptive behavior disorders that affect about 25% of kids with TD (available for download at http://www.nichq.org/childrens-health/adhd/resources/vanderbilt-assessment-scales). A good number of them have intermittent explosive disorder. Often these are the kids who will have a rage reaction that might last minutes to an hour, completely out of proportion to the trigger. Afterwards, they are extremely apologetic and feel really bad. These aren’t kids who are chronically irritable, purposely breaking things, getting in trouble; it’s almost like they lose themselves in their rage.

CCPR: How important is it to actually see the child ticcing during the evaluation?

Dr. Greenberg: A lot of kids can suppress tics in the doctor’s office or in school; that certainly does not mean they don’t have them. Kids with tics can hold them in for a while; it’s like holding back a sneeze or an itch.

CCPR: What other disorders do you screen for?

Dr. Greenberg: Anxiety disorders occur in about 30% in people with TD (Coffey B et al, Adv Neurol 1992;58:95–104), so in addition to asking about amount of worrying in the office, I like to give the SCARED (the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders), which can be helpful in parsing out generalized anxiety vs separation anxiety or other disorders (available for download at http://www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/content.asp?id=2333). I always make sure to do a full depression screen, including suicidality. This can get tricky in patients with OCD, because the patient might have aggressive obsessions, like “What if I kill myself?” or “What if I stab my mom?” I try to assess whether these are ego-dystonic, intrusive thoughts (and thus part of the child’s OCD) or if they are products of depression. It is even more complicated because those with TD and comorbid OCD tend to have increased rates of aggressive obsessions (in addition to increased symmetry, sexuality, and religiosity obsessions) compared to those without comorbid tics.

CCPR: What about the motor tics being potentially confused with self-harm movements? Is that an issue?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, and that too can be complicated. I have a number of kids who have tics that involve hitting themselves. This is due to some sort of internal “itch” or sensation that they feel is only relieved by doing this. If you ask them, they don’t want to be doing it. The word we often use is “unvoluntary”—it’s not quite involuntary, nor is it voluntary. But it’s difficult to suppress, and the bad feeling of suppressing it sometimes outweighs the feeling of slamming your hand to your chest. This is different from kids who have self-injurious behavior where the action is more deliberate and purposeful.

CCPR: TD is also famous for coprolalia (ie, swearing tics). Is that an important part of the diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg: While coprolalia probably is the most well-known symptom, actually that particular tic occurs in only about 15% of those with TD (Cohen S et al, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2013;37(6):997–1007. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.013). It’s informative if present, but not all that reliable in making the diagnosis. If you are looking for that symptom to make the diagnosis, you will miss a lot of kids!

CCPR: At what point do you actually feel like you’ve ascertained that a patient has Tourette’s disorder versus a tic disorder?

Dr. Greenberg: To make that distinction, I ask about the history over time. As long as it’s been at least a year, even if the tics come and go, and the child has had at least 2 motor tics—it could be eye blinking or shoulder shrugging—and at least 1 vocal tic, such as sniffing or throat clearing, then I would say that’s TD. A quick trick that can often be helpful is asking whether the patient is making the movement because of a thought or feeling (more OCD-like) or to relieve a bodily sensation (more tic-like). Oftentimes, kids with “Tourettic OCD” (meaning those who have OCD with tics) will describe feelings of incompleteness and need to do a compulsion until things feel “just right.” These are called “Not Just Right Experience” obsessions/compulsions, or NJREs for short.

CCPR: Is there a particular age group you tend to see?

Dr. Greenberg: Many times it’s 10-year-olds, because that’s about the age when the tics tend to escalate in frequency and intensity. But, if you ask the child or parents to think back—“Do you remember anything like this when they were 4 or 5?”—the parent might say, “Maybe,” and the kid might say, “Yeah, I used to blink a lot.” So a lot of times the tics have been there for a while; they just didn’t cause any problems, or parents thought they were secondary to a cold and missed them as a symptom.

CCPR: So this remains a clinical diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, the main way to diagnose TD and all tic disorders is through a good, thorough history. You don’t really need to do any other labs or tests, unless you elicit signs and symptoms that are unexpected, such as an abnormal neurological exam. What’s also important in tics is that the child is making the movement as opposed to hemiballismus or other movement disorders such as chorea or Parkinson movements, where the body is sort of doing it without the brain. The child is the one in charge of tics: Kids (often) know they are ticcing; it’s just that they have trouble stopping. Another really helpful tenet about tics in making a TD diagnosis is their history. Classically, tics tend to occur: 1) motor before vocal; 2) simple before complex; 3) head/neck/shoulders and outwards. It would be rare to see someone with only a complex vocal tic who never had a history of eye blinking or shoulder shrugging.

CCPR: As an expert, you have a pretty rich vocabulary for asking about all the different ways kids are ticcing, whereas clinicians with less experience might not. Can you share some of the distinctions you make?

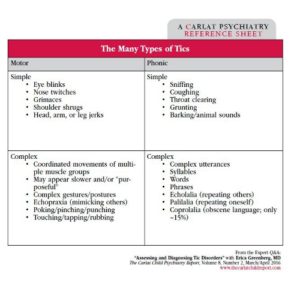

Dr. Greenberg: Definitely. The accompanying table separates tics into motor and phonic as well as simple and complex. Of course, kids may have plenty of different tics, but if I ask about one that is recurrent and consistent, the kid should be able to demonstrate the moment voluntarily. Most kids around 10 years old can identify what’s called a “premonitory urge”; that’s the sensation they feel in their body before they tic, that the tic is typically trying to relieve. So, around that age, they may say, “I have this feeling that I can’t get rid of unless I do the movement.” Younger kids often will say, “I don’t know why I’m doing it; I just have to.”

CCPR: I imagine where it gets tricky is in making the comorbid diagnoses.

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, that’s generally where I end up focusing much of my interview, because what you don’t know, for instance, is whether the kids are so distractible simply because they are ticcing all the time. Are they anxious because the tics are preventing them from concentrating and causing them to do badly in class, or is their anxiety separate and co-occurring with and possibly exacerbating the tics?

CCPR: Those distinctions are important but often harder to clarify.

Dr. Greenberg: Correct. And, because these are kids, the comorbid disorders develop over time, so you might not have hit the period where you would necessarily see the other symptoms yet. As an example, OCD tends to maximize in severity about 2 years after tics maximize in their severity. So you just might not be in the period where they are experiencing the symptoms yet, or there might be little signs of it, but you don’t know. Or maybe they’re having a reactive, adjustment-based depression as opposed to a more innate, genetic depression. Those are the situations where I feel less comfortable making definitive diagnoses at the first appointment.

CCPR: Any closing advice?

Dr. Greenberg: The numbers vary, but about 60%–80% of kids will grow out of their tics, especially by their twenties. So, in general, clinicians can be pretty reassuring to parents. The more severe the tics are at younger ages, the less chance a person will grow out of it, but it’s not a perfect correlation. So it’s one of those disorders for which you can offer some sort of hope that eventually symptoms will lessen or even go away completely.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Greenberg.

Child PsychiatryDr. Greenberg: I work in the obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and related disorders program, and I see both kids with tics and OCD or OCD-related disorders as well as those with symptoms consistent with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) or pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). I’ll typically see two to three new patients a week who fit somewhere in the OCD, tic, or PANDAS spectrum. And then I’ll see another 10 or so follow-ups who also have those conditions.

CCPR: Give me a quick lesson in the larger field of tic disorders versus Tourette’s disorder (TD). Are tic disorders a larger category, with Tourette’s being one of the disorders in that domain?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes. TD is one of only a few disorders in the tic disorders category, the others being persistent motor or vocal tic disorder and provisional tic disorder. All one needs to have a TD diagnosis is 2 or more motor tics, and 1 or more vocal tic, that have persisted for at least a year (with tic onset before age 18). About 15% of kids will have transient tics at some point in their childhood, usually during late elementary school; many will disappear within a year, and that’s called provisional tic disorder (Black KJ et al, F1000Research 2016;5:696. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8428.1). There really isn’t much of a difference between motor or vocal tic disorder and TD: The main diagnostic distinction is between the kids who have a tic for a short amount of time and in whom it usually disappears around age 9 vs those with chronic tics. I think of it as more of a spectrum of tic disorders, with TD at the more severe end and typically, though not always, with more tics in general.

CCPR: How common is Tourette’s disorder?

Dr. Greenberg: The prevalence of TD is about 0.5%, and an additional 1%–2% of the population has chronic tic disorder, so it’s a pretty rare syndrome (Scharf JM et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51(2):192–201.e5). That said, about 15% of kids will have a tic at some point, but if it doesn’t last for a year, it doesn’t meet the criteria.

CCPR: As a doctor working in a tertiary academic center, your practice is going to be different from a typical child psychiatrist’s. How common is it for parents to bring in a child specifically for a tic problem?

Dr. Greenberg: For a typical child psychiatrist, the more likely scenario is that a parent will bring in a child with OCD or ADHD symptoms, and the clinician will notice some tics and ask questions, especially if he or she is aware of the Tourette’s disorder triad of tics, OCD, and ADHD.

CCPR: So, if we do see a kid with OCD, we should be thinking about tics.

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, definitely. About 15%–25% of kids with OCD will have tics, especially if the OCD is early onset, meaning prepubertal/early adolescence (Rizzo R et al, J Child Neurol 2014;29(10):1383–1389). In fact, early-onset OCD is genetically linked with TD. So, just in terms of the genetics, if a parent has TD, the child might have OCD or vice versa.

CCPR: And there’s also a connection between ADHD and tics?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes. Again, around 15%–20% of kids with ADHD will have tics, and about 60% or more of TD patients have ADHD (Bloch MH et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48(9):884–893). The point is, a lot of kids with ADHD will have tics; so, if you treat them with a stimulant and see tics, it’s not necessarily that the stimulant caused the tics—often, the tics might have developed anyway.

CCPR: Can you walk us through a typical evaluation?

Dr. Greenberg: Sure. I have 90-minute intake slots, and I see the kids and the parents together, then each separately, and then bring them together in the end. I usually start by asking about the typical features of tics. Do they come and go or “wax and wane”? Do they occur in bouts? Do they “jump” or change in location over time? Is it like an itch the child needs to scratch? Does talking about them make them worse? I do sometimes start with more open-ended questions, but sometimes asking the more specific questions helps to build rapport, because I’m validating a symptom. A lot of these kids will be told over and over, “Just stop that. Why are you doing that? That’s annoying; cut it out.” And they’ll say they can’t. Asking about tic features as legitimate symptoms builds immediate trust. From there, I typically ask about comorbidities.

Table: The Many Types of Tics

(Click here to view full-size PDF)

CCPR: How do you approach that?

Dr. Greenberg: I’ll start by saying, “A lot of kids I see who have tics often have other things going on. Some of them have a lot of difficulty with worrying or having to repeat certain things, or with mood or anger, or with paying attention. Do any of those sound familiar to you?” They might say yes or no. And then I’ll try to go syndrome by syndrome to determine if, given the fact that they have tics, they have any of the other common comorbidities. Since many parents have heard of it, I might just ask, “Have you heard of OCD? What do you know about it? Are there any OCD symptoms you think your child might have?” And, depending on their answer, I’ll then ask more pointed questions such as about excessive handwashing, checking, or confessing behaviors. And I’ll bring it up with the child again when we talk separately.

CCPR: So the separate interview is key to your evaluation?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes. Both sets of answers will help determine what to treat first. In the case of OCD, I’ll ask the child directly, “Do you feel like you have unwanted thoughts or urges that get stuck in your head that you just can’t get out? And if you do, do you feel like you need to do something or think something to get rid of it, or that if you don’t, you might worry something bad might happen?” The parents are not always aware of the child’s thinking in this respect. And often the parents and the kid will have different views of the problem. A parent may come in and say, “My kid is ticcing all the time. I worry that kids at school make fun of him. I tell him to stop.” Whereas, if you ask the kid, he will say, “Actually, the tics don’t really bother me. I told my friends it’s just something I do. What really bothers me is that I have these thoughts that I can’t get out of my head, or I’m really anxious or I can’t concentrate.”

CCPR: Are there any assessment tools that you use?

Dr. Greenberg: I tend to give parents a Vanderbilt form to fill out, which not only assesses ADHD symptoms but also disruptive behavior disorders that affect about 25% of kids with TD (available for download at http://www.nichq.org/childrens-health/adhd/resources/vanderbilt-assessment-scales). A good number of them have intermittent explosive disorder. Often these are the kids who will have a rage reaction that might last minutes to an hour, completely out of proportion to the trigger. Afterwards, they are extremely apologetic and feel really bad. These aren’t kids who are chronically irritable, purposely breaking things, getting in trouble; it’s almost like they lose themselves in their rage.

CCPR: How important is it to actually see the child ticcing during the evaluation?

Dr. Greenberg: A lot of kids can suppress tics in the doctor’s office or in school; that certainly does not mean they don’t have them. Kids with tics can hold them in for a while; it’s like holding back a sneeze or an itch.

CCPR: What other disorders do you screen for?

Dr. Greenberg: Anxiety disorders occur in about 30% in people with TD (Coffey B et al, Adv Neurol 1992;58:95–104), so in addition to asking about amount of worrying in the office, I like to give the SCARED (the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders), which can be helpful in parsing out generalized anxiety vs separation anxiety or other disorders (available for download at http://www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/content.asp?id=2333). I always make sure to do a full depression screen, including suicidality. This can get tricky in patients with OCD, because the patient might have aggressive obsessions, like “What if I kill myself?” or “What if I stab my mom?” I try to assess whether these are ego-dystonic, intrusive thoughts (and thus part of the child’s OCD) or if they are products of depression. It is even more complicated because those with TD and comorbid OCD tend to have increased rates of aggressive obsessions (in addition to increased symmetry, sexuality, and religiosity obsessions) compared to those without comorbid tics.

CCPR: What about the motor tics being potentially confused with self-harm movements? Is that an issue?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, and that too can be complicated. I have a number of kids who have tics that involve hitting themselves. This is due to some sort of internal “itch” or sensation that they feel is only relieved by doing this. If you ask them, they don’t want to be doing it. The word we often use is “unvoluntary”—it’s not quite involuntary, nor is it voluntary. But it’s difficult to suppress, and the bad feeling of suppressing it sometimes outweighs the feeling of slamming your hand to your chest. This is different from kids who have self-injurious behavior where the action is more deliberate and purposeful.

CCPR: TD is also famous for coprolalia (ie, swearing tics). Is that an important part of the diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg: While coprolalia probably is the most well-known symptom, actually that particular tic occurs in only about 15% of those with TD (Cohen S et al, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2013;37(6):997–1007. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.013). It’s informative if present, but not all that reliable in making the diagnosis. If you are looking for that symptom to make the diagnosis, you will miss a lot of kids!

CCPR: At what point do you actually feel like you’ve ascertained that a patient has Tourette’s disorder versus a tic disorder?

Dr. Greenberg: To make that distinction, I ask about the history over time. As long as it’s been at least a year, even if the tics come and go, and the child has had at least 2 motor tics—it could be eye blinking or shoulder shrugging—and at least 1 vocal tic, such as sniffing or throat clearing, then I would say that’s TD. A quick trick that can often be helpful is asking whether the patient is making the movement because of a thought or feeling (more OCD-like) or to relieve a bodily sensation (more tic-like). Oftentimes, kids with “Tourettic OCD” (meaning those who have OCD with tics) will describe feelings of incompleteness and need to do a compulsion until things feel “just right.” These are called “Not Just Right Experience” obsessions/compulsions, or NJREs for short.

CCPR: Is there a particular age group you tend to see?

Dr. Greenberg: Many times it’s 10-year-olds, because that’s about the age when the tics tend to escalate in frequency and intensity. But, if you ask the child or parents to think back—“Do you remember anything like this when they were 4 or 5?”—the parent might say, “Maybe,” and the kid might say, “Yeah, I used to blink a lot.” So a lot of times the tics have been there for a while; they just didn’t cause any problems, or parents thought they were secondary to a cold and missed them as a symptom.

CCPR: So this remains a clinical diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, the main way to diagnose TD and all tic disorders is through a good, thorough history. You don’t really need to do any other labs or tests, unless you elicit signs and symptoms that are unexpected, such as an abnormal neurological exam. What’s also important in tics is that the child is making the movement as opposed to hemiballismus or other movement disorders such as chorea or Parkinson movements, where the body is sort of doing it without the brain. The child is the one in charge of tics: Kids (often) know they are ticcing; it’s just that they have trouble stopping. Another really helpful tenet about tics in making a TD diagnosis is their history. Classically, tics tend to occur: 1) motor before vocal; 2) simple before complex; 3) head/neck/shoulders and outwards. It would be rare to see someone with only a complex vocal tic who never had a history of eye blinking or shoulder shrugging.

CCPR: As an expert, you have a pretty rich vocabulary for asking about all the different ways kids are ticcing, whereas clinicians with less experience might not. Can you share some of the distinctions you make?

Dr. Greenberg: Definitely. The accompanying table separates tics into motor and phonic as well as simple and complex. Of course, kids may have plenty of different tics, but if I ask about one that is recurrent and consistent, the kid should be able to demonstrate the moment voluntarily. Most kids around 10 years old can identify what’s called a “premonitory urge”; that’s the sensation they feel in their body before they tic, that the tic is typically trying to relieve. So, around that age, they may say, “I have this feeling that I can’t get rid of unless I do the movement.” Younger kids often will say, “I don’t know why I’m doing it; I just have to.”

CCPR: I imagine where it gets tricky is in making the comorbid diagnoses.

Dr. Greenberg: Yes, that’s generally where I end up focusing much of my interview, because what you don’t know, for instance, is whether the kids are so distractible simply because they are ticcing all the time. Are they anxious because the tics are preventing them from concentrating and causing them to do badly in class, or is their anxiety separate and co-occurring with and possibly exacerbating the tics?

CCPR: Those distinctions are important but often harder to clarify.

Dr. Greenberg: Correct. And, because these are kids, the comorbid disorders develop over time, so you might not have hit the period where you would necessarily see the other symptoms yet. As an example, OCD tends to maximize in severity about 2 years after tics maximize in their severity. So you just might not be in the period where they are experiencing the symptoms yet, or there might be little signs of it, but you don’t know. Or maybe they’re having a reactive, adjustment-based depression as opposed to a more innate, genetic depression. Those are the situations where I feel less comfortable making definitive diagnoses at the first appointment.

CCPR: Any closing advice?

Dr. Greenberg: The numbers vary, but about 60%–80% of kids will grow out of their tics, especially by their twenties. So, in general, clinicians can be pretty reassuring to parents. The more severe the tics are at younger ages, the less chance a person will grow out of it, but it’s not a perfect correlation. So it’s one of those disorders for which you can offer some sort of hope that eventually symptoms will lessen or even go away completely.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Greenberg.

Issue Date: March 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)