Home » Treating Tourette’s Disorder

Treating Tourette’s Disorder

March 1, 2017

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Melissa Fluehr

Clinical research coordinator, Behavioral Science Unit, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Ms. Fluehr has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Maxwell Luber

Clinical research coordinator, Behavioral Science Unit, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Mr. Luber has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Barbara Coffey, MD, MS

Director, National Tourette Center of Excellence, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Dr. Coffey has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

David was a 12-year-old boy referred for consultation by his child psychiatrist for help in managing his severe Tourette’s disorder. David had developed onset of eye blinking at age 6 in the context of problems paying attention in his first-grade classroom. He tended to call out answers and wasn’t completing tests or his homework. By age 8, he had developed head and neck jerks, was making guttural sounds, and eventually began screaming. Most recently, he had begun to bang his head into the wall, explode in outbursts, arch his neck, and writhe on the floor and punch himself. David’s parents reported that he had also begun to experience obsessions and compulsions in the past year. David had prohibitions about touching certain things, and his belongings had to be “just right.” Hearing his mother’s voice was a trigger for his outbursts. He became stuck on things easily and had many “requirements,” such as that his left foot always be put in front of his right foot while walking.

Introduction to Tourette’s disorder

Tourette’s disorder (TD), also known as Tourette syndrome, is a fascinating yet complex neurodevelopmental disorder that can be challenging to treat. Dr. Georges Gilles de la Tourette, a French neurologist who described the first nine cases in 1885, had it right when he described the “peculiar” symptoms as a syndrome, later reporting that “fears, phobias, and arithmomania” were part of the picture (American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013). These observations set the stage for our current understanding that, indeed, the vast majority of patients with TD also have non-tic symptoms. These include symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), as described in David’s case, but also depression and explosive outbursts (Hirschtritt ME et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(4):325–333). In addition, body-focused repetitive behaviors, such as hair pulling and skin picking, are common in patients with TD—and you should ask specifically about these symptoms to avoid missing them.

Biological mechanisms

The cause of TD remains unknown despite an acceleration of scientific investigation in the past two decades. Although clearly a familial disorder, no genetic markers achieved significance in a recent large genetic study (Scharf JM et al, Mol Psychiatry 2013;18(6):721–728). Most investigations point to disinhibition/dysregulation of the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CTSC) pathways, characterized by hyper-functioning of dopamine circuits. Evidence for dopamine dysfunction is supported by the fact that antipsychotic medications, which block dopamine transmission, are effective in suppressing tics and were the first medications reported to be beneficial in TD (Robertson MM, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2012;97(5):166–175).

Evaluation

The first step in your evaluation is to come up with a problem list of target symptoms for treatment. It is important to ask the parents and child what is most problematic and, of course, to obtain collateral information from teachers, other caregivers, and other clinicians familiar with the child. The next step is to prioritize the problem list based on which symptoms are causing the most distress or impairment. Often, parents, especially those of very young children, are more troubled by tics than the child is. You should make sure to review the child’s specific and typical course of tics over time, as they often fluctuate and change in type, location, and intensity. That way, there are fewer surprises if tics seem to increase after starting treatment, since this may reflect a fluctuation rather than true worsening.

The initial evaluation is also a good time to discuss with the family what we know about the course of tics, ADHD, and OCD, since better understanding of what is likely to come can help everyone make the most informed treatment decision. It is fairly well established that tics usually peak before puberty and attenuate in mid to late adolescence. However, OCD symptoms tend to persist and at times increase in intensity just as tics are diminishing (Bloch et al, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(1):65–99). ADHD is, for the most part, likely to persist into adulthood and, among the “Tourette’s disorder triad” of tics, OCD, and ADHD, is the disorder most likely to be associated with longer-term impairment. Thus, while it might be reasonable to monitor and simply “watch and wait” for tics to improve over time, OCD, ADHD, and mood and anxiety symptoms usually need treatment.

Treatment of comorbid disorders

There have been no controlled studies to date on how treating comorbid psychiatric symptoms impacts tic severity and course. I’ve often found that treatment of distressful or impairing behavioral and emotional symptoms as well as reducing external stressors and sleep problems results in a happier and more well-adjusted child, which in turn may lead to a reduction in the frequency and severity of tics. It is a well-known phenomenon that anxiety and stress are apt to increase tics, so this may be a mechanism to explain why children usually feel better when they are able to fully pay attention and/or worry less.

When ADHD is the primary problem, I’m likely to recommend stimulant treatment. You might be concerned that adding a stimulant will worsen tics, but a recent meta-analysis of more than 2,000 youth with ADHD treated with stimulants reported that the rate of new onset or exacerbation of tics was about 6% for both stimulants and placebo (Cohen S et al, J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(9):728–773). Age, type of stimulant, and duration of treatment did not matter. Weighed in the balance, the child is often better off receiving effective treatment of ADHD early on to ward off potential long-term poor outcomes, even if tics increase a bit on a stimulant. To minimize tics, start by prescribing a low dose of an immediate-release methylphenidate and slowly titrating upward, then switch to an equivalent dose of a longer-acting formulation. If tics do worsen on stimulants, you can try an alpha-adrenergic agonist like guanfacine. Another option is to switch to atomoxetine, which was effective and well tolerated in a randomized controlled trial in children with ADHD and tics; in fact, in this study, tics in the children with TD actually improved (Allen AJ et al, Neurology 2005;65(12):1941–1949).

When treating OCD, try to distinguish complex motor tics from compulsions. This can be challenging at times. For example, when a child must touch all the corners on a table in a certain way, it may seem obvious that this is a compulsion—but it could be a complex motor tic. To sort this out, ask your patient what type of feeling, thought, or urge precedes the repetitive behavior. Tics tend to be preceded by an urge or sensation, whereas compulsions are triggered by a thought or worry. If it appears that the behavior is an OCD symptom, a trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is the best way to go.

If your patient has a concurrent mood or anxiety disorder, approach treatment as you would for any child with such symptoms. Unfortunately, there are few data to support specific medications or strategies for treatment of these symptoms in children with TD.

Treatment of tics

It is important to remember that not all tics need to be treated. We recommend treatment of tics only when they are causing significant distress or interfering with the child’s daily functioning in school, at home, or with friends. Since tics tend to peak between about ages 9 to 12 years and lessen in mid to late adolescence, some children need only monitoring, support, and advice to live their lives to the fullest during this crucial developmental period.

Behavioral treatment

If tics do need treatment and are mild to moderate in severity, which is the case for the vast majority of children with TD, my recommendation is to start a behavioral intervention. One especially effective approach is to use a manualized treatment called the Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT). (You can download a brochure on CBIT from the Tourette Association here: https://www.tourette.org/media/TAACBITenglish101316final.pdf.) The therapist starts by teaching the child to be aware of the urges or sensations that precede the tic. Then, the treater and patient come up with a competing response that is incompatible with the behavior. For example, if the patient has a throat clearing tic, doing deep breathing might interfere with that tic. Most children and parents like this approach, since it supports the child’s autonomy, helps promote a sense of competence, and has no adverse effects (except perhaps family conflict arising from the need to practice the competing responses between appointments!).

Medication treatment

For children whose tics are moderate to severe or who have failed behavioral treatment, medication is indicated. My first-line recommendation is an alpha-adrenergic agonist. I usually start with guanfacine, which typically is better tolerated and longer-acting than clonidine. Doses are low, as indicated in the accompanying table, especially for a prepubertal child. A typical total dose for school-age children is 1.5 mg–3 mg a day and up to 4 mg a day for adolescents, many of whom can tolerate somewhat faster titration. Clonidine is similar, but the starting dose is 0.025 mg and sedation often is more of a rate-limiting factor. Because of potential cardiovascular effects, a baseline EKG with repeat at the optimal dose is recommended.

Currently, there are three FDA-approved antipsychotics for treatment of TD: haloperidol, pimozide, and most recently aripiprazole. These are my go-to choices when the child has failed an alpha agonist. Of these, my recommendation is to start with aripiprazole, which may have the best balance of efficacy and risks. See the accompanying table for dose ranges and titration recommendations. For example, for a prepubertal child, the usual target dose is 4 mg–5 mg a day; this number is higher for latency-age children and higher yet for adolescents.

If the child’s tics are very severe, you can combine an alpha agonist with an antipsychotic, but keep in mind that more adverse effects are likely. I also use several other less-well-known medications, including topiramate, baclofen, and fluphenazine, for which there is a small body of literature (Jankovic J et al, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81(1):70–73).

Non-medication approaches that have been used in treatment-resistant adults such as botulinum toxin injections, transcranial magnetic stimulation, or deep brain stimulation are generally not recommended in youth.

CCPR Verdict: With tic disorders, comorbid problems are common; when treating tics, start with behavioral therapy, then alpha agonists and antipsychotics if needed.

Child PsychiatryIntroduction to Tourette’s disorder

Tourette’s disorder (TD), also known as Tourette syndrome, is a fascinating yet complex neurodevelopmental disorder that can be challenging to treat. Dr. Georges Gilles de la Tourette, a French neurologist who described the first nine cases in 1885, had it right when he described the “peculiar” symptoms as a syndrome, later reporting that “fears, phobias, and arithmomania” were part of the picture (American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013). These observations set the stage for our current understanding that, indeed, the vast majority of patients with TD also have non-tic symptoms. These include symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), as described in David’s case, but also depression and explosive outbursts (Hirschtritt ME et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(4):325–333). In addition, body-focused repetitive behaviors, such as hair pulling and skin picking, are common in patients with TD—and you should ask specifically about these symptoms to avoid missing them.

Biological mechanisms

The cause of TD remains unknown despite an acceleration of scientific investigation in the past two decades. Although clearly a familial disorder, no genetic markers achieved significance in a recent large genetic study (Scharf JM et al, Mol Psychiatry 2013;18(6):721–728). Most investigations point to disinhibition/dysregulation of the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CTSC) pathways, characterized by hyper-functioning of dopamine circuits. Evidence for dopamine dysfunction is supported by the fact that antipsychotic medications, which block dopamine transmission, are effective in suppressing tics and were the first medications reported to be beneficial in TD (Robertson MM, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2012;97(5):166–175).

Evaluation

The first step in your evaluation is to come up with a problem list of target symptoms for treatment. It is important to ask the parents and child what is most problematic and, of course, to obtain collateral information from teachers, other caregivers, and other clinicians familiar with the child. The next step is to prioritize the problem list based on which symptoms are causing the most distress or impairment. Often, parents, especially those of very young children, are more troubled by tics than the child is. You should make sure to review the child’s specific and typical course of tics over time, as they often fluctuate and change in type, location, and intensity. That way, there are fewer surprises if tics seem to increase after starting treatment, since this may reflect a fluctuation rather than true worsening.

The initial evaluation is also a good time to discuss with the family what we know about the course of tics, ADHD, and OCD, since better understanding of what is likely to come can help everyone make the most informed treatment decision. It is fairly well established that tics usually peak before puberty and attenuate in mid to late adolescence. However, OCD symptoms tend to persist and at times increase in intensity just as tics are diminishing (Bloch et al, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(1):65–99). ADHD is, for the most part, likely to persist into adulthood and, among the “Tourette’s disorder triad” of tics, OCD, and ADHD, is the disorder most likely to be associated with longer-term impairment. Thus, while it might be reasonable to monitor and simply “watch and wait” for tics to improve over time, OCD, ADHD, and mood and anxiety symptoms usually need treatment.

Treatment of comorbid disorders

There have been no controlled studies to date on how treating comorbid psychiatric symptoms impacts tic severity and course. I’ve often found that treatment of distressful or impairing behavioral and emotional symptoms as well as reducing external stressors and sleep problems results in a happier and more well-adjusted child, which in turn may lead to a reduction in the frequency and severity of tics. It is a well-known phenomenon that anxiety and stress are apt to increase tics, so this may be a mechanism to explain why children usually feel better when they are able to fully pay attention and/or worry less.

When ADHD is the primary problem, I’m likely to recommend stimulant treatment. You might be concerned that adding a stimulant will worsen tics, but a recent meta-analysis of more than 2,000 youth with ADHD treated with stimulants reported that the rate of new onset or exacerbation of tics was about 6% for both stimulants and placebo (Cohen S et al, J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(9):728–773). Age, type of stimulant, and duration of treatment did not matter. Weighed in the balance, the child is often better off receiving effective treatment of ADHD early on to ward off potential long-term poor outcomes, even if tics increase a bit on a stimulant. To minimize tics, start by prescribing a low dose of an immediate-release methylphenidate and slowly titrating upward, then switch to an equivalent dose of a longer-acting formulation. If tics do worsen on stimulants, you can try an alpha-adrenergic agonist like guanfacine. Another option is to switch to atomoxetine, which was effective and well tolerated in a randomized controlled trial in children with ADHD and tics; in fact, in this study, tics in the children with TD actually improved (Allen AJ et al, Neurology 2005;65(12):1941–1949).

When treating OCD, try to distinguish complex motor tics from compulsions. This can be challenging at times. For example, when a child must touch all the corners on a table in a certain way, it may seem obvious that this is a compulsion—but it could be a complex motor tic. To sort this out, ask your patient what type of feeling, thought, or urge precedes the repetitive behavior. Tics tend to be preceded by an urge or sensation, whereas compulsions are triggered by a thought or worry. If it appears that the behavior is an OCD symptom, a trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is the best way to go.

If your patient has a concurrent mood or anxiety disorder, approach treatment as you would for any child with such symptoms. Unfortunately, there are few data to support specific medications or strategies for treatment of these symptoms in children with TD.

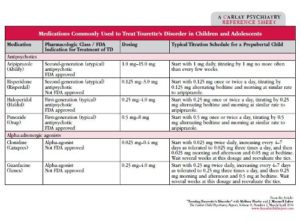

Table: Medications Commonly Used to Treat Tourette’s Disorder in Children and Adolescents

(Click here to view full-size PDF)

Treatment of tics

It is important to remember that not all tics need to be treated. We recommend treatment of tics only when they are causing significant distress or interfering with the child’s daily functioning in school, at home, or with friends. Since tics tend to peak between about ages 9 to 12 years and lessen in mid to late adolescence, some children need only monitoring, support, and advice to live their lives to the fullest during this crucial developmental period.

Behavioral treatment

If tics do need treatment and are mild to moderate in severity, which is the case for the vast majority of children with TD, my recommendation is to start a behavioral intervention. One especially effective approach is to use a manualized treatment called the Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT). (You can download a brochure on CBIT from the Tourette Association here: https://www.tourette.org/media/TAACBITenglish101316final.pdf.) The therapist starts by teaching the child to be aware of the urges or sensations that precede the tic. Then, the treater and patient come up with a competing response that is incompatible with the behavior. For example, if the patient has a throat clearing tic, doing deep breathing might interfere with that tic. Most children and parents like this approach, since it supports the child’s autonomy, helps promote a sense of competence, and has no adverse effects (except perhaps family conflict arising from the need to practice the competing responses between appointments!).

Medication treatment

For children whose tics are moderate to severe or who have failed behavioral treatment, medication is indicated. My first-line recommendation is an alpha-adrenergic agonist. I usually start with guanfacine, which typically is better tolerated and longer-acting than clonidine. Doses are low, as indicated in the accompanying table, especially for a prepubertal child. A typical total dose for school-age children is 1.5 mg–3 mg a day and up to 4 mg a day for adolescents, many of whom can tolerate somewhat faster titration. Clonidine is similar, but the starting dose is 0.025 mg and sedation often is more of a rate-limiting factor. Because of potential cardiovascular effects, a baseline EKG with repeat at the optimal dose is recommended.

Currently, there are three FDA-approved antipsychotics for treatment of TD: haloperidol, pimozide, and most recently aripiprazole. These are my go-to choices when the child has failed an alpha agonist. Of these, my recommendation is to start with aripiprazole, which may have the best balance of efficacy and risks. See the accompanying table for dose ranges and titration recommendations. For example, for a prepubertal child, the usual target dose is 4 mg–5 mg a day; this number is higher for latency-age children and higher yet for adolescents.

If the child’s tics are very severe, you can combine an alpha agonist with an antipsychotic, but keep in mind that more adverse effects are likely. I also use several other less-well-known medications, including topiramate, baclofen, and fluphenazine, for which there is a small body of literature (Jankovic J et al, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81(1):70–73).

Non-medication approaches that have been used in treatment-resistant adults such as botulinum toxin injections, transcranial magnetic stimulation, or deep brain stimulation are generally not recommended in youth.

CCPR Verdict: With tic disorders, comorbid problems are common; when treating tics, start with behavioral therapy, then alpha agonists and antipsychotics if needed.

Issue Date: March 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)