Home » Beginning Antidepressant Treatment: A Recommended Approach

Beginning Antidepressant Treatment: A Recommended Approach

July 1, 2017

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Michael Posternak, MD

Psychiatrist in private practice in Boston, MA

Dr. Posternak has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

How do you start a new patient on antidepressant treatment? We do this countless times in our practices, and reviewing the topic may feel a bit like returning to residency. However, it’s important to revisit our standard operating procedures from time to time to ensure we’re thinking carefully about our decisions during our busy days.

If we turn to our treatment guidelines, we find little to direct us. For example, the American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder says:

For most patients, the effectiveness of antidepressant medications is generally comparable between classes and within classes of medications. Therefore, the initial selection of an antidepressant medication will largely be based on the tolerability, safety, and cost of the medication, as well as patient preference and history of prior medication treatment (Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010, p. 31).

In the absence of authoritative guidelines, we all develop our own algorithms for deciding on antidepressants. Here are mine.

My first assumption, like the APA’s, is that all antidepressants have roughly equal effectiveness, on average. True, there are arguably a few minor exceptions to this rule: 1. TCAs may be more effective than SSRIs for severe or melancholic depression (Anderson IM, Depress Anxiety 1998;7 Suppl 111–117); 2. MAOIs may be more effective than other antidepressants for atypical depression (Quitkin F et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:749–760); and 3. Dual reuptake inhibitors (eg, venlafaxine, duloxetine) may be slightly more effective than SSRIs (Bauer M et al, Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;259(3):172–185). Yet even these putative advantages are debatable, and if they are real, they are modest at best.

Assuming that all antidepressants are equally effective, I use a series of factors other than efficacy to choose. These factors are grouped into the following categories:

Symptom profiling

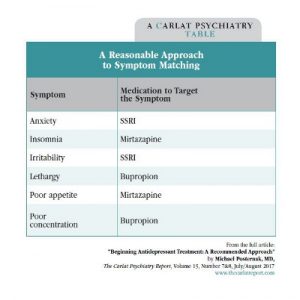

Matching antidepressants to a symptom profile is more art than science, since few studies have attempted to determine whether this method can improve outcomes. Nonetheless, most of us do symptom matching, and many readers will recognize the logic of this approach based on this table.

Psychiatric comorbidities

The presence of psychiatric comorbidities often tips the balance for selecting antidepressants, and when it does it will almost always be in the same direction: toward SSRIs. SSRIs are efficacious for nearly every anxiety disorder (panic disorder, GAD, social anxiety disorder, OCD, and PTSD), as well as other diagnoses, including eating disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder (or anger and irritability in its less severe form).

Several other antidepressants are “twofers” or “threefers.” Wellbutrin helps with smoking cessation and can treat ADHD symptoms in addition to depression. Cymbalta has been FDA-approved for various pain conditions, including fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and diabetic neuropathy. Tricyclic antidepressants can also help with these pain syndromes as well as migraines.

History of medication response

While there is very little research to support the common practice of using a history of prior drug response to help make decisions, the following guidelines are reasonable and are at least not contradicted by any published findings:

If a patient reports that a close family member responded well to a particular antidepressant, does that suggest the patient is more likely to respond to it? I have only been able to locate a single study that has attempted to address this question. In a small case series, Pare and Mack found that family history of response was predictive of response in patients when comparing TCAs versus MAOIs—the only two antidepressant classes that existed when the study was published (Pare CM and Mack JW, J Med Genet 1971; 8(3):306–309). Obviously, much more research is needed in this area.

Side effects

While the list of potential side effects to antidepressants is seemingly infinite, the two that are of primary concern to patients are weight gain and sexual side effects (Zimmerman M et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(5):603–610). Of the first-line agents, only paroxetine and mirtazapine are likely to cause significant weight gain. All other antidepressants may be considered weight-neutral. All serotonergic agents (SSRIs, SNRIs, Trintellix, Viibryd), as well as TCAs and MAOIs, are associated with sexual side effects.

Miscellaneous risks and drawbacks

Because there are so many antidepressant options to choose from, any clear disadvantage in a medication basically eliminates it from first-line consideration. Below is a list of six commonly encountered drawbacks:

My five go-to antidepressants

At this point, my first-line antidepressant list has been whittled down to five medications: three SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram), bupropion, and mirtazapine (when weight gain is not a major concern). Here are my reasons for including each of these in my exclusive go-to list:

Trial duration

It had long been held that antidepressants needed 2 weeks to start working, and that patients who responded sooner were believed to be mostly placebo responders. Recent studies have largely debunked the antidepressant-delay theory; it is common for patients to begin feeling the initial positive effects within the first week of treatment (Posternak MA and Zimmerman M, J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(2):148–155).

How long should you keep your patient on an antidepressant? Studies that have tracked response rates week by week provide some useful data. Among patients who have shown no improvement after 4 weeks on an antidepressant, about 15% will respond if kept on meds for 2 more weeks. And after 6 weeks of no response, 10% will respond with an additional 2 weeks of treatment (Posternak MA et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72(7):949–954).

The bottom line is that we still don’t know the optimal duration for antidepressant trials. Four to 6 weeks seems like a reasonable guideline, but a surprising number of patients do respond if you keep them on their antidepressant for a bit longer (ie, 8–10 weeks).

Antidepressant dosing

The package inserts for antidepressants list both a recommended starting dose and a maximum dosage. Most clinicians will typically increase the dosage after a few weeks of no response, theorizing that the higher the dosage, the more likely the response. Is this a rational way to practice? It’s debatable, but studies with fixed dosage design provide some guidance. In a fixed-dosage trial, subjects are randomized to a low, medium, or high dosage of their antidepressant medication from the beginning of treatment. For example, in one representative study, 369 depressed patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups: sertraline 50 mg (n = 95), sertraline 100 mg (n = 92), sertraline 200 mg (n = 91), or placebo (n = 91), over the course of 6 weeks. The combined response rate for the three sertraline cohorts was 60.1%, compared to only 42.1% for those receiving placebo. But when we break down response by cohort, we see that dosage had no effect: Response rates in the sertraline 50 mg, 100 mg, and 200 mg cohorts were 58.5%, 62.7%, and 58.9%, respectively (Fabre LF et al, Biol Psychiatry;38(9):592–602). This is the same pattern we find in most—though not all—fixed-dosage studies. (Venlafaxine, tricyclics, and MAOIs are exceptions, in that increasing dosages are correlated with greater response.)

Notwithstanding this lack of good support for increasing the dosage, I do generally increase doses after non-response. Why? At the 2- to 3-week follow-up visit, if there has been no improvement, patients may start to become discouraged. You can always advise them to stay the course with the current dosage, but some patients will push back, and you don’t want them to lose so much confidence in the treatment that they stop taking their meds. Increasing the dosage at this point keeps patients in treatment and keeps them on at least the same dosage as they started. If they improve over the next few weeks, you will have no idea if they are getting better because of the higher dosage or simply the passage of time—but they are getting better, which is the important thing.

In practice, here is how I dose antidepressants (see table above). First, I start with half the minimum effective dosage (eg, sertraline 25 mg, fluoxetine 10 mg, etc). Assuming the patient is tolerating the medication, I then increase the dosage after 1 week to the minimum effective dosage (eg, sertraline 50 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg, etc). I typically will see patients back for their first follow-up visit 2–3 weeks after they start the medication. If there has been no improvement, I will increase the dosage, and I will then see them again at the 6-week mark. If they still have not improved, I’ll consider other options, such as switching or augmentation.

TCPR Verdict: When starting antidepressants, choose from a short list of “go-tos” and encourage patients to stay the course for 6–12 weeks. Increasing the dosage is recommended, but usually not necessary.

General PsychiatryIf we turn to our treatment guidelines, we find little to direct us. For example, the American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder says:

For most patients, the effectiveness of antidepressant medications is generally comparable between classes and within classes of medications. Therefore, the initial selection of an antidepressant medication will largely be based on the tolerability, safety, and cost of the medication, as well as patient preference and history of prior medication treatment (Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010, p. 31).

In the absence of authoritative guidelines, we all develop our own algorithms for deciding on antidepressants. Here are mine.

My first assumption, like the APA’s, is that all antidepressants have roughly equal effectiveness, on average. True, there are arguably a few minor exceptions to this rule: 1. TCAs may be more effective than SSRIs for severe or melancholic depression (Anderson IM, Depress Anxiety 1998;7 Suppl 111–117); 2. MAOIs may be more effective than other antidepressants for atypical depression (Quitkin F et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:749–760); and 3. Dual reuptake inhibitors (eg, venlafaxine, duloxetine) may be slightly more effective than SSRIs (Bauer M et al, Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;259(3):172–185). Yet even these putative advantages are debatable, and if they are real, they are modest at best.

Assuming that all antidepressants are equally effective, I use a series of factors other than efficacy to choose. These factors are grouped into the following categories:

- Symptom profile

- Psychiatric comorbidities

- Antidepressant treatment history

- Side effect profiles

- Other risks and drawbacks

Symptom profiling

Matching antidepressants to a symptom profile is more art than science, since few studies have attempted to determine whether this method can improve outcomes. Nonetheless, most of us do symptom matching, and many readers will recognize the logic of this approach based on this table.

A Reasonable Approach to Symptom Matching

(Click here to view as a full-size PDF.)

Psychiatric comorbidities

The presence of psychiatric comorbidities often tips the balance for selecting antidepressants, and when it does it will almost always be in the same direction: toward SSRIs. SSRIs are efficacious for nearly every anxiety disorder (panic disorder, GAD, social anxiety disorder, OCD, and PTSD), as well as other diagnoses, including eating disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder (or anger and irritability in its less severe form).

Several other antidepressants are “twofers” or “threefers.” Wellbutrin helps with smoking cessation and can treat ADHD symptoms in addition to depression. Cymbalta has been FDA-approved for various pain conditions, including fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and diabetic neuropathy. Tricyclic antidepressants can also help with these pain syndromes as well as migraines.

History of medication response

While there is very little research to support the common practice of using a history of prior drug response to help make decisions, the following guidelines are reasonable and are at least not contradicted by any published findings:

- If the patient clearly responded to an antidepressant in the past, try it again.

- If the patient responded in the past but developed intolerable side effects, consider a re-challenge. Side effects often do not recur, or they can be mitigated if precautionary steps are taken (eg, slower titration of dosage). Alternatively, if possible, try another antidepressant from the same class.

- If the patient tried but did not respond to a particular antidepressant in the past, most clinicians probably would never reuse that antidepressant. But occasionally I do, because the depression the patient is experiencing today may be fundamentally different from the one the patient experienced many years ago. In the words of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, “You can never step in the same river twice.”

If a patient reports that a close family member responded well to a particular antidepressant, does that suggest the patient is more likely to respond to it? I have only been able to locate a single study that has attempted to address this question. In a small case series, Pare and Mack found that family history of response was predictive of response in patients when comparing TCAs versus MAOIs—the only two antidepressant classes that existed when the study was published (Pare CM and Mack JW, J Med Genet 1971; 8(3):306–309). Obviously, much more research is needed in this area.

Side effects

While the list of potential side effects to antidepressants is seemingly infinite, the two that are of primary concern to patients are weight gain and sexual side effects (Zimmerman M et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(5):603–610). Of the first-line agents, only paroxetine and mirtazapine are likely to cause significant weight gain. All other antidepressants may be considered weight-neutral. All serotonergic agents (SSRIs, SNRIs, Trintellix, Viibryd), as well as TCAs and MAOIs, are associated with sexual side effects.

Miscellaneous risks and drawbacks

Because there are so many antidepressant options to choose from, any clear disadvantage in a medication basically eliminates it from first-line consideration. Below is a list of six commonly encountered drawbacks:

- Lethality in overdose. Although most antidepressants are potentially lethal when taken at high enough doses, tricyclic antidepressants pose by far the greatest risk in this regard. Therefore, they should almost always be reserved as second- or third-line agents.

- Drug interactions. There are countless potential drug interactions, and it is impossible to keep all of them in mind. Fortunately, drug interactions are only relevant in the subset of patients with treated medical comorbidities. In these instances, MAOIs, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine, plus fluoxetine to a lesser extent, have the greatest potential for problematic drug interactions.

- High “nuisance factor.” MAOIs require dietary restrictions, while TCAs require blood levels and EKGs in patients over 40. For these and other reasons, they should be avoided as first-line agents.

- Cardiac concerns. TCAs and citalopram (at least at dosages greater than 40 mg) both may prolong the QT interval, and EKGs are recommended. The degree of risk, particularly with citalopram, is debatable (Ray WA et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78(2):190–195. doi:10.4088/JCP.15m10324), but with so many other options, there is little justification for incurring this risk.

- Lack of track record. Although patients frequently ask whether there are any new and exciting antidepressants on the market, I generally wait a few years before test-driving new drugs—unless they represent obvious advances in efficacy.

- Discontinuation syndrome. Five antidepressants stand out as the worst offenders in terms of discontinuation syndrome and therefore should rarely be first-line agents: venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine.

My five go-to antidepressants

At this point, my first-line antidepressant list has been whittled down to five medications: three SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram), bupropion, and mirtazapine (when weight gain is not a major concern). Here are my reasons for including each of these in my exclusive go-to list:

- I consider the three SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram) largely indistinguishable, and therefore the choice between them will be somewhat arbitrary. SSRIs provide the broadest array of potential benefits, have few drug interactions, are safe in overdose, and are well tolerated apart from sexual side effects.

- Bupropion has arguably the best side effect profile of all the antidepressants, as it is devoid of both sexual side effects and weight gain potential. It has few drug interactions, carries no cardiac or GI concerns, and is probably the most energizing of the antidepressants. It is contraindicated only in patients who have a history of seizures.

- Mirtazapine is often the perfect choice for depressed patients with insomnia and decreased appetite. Weight gain and oversedation are its main drawbacks, but these may or may not occur, and they can often be mitigated by dosing adjustments (ie, lowering to 7.5 mg or even 3.375 mg) or taking the medication early in the evening if morning grogginess is a problem. In some patients, increasing the dose from 15 mg to 30 mg may paradoxically decrease sedation, because mirtazapine’s noradrenergic properties kick in at higher doses.

Trial duration

It had long been held that antidepressants needed 2 weeks to start working, and that patients who responded sooner were believed to be mostly placebo responders. Recent studies have largely debunked the antidepressant-delay theory; it is common for patients to begin feeling the initial positive effects within the first week of treatment (Posternak MA and Zimmerman M, J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(2):148–155).

How long should you keep your patient on an antidepressant? Studies that have tracked response rates week by week provide some useful data. Among patients who have shown no improvement after 4 weeks on an antidepressant, about 15% will respond if kept on meds for 2 more weeks. And after 6 weeks of no response, 10% will respond with an additional 2 weeks of treatment (Posternak MA et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72(7):949–954).

The bottom line is that we still don’t know the optimal duration for antidepressant trials. Four to 6 weeks seems like a reasonable guideline, but a surprising number of patients do respond if you keep them on their antidepressant for a bit longer (ie, 8–10 weeks).

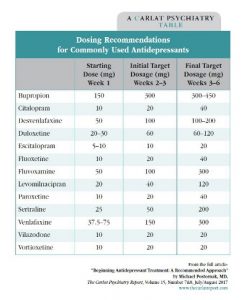

Antidepressant dosing

The package inserts for antidepressants list both a recommended starting dose and a maximum dosage. Most clinicians will typically increase the dosage after a few weeks of no response, theorizing that the higher the dosage, the more likely the response. Is this a rational way to practice? It’s debatable, but studies with fixed dosage design provide some guidance. In a fixed-dosage trial, subjects are randomized to a low, medium, or high dosage of their antidepressant medication from the beginning of treatment. For example, in one representative study, 369 depressed patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups: sertraline 50 mg (n = 95), sertraline 100 mg (n = 92), sertraline 200 mg (n = 91), or placebo (n = 91), over the course of 6 weeks. The combined response rate for the three sertraline cohorts was 60.1%, compared to only 42.1% for those receiving placebo. But when we break down response by cohort, we see that dosage had no effect: Response rates in the sertraline 50 mg, 100 mg, and 200 mg cohorts were 58.5%, 62.7%, and 58.9%, respectively (Fabre LF et al, Biol Psychiatry;38(9):592–602). This is the same pattern we find in most—though not all—fixed-dosage studies. (Venlafaxine, tricyclics, and MAOIs are exceptions, in that increasing dosages are correlated with greater response.)

Notwithstanding this lack of good support for increasing the dosage, I do generally increase doses after non-response. Why? At the 2- to 3-week follow-up visit, if there has been no improvement, patients may start to become discouraged. You can always advise them to stay the course with the current dosage, but some patients will push back, and you don’t want them to lose so much confidence in the treatment that they stop taking their meds. Increasing the dosage at this point keeps patients in treatment and keeps them on at least the same dosage as they started. If they improve over the next few weeks, you will have no idea if they are getting better because of the higher dosage or simply the passage of time—but they are getting better, which is the important thing.

In practice, here is how I dose antidepressants (see table above). First, I start with half the minimum effective dosage (eg, sertraline 25 mg, fluoxetine 10 mg, etc). Assuming the patient is tolerating the medication, I then increase the dosage after 1 week to the minimum effective dosage (eg, sertraline 50 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg, etc). I typically will see patients back for their first follow-up visit 2–3 weeks after they start the medication. If there has been no improvement, I will increase the dosage, and I will then see them again at the 6-week mark. If they still have not improved, I’ll consider other options, such as switching or augmentation.

Dosing Recommendations for Commonly Used Antidepressants

(Click here to view as a full-size PDF.)

TCPR Verdict: When starting antidepressants, choose from a short list of “go-tos” and encourage patients to stay the course for 6–12 weeks. Increasing the dosage is recommended, but usually not necessary.

Issue Date: July 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)