Home » When First-Line Depression Treatments Don’t Cut It: Newer Antidepressants and Sometimes, Antipsychotics

When First-Line Depression Treatments Don’t Cut It: Newer Antidepressants and Sometimes, Antipsychotics

July 1, 2017

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Michael Gitlin, MD

Director of the Outpatient Mood Disorder Program at UCLA, as well as author of The Psychotherapist’s Guide to Psychopharmacology (Free Press)

Dr. Gitlin has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Michael Gitlin, MD

Director of the Outpatient Mood Disorder Program at UCLA, as well as author of The Psychotherapist’s Guide to Psychopharmacology (Free Press)

Dr. Gitlin has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: It’s been about 10 years since we last talked with you about the practical use of antidepressants with so many drugs to choose from. Over the last few years, three new antidepressants have come out: vilazodone (Viibryd), vortioxetine (Trintellix), and levomilnacipran (Fetzima). My sense is that an awful lot of clinicians still haven’t changed their antidepressant choices all that much, even with these new meds out. Are we missing the boat?

Dr. Gitlin: Not necessarily. But before getting into the specifics of these meds, I think it’s fair to acknowledge that it is discouraging to clinicians—and our patients—that we still do not have an antidepressant that’s more effective than imipramine, which came out in the early to mid 1950s. SSRIs are not more effective than tricyclics; SNRIs are really not more effective than SSRIs; and the newer ones you mentioned are no more effective than the SSRIs or SNRIs. So, on one hand, I love the idea that I have options, whether it’s an antidepressant, mood stabilizer, benzo, or antipsychotic—but do I think that we have genuinely different options based on the fact that these new medicines are out? I actually don’t.

TCPR: Okay, they’re not miracle drugs, but I would like to hear your thoughts about their potential uses. Let’s start with vilazodone. Is it essentially an SSRI?

Dr. Gitlin: It has a mixture of effects. It has serotonin transporter–blocking properties like an SSRI, and it seems to affect the serotonin 1A receptor like buspirone. So your first thought might be that it would be a good medication for depression with prominent comorbid anxiety, a symptom profile for which SSRIs get chosen. Yet while it has been shown to help for comorbid anxiety and for generalized anxiety disorder when compared to placebo, we don’t have data to show it’s any better than SSRIs for these conditions. More concerning is that I’ve taken people off vilazodone because it was too stimulating, which is obviously not what you want for somebody with comorbid anxiety. In that sense it feels a bit like fluoxetine, which also leads to some people feeling wired.

TCPR: Have you found any tricks with dosing that would minimize that kind of side effect?

Dr. Gitlin: Just as with fluoxetine, you would give it in the morning and tell people to hang on, because stimulation is one of the side effects of serotonergic drugs to which people are most likely to develop a tolerance. Rates of stimulation at week 6 are always much less than week 1. In terms of dosing, I generally use the manufacturer’s recommendation: Start at 10 mg, then increase to 20 mg, and then up to 40 mg. For some, I can’t get to 40 mg because of the nausea or the stimulation, but I’ve had people respond at 20 or 30 mg.

TCPR: The vilazodone package insert says that absorption is improved if you take vilazodone with food.

Dr. Gitlin: Yes, and I tell patients that they should take it with a snack. 40 mg without food is probably the equivalent of 20 mg with food, in terms of absorption.

TCPR: What about sexual dysfunction? Does vilazodone have any advantages over SSRIs?

Dr. Gitlin: There was an early study that showed no difference in sexual side effect rating between vilazodone and placebo, but it’s hard to tell what that means unless you compare it with an active agent. The FDA won’t allow the manufacturer to say that vilazodone doesn’t cause sexual side effects, and given its serotonergic mechanism, it’s not obvious why it wouldn’t cause those side effects. Have I had people who subjectively perceive that they have fewer sexual side effects on vilazodone than a classic SSRI? Yes, but the number of patients I’ve tried on the drug is too small to draw any conclusions.

TCPR: Let’s move on to vortioxetine.

Dr. Gitlin: Like vilazodone, vortioxetine has clear SSRI-like properties: It blocks the presynaptic serotonin transporter, but unlike vilazodone, it also affects many of the serotonin subreceptors prominently. So the hip way of phrasing it is to call it a “serotonin modulator” as opposed to an SSRI. Clearly, its potency at hitting the serotonin subreceptors provides it with a rather different side effect profile.

TCPR: How so?

Dr. Gitlin: Vortioxetine doesn’t feel like an SSRI, primarily because it has more GI side effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.

TCPR: How are you dosing vortioxetine typically?

Dr. Gitlin: I start at 5 mg, I go up to 10 mg, and I see 20 mg as a full dose. But the GI side effects have precluded my ability to get to 20 mg with some regularity, so I have a number of people at 5 or 10 mg.

TCPR: What about levomilnacipran?

Dr. Gitlin: Levomilnacipran is an isomer of milnacipran, which is marketed as Savella, a drug that is FDA-indicated for fibromyalgia. However, milnacipran has close to a dozen controlled studies showing that it’s an effective antidepressant. My presumption is that the firm that makes it didn’t pursue an FDA indication because it was too close to the end of milnacipran’s patent life. So what is a pharmaceutical firm to do in a situation like that? You take a very closely related drug like the isomer l-milnacipran (levomilnacipran) and you do studies presuming that you’re going to get the same clinical efficacy, which they did, and you’re going to get a longer patent life, which they also did.

TCPR: What are your initial impressions of the drug?

Dr. Gitlin: It is an SNRI, a dual action agent, so it should be compared with our other SNRIs: venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine. It is the most noradrenergic, most norepinephrine-predominant of the four of them. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are predominantly serotonergic. Duloxetine has relatively more noradrenergic effect than venlafaxine.

TCPR: What are the implications of levomilnacipran’s noradrenergic prominence?

Dr. Gitlin: It doesn’t affect levomilnacipran’s efficacy, but rather its side effect profile. It is more constipating and causes more sweating than other SNRIs because those are noradrenergic side effects.

TCPR: Let’s shift gears a bit and talk about antipsychotics used in depression. Do you believe that there is any particular reason to choose one over another?

Dr. Gitlin: There are four antipsychotics that have FDA indication as an adjunct for major depression, including olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine in Symbyax), quetiapine, aripiprazole, and most recently brexpiprazole. They all have double-blind studies with the same design: You take people with depression, you put them on antidepressants; you take the people who didn’t respond and you randomly assign them to add in a low dose of antipsychotic versus placebo. In every study—and there are over 20 double-blind trials with more than 5,000 patients combined—it’s pretty clear that the antipsychotic augments efficacy. And when it happens, it happens relatively quickly. In most of the studies, drug placebo differences are apparent within the end of week 1, week 2 at the absolute latest. There also are a fair number of other antipsychotic agents that have shown efficacy, like risperidone, ziprasidone, cariprazine, and lurasidone, so it looks as if this is close to a class effect; second-generation antipsychotics do this in general.

TCPR: How does the efficacy of antipsychotics compare with other potential augmenters?

Dr. Gitlin: The next most studied drug is lithium, with a total of 10 placebo-controlled trials and something like 270 patients. While lithium definitely shows a significant effect over placebo, it tends to be much more popular in Europe than the U.S., where antipsychotics are more commonly used as augmentation agents.

TCPR: What has been your clinical experience with using antipsychotics for depression?

Dr. Gitlin: I have found that they really do work. I tend to choose aripiprazole over quetiapine because it causes less weight gain. I have been using lurasidone (Latuda), too, which also causes less weight gain. Lurasidone doesn’t have the FDA indication, and we don’t have the studies for adjunctive use in depression, but given how robust the literature is regarding lurasidone for bipolar depression, what are the odds it would have no efficacy as an adjunct for unipolar depression? I discuss clinical practices with my colleagues, and we’ve all tried lurasidone and have the general sense that it works as well as aripiprazole or quetiapine. So that’s prescribing logically as opposed to data-based, I confess.

TCPR: It sounds like your go-to antipsychotics for depression are aripiprazole and lurasidone. How do you tend to dose these agents?

Dr. Gitlin: In general, antipsychotics for depression can be used at a lower dose than for treating psychosis or acute mania. For aripiprazole, I prescribe 5 mg pills typically, and I tell patients to start with 2.5 mg—break the pill in half. You could also prescribe 2 mg pills and just take one of those, but it is a little more financially efficient to do it my way. I tell patients to take 2.5 mg in the morning for 3 to 4 days. If they notice an effect, they can stay on the 2.5 mg. If they notice no improvement after 3 to 4 days, I’ll have them go up to 5 mg and then sit on that for up to 2 weeks. It’s a simple dose paradigm. My adjunctive dose is 2.5 to 10 mg. If patients have not responded at 10 mg, I move on to something else.

TCPR: How long should patients stay on an antipsychotic as adjunctive therapy for depression?

Dr. Gitlin: That’s not clear. Some patients will stay on these meds for years, but others use them differently, as though they are transient mood boosters. I have a number of patients who have responded to aripiprazole but then have discontinued the medication after a week or two, and they’ve stayed well. Then six months or a year later, if they have a dip, they will do another 2- or 3-week course. Nobody has studied this effect; I don’t know how frequently it actually occurs. But I certainly have seen it with a solid handful of patients who dose themselves with short bursts of aripiprazole.

TCPR: And how do you dose lurasidone?

Dr. Gitlin: I usually start with 20 mg, which is the lowest-potency tablet it comes in. If that doesn’t work, I go to 40 mg, and if 40 mg doesn’t work, I’ll probably move on. It’s important to note that lurasidone needs to be taken with a meal to optimize its bioavailability.

TCPR: What about side effects of these medications?

Dr. Gitlin: For aripiprazole, I tell people to take it in the morning because the data are pretty clear that stimulation effects, sort of like akathisia, are more common than sedation by a ratio of more than 2 to 1. About 10% of people do get sedated, and in those cases I tell them to switch their dose to the evening. I also tell people they might get a little dizzy or nauseous. At those doses, 2.5 and 5 mg, you tend not to see any other side effects. As far as lurasidone, it can be somewhat sedating but not terribly so. You can see the same drowsiness and restlessness as with aripiprazole, but you don’t see it nearly as much; there is also some nausea. Those are the major side effects. As with aripiprazole, I tend to have patients take lurasidone in the morning.

TCPR: Is there anything else patients need to know about possible side effects?

Dr. Gitlin: There is one tricky aspect, which has to do with the tardive dyskinesia (TD) informed consent. As you know, the rate of TD with second-generation agents is a fraction of what you see with first-generation agents, but not zero. Granted, all the TD data, or almost all of it, is in schizophrenia and bipolar studies that use much higher doses. Still, if I’m giving 2 mg of aripiprazole, the rate of TD at one year is probably very small, but it’s not zero. So do you tell patients that before you start or do you wait to see if you are going to keep them on the medication for an extended time period? Because, of course, by definition TD is tardive; there is no risk in the first week or two. The analogy is with all the patients treated by both psychiatrists and primary care doctors who prescribed 25 mg of quetiapine to help them sleep. Do you need to give those patients the TD warning? How many clinicians actually provide it? The field has not developed a set of coherent guidelines in this situation.

TCPR: That’s an interesting wrinkle. We now have this group of fairly safe antipsychotics and we are prescribing them to a lot more people, so I imagine that there must be some clinicians who are using them frequently and starting to think of them not as the dangerous antipsychotic agents of yesterday, but more as antidepressants. Are you conceptualizing these agents differently now?

Dr. Gitlin: There’s no doubt that second-generation agents, or at least a number of them, have prominent efficacy in certain depressive states. But at the same time, I worry about some clinicians being too cavalier. These are still powerful D2 blockers, and I have seen people with mood disorders taking aripiprazole at a low dose who have developed TD. It happens. I think we have to treat these powerful D2 blockers with great respect. They are wonderful medicines, but they are not benign.

General PsychiatryDr. Gitlin: Not necessarily. But before getting into the specifics of these meds, I think it’s fair to acknowledge that it is discouraging to clinicians—and our patients—that we still do not have an antidepressant that’s more effective than imipramine, which came out in the early to mid 1950s. SSRIs are not more effective than tricyclics; SNRIs are really not more effective than SSRIs; and the newer ones you mentioned are no more effective than the SSRIs or SNRIs. So, on one hand, I love the idea that I have options, whether it’s an antidepressant, mood stabilizer, benzo, or antipsychotic—but do I think that we have genuinely different options based on the fact that these new medicines are out? I actually don’t.

TCPR: Okay, they’re not miracle drugs, but I would like to hear your thoughts about their potential uses. Let’s start with vilazodone. Is it essentially an SSRI?

Dr. Gitlin: It has a mixture of effects. It has serotonin transporter–blocking properties like an SSRI, and it seems to affect the serotonin 1A receptor like buspirone. So your first thought might be that it would be a good medication for depression with prominent comorbid anxiety, a symptom profile for which SSRIs get chosen. Yet while it has been shown to help for comorbid anxiety and for generalized anxiety disorder when compared to placebo, we don’t have data to show it’s any better than SSRIs for these conditions. More concerning is that I’ve taken people off vilazodone because it was too stimulating, which is obviously not what you want for somebody with comorbid anxiety. In that sense it feels a bit like fluoxetine, which also leads to some people feeling wired.

TCPR: Have you found any tricks with dosing that would minimize that kind of side effect?

Dr. Gitlin: Just as with fluoxetine, you would give it in the morning and tell people to hang on, because stimulation is one of the side effects of serotonergic drugs to which people are most likely to develop a tolerance. Rates of stimulation at week 6 are always much less than week 1. In terms of dosing, I generally use the manufacturer’s recommendation: Start at 10 mg, then increase to 20 mg, and then up to 40 mg. For some, I can’t get to 40 mg because of the nausea or the stimulation, but I’ve had people respond at 20 or 30 mg.

TCPR: The vilazodone package insert says that absorption is improved if you take vilazodone with food.

Dr. Gitlin: Yes, and I tell patients that they should take it with a snack. 40 mg without food is probably the equivalent of 20 mg with food, in terms of absorption.

TCPR: What about sexual dysfunction? Does vilazodone have any advantages over SSRIs?

Dr. Gitlin: There was an early study that showed no difference in sexual side effect rating between vilazodone and placebo, but it’s hard to tell what that means unless you compare it with an active agent. The FDA won’t allow the manufacturer to say that vilazodone doesn’t cause sexual side effects, and given its serotonergic mechanism, it’s not obvious why it wouldn’t cause those side effects. Have I had people who subjectively perceive that they have fewer sexual side effects on vilazodone than a classic SSRI? Yes, but the number of patients I’ve tried on the drug is too small to draw any conclusions.

TCPR: Let’s move on to vortioxetine.

Dr. Gitlin: Like vilazodone, vortioxetine has clear SSRI-like properties: It blocks the presynaptic serotonin transporter, but unlike vilazodone, it also affects many of the serotonin subreceptors prominently. So the hip way of phrasing it is to call it a “serotonin modulator” as opposed to an SSRI. Clearly, its potency at hitting the serotonin subreceptors provides it with a rather different side effect profile.

TCPR: How so?

Dr. Gitlin: Vortioxetine doesn’t feel like an SSRI, primarily because it has more GI side effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.

TCPR: How are you dosing vortioxetine typically?

Dr. Gitlin: I start at 5 mg, I go up to 10 mg, and I see 20 mg as a full dose. But the GI side effects have precluded my ability to get to 20 mg with some regularity, so I have a number of people at 5 or 10 mg.

TCPR: What about levomilnacipran?

Dr. Gitlin: Levomilnacipran is an isomer of milnacipran, which is marketed as Savella, a drug that is FDA-indicated for fibromyalgia. However, milnacipran has close to a dozen controlled studies showing that it’s an effective antidepressant. My presumption is that the firm that makes it didn’t pursue an FDA indication because it was too close to the end of milnacipran’s patent life. So what is a pharmaceutical firm to do in a situation like that? You take a very closely related drug like the isomer l-milnacipran (levomilnacipran) and you do studies presuming that you’re going to get the same clinical efficacy, which they did, and you’re going to get a longer patent life, which they also did.

TCPR: What are your initial impressions of the drug?

Dr. Gitlin: It is an SNRI, a dual action agent, so it should be compared with our other SNRIs: venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine. It is the most noradrenergic, most norepinephrine-predominant of the four of them. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are predominantly serotonergic. Duloxetine has relatively more noradrenergic effect than venlafaxine.

TCPR: What are the implications of levomilnacipran’s noradrenergic prominence?

Dr. Gitlin: It doesn’t affect levomilnacipran’s efficacy, but rather its side effect profile. It is more constipating and causes more sweating than other SNRIs because those are noradrenergic side effects.

TCPR: Let’s shift gears a bit and talk about antipsychotics used in depression. Do you believe that there is any particular reason to choose one over another?

Dr. Gitlin: There are four antipsychotics that have FDA indication as an adjunct for major depression, including olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine in Symbyax), quetiapine, aripiprazole, and most recently brexpiprazole. They all have double-blind studies with the same design: You take people with depression, you put them on antidepressants; you take the people who didn’t respond and you randomly assign them to add in a low dose of antipsychotic versus placebo. In every study—and there are over 20 double-blind trials with more than 5,000 patients combined—it’s pretty clear that the antipsychotic augments efficacy. And when it happens, it happens relatively quickly. In most of the studies, drug placebo differences are apparent within the end of week 1, week 2 at the absolute latest. There also are a fair number of other antipsychotic agents that have shown efficacy, like risperidone, ziprasidone, cariprazine, and lurasidone, so it looks as if this is close to a class effect; second-generation antipsychotics do this in general.

TCPR: How does the efficacy of antipsychotics compare with other potential augmenters?

Dr. Gitlin: The next most studied drug is lithium, with a total of 10 placebo-controlled trials and something like 270 patients. While lithium definitely shows a significant effect over placebo, it tends to be much more popular in Europe than the U.S., where antipsychotics are more commonly used as augmentation agents.

TCPR: What has been your clinical experience with using antipsychotics for depression?

Dr. Gitlin: I have found that they really do work. I tend to choose aripiprazole over quetiapine because it causes less weight gain. I have been using lurasidone (Latuda), too, which also causes less weight gain. Lurasidone doesn’t have the FDA indication, and we don’t have the studies for adjunctive use in depression, but given how robust the literature is regarding lurasidone for bipolar depression, what are the odds it would have no efficacy as an adjunct for unipolar depression? I discuss clinical practices with my colleagues, and we’ve all tried lurasidone and have the general sense that it works as well as aripiprazole or quetiapine. So that’s prescribing logically as opposed to data-based, I confess.

TCPR: It sounds like your go-to antipsychotics for depression are aripiprazole and lurasidone. How do you tend to dose these agents?

Dr. Gitlin: In general, antipsychotics for depression can be used at a lower dose than for treating psychosis or acute mania. For aripiprazole, I prescribe 5 mg pills typically, and I tell patients to start with 2.5 mg—break the pill in half. You could also prescribe 2 mg pills and just take one of those, but it is a little more financially efficient to do it my way. I tell patients to take 2.5 mg in the morning for 3 to 4 days. If they notice an effect, they can stay on the 2.5 mg. If they notice no improvement after 3 to 4 days, I’ll have them go up to 5 mg and then sit on that for up to 2 weeks. It’s a simple dose paradigm. My adjunctive dose is 2.5 to 10 mg. If patients have not responded at 10 mg, I move on to something else.

TCPR: How long should patients stay on an antipsychotic as adjunctive therapy for depression?

Dr. Gitlin: That’s not clear. Some patients will stay on these meds for years, but others use them differently, as though they are transient mood boosters. I have a number of patients who have responded to aripiprazole but then have discontinued the medication after a week or two, and they’ve stayed well. Then six months or a year later, if they have a dip, they will do another 2- or 3-week course. Nobody has studied this effect; I don’t know how frequently it actually occurs. But I certainly have seen it with a solid handful of patients who dose themselves with short bursts of aripiprazole.

TCPR: And how do you dose lurasidone?

Dr. Gitlin: I usually start with 20 mg, which is the lowest-potency tablet it comes in. If that doesn’t work, I go to 40 mg, and if 40 mg doesn’t work, I’ll probably move on. It’s important to note that lurasidone needs to be taken with a meal to optimize its bioavailability.

TCPR: What about side effects of these medications?

Dr. Gitlin: For aripiprazole, I tell people to take it in the morning because the data are pretty clear that stimulation effects, sort of like akathisia, are more common than sedation by a ratio of more than 2 to 1. About 10% of people do get sedated, and in those cases I tell them to switch their dose to the evening. I also tell people they might get a little dizzy or nauseous. At those doses, 2.5 and 5 mg, you tend not to see any other side effects. As far as lurasidone, it can be somewhat sedating but not terribly so. You can see the same drowsiness and restlessness as with aripiprazole, but you don’t see it nearly as much; there is also some nausea. Those are the major side effects. As with aripiprazole, I tend to have patients take lurasidone in the morning.

TCPR: Is there anything else patients need to know about possible side effects?

Dr. Gitlin: There is one tricky aspect, which has to do with the tardive dyskinesia (TD) informed consent. As you know, the rate of TD with second-generation agents is a fraction of what you see with first-generation agents, but not zero. Granted, all the TD data, or almost all of it, is in schizophrenia and bipolar studies that use much higher doses. Still, if I’m giving 2 mg of aripiprazole, the rate of TD at one year is probably very small, but it’s not zero. So do you tell patients that before you start or do you wait to see if you are going to keep them on the medication for an extended time period? Because, of course, by definition TD is tardive; there is no risk in the first week or two. The analogy is with all the patients treated by both psychiatrists and primary care doctors who prescribed 25 mg of quetiapine to help them sleep. Do you need to give those patients the TD warning? How many clinicians actually provide it? The field has not developed a set of coherent guidelines in this situation.

TCPR: That’s an interesting wrinkle. We now have this group of fairly safe antipsychotics and we are prescribing them to a lot more people, so I imagine that there must be some clinicians who are using them frequently and starting to think of them not as the dangerous antipsychotic agents of yesterday, but more as antidepressants. Are you conceptualizing these agents differently now?

Dr. Gitlin: There’s no doubt that second-generation agents, or at least a number of them, have prominent efficacy in certain depressive states. But at the same time, I worry about some clinicians being too cavalier. These are still powerful D2 blockers, and I have seen people with mood disorders taking aripiprazole at a low dose who have developed TD. It happens. I think we have to treat these powerful D2 blockers with great respect. They are wonderful medicines, but they are not benign.

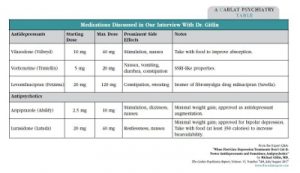

Medications Discussed in Our Interview with Dr. Gitlin

(Click here to view as a full-size PDF.)

Issue Date: July 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)