How to Diagnose Bipolar Disorder

Gordon Parker, MD, PhD, DSc.

Scientia Professor of psychiatry at the University of New South Wales. In 2002 he founded the Black Dog Institute, a clinical research center for mood disorders. Dr. Parker’s research has focused on the phenomenology and diagnosis of depression and bipolar disorder.

Dr. Parker has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Gordon Parker, MD, PhD, DSc.

Scientia Professor of psychiatry at the University of New South Wales. In 2002 he founded the Black Dog Institute, a clinical research center for mood disorders. Dr. Parker’s research has focused on the phenomenology and diagnosis of depression and bipolar disorder.

Dr. Parker has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: When I ask a depressed patient if they’ve ever had manic symptoms, I often run into a problem. They say, “Of course I feel more confident, energetic, and happy ... when I’m not depressed.”

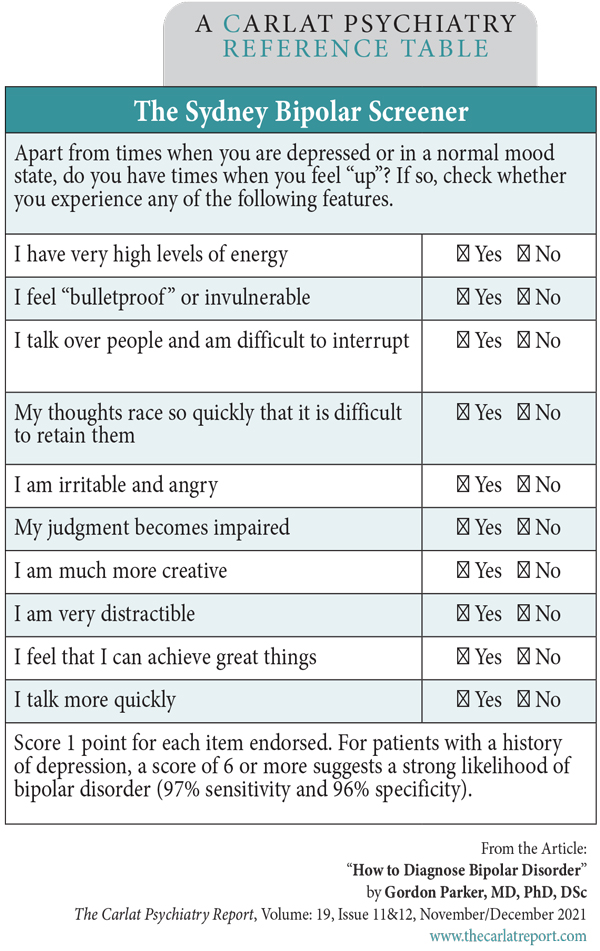

Dr. Parker: As it can be hard to tease apart true hypomania from normal happiness, we’ve developed a rating scale to assist, the Sydney Bipolar Screener. We evaluated 94 symptoms of mania and hypomania in patients who were already diagnosed with bipolar or unipolar disorder. We asked the patients with bipolar disorder to check the items that reflected their “highs,” and the unipolar patients to check the items that described times when they were “happy.” We used a machine learning strategy to filter out the items that overlapped with normal happiness. In the end, that whittled the set down to 10 symptoms that separated bipolar from unipolar with a high predictive accuracy—over 90% (Parker G et al, J Affect Disord 2021;281:505–509). (Editor’s note: See The Sydney Bipolar Screener table below.)

TCPR: What is the main thing that separates out the bipolars?

Dr. Parker: Energy. The most distinguishing item was “I have very high levels of energy.” Items related to euphoria and heightened emotions didn’t make the cut. One item that didn’t make the top 10 but that we do see a lot in mania and hypomania is decreased need for sleep. I think the key issue is not just asking “Do you need less sleep?” but extending the question by saying “Do you sleep less and find that you’re not tired the next day?”

TCPR: What’s your top screening question for bipolar disorder?

Dr. Parker: The first screening question I use in my clinical assessment is, “Apart from the times when you’re depressed and when your mood is normal, do you have periods when you’re energized and wired?” This puts energy front and center. Energy was not part of the core “Criterion A” definition of mania in DSM-IV, but they brought it in for DSM-5, which I think was wise.

TCPR: You’re leading a task force that is proposing changes to DSM criteria for mania and hypomania. How would you change the core definition: “A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood and abnormally and persistently goal-directed behavior or energy”?

Dr. Parker: We have a minor tweak for that one. We’d emphasize that the elevated mood is not just happiness but is an “overshoot.” Thus: “A distinct period of abnormal and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, with the individual feeling energized and ‘wired,’ and which is perceived as an ‘overshoot’ and not simply a state of happiness, and generally oscillating with periods of depression.”

TCPR: You also added a part about cycling with depression.

Dr. Parker: That can help reduce false positives. I think it’s very rare for people to only have hypomanic or manic episodes without depressions. In my experience, I’ve seen maybe three or four people like that over my lifetime.

TCPR: Are bipolar depressions different from unipolar depressions?

Dr. Parker: Bipolar depression is more likely to be melancholic, and possibly psychotic. When I say “melancholic,” I’m not referring to the DSM criteria for melancholic features. I’m speaking more generally of a severe depressed state where their mood is nonreactive, they have anhedonia, a distinct lack of energy, foggy concentration, and maybe other psychomotor changes. So when I want to establish a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, I look for manic features but I also check out the nature of their depressions.

TCPR: What else would you change in the DSM criteria for bipolar?

Dr. Parker: Another problem is how the DSM separates mania from hypomania. First, the use of the same list of symptoms for both states is problematic. To separate them, the DSM uses severity (mania causes significant impairment), duration (hypomania is at least four days while mania is at least seven days), and hospitalization and psychotic features (these last two automatically shift the diagnosis to mania). I don’t know of any other medical condition where hospitalization is a criterion. It depends too much on external variables like social supports and the health care system.

TCPR: What about duration?

Dr. Parker: The problem there is that the four- and seven-day cutoffs the DSM uses for hypomania and mania have never been empirically validated. Patients who meet the full duration criterion have the same clinical features as those whose elevated moods are classic and recurrent, but shorter in duration (Parker G and Fletcher K, J Affect Disord 2014;152–154:57–64). Even when patients meet the full duration criterion, their typical episodes tend to be shorter. For 60% of patients with bipolar II, the average episode of hypomania lasts fewer than four days, and for 40% of patients with bipolar I, the average mania lasts fewer than seven days. In practice, when you ask a patient how long their episodes last, their answer is likely to reflect their typical episode, which means you’ll miss a lot of people with true bipolar disorder by applying the DSM-5 duration criterion.

TCPR: A lot of papers have argued for reducing the duration, particularly with hypomania. Why has DSM stuck with it?

Dr. Parker: I think they’re being conservative and trying to respect concerns about overdiagnosis, but I think those concerns can be addressed by more precise definitional criteria rather than by a “safety” duration period. Technically DSM-5 does recognize the short-duration cases with “depressive episodes with short-duration hypomania,” but that’s in the back of the book as a “condition for further study.”

TCPR: What separates mania from hypomania in your view?

Dr. Parker: For me, it is the presence of psychotic features. If you have psychosis during an elevated state, it’s bipolar I. If you don’t, then it’s bipolar II.

TCPR: Do you mean delusions and hallucinations, or do you take a broader view of psychosis, including distorted thinking and thought-blocking?

Dr. Parker: I’m speaking just of delusions and hallucinations. These aren’t always easy to diagnose, as there is a fine line between a delusion and an overvalued idea. For example, the average patient becomes grandiose during a high. They think they’re going to be the boss of the company or write the great Australian novel. To diagnose psychosis, I look for pretty black-and-white features such as, “When I’m high, I have a voice in my head telling me I am God.” I’m looking for distinctive and clear-cut psychotic delusions or hallucinations.

TCPR: There is also a fine line between heightened sensations and hallucinations.

Dr. Parker: Yes, and that’s important to recognize because patients with both bipolar I and bipolar II tend to have highly sensitive perceptions, but I would not classify those as hallucinations (Parker G et al, Australas Psychiatry 2018;26(4):384–387). I have patients that will say, “I can hear a car in the street three blocks away” and I can’t hear anything. Smells are more powerful. One patient stepped on some dog poo while in an elevated mood—they wiped it off, but they could smell it for the whole day. Sometimes these sensations are a source of creativity. One patient told me when she’s listening to an orchestra, she has the capacity to bring out and separate every instrument and then rejoin them together.

TCPR: Does a patient’s judgment tell you about possible delusional thinking? For example, suppose a patient with bipolar disorder tells you they’ve taken out all their retirement savings to start a chain of ice cream stores. They teach elementary school and have no business experience. That’s out of touch with reality, but is it delusional?

Dr. Parker: I would strongly consider psychosis in that case because it suggests delusional confidence. On the other hand, if a multimillionaire took out $200,000 to start a new business, I’d be less inclined to think it was delusional. Mania and hypomania also tend to differ in how the patient recalls the episode. After the episode, the hypomanic patient is likely to feel great shame about what they did while the manic patient may not remember it or be inclined to deny it.

TCPR: One way the DSM separates mania from hypomania is by the level of impairment. What’s wrong with that definition?

Dr. Parker: The DSM wording is imprecise: “marked impairment” for mania and “not severe enough to cause marked impairment” in hypomania. How are clinicians meant to judge the difference? Further, it puts the weight on impairment, when in reality there’s a significant percentage of patients with mania and hypomania who say their functioning is distinctly improved, and they may well be right if creativity or productivity is the benchmark for functioning.

TCPR: Getting back to hypomania vs normal happiness, is there a clear, categorical line between them, or are they on a continuum?

Dr. Parker: Our studies support a categorical view. When we plot the answers to a bipolar screening measure, we observe a bimodal distribution, so there is a clear separation between normal elevated mood and the hypomania of bipolar disorder. And when we throw in bipolar I patients we get a trimodal distribution, so there is a categorical separation between hypomania and mania as well (Parker G et al, Psychiatry Res 2021;297:113719).

TCPR: Sometimes it doesn’t seem so clear cut in practice.

Dr. Parker: In clinical practice, about 2% or 3% of patients who present for evaluation of bipolar have hypomanias that are so mild that I’m not entirely sure that they’ve truly got bipolar disorder, but it’s a very, very small minority. If you go through the diagnostic steps, you can usually identify the patients with true bipolar disorder.

TCPR: What are those steps?

Dr. Parker: Start with a screening question, like the one I suggested about energy. If they say “no” or are unsure, double-check by asking, “You don’t have times when you are more energized, elated, and overconfident, in a way that is distinct from your normal self?” If one of those tries is a “yes,” move forward and check for the rest of the DSM symptoms of hypomania/mania. Ideally, you want to identify clear and unequivocal episodes of hypomania or mania. Then ask about the depressive phases. Are the depressions recurrent and cyclical? Do at least some of them have melancholic features in the way I described? Next, I would look for a family history. Patients with true bipolar disorder will almost invariably report a family history of either depression or bipolar in their first- or second-degree relatives. About half will report bipolar in their family, but the other half will usually report depression (Suppes T et al, J Affect Disord 2001;67(1–3):45–59).

TCPR: Anything else?

Dr. Parker: Finally, age of onset can also be helpful, as most bipolar disorder starts in adolescence, particularly between ages 15 and 20. Age of onset is a strong indicator, and it can help to differentiate bipolar disorder from other conditions that share some symptomatic overlap with hypomania, like ADHD and borderline personality disorder. Those two disorders tend to start much earlier. (Editor’s note: Borderline personality disorder cannot be diagnosed until age 18, but adults with this disorder can usually trace some of their symptoms back to early childhood.)

TCPR: If the patient checks all those boxes, are you pretty sure they have bipolar disorder?

Dr. Parker: Yes, and I’ll tell them that. I always apologize first and say, “This is going to sound a bit arrogant, but I believe with a 100% level of confidence that you’ve got (say) bipolar II.” Or if I’m not 100% confident, I’ll say so and explain why. It may be that they don’t check all the boxes, or there are other things going on like substance use that might explain the symptoms. And then I’ll detail what needs to be done to obtain a firmer diagnosis.

TCPR: You’re very direct about it. How do patients respond?

Dr. Parker: They seem to appreciate a firm diagnosis as it allows them to get on with their lives. They now know what they’ve got and they can go on Google and read about it. And, of course, you hope to find the right medication and they’ll have it all come under control. I believe that most people with a bipolar condition do well when we find right medication.

TCPR: The right medication may be different for everyone, but what are the go-to meds that you often start with?

Dr. Parker: My preferred drugs are lithium for bipolar I and lamotrigine for bipolar II.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Parker.

Table: The Sydney Bipolar Screener

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

![]() Stay tuned for our podcast, “A New Way to Diagnose Bipolar: An Interview With Gordon Parker.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

Stay tuned for our podcast, “A New Way to Diagnose Bipolar: An Interview With Gordon Parker.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)