Home » Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder: An Overview

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder: An Overview

March 1, 2022

From The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report

Mikveh Warshaw, NP.

Psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner, Community Health Center Inc. and faculty member of Center for Key Populations (CKP) Program, Middletown, CT.

Ms. Warshaw has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is the most common substance use disorder by far, with a lifetime prevalence of nearly 30%. It is also vastly undertreated; less than 20% of people with AUD ever receive treatment (Grant BF et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(8):757–766). To make matters worse, there are only three FDA-approved medications for AUD: disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone. However, there are quite a few other medications being used off label to treat AUD. We’ll walk you through the options, the current evidence, and some ways of choosing between the available medications.

FDA-approved meds

Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol)

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that decreases alcohol cravings by blunting the reinforcing pleasure induced by a drink. Many patients find naltrexone to be particularly user-friendly because it is usually well tolerated, can be taken as a single daily pill, and can be started while actively drinking. It is generally taken as a daily 50 mg dose, though 25–100 mg doses are also possible. While alternate dosing strategies exist, a single daily dose seems to be as effective as any other strategy and is certainly the simplest option (Jonas DE et al, JAMA 2014:311(18):1889–1900).

Naltrexone is also available as a 380 mg monthly injectable (Vivitrol), which is a great option when adherence is a concern, though it is important to note that we lack quality head-to-head trials to determine the comparative efficacy of oral versus injectable naltrexone. Pain at the injection site can be problematic, and at least anecdotally, the naltrexone injection is more uncomfortable than other depot medications for some patients. High cost and special storage requirements (ie, refrigeration) can be additional barriers.

Except in special circumstances, naltrexone can’t be administered alongside opioids, as it can precipitate immediate withdrawal. On the other hand, the naltrexone injection is approved for treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD), so it can be utilized for patients with comorbid AUD and OUD as long as they don’t have any opioids in their system at the time of administration. Naltrexone can be rough on the liver, so it is not recommended for patients with acute hepatitis or transaminases that are five times the upper limit of normal or above.

Disulfiram (Antabuse)

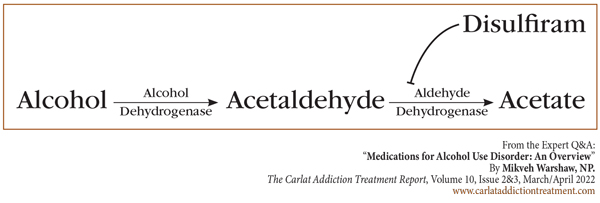

Disulfiram was approved by the FDA back in 1951 as an aversive therapy for AUD. It creates a buildup of acetaldehyde by inhibiting aldehyde dehydrogenase (refer to diagram below), causing very uncomfortable flushing, headache, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting. Many patients experiencing a disulfiram reaction will present to the hospital, and mixing large amounts of alcohol with disulfiram can cause myocardial infarction and respiratory depression.

Disulfiram can be started as soon as 12 hours after the last drink with a single dose of 250–500 mg daily. After the first two weeks, doses are typically kept to a single 250 mg daily dose to minimize hepatotoxicity. Patients should abstain from alcohol for 14 days after taking disulfiram, though in reality many can drink after seven days. Disulfiram is generally well tolerated, though it can cause an odd metallic taste. Rare but serious side effects include psychosis and severe hepatotoxicity, so liver function tests (LFTs) should be monitored. Finally, some patients are very sensitive and may react to alcohol-based hand sanitizers, mouthwash, or foods cooked with alcohol. For these patients, consider lowering the dose to 125 mg daily.

Because disulfiram is purely an aversive treatment and does not decrease alcohol cravings, it can be a bit of a double-edged sword. Patients with poor impulse control may drink alcohol with disulfiram in their system and get sick enough to require hospitalization. Other patients may stop taking the medication altogether and resume drinking. In fact, disulfiram has been shown to work only for patients who have caretakers (loved ones or a visiting nurse) directly observing adherence (Jonas et al, 2014).

Acamprosate (Campral)

Acamprosate is a viable option, especially for patients who have already achieved abstinence. Its effect size is moderate, with some studies finding that it is not quite as good as naltrexone (Anton RF et al, JAMA 2006;295(17):2003–2017); however, it is not hepatically metabolized, making it a good choice for those with liver disease. Acamprosate’s molecular structure resembles GABA, and it is thought to enhance activity of GABA-ergic systems while also blocking glutamate receptors. How this translates to decreased alcohol use is not entirely clear.

Acamprosate is dosed TID, which is a challenge for many patients. It can be started at BID dosing, but the goal is 666 mg TID since BID dosing did not achieve statistical significance over placebo in the original clinical trial. It also requires renal adjustments: Give 50% of the dose in patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) between 30 and 50 mL/min, and avoid it altogether in patients with CrCl less than 30 mL/min.

Non-FDA-approved medications

Gabapentin (Neurontin)

Gabapentin was found to be efficacious for AUD in two clinical trials (Mason BJ et al, JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(1):70–77; Furieri FA et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(11):1691–1700). The theory is that by boosting central GABA, gabapentin blunts neuronal hyperexcitability that comes from chronic drinking. It is safe for patients with liver disease but, like acamprosate, needs renal dose adjustments. Side effects include somnolence, headache, dizziness, ataxia, and peripheral edema.

Evidence shows that higher doses of gabapentin are more effective than lower doses, with one of the major gabapentin trials demonstrating clear benefit in 1800 mg versus 900 mg daily (Mason et al, 2014). Gabapentin absorption goes down as the dose goes up, known as zero-order kinetics, so the recommended target dose is 600 mg TID as opposed to the more user-friendly BID dosing. A slow titration can minimize sedation in the beginning of treatment.

Finally, be cautious in patients with comorbid OUD; gabapentin has been associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose death (Gomes T et al, PLoS Med 2017;14(10):e1002396). One trial showed that adding gabapentin to oral naltrexone improved drinking outcomes, at least over the six weeks of the trial (Anton RF et al, Am J Psych 2011;168(7):709–717).

Topiramate (Topamax)

Topiramate has been shown to reduce the number of heavy drinking days among patients still using alcohol (Johnson BA et al, JAMA 2007;298(14):1641–1651). Its mechanism of action is thought to hinge on its ability to block glutamate, which in turn reduces dopamine and dampens alcohol’s reinforcing effects.

Topiramate’s most notorious side effect is confusion, earning it the famous nickname “Dopamax.” Other common side effects include paresthesia, loss of appetite, and itching. Rare but serious side effects include metabolic acidosis and acute closed-angle glaucoma, which can manifest early as changes in color vision. In order to mitigate side effects, titrate slowly up to 100–150 mg BID over six to eight weeks, which is the dosage that confers the greatest benefit.

Other off-label options

Varenicline (Chantix)

Varenicline is well tolerated by most patients and has demonstrated potential in AUD, especially in patients who smoke, though the data are mixed. A recent meta-analysis found that varenicline decreased cravings but not actual drinking (Gandhi KD et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(2):19r12924). Interestingly, it seems that varenicline might be effective for men but not women (O’Malley SS et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75(2):129–138). At the end of the day, the evidence to recommend varenicline is not very strong, and it should be considered only after the failure of other medications with better evidence. Varenicline might have an edge over some of the other second-line medications if your patient smokes. Finally, previous concerns about adverse neuropsychiatric events were likely overblown—recent trials have reassured us that varenicline is safe to prescribe in patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders (Anthenelli RM et al, Lancet 2016;387(10037):2507–2520).

Baclofen (Lioresal)

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist thought to reduce alcohol cravings and, in turn, lead to abstinence through its GABA-ergic actions. Despite some promising early reports, further studies have revealed heterogeneous results, with baclofen performing no better than placebo on most drinking outcomes in a large meta-analysis (Rose AK and Jones A, Addiction 2018;113(8):1396–1406). Given the relatively weak evidence, we recommend trying baclofen only after other medications have failed. Keep in mind that baclofen is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant associated with toxicity and misuse, so be especially cautious if the patient is heavily drinking or taking other sedating medications (Reynolds K et al, Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020;58(7):763–772).

Ondansetron (Zofran)

Ondansetron, which you probably know as an antiemetic, has been shown to decrease drinking in several older trials (Sellers EM et al, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1994;18(4):879–885). Its anti-drinking properties are thought to come from serotonin 5-HT3 antagonism. Interestingly, researchers have thought that people who develop AUD at a young age are more likely to have disruptions in serotonin signaling, and sure enough, ondansetron does seem to be more effective for these patients (Johnson BA et al, JAMA 2000;284(8):963–971). It also seems to work better for patients who do not drink very heavily—less than 10 drinks daily. Ondansetron’s distinguishing side effect is QTc prolongation, so avoid it in patients who have cardiac disease or are taking other QTc-prolonging medications. Other side effects include increased LFTs, constipation, diarrhea, and headache. Though not entirely contraindicated, we would not recommend the use of ondansetron for patients on serotonergic medications since there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome.

SSRIs

SSRIs have been examined for their efficacy in AUD. Whether they might decrease drinking by centrally modulating serotonin, or simply by treating underlying depression and anxiety, is unclear. Either way, the data are mixed. Among the SSRIs, sertraline has some of the best evidence, particularly for patients without a family history of AUD or who developed AUD later in life (Pettinati HM et al, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24(7):1041–1049), although fluoxetine showed efficacy in early trials and citalopram has some promising preclinical data. Nothing in this class is particularly convincing. Consider SSRIs for patients who have failed other more established treatments, especially if they have comorbid depression or anxiety.

Our decision tree

With all the medication options out there, how do you choose among them for your patients? Here’s our quick decision tree:

First line

Naltrexone

Acamprosate

Second line

Gabapentin

Topiramate

Third line

Baclofen

Disulfiram

Ondansetron

SSRIs

Varenicline

CATR Verdict: We recommend naltrexone and acamprosate as first-line treatments, gabapentin and topiramate as second line, and all the rest as third line. Choose meds based on patient characteristics and side effect profile. For example, favor acamprosate and gabapentin for patients with liver disease, favor injectable naltrexone for those with adherence issues or comorbid OUD, and avoid disulfiram for patients with poor impulse control.

Addiction TreatmentFDA-approved meds

Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol)

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that decreases alcohol cravings by blunting the reinforcing pleasure induced by a drink. Many patients find naltrexone to be particularly user-friendly because it is usually well tolerated, can be taken as a single daily pill, and can be started while actively drinking. It is generally taken as a daily 50 mg dose, though 25–100 mg doses are also possible. While alternate dosing strategies exist, a single daily dose seems to be as effective as any other strategy and is certainly the simplest option (Jonas DE et al, JAMA 2014:311(18):1889–1900).

Naltrexone is also available as a 380 mg monthly injectable (Vivitrol), which is a great option when adherence is a concern, though it is important to note that we lack quality head-to-head trials to determine the comparative efficacy of oral versus injectable naltrexone. Pain at the injection site can be problematic, and at least anecdotally, the naltrexone injection is more uncomfortable than other depot medications for some patients. High cost and special storage requirements (ie, refrigeration) can be additional barriers.

Except in special circumstances, naltrexone can’t be administered alongside opioids, as it can precipitate immediate withdrawal. On the other hand, the naltrexone injection is approved for treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD), so it can be utilized for patients with comorbid AUD and OUD as long as they don’t have any opioids in their system at the time of administration. Naltrexone can be rough on the liver, so it is not recommended for patients with acute hepatitis or transaminases that are five times the upper limit of normal or above.

Disulfiram (Antabuse)

Disulfiram was approved by the FDA back in 1951 as an aversive therapy for AUD. It creates a buildup of acetaldehyde by inhibiting aldehyde dehydrogenase (refer to diagram below), causing very uncomfortable flushing, headache, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting. Many patients experiencing a disulfiram reaction will present to the hospital, and mixing large amounts of alcohol with disulfiram can cause myocardial infarction and respiratory depression.

Disulfiram can be started as soon as 12 hours after the last drink with a single dose of 250–500 mg daily. After the first two weeks, doses are typically kept to a single 250 mg daily dose to minimize hepatotoxicity. Patients should abstain from alcohol for 14 days after taking disulfiram, though in reality many can drink after seven days. Disulfiram is generally well tolerated, though it can cause an odd metallic taste. Rare but serious side effects include psychosis and severe hepatotoxicity, so liver function tests (LFTs) should be monitored. Finally, some patients are very sensitive and may react to alcohol-based hand sanitizers, mouthwash, or foods cooked with alcohol. For these patients, consider lowering the dose to 125 mg daily.

Because disulfiram is purely an aversive treatment and does not decrease alcohol cravings, it can be a bit of a double-edged sword. Patients with poor impulse control may drink alcohol with disulfiram in their system and get sick enough to require hospitalization. Other patients may stop taking the medication altogether and resume drinking. In fact, disulfiram has been shown to work only for patients who have caretakers (loved ones or a visiting nurse) directly observing adherence (Jonas et al, 2014).

Image: Disulfiram Reaction Pathway

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Acamprosate (Campral)

Acamprosate is a viable option, especially for patients who have already achieved abstinence. Its effect size is moderate, with some studies finding that it is not quite as good as naltrexone (Anton RF et al, JAMA 2006;295(17):2003–2017); however, it is not hepatically metabolized, making it a good choice for those with liver disease. Acamprosate’s molecular structure resembles GABA, and it is thought to enhance activity of GABA-ergic systems while also blocking glutamate receptors. How this translates to decreased alcohol use is not entirely clear.

Acamprosate is dosed TID, which is a challenge for many patients. It can be started at BID dosing, but the goal is 666 mg TID since BID dosing did not achieve statistical significance over placebo in the original clinical trial. It also requires renal adjustments: Give 50% of the dose in patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) between 30 and 50 mL/min, and avoid it altogether in patients with CrCl less than 30 mL/min.

Non-FDA-approved medications

Gabapentin (Neurontin)

Gabapentin was found to be efficacious for AUD in two clinical trials (Mason BJ et al, JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(1):70–77; Furieri FA et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(11):1691–1700). The theory is that by boosting central GABA, gabapentin blunts neuronal hyperexcitability that comes from chronic drinking. It is safe for patients with liver disease but, like acamprosate, needs renal dose adjustments. Side effects include somnolence, headache, dizziness, ataxia, and peripheral edema.

Evidence shows that higher doses of gabapentin are more effective than lower doses, with one of the major gabapentin trials demonstrating clear benefit in 1800 mg versus 900 mg daily (Mason et al, 2014). Gabapentin absorption goes down as the dose goes up, known as zero-order kinetics, so the recommended target dose is 600 mg TID as opposed to the more user-friendly BID dosing. A slow titration can minimize sedation in the beginning of treatment.

Finally, be cautious in patients with comorbid OUD; gabapentin has been associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose death (Gomes T et al, PLoS Med 2017;14(10):e1002396). One trial showed that adding gabapentin to oral naltrexone improved drinking outcomes, at least over the six weeks of the trial (Anton RF et al, Am J Psych 2011;168(7):709–717).

Topiramate (Topamax)

Topiramate has been shown to reduce the number of heavy drinking days among patients still using alcohol (Johnson BA et al, JAMA 2007;298(14):1641–1651). Its mechanism of action is thought to hinge on its ability to block glutamate, which in turn reduces dopamine and dampens alcohol’s reinforcing effects.

Topiramate’s most notorious side effect is confusion, earning it the famous nickname “Dopamax.” Other common side effects include paresthesia, loss of appetite, and itching. Rare but serious side effects include metabolic acidosis and acute closed-angle glaucoma, which can manifest early as changes in color vision. In order to mitigate side effects, titrate slowly up to 100–150 mg BID over six to eight weeks, which is the dosage that confers the greatest benefit.

Other off-label options

Varenicline (Chantix)

Varenicline is well tolerated by most patients and has demonstrated potential in AUD, especially in patients who smoke, though the data are mixed. A recent meta-analysis found that varenicline decreased cravings but not actual drinking (Gandhi KD et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(2):19r12924). Interestingly, it seems that varenicline might be effective for men but not women (O’Malley SS et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75(2):129–138). At the end of the day, the evidence to recommend varenicline is not very strong, and it should be considered only after the failure of other medications with better evidence. Varenicline might have an edge over some of the other second-line medications if your patient smokes. Finally, previous concerns about adverse neuropsychiatric events were likely overblown—recent trials have reassured us that varenicline is safe to prescribe in patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders (Anthenelli RM et al, Lancet 2016;387(10037):2507–2520).

Baclofen (Lioresal)

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist thought to reduce alcohol cravings and, in turn, lead to abstinence through its GABA-ergic actions. Despite some promising early reports, further studies have revealed heterogeneous results, with baclofen performing no better than placebo on most drinking outcomes in a large meta-analysis (Rose AK and Jones A, Addiction 2018;113(8):1396–1406). Given the relatively weak evidence, we recommend trying baclofen only after other medications have failed. Keep in mind that baclofen is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant associated with toxicity and misuse, so be especially cautious if the patient is heavily drinking or taking other sedating medications (Reynolds K et al, Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020;58(7):763–772).

Ondansetron (Zofran)

Ondansetron, which you probably know as an antiemetic, has been shown to decrease drinking in several older trials (Sellers EM et al, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1994;18(4):879–885). Its anti-drinking properties are thought to come from serotonin 5-HT3 antagonism. Interestingly, researchers have thought that people who develop AUD at a young age are more likely to have disruptions in serotonin signaling, and sure enough, ondansetron does seem to be more effective for these patients (Johnson BA et al, JAMA 2000;284(8):963–971). It also seems to work better for patients who do not drink very heavily—less than 10 drinks daily. Ondansetron’s distinguishing side effect is QTc prolongation, so avoid it in patients who have cardiac disease or are taking other QTc-prolonging medications. Other side effects include increased LFTs, constipation, diarrhea, and headache. Though not entirely contraindicated, we would not recommend the use of ondansetron for patients on serotonergic medications since there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome.

SSRIs

SSRIs have been examined for their efficacy in AUD. Whether they might decrease drinking by centrally modulating serotonin, or simply by treating underlying depression and anxiety, is unclear. Either way, the data are mixed. Among the SSRIs, sertraline has some of the best evidence, particularly for patients without a family history of AUD or who developed AUD later in life (Pettinati HM et al, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24(7):1041–1049), although fluoxetine showed efficacy in early trials and citalopram has some promising preclinical data. Nothing in this class is particularly convincing. Consider SSRIs for patients who have failed other more established treatments, especially if they have comorbid depression or anxiety.

Our decision tree

With all the medication options out there, how do you choose among them for your patients? Here’s our quick decision tree:

First line

Naltrexone

- Our first choice for most patients

- Effective whether patients are drinking or not

- Can be given orally or as a long-acting injectable

- Cannot combine with opioids, but a good option for patients with comorbid OUD

Acamprosate

- Second choice after naltrexone

- Mainly indicated for patients who are already abstinent

- Good for patients with liver disease; renal dosing necessary

Second line

Gabapentin

- Effective but can be misused

- Associated with increased risk of opioid overdose

Topiramate

- Effective whether patients are drinking or not

- Cognitive and other side effects problematic

Third line

Baclofen

- Caution in patients using other CNS depressants

- Like gabapentin, probably effective but can be misused

Disulfiram

- Only for patients who are abstinent and highly motivated

- Observed administration is helpful—in fact, it might be necessary

- Monitor LFTs periodically

Ondansetron

- Most evidence in early-onset AUD

- Can prolong QTc, so avoid in cardiac disease

SSRIs

- Low efficacy as a monotherapy

- Especially useful for patients with comorbid depression or anxiety

Varenicline

- Especially useful for patients who smoke

CATR Verdict: We recommend naltrexone and acamprosate as first-line treatments, gabapentin and topiramate as second line, and all the rest as third line. Choose meds based on patient characteristics and side effect profile. For example, favor acamprosate and gabapentin for patients with liver disease, favor injectable naltrexone for those with adherence issues or comorbid OUD, and avoid disulfiram for patients with poor impulse control.

Issue Date: March 1, 2022

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)