Three Buprenorphine Dosing Strategies When Transitioning From Other Opioids

Buprenorphine is a first-line treatment for opioid use disorder. However, as a high-affinity mu-opioid partial agonist, providers must time its initial administration correctly. If given too early, while other opioids are still in the system, it can precipitate withdrawal symptoms (see CATR Nov/Dec 2021).

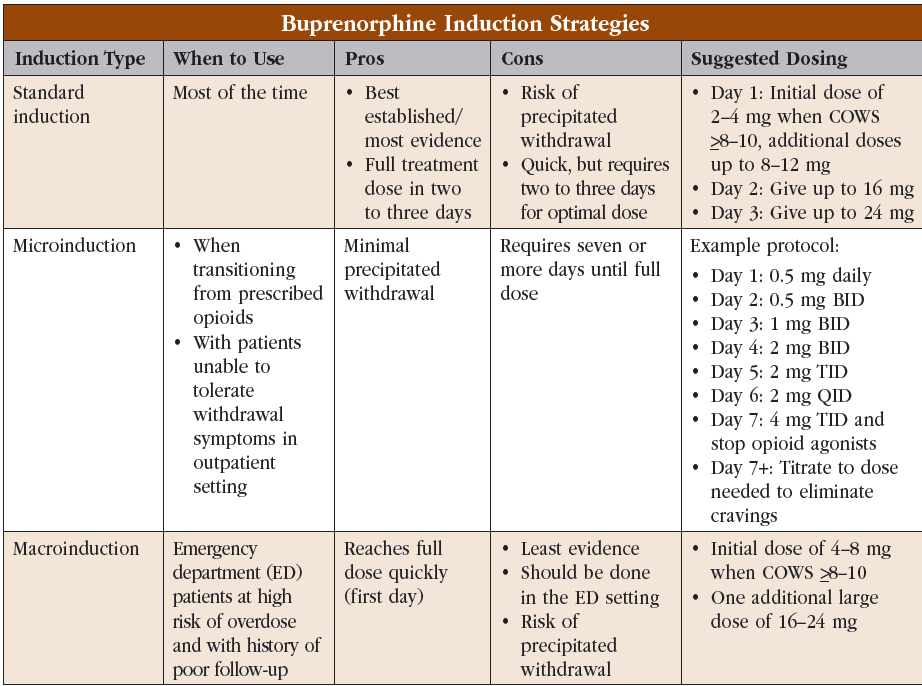

The standard method of buprenorphine induction involves having patients abstain from opioids and start buprenorphine once they are in mild to moderate withdrawal. Though this method is still the gold standard, the timing can be unpredictable given the possible involvement of fentanyl, fentanyl derivates, and other high-potency opioids. To address this, researchers and clinics have developed two new strategies, microinduction and macroinduction. Below, we will explain the basics of the three methods, detail their advantages and disadvantages, and suggest when to use each one. See the “Buprenorphine Induction Strategies” table for a quick overview of dosing specifics.

Standard induction

This is the most common and best-established induction strategy. The approach here is to treat withdrawal symptoms in the first 24 hours and escalate the dose over the next 24–48 hours while targeting cravings. We recommend this approach for most patients since it is relatively fast and the best studied (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Treatment Improvement Protocol 63, revised 2021).

This is the most common and best-established induction strategy. The approach here is to treat withdrawal symptoms in the first 24 hours and escalate the dose over the next 24–48 hours while targeting cravings. We recommend this approach for most patients since it is relatively fast and the best studied (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Treatment Improvement Protocol 63, revised 2021).

Protocol basics

Quantify the severity of opioid withdrawal using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) (www.tinyurl.com/9nmua377). Have the patient stop opioid use and start buprenorphine once they are experiencing moderate withdrawal symptoms as indicated by a COWS score of ≥8–10:

- Day 1: Give 2–4 mg; repeat every hour or so up to 8 mg or until withdrawal subsides

- Day 2: Give the total taken on day 1 first thing in the morning; give additional 4–8 mg doses up to a total of 16 mg or until cravings subside

- Day 3: Give the total taken on day 2 first thing in the morning; give additional 4–8 mg doses up to a total of 24 mg until cravings subside

Today’s street drugs are unpredictable, and street fentanyl can consist of not just fentanyl but also fentanyl derivatives with variable potency and half-lives (see CATR Nov/Dec 2021). You may, therefore, need to adjust your induction approach; for example, you may need to give some patients up to 12 mg of buprenorphine on day 1 to treat withdrawal symptoms.

Benefits: Standard induction is the best-established strategy with the most evidence for getting your patient onto buprenorphine. It is also quite fast, allowing your patient to get up to a full treatment dose of 16–24 mg daily in just a few days. Studies have also shown that standard induction can be completed effectively at home (Lee JD et al, J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(2):226–232). For tips on home induction, see our Q&A with Dr. Capurso in CATR Nov/Dec 2021.

Drawbacks: The biggest drawbacks are the risk of precipitated withdrawal if buprenorphine is given too early and the fact that patients will need to experience some withdrawal symptoms before starting the medication. Also, while quick, standard induction still requires a few days to reach an optimal dose.

When to use: Most patients will do well with standard induction, whether they’re in the clinic, in the emergency department (ED), or at home. They need to be able to tolerate moderate withdrawal symptoms; consider microinduction if they can’t.

Microinduction

Sometimes called “microdosing” (not to be confused with taking small quantities of psychedelics), “low-dose initiation,” or “overlapping,” microinduction was developed to minimize the risk of precipitated withdrawal. It works by introducing buprenorphine while the patient is still on full-agonist opioids, but at doses small enough not to cause much precipitated withdrawal. The dose is raised in small increments so that the body habituates to the presence of both partial and full agonists. Eventually, once the buprenorphine dose is high enough (usually 8–12 mg), the full agonist can be discontinued.

Protocol basics

Patients remain on full opioid agonists, illicit or prescribed, while buprenorphine is slowly increased over a week or so. There are several protocols to choose from, including sublingual, transdermal, and IV options (Jablonsky LA et al, Drug Alcohol Depend 2022;237:109541; Ahmed S et al, Am J Addict 2021;30(4):305–315). Protocols can get complicated, especially in a clinic setting, so these patients are seen daily or every other day until opioid agonists are stopped. Here is a sublingual buprenorphine protocol that you might follow:

- Day 1: Give 0.5 mg daily

- Day 2: Give 0.5 mg BID

- Day 3: Give 1 mg BID

- Day 4: Give 2 mg BID

- Day 5: Give 2 mg TID

- Day 6: Give 2 mg QID

- Day 7: Give 4 mg TID; stop opioid agonists

Benefits: The main benefit of this approach is that it minimizes the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This makes for a more comfortable experience for your patient and might lead to improved treatment adherence and therapeutic rapport.

Drawbacks: Reaching a full treatment dose of 16–24 mg takes seven days or more, essentially leaving the patient undertreated during that time. Additionally, cutting sublingual strips into small pieces can be difficult, and transdermal formulations are more expensive.

When to use: Consider this method when transitioning patients from prescribed opioids like methadone or oxycodone. Microinduction can be useful for patients who have difficulty adhering to the standard protocol, either because of difficulty tolerating withdrawal symptoms or a home environment with easy access to opioids.

Macroinduction

A relatively new approach, macroinduction is designed to get patients on a full dose of buprenorphine as quickly as possible. The approach starts the same as standard induction, with buprenorphine introduced once the patient is in moderate withdrawal; however, after the first 4–8 mg dose, a large single dose of 16–24 mg is given.

Protocol basics

Have the patient stop opioid use and start buprenorphine once they are in moderate withdrawal as indicated by a COWS score ≥8–10 (Herring AA et al, JAMA Network Open 2021;4(7):e2117128):

- Give first dose of 4–8 mg, then wait 30–60 minutes

- As long as there is no precipitated withdrawal, give a single large dose of 16–24 mg for a total of 32 mg

- This dose should be large enough to curb cravings and provide overdose protection for two days

Benefits: This approach gets patients on a full treatment dose of buprenorphine very quickly, usually in a single visit of just a few hours. Despite the large dose, rates of precipitated withdrawal are similar to those seen in standard induction (Herring et al, 2021).

Drawbacks: Of the three approaches, macroinduction has the least amount of evidence and has only been studied rigorously in an ED setting with close medical monitoring. Like the standard approach, macroinduction carries a risk of precipitated withdrawal.

When to use: Consider macroinduction for patients in the ED, especially those who have a high risk of opioid overdose or a history of poor follow-up.

CARLAT VERDICT

The standard buprenorphine induction has the most evidence behind it and should be your go-to. Consider microinduction for patients transition- ing to buprenorphine from prescription opioids or those who have difficulty adhering to the standard approach. Macroinduction can be used for patients in an ED setting, especially if they have a history of poor treatment adherence.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)