Home » How to Treat Tardive Dyskinesia

How to Treat Tardive Dyskinesia

January 13, 2020

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Chris Aiken, MD.

Editor-in-Chief of The Carlat Psychiatry Report. Practicing psychiatrist, Winston-Salem, NC.

Dr. Aiken has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Your patient is a 56-year-old male who recovered from a difficult-to-treat depression 4 years ago after quetiapine was added to his citalopram. As he talks, you notice that his fingers are tapping in a rapid, random pattern and his feet are wiggling. When questioned, he explains, “I just do that when I’m anxious.” Should you stop the antipsychotic, start one of the new medications for tardive dyskinesia, or let it pass?

In 2017, the first FDA-approved medications for tardive dyskinesia (TD) came out: valbenazine (Ingrezza) and deutetrabenazine (Austedo). They aren’t exactly new—both are derivatives of tetrabenazine, which has been used for TD since the 1970s—nor are they the only options for TD. I’ve been involved in TD research and education for 2 decades, and in this article I’ll describe how I manage this insidious condition.

Spontaneous dyskinesias: The other TD

History is important here. Long before the antipsychotics arrived, psychiatrists were describing dyskinesias that looked identical to TD in patients with schizophrenia. Like TD, these “spontaneous dyskinesias” get worse with age, with rates of up to 40% in antipsychotic-naïve patients after age 60. Unlike TD, they get worse during psychotic flare-ups and improve with antipsychotic therapy. Spontaneous dyskinesias are unheard of in mood disorders, although they are seen in schizotypal personality disorder and in close relatives of patients with schizophrenia.

TD in the antipsychotic era

TD was first recognized in the early 1960s. By the 1970s, it had become such a problem that it nearly halted the development of new antipsychotics. Clozapine offered hope. It was, and remains, the only antipsychotic that does not cause TD. Research poured into developing a safer version of clozapine, which is how we got the atypical antipsychotics. Banking on that history, many thought these new drugs would put an end to TD. Some of the early cases of TD on atypicals were even dismissed as spontaneous dyskinesias. That explanation no longer held up when TD started appearing in patients with mood disorders on atypical antipsychotics.

It is now accepted that atypical antipsychotics can cause TD, though some continue to claim that various atypicals (eg, aripiprazole, quetiapine) are free of risk. So far, those arguments have not held up to the data. TD is less common and less severe with atypicals than it is with conventional antipsychotics. The annual incidence of TD is 2.6% on atypical antipsychotics, which translates to a risk of 20% after 10 years. For conventional antipsychotics, that risk is double. However, the elderly have the same annual incidence (5.2%) for both antipsychotic classes (Carbon M et al, World Psychiatry 2018;17(3):330–340; Correll CU and Schenk EM, Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008;21(2):151–156).

Diagnosis of TD

Mild cases of TD can be socially embarrassing, and severe cases can make it painful to eat, speak, or even breathe. Writhing movements of the mouth, eyes, hands, and feet are the most common manifestations. Patients may not notice them or may dismiss them as “nervous habits.” Relatives are often better observers.

When patients are on an antipsychotic, I’ll scan their face, hands, and feet at every visit for abnormal movements. If I see any, I’ll complete the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (www.cqaimh.org/pdf/tool_aims.pdf). It’s recommended to complete an AIMS 1–2 times a year for patients on an antipsychotic, and insurers require it to authorize medications for TD. If you don’t do the full scale, then perform these basic checks:

Management of TD

Step 1: Prevention

Prevention starts by minimizing antipsychotics in patients who are at risk. Among the risk factors, age over 50 is the strongest; others include mood disorders, history of substance abuse, brain injury, diabetes, HIV+, female gender, African American race, and presence of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) (Correll CU et al, J Clin Psych 2017;78(8):1136–1147).

Once patients are on an antipsychotic, try to minimize the dose and duration. Antipsychotic discontinuation may not be possible in schizophrenia, but in mood disorders it is more feasible than industry-supported trials would have us believe (see page 6).

Step 2: Taper off

When the first signs of TD appear, open the discussion about the risks and benefits of the antipsychotic. If discontinuing, go slowly, lowering the dose every 2–4 weeks. The dyskinesias may worsen at first because higher antipsychotic doses can mask TD, and withdrawal dyskinesias may occur for a few months after the antipsychotic is stopped. Although TD can be permanent, 30%–50% of cases resolve with discontinuation.

Step 3: Switch

If discontinuation is not successful, switching may help. Clozapine is the only antipsychotic that does not cause TD, but it has other risks that may preclude its use, especially in mood disorders. Aripiprazole (Abilify) comes in second place, followed by olanzapine (Zyprexa), according to a meta-analysis of 57 head-to-head trials (Carbon M et al, World Psychiatry 2018;17(3):330–340). Surprisingly, quetiapine (Seroquel) had the highest risk in that study, although it is often touted as the preferred antipsychotic for patients with TD. Like clozapine, quetiapine has a low rate of EPS and low levels of D2 occupancy, qualities that—in theory—predict a low risk of TD.

Step 4: VMAT2 inhibitors

When tapering and switching do not work, I’ll attempt to treat the TD, and the FDA-approved VMAT2 inhibitors are first line: valbenazine (Ingrezza) and deutetrabenazine (Austedo). Though released in 2017, their history dates back to the early 1970s when their predecessor tetrabenazine was first used to treat TD. Tetrabenazine never caught on because it had a tendency to cause depression and suicidality, so the molecule was adjusted to reduce that risk. So far, the modifications have worked, and valbenazine and deutetrabenazine have not caused significant depression in trials involving mood and psychotic disorders. Deutetrabenazine, however, does carry a black box warning for depression and suicidality in Huntington’s disease, for which it is also FDA approved.

The VMAT2 inhibitors work by reducing dopamine hypersensitivity, which is one of several mechanisms thought to underlie TD. These medications don’t worsen psychosis. In fact, earlier VMAT2 inhibitors like reserpine have successfully treated psychosis (Remington G et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;32(1):95–99).

In clinical trials, the response rates were 1 in 4 for valbenazine and 1 in 7 for deutetrabenazine (≥ 50% response). However, the trials were not head-to-head studies, so these aren’t fair comparisons. Instead, more practical considerations may favor valbenazine. It is dosed once a day, while deutetrabenazine is dosed twice a day and must be taken with food (Solmi M et al, Drug Des Devel Ther 2018;12:1215–1238).

The VMAT2 inhibitors take 4–6 weeks to work, and if they do work they should be continued as long as the antipsychotic is onboard. Otherwise, the TD tends to return within a month of discontinuation.

Step 5: Second-line agents

Dopaminergic hypersensitivity is not the only mechanism behind TD, and there are second-line agents that address other pathways. The best studied are the glutamate antagonist amantadine, which is FDA approved for dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease, and the neuroprotective herb ginkgo. These are each supported by 3–4 small, randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The others in the table are supported by 1–2 RCTs or, in the case of vitamin E, a mix of positive and negative studies (Lin CC and Ondo WG, J Neurol Sci 2018;389:48–54).

I usually start with amantadine or ginkgo. After that, levetiracetam (Keppra) is one I’ve seen success with. Many of the options in the table address other psychiatric conditions, and it’s those comorbidities that often guide the selection.

One treatment to avoid is benztropine (Cogentin). Although useful for parkinsonian side effects, its anticholinergic effects can make TD worse (Citrome L, J Neurol Sci 2017;383:199–204).

TCPR Verdict: It’s easy for patients and providers to miss the mild presentations of TD that creep up with atypical antipsychotics. It is treatable, but the FDA-approved options may only help 15-25% of patients and are extremely expensive. Off-label treatments like amantadine, ginkgo, and levetiracetam are worth trying when the symptoms are significant and the antipsychotic can’t be removed.

General PsychiatryIn 2017, the first FDA-approved medications for tardive dyskinesia (TD) came out: valbenazine (Ingrezza) and deutetrabenazine (Austedo). They aren’t exactly new—both are derivatives of tetrabenazine, which has been used for TD since the 1970s—nor are they the only options for TD. I’ve been involved in TD research and education for 2 decades, and in this article I’ll describe how I manage this insidious condition.

Spontaneous dyskinesias: The other TD

History is important here. Long before the antipsychotics arrived, psychiatrists were describing dyskinesias that looked identical to TD in patients with schizophrenia. Like TD, these “spontaneous dyskinesias” get worse with age, with rates of up to 40% in antipsychotic-naïve patients after age 60. Unlike TD, they get worse during psychotic flare-ups and improve with antipsychotic therapy. Spontaneous dyskinesias are unheard of in mood disorders, although they are seen in schizotypal personality disorder and in close relatives of patients with schizophrenia.

TD in the antipsychotic era

TD was first recognized in the early 1960s. By the 1970s, it had become such a problem that it nearly halted the development of new antipsychotics. Clozapine offered hope. It was, and remains, the only antipsychotic that does not cause TD. Research poured into developing a safer version of clozapine, which is how we got the atypical antipsychotics. Banking on that history, many thought these new drugs would put an end to TD. Some of the early cases of TD on atypicals were even dismissed as spontaneous dyskinesias. That explanation no longer held up when TD started appearing in patients with mood disorders on atypical antipsychotics.

It is now accepted that atypical antipsychotics can cause TD, though some continue to claim that various atypicals (eg, aripiprazole, quetiapine) are free of risk. So far, those arguments have not held up to the data. TD is less common and less severe with atypicals than it is with conventional antipsychotics. The annual incidence of TD is 2.6% on atypical antipsychotics, which translates to a risk of 20% after 10 years. For conventional antipsychotics, that risk is double. However, the elderly have the same annual incidence (5.2%) for both antipsychotic classes (Carbon M et al, World Psychiatry 2018;17(3):330–340; Correll CU and Schenk EM, Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008;21(2):151–156).

Diagnosis of TD

Mild cases of TD can be socially embarrassing, and severe cases can make it painful to eat, speak, or even breathe. Writhing movements of the mouth, eyes, hands, and feet are the most common manifestations. Patients may not notice them or may dismiss them as “nervous habits.” Relatives are often better observers.

When patients are on an antipsychotic, I’ll scan their face, hands, and feet at every visit for abnormal movements. If I see any, I’ll complete the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (www.cqaimh.org/pdf/tool_aims.pdf). It’s recommended to complete an AIMS 1–2 times a year for patients on an antipsychotic, and insurers require it to authorize medications for TD. If you don’t do the full scale, then perform these basic checks:

- Tongue and face: The tongue is a visible muscle, so you may catch early signs of TD there. Ask the patient to open their mouth wide with their tongue at rest. Does it lie still or squirm and writhe uncontrollably?

- Hands and feet: Have the patient sit with their legs apart and their hands on their knees. Are their feet squirming? Toes flexing up and down? Do their fingers make random tapping motions (“piano player hands”)?

- Reinforcement: If you did not see any movements with steps 1–2, repeat them while having the patient perform a distracting task, such as the patient writing their name in the air. This can “reinforce” or bring out any undetected TD.

Management of TD

Step 1: Prevention

Prevention starts by minimizing antipsychotics in patients who are at risk. Among the risk factors, age over 50 is the strongest; others include mood disorders, history of substance abuse, brain injury, diabetes, HIV+, female gender, African American race, and presence of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) (Correll CU et al, J Clin Psych 2017;78(8):1136–1147).

Once patients are on an antipsychotic, try to minimize the dose and duration. Antipsychotic discontinuation may not be possible in schizophrenia, but in mood disorders it is more feasible than industry-supported trials would have us believe (see page 6).

Step 2: Taper off

When the first signs of TD appear, open the discussion about the risks and benefits of the antipsychotic. If discontinuing, go slowly, lowering the dose every 2–4 weeks. The dyskinesias may worsen at first because higher antipsychotic doses can mask TD, and withdrawal dyskinesias may occur for a few months after the antipsychotic is stopped. Although TD can be permanent, 30%–50% of cases resolve with discontinuation.

Step 3: Switch

If discontinuation is not successful, switching may help. Clozapine is the only antipsychotic that does not cause TD, but it has other risks that may preclude its use, especially in mood disorders. Aripiprazole (Abilify) comes in second place, followed by olanzapine (Zyprexa), according to a meta-analysis of 57 head-to-head trials (Carbon M et al, World Psychiatry 2018;17(3):330–340). Surprisingly, quetiapine (Seroquel) had the highest risk in that study, although it is often touted as the preferred antipsychotic for patients with TD. Like clozapine, quetiapine has a low rate of EPS and low levels of D2 occupancy, qualities that—in theory—predict a low risk of TD.

Step 4: VMAT2 inhibitors

When tapering and switching do not work, I’ll attempt to treat the TD, and the FDA-approved VMAT2 inhibitors are first line: valbenazine (Ingrezza) and deutetrabenazine (Austedo). Though released in 2017, their history dates back to the early 1970s when their predecessor tetrabenazine was first used to treat TD. Tetrabenazine never caught on because it had a tendency to cause depression and suicidality, so the molecule was adjusted to reduce that risk. So far, the modifications have worked, and valbenazine and deutetrabenazine have not caused significant depression in trials involving mood and psychotic disorders. Deutetrabenazine, however, does carry a black box warning for depression and suicidality in Huntington’s disease, for which it is also FDA approved.

The VMAT2 inhibitors work by reducing dopamine hypersensitivity, which is one of several mechanisms thought to underlie TD. These medications don’t worsen psychosis. In fact, earlier VMAT2 inhibitors like reserpine have successfully treated psychosis (Remington G et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;32(1):95–99).

In clinical trials, the response rates were 1 in 4 for valbenazine and 1 in 7 for deutetrabenazine (≥ 50% response). However, the trials were not head-to-head studies, so these aren’t fair comparisons. Instead, more practical considerations may favor valbenazine. It is dosed once a day, while deutetrabenazine is dosed twice a day and must be taken with food (Solmi M et al, Drug Des Devel Ther 2018;12:1215–1238).

The VMAT2 inhibitors take 4–6 weeks to work, and if they do work they should be continued as long as the antipsychotic is onboard. Otherwise, the TD tends to return within a month of discontinuation.

Step 5: Second-line agents

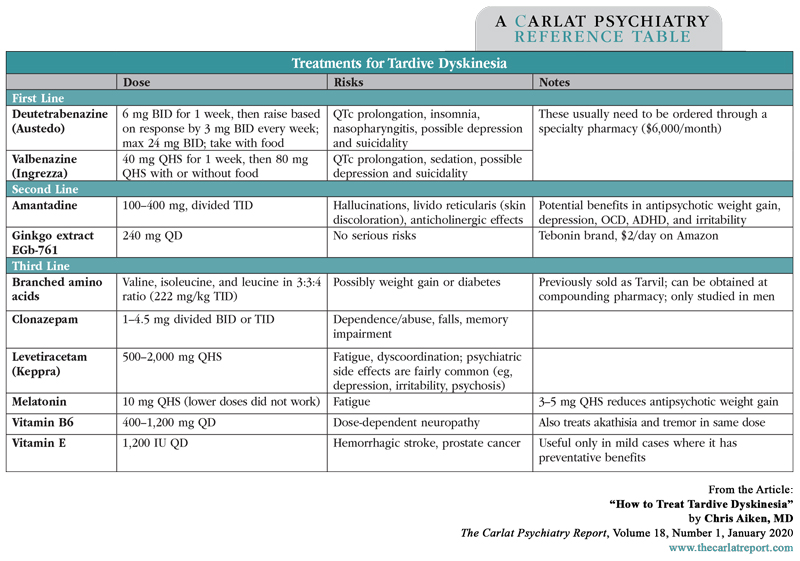

Dopaminergic hypersensitivity is not the only mechanism behind TD, and there are second-line agents that address other pathways. The best studied are the glutamate antagonist amantadine, which is FDA approved for dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease, and the neuroprotective herb ginkgo. These are each supported by 3–4 small, randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The others in the table are supported by 1–2 RCTs or, in the case of vitamin E, a mix of positive and negative studies (Lin CC and Ondo WG, J Neurol Sci 2018;389:48–54).

I usually start with amantadine or ginkgo. After that, levetiracetam (Keppra) is one I’ve seen success with. Many of the options in the table address other psychiatric conditions, and it’s those comorbidities that often guide the selection.

One treatment to avoid is benztropine (Cogentin). Although useful for parkinsonian side effects, its anticholinergic effects can make TD worse (Citrome L, J Neurol Sci 2017;383:199–204).

TCPR Verdict: It’s easy for patients and providers to miss the mild presentations of TD that creep up with atypical antipsychotics. It is treatable, but the FDA-approved options may only help 15-25% of patients and are extremely expensive. Off-label treatments like amantadine, ginkgo, and levetiracetam are worth trying when the symptoms are significant and the antipsychotic can’t be removed.

Table: Treatments for Tardive Dyskinesia

Click To View Full-Size PDF.

KEYWORDS amantadine austedo deutetrabenazine ginkgo ingrezza keppra levetiracetam melatonin psychopharmacology psychopharmacology_tips side-effects tardive-dyskinesia valbenazine vitamin-b6 vitamin-e vmat2-inhibitors

Issue Date: January 13, 2020

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)