Home » Muscle Relaxants: Sedatives Often Under the Radar

Muscle Relaxants: Sedatives Often Under the Radar

June 10, 2020

From The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report

Michael Weaver, MD, FASAM.

Professor and medical director at the Center for Neurobehavioral Research on Addictions at the University of Texas Medical School. Author of Addiction Treatment (Carlat Publishing, 2017).

Dr. Weaver has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

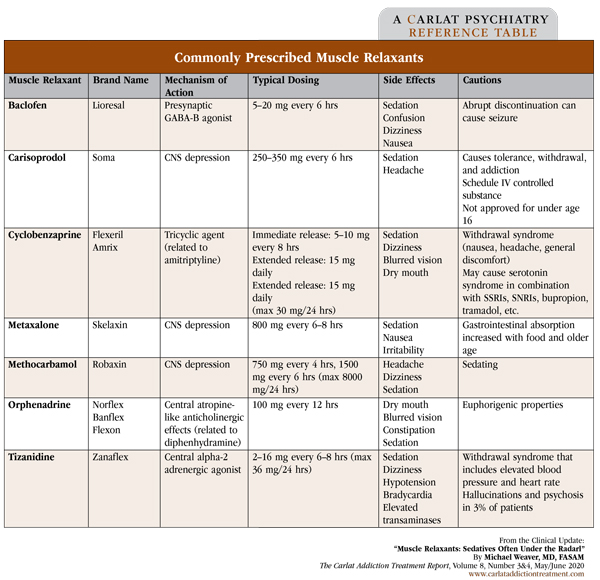

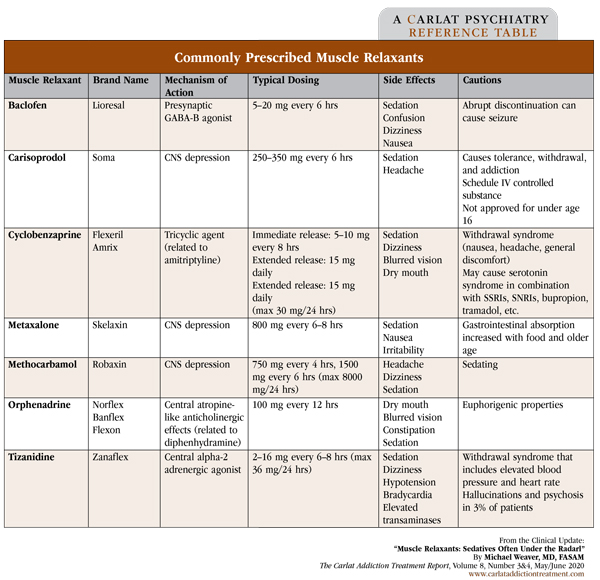

Muscle relaxants are a diverse group of medications with varying mechanisms of action (see Commonly Prescribed Muscle Relaxants table below). They are indicated for short-term treatment (2–3 weeks) of acute, painful muscle spasms, as well as some chronic neurologic conditions associated with spasticity. However, many patients with chronic pain are on them for years, despite little data about long-term safety or efficacy (van Tulder MW et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(2);CD004252). Prescriptions for muscle relaxants are likely on the rise due to recent CDC guidelines for the management of chronic pain that emphasize non-opioid medications (Dowell D et al, MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1–49).

All muscle relaxants may be sedating, which poses increased risks when combined with other medications for chronic pain, psychiatric disorders, or addiction treatment. Different muscle relaxants are thought to have similar efficacy, so choose one based on side effects, drug interactions, and abuse potential (Chou R et al, J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28(2):140–175).

Baclofen, tizanidine, and cyclobenzaprine cause withdrawal syndromes if stopped abruptly, so tapering is recommended. Tizanidine may lower blood pressure, so it should be used with caution in patients at risk for hypotension or bradycardia due to other medical conditions or medications. Keep in mind, too, that baclofen may be prescribed for the management of alcohol use disorder (see Research Update on page 9).

Carisoprodol (Soma) is especially risky for patients with substance use disorders or who use sedatives—whether therapeutically or recreationally. Many prescribers are unaware that the liver metabolizes carisoprodol to meprobamate, which used to be marketed as Miltown or Equanil. Meprobamate has sedative effects similar to barbiturates and can cause respiratory depression, euphoria, and anxiolysis. Since carisoprodol is not an obvious sedative, it is often sought by patients seeking to achieve a high or to manage anxiety, and may end up on the black market. It is classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance, so it is often tracked by state prescription monitoring programs. Nearly all cases of addiction to muscle relaxants are due to carisoprodol, although cyclobenzaprine has also been associated with misuse.

Ten percent of patients prescribed opioids are also prescribed muscle relaxants (Mosher HJ et al, Pain Med 2017;19(4):788–792). Combining opioids, benzodiazepines, and carisoprodol is reported to potentiate euphoria and has been called the “Holy Trinity”; this combination is associated with respiratory depression and increases the risk of opioid overdose (we recommend watching the Netflix documentary series, The Pharmacist, for an eye-opening account of a pill mill that specialized in prescribing the Holy Trinity to people with opioid use disorder). Short-term use, lower opioid doses, and cyclobenzaprine are associated with less risk of overdose.

CATR Verdict: Clinicians may prescribe muscle relaxants on a short-term basis (2–3 weeks) for acute spasticity and muscle pain, but evidence for efficacy in chronic pain management is lacking. Educate patients about the risks of sedation and overdose in combination with other sedating substances. Cyclobenzaprine or tizanidine appear safer, but tapering is recommended after longer-term use. Avoid carisoprodol due to its potential for misuse and look out for it on prescription drug monitoring programs.

Table: Commonly Prescribed Muscle Relaxants

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Addiction TreatmentAll muscle relaxants may be sedating, which poses increased risks when combined with other medications for chronic pain, psychiatric disorders, or addiction treatment. Different muscle relaxants are thought to have similar efficacy, so choose one based on side effects, drug interactions, and abuse potential (Chou R et al, J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28(2):140–175).

Baclofen, tizanidine, and cyclobenzaprine cause withdrawal syndromes if stopped abruptly, so tapering is recommended. Tizanidine may lower blood pressure, so it should be used with caution in patients at risk for hypotension or bradycardia due to other medical conditions or medications. Keep in mind, too, that baclofen may be prescribed for the management of alcohol use disorder (see Research Update on page 9).

Carisoprodol (Soma) is especially risky for patients with substance use disorders or who use sedatives—whether therapeutically or recreationally. Many prescribers are unaware that the liver metabolizes carisoprodol to meprobamate, which used to be marketed as Miltown or Equanil. Meprobamate has sedative effects similar to barbiturates and can cause respiratory depression, euphoria, and anxiolysis. Since carisoprodol is not an obvious sedative, it is often sought by patients seeking to achieve a high or to manage anxiety, and may end up on the black market. It is classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance, so it is often tracked by state prescription monitoring programs. Nearly all cases of addiction to muscle relaxants are due to carisoprodol, although cyclobenzaprine has also been associated with misuse.

Ten percent of patients prescribed opioids are also prescribed muscle relaxants (Mosher HJ et al, Pain Med 2017;19(4):788–792). Combining opioids, benzodiazepines, and carisoprodol is reported to potentiate euphoria and has been called the “Holy Trinity”; this combination is associated with respiratory depression and increases the risk of opioid overdose (we recommend watching the Netflix documentary series, The Pharmacist, for an eye-opening account of a pill mill that specialized in prescribing the Holy Trinity to people with opioid use disorder). Short-term use, lower opioid doses, and cyclobenzaprine are associated with less risk of overdose.

CATR Verdict: Clinicians may prescribe muscle relaxants on a short-term basis (2–3 weeks) for acute spasticity and muscle pain, but evidence for efficacy in chronic pain management is lacking. Educate patients about the risks of sedation and overdose in combination with other sedating substances. Cyclobenzaprine or tizanidine appear safer, but tapering is recommended after longer-term use. Avoid carisoprodol due to its potential for misuse and look out for it on prescription drug monitoring programs.

Table: Commonly Prescribed Muscle Relaxants

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

KEYWORDS clinical-practice deprescribing opioids pain pharmacology polypharmacy prescribing-patterns risk_management

Issue Date: June 10, 2020

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)