Home » Mood, Cognition, and Metabolic Health

Mood, Cognition, and Metabolic Health

March 26, 2021

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Rodrigo Barbachan Mansur, MD

Rodrigo Barbachan Mansur, MD

Assistant Professor, Division of Brain and Therapeutics, University of Toronto. Dr. Mansur has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: Your research has explored how metabolic disorders can impair mood and cognition. Can you give us an overview of that topic?

Dr. Mansur: Yes. There is a direct association between metabolic health and both mood and cognitive outcomes. All of the components of the metabolic syndrome—obesity, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension—increase the risk that someone will develop depression and/or cognitive problems over time. Diabetes is one of the most well-recognized risk factors for late-life cognitive decline. People with type II diabetes have a high risk of cognitive impairment that may eventually progress to dementia, and that risk is independent of depression (Xue M et al, Ageing Res Rev 2019,55:100944).

TCPR: What’s the mechanism behind those links?

Dr. Mansur: That is complex and not fully understood, but there are several possible pathways. There is:

In people with diabetes, we see evidence of insulin resistance in the brain, and this may mediate some of the association between metabolic health and psychiatric disorders.

TCPR: Now wait—in medical school I was taught the brain didn’t rely on insulin to absorb glucose.

Dr. Mansur: The brain relies less on insulin than the muscle cells or the liver to absorb glucose. But what we’re seeing in diabetes is dysfunctional insulin signaling in the brain. Insulin mediates feeding in the brain, but its role goes beyond that. There are insulin receptors in the prefrontal cortex, the nucleus accumbens, and the ventral striatum areas where it plays a role in reward behaviors. And there is evidence now from both preclinical and clinical work that insulin signaling modulates how those regions are activated, and that modulation leads to behavioral changes like anhedonia. We have evidence that that’s the case in obese populations, and we have done some work in depression as well (Hamer JA et al, Exp Neurol 2019;315:1–8).

TCPR: How is vascular health involved in these mood and cognitive changes?

Dr. Mansur: Even in the early stages of mental illness, our patients already have some level of cardiovascular dysfunction. And vascular health is one of the leading causes of the increased mortality we see in individuals with mental health problems. The number one cause of death in depression and bipolar disorder is cardiovascular disease. But vascular disease is not the only pathway here. Even when microvascular disease is absent, metabolic factors affect mood and cognition.

TCPR: There’s a new class of diabetes medications called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and your group is exploring their role in mood disorders. What have you found?

Dr. Mansur: We have done a pilot study with liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda). It was a small, open-label study of 19 patients who had cognitive problems along with depression or bipolar disorder, but no diabetes. Liraglutide (1.8 mg/day) brought about cognitive improvements after 4 weeks (Mansur RB et al, J Affect Disord 2017;207:114–120). We are now going to the next step: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with semaglutide (Rybelsus). Semaglutide is in the same class as liraglutide but has the advantage of oral delivery, while liraglutide is an injection. Outside of the mood disorder population, there are larger studies showing benefits in memory and cognition when GLP-1 receptor agonists are used to treat obesity, prediabetes, and diabetes (Cukierman-Yaffe T et al, Lancet Neurol 2020;19(7):582–590).

TCPR: There is also a study of liraglutide for antipsychotic-associated weight gain (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728). Do you think it’s ready for use there?

Dr. Mansur: I prefer metformin over liraglutide for weight gain on antipsychotics, because the evidence for metformin is more solid—it’s replicated, and there are more than a few meta-analyses. Metformin not only improves weight, but also has positive effects on metabolic health, reducing insulin resistance, HbA1c, and even dyslipidemia (Jiang WL et al, Transl Psychiatry 2020;10(1):117). Metformin is relatively simple to use for a psychiatrist. I usually start with 1,000 mg daily, with food. A few studies have gone to 1,500 or 2,000 mg daily, which is also safe and effective. The main risk is hypoglycemia, but with metformin that risk is quite low. I do use liraglutide for metabolic problems on antipsychotics, but only if the problem is significant and doesn’t respond to metformin.

TCPR: How do you dose liraglutide?

Dr. Mansur: Liraglutide needs to be titrated slowly because of the risk of nausea. Start with a 0.6 mg subcutaneous injection daily for 1 week and then increase to 1.2 mg daily, which is the therapeutic dose. Then if the patient responds and tolerates it, you can titrate upwards, toward a maximum of 3 mg a day.

TCPR: Outside of nausea, are there other risks with liraglutide?

Dr. Mansur: Liraglutide has a very favorable safety profile. For example, it does not tend to cause hypoglycemia, even in normal glycemic populations. Although it’s an injection, it’s a very thin needle, so patients tend to tolerate it well without significant pain or skin problems. There were some animal studies indicating that GLP-1 receptor agonists increase the risk of pancreatic cancer, but nothing that was replicated and nothing that was shown in human populations.

TCPR: Does your approach to mood disorders differ when you are treating a patient who has both diabetes and depression?

Dr. Mansur: We need to be mindful of the detrimental effects of the metabolic comorbidities and address them directly. Most psychiatrists are probably not comfortable prescribing antidiabetic medications, but there are other ways to address metabolic health that do not involve these medications. Physical exercise, diet, and sleep hygiene play a role in metabolic health, and in mental health as well. Shift work is another factor. If you take healthy volunteers and put them on shift work, within a few weeks they start developing insulin resistance.

TCPR: Which diet do you recommend for people with depression and metabolic problems?

Dr. Mansur: There is no consensus on the best diet for depression. The Mediterranean diet has the best evidence for mood, and it’s one of the easiest to apply. Patients often ask about the ketogenic diet, but this involves some major changes in dietary patterns that are difficult to maintain. Right now we have good evidence for the ketogenic diet in epilepsy. There is a case series in schizophrenia, and our group is launching a trial of it in depression (Sarnyai Z et al, Curr Opin Psychiatry 2019;32(5):394–401). The ketogenic diet has the potential to improve metabolic and inflammatory pathways, but it also has risks. It requires increased fat intake, and there are even some case reports of mania on it.

TCPR: I’ve seen some papers suggesting that antidepressants improve outcomes in diabetes, and others suggesting the opposite. What’s your take?

Dr. Mansur: That research is quite challenging because there are a lot of confounders there. I’m not convinced that antidepressants have a strong effect—either positive or negative—on metabolic health. On the one hand, there is evidence that antidepressants have protective effects on metabolic health. On the other hand, there is some preclinical evidence showing that they can have a negative effect on pancreatic beta cell function. I’m not convinced that there’s a large effect there; otherwise we would see it clinically, such as more intense variations in weight following trials with antidepressants. That can happen, but it’s not very common overall. When treating someone with diabetes and depression, I would avoid antidepressants that are more strongly associated with weight gain, like mirtazapine, trazodone, and paroxetine.

TCPR: Coming from the other side, do we know enough about the mood benefits of antidiabetic agents to guide treatment in people with diabetes and depression? I’m thinking of the cognitive benefits you saw with liraglutide, and emerging data on antidepressant effects with metformin (Abdallah MS et al, Neurotherapeutics 2020;17(4):1897–1906).

Dr. Mansur: Those are intriguing research findings, but I don’t think they are ready for clinical practice. I’d say the same thing about statins in depression. There are some clinical studies suggesting certain statins may augment antidepressants, but the data are small and mostly come from the same research group. We need more independent replication there.

TCPR: I understand there’s a new software package to measure cognition that you helped develop.

Dr. Mansur: Yes. THINC-it is a free computerized cognitive test that we validated in depression and bipolar disorders (https://thinc.progress.im/en). By “validated,” I mean that it compared well to traditional pen-and-paper tests and was sensitive enough to detect meaningful changes over time. It is quick and can be done on a tablet or laptop (McIntyre RS et al, Front Psychiatry 2020;11:546).

TCPR: What does the test contain?

Dr. Mansur: THINC-it has four cognitive tests that are based on well-established neuropsychiatric tests for attention, working memory, and executive function. It graphs the patient’s results against the normal population and tracks progress over time.

TCPR: How do you use THINC-it in practice?

Dr. Mansur: Often when treating patients with depression, their mood improves but their cognitive function doesn’t, which makes it hard for them to return to work because it’s these cognitive symptoms that play a key role in functional outcomes. So it’s very important to monitor cognition as you change medications or add behavioral interventions. On that note, the results can help motivate patients to stick with behavioral interventions for cognition, such as diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene.

TCPR: What are some medications that have potential cognitive benefits in depression?

Dr. Mansur: We have vortioxetine, which mainly showed improvements on the digit symbol substitution test that is part of THINC-it. (Editor’s note: THINC-it was sponsored by the manufacturer of vortioxetine, Lundbeck. Dr. Mansur has contributed to Lundbeck-sponsored projects but has not directly received funding from Lundbeck.) Duloxetine and bupropion also have some cognitive benefits, and just treating depression alone can improve cognition (Blumberg MJ et al, J Clin Psych 2020;81(4):19r13200). There’s also the psychostimulants and the modafinils. Modafinil’s cognitive benefits in mood disorders are actually more robust than those of traditional psychostimulants like methylphenidate. Metabolic health is important here as well. Treatments that target metabolic health may also help cognition.

TCPR: Is THINC-it useful in other psychiatric disorders, like schizophrenia, ADHD, or dementia?

Dr. Mansur: It might be harder to translate the test to dementia because it involves different domains. But for ADHD, for anxiety, for psychosis, I see no reason why it wouldn’t be a good fit. Cognitive symptoms overlap across different conditions—not only in psychiatry, but also from the medical side. Diabetes and obesity have independent effects on cognitive function.

TCPR: So THINC-it won’t help us differentiate mood disorders from ADHD.

Dr. Mansur: No. It is not a diagnostic test. ADHD and depression involve similar cognitive symptoms, so it is very challenging to distinguish them in practice. That distinction has to be based on history, course of symptoms over time, and response to treatment.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Mansur.

To learn more, listen to our 4/12/21 podcast, “Mood, Metabolism, and Cognition: An Interview With Rodrigo Mansur.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

To learn more, listen to our 4/12/21 podcast, “Mood, Metabolism, and Cognition: An Interview With Rodrigo Mansur.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

General PsychiatryDr. Mansur: Yes. There is a direct association between metabolic health and both mood and cognitive outcomes. All of the components of the metabolic syndrome—obesity, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension—increase the risk that someone will develop depression and/or cognitive problems over time. Diabetes is one of the most well-recognized risk factors for late-life cognitive decline. People with type II diabetes have a high risk of cognitive impairment that may eventually progress to dementia, and that risk is independent of depression (Xue M et al, Ageing Res Rev 2019,55:100944).

TCPR: What’s the mechanism behind those links?

Dr. Mansur: That is complex and not fully understood, but there are several possible pathways. There is:

- The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates the stress response

- Vascular health

- Inflammation

- Insulin resistance

In people with diabetes, we see evidence of insulin resistance in the brain, and this may mediate some of the association between metabolic health and psychiatric disorders.

TCPR: Now wait—in medical school I was taught the brain didn’t rely on insulin to absorb glucose.

Dr. Mansur: The brain relies less on insulin than the muscle cells or the liver to absorb glucose. But what we’re seeing in diabetes is dysfunctional insulin signaling in the brain. Insulin mediates feeding in the brain, but its role goes beyond that. There are insulin receptors in the prefrontal cortex, the nucleus accumbens, and the ventral striatum areas where it plays a role in reward behaviors. And there is evidence now from both preclinical and clinical work that insulin signaling modulates how those regions are activated, and that modulation leads to behavioral changes like anhedonia. We have evidence that that’s the case in obese populations, and we have done some work in depression as well (Hamer JA et al, Exp Neurol 2019;315:1–8).

TCPR: How is vascular health involved in these mood and cognitive changes?

Dr. Mansur: Even in the early stages of mental illness, our patients already have some level of cardiovascular dysfunction. And vascular health is one of the leading causes of the increased mortality we see in individuals with mental health problems. The number one cause of death in depression and bipolar disorder is cardiovascular disease. But vascular disease is not the only pathway here. Even when microvascular disease is absent, metabolic factors affect mood and cognition.

Therapeutic advances

TCPR: There’s a new class of diabetes medications called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and your group is exploring their role in mood disorders. What have you found?

Dr. Mansur: We have done a pilot study with liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda). It was a small, open-label study of 19 patients who had cognitive problems along with depression or bipolar disorder, but no diabetes. Liraglutide (1.8 mg/day) brought about cognitive improvements after 4 weeks (Mansur RB et al, J Affect Disord 2017;207:114–120). We are now going to the next step: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with semaglutide (Rybelsus). Semaglutide is in the same class as liraglutide but has the advantage of oral delivery, while liraglutide is an injection. Outside of the mood disorder population, there are larger studies showing benefits in memory and cognition when GLP-1 receptor agonists are used to treat obesity, prediabetes, and diabetes (Cukierman-Yaffe T et al, Lancet Neurol 2020;19(7):582–590).

TCPR: There is also a study of liraglutide for antipsychotic-associated weight gain (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728). Do you think it’s ready for use there?

Dr. Mansur: I prefer metformin over liraglutide for weight gain on antipsychotics, because the evidence for metformin is more solid—it’s replicated, and there are more than a few meta-analyses. Metformin not only improves weight, but also has positive effects on metabolic health, reducing insulin resistance, HbA1c, and even dyslipidemia (Jiang WL et al, Transl Psychiatry 2020;10(1):117). Metformin is relatively simple to use for a psychiatrist. I usually start with 1,000 mg daily, with food. A few studies have gone to 1,500 or 2,000 mg daily, which is also safe and effective. The main risk is hypoglycemia, but with metformin that risk is quite low. I do use liraglutide for metabolic problems on antipsychotics, but only if the problem is significant and doesn’t respond to metformin.

TCPR: How do you dose liraglutide?

Dr. Mansur: Liraglutide needs to be titrated slowly because of the risk of nausea. Start with a 0.6 mg subcutaneous injection daily for 1 week and then increase to 1.2 mg daily, which is the therapeutic dose. Then if the patient responds and tolerates it, you can titrate upwards, toward a maximum of 3 mg a day.

TCPR: Outside of nausea, are there other risks with liraglutide?

Dr. Mansur: Liraglutide has a very favorable safety profile. For example, it does not tend to cause hypoglycemia, even in normal glycemic populations. Although it’s an injection, it’s a very thin needle, so patients tend to tolerate it well without significant pain or skin problems. There were some animal studies indicating that GLP-1 receptor agonists increase the risk of pancreatic cancer, but nothing that was replicated and nothing that was shown in human populations.

Treating depression and diabetes

TCPR: Does your approach to mood disorders differ when you are treating a patient who has both diabetes and depression?

Dr. Mansur: We need to be mindful of the detrimental effects of the metabolic comorbidities and address them directly. Most psychiatrists are probably not comfortable prescribing antidiabetic medications, but there are other ways to address metabolic health that do not involve these medications. Physical exercise, diet, and sleep hygiene play a role in metabolic health, and in mental health as well. Shift work is another factor. If you take healthy volunteers and put them on shift work, within a few weeks they start developing insulin resistance.

TCPR: Which diet do you recommend for people with depression and metabolic problems?

Dr. Mansur: There is no consensus on the best diet for depression. The Mediterranean diet has the best evidence for mood, and it’s one of the easiest to apply. Patients often ask about the ketogenic diet, but this involves some major changes in dietary patterns that are difficult to maintain. Right now we have good evidence for the ketogenic diet in epilepsy. There is a case series in schizophrenia, and our group is launching a trial of it in depression (Sarnyai Z et al, Curr Opin Psychiatry 2019;32(5):394–401). The ketogenic diet has the potential to improve metabolic and inflammatory pathways, but it also has risks. It requires increased fat intake, and there are even some case reports of mania on it.

TCPR: I’ve seen some papers suggesting that antidepressants improve outcomes in diabetes, and others suggesting the opposite. What’s your take?

Dr. Mansur: That research is quite challenging because there are a lot of confounders there. I’m not convinced that antidepressants have a strong effect—either positive or negative—on metabolic health. On the one hand, there is evidence that antidepressants have protective effects on metabolic health. On the other hand, there is some preclinical evidence showing that they can have a negative effect on pancreatic beta cell function. I’m not convinced that there’s a large effect there; otherwise we would see it clinically, such as more intense variations in weight following trials with antidepressants. That can happen, but it’s not very common overall. When treating someone with diabetes and depression, I would avoid antidepressants that are more strongly associated with weight gain, like mirtazapine, trazodone, and paroxetine.

TCPR: Coming from the other side, do we know enough about the mood benefits of antidiabetic agents to guide treatment in people with diabetes and depression? I’m thinking of the cognitive benefits you saw with liraglutide, and emerging data on antidepressant effects with metformin (Abdallah MS et al, Neurotherapeutics 2020;17(4):1897–1906).

Dr. Mansur: Those are intriguing research findings, but I don’t think they are ready for clinical practice. I’d say the same thing about statins in depression. There are some clinical studies suggesting certain statins may augment antidepressants, but the data are small and mostly come from the same research group. We need more independent replication there.

A new app for cognition

TCPR: I understand there’s a new software package to measure cognition that you helped develop.

Dr. Mansur: Yes. THINC-it is a free computerized cognitive test that we validated in depression and bipolar disorders (https://thinc.progress.im/en). By “validated,” I mean that it compared well to traditional pen-and-paper tests and was sensitive enough to detect meaningful changes over time. It is quick and can be done on a tablet or laptop (McIntyre RS et al, Front Psychiatry 2020;11:546).

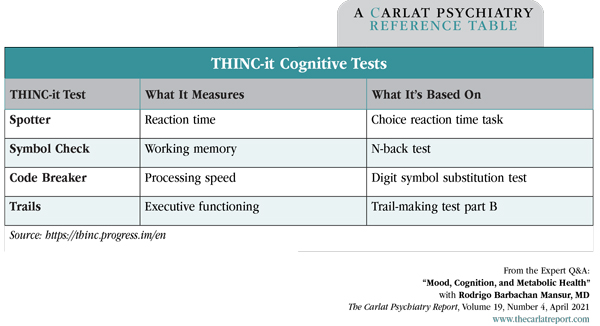

TCPR: What does the test contain?

Dr. Mansur: THINC-it has four cognitive tests that are based on well-established neuropsychiatric tests for attention, working memory, and executive function. It graphs the patient’s results against the normal population and tracks progress over time.

Table: THINC-it Cognitive Tests

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

TCPR: How do you use THINC-it in practice?

Dr. Mansur: Often when treating patients with depression, their mood improves but their cognitive function doesn’t, which makes it hard for them to return to work because it’s these cognitive symptoms that play a key role in functional outcomes. So it’s very important to monitor cognition as you change medications or add behavioral interventions. On that note, the results can help motivate patients to stick with behavioral interventions for cognition, such as diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene.

TCPR: What are some medications that have potential cognitive benefits in depression?

Dr. Mansur: We have vortioxetine, which mainly showed improvements on the digit symbol substitution test that is part of THINC-it. (Editor’s note: THINC-it was sponsored by the manufacturer of vortioxetine, Lundbeck. Dr. Mansur has contributed to Lundbeck-sponsored projects but has not directly received funding from Lundbeck.) Duloxetine and bupropion also have some cognitive benefits, and just treating depression alone can improve cognition (Blumberg MJ et al, J Clin Psych 2020;81(4):19r13200). There’s also the psychostimulants and the modafinils. Modafinil’s cognitive benefits in mood disorders are actually more robust than those of traditional psychostimulants like methylphenidate. Metabolic health is important here as well. Treatments that target metabolic health may also help cognition.

TCPR: Is THINC-it useful in other psychiatric disorders, like schizophrenia, ADHD, or dementia?

Dr. Mansur: It might be harder to translate the test to dementia because it involves different domains. But for ADHD, for anxiety, for psychosis, I see no reason why it wouldn’t be a good fit. Cognitive symptoms overlap across different conditions—not only in psychiatry, but also from the medical side. Diabetes and obesity have independent effects on cognitive function.

TCPR: So THINC-it won’t help us differentiate mood disorders from ADHD.

Dr. Mansur: No. It is not a diagnostic test. ADHD and depression involve similar cognitive symptoms, so it is very challenging to distinguish them in practice. That distinction has to be based on history, course of symptoms over time, and response to treatment.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Mansur.

Issue Date: March 26, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)