Home » Management of Opioid Withdrawal in the Emergency Setting

Management of Opioid Withdrawal in the Emergency Setting

March 19, 2021

From The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report

Rehan Aziz, MD.

Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Dr. Aziz has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Opioid withdrawal is being seen more frequently in emergency settings. From 2005 to 2014, it is estimated that the rate of US emergency department (ED) visits due to opioids doubled from 89.1 per 100,000 people to 177.7 per 100,000 (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, www.tinyurl.com/2xr8hp8h). For many patients, the ED is their only contact with the health care system. Successful medically monitored withdrawal management can facilitate patient engagement in treatment, or at the very least avoid alienating them from future medical care. This article will help you assess and manage opioid withdrawal in emergency settings and advocate for your patients’ care if they end up in the ED.

Assessment

Most patients in opioid withdrawal will tell you right off the bat that they are withdrawing, or that they are “dope sick.” Nonetheless, you should document the signs and symptoms of withdrawal (see below) as treatment decisions depend on its severity and time course.

Signs and Symptoms of Opioid Withdrawal

For short-acting opioids (eg, heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone), withdrawal typically begins 6 to 12 hours after the last dose, peaks within 24 to 48 hours, and can persist for several days. For those on longer-acting opioids like methadone or the partial agonist buprenorphine, the withdrawal symptoms probably won’t be as intense, but the timeline will be significantly extended; in these cases, withdrawal starts a day or two after cessation, has a peak of a week or more, and can persist for as long as 2 to 3 weeks. Of course, withdrawal is precipitated almost immediately after administration of an opioid blocker like naloxone—which applies to many patients who end up in the ED.

The most common opioid withdrawal scale is the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). It grades withdrawal severity from 0 to 36 points on measures including pulse, pupillary size, restlessness, and yawning (Wesson DR and Ling W, J Psychoactive Drugs 2003;35(2):253–259); it is similar to the CIWA-Ar scale used for alcohol withdrawal, though the latter does not include vital signs. COWS is becoming more popular as many stable patients are sent home from the ED and instructed to monitor for their own opioid withdrawal symptoms.

Treatment strategies

The best way to treat opioid withdrawal in the ED is to use an opioid agonist or partial agonist as a bridge to long-term outpatient treatment. You can use buprenorphine/naloxone (bup/nx) or methadone, though bup/nx is usually preferred due to its less stringent regulations. Note that ED providers may use buprenorphine to manage withdrawal symptoms without additional waivers or specific training. See table on page 6 for dosing and treatment recommendations. For info on billing for the initiation of medication for ED treatment of OUD, including assessment, referral to ongoing care, and arranging access to supportive services, see: www.tinyurl.com/z57tshz4

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is an opioid receptor partial agonist. It causes minimal euphoria, and there’s a ceiling effect on both sedation and respiratory depression. Because bup/nx has very high opioid receptor affinity, it can precipitate withdrawal in patients who are opioid-intoxicated or in very early withdrawal. Thus, don’t start bup/nx until the COWS score has reached at least 8. Talk to patients about their preferences—most will have prior bup/nx experience and will have strong opinions on when it’s safe for them to start it in order to avoid withdrawal.

In terms of dosing, I recommend starting with 2–4 mg followed by an additional 2–4 mg dose 2 hours later; most patients will achieve substantive relief by the time they receive 8 mg (Herring AA et al, Ann Emerg Med 2019;73:481–487). The FDA recommends that patients receive no more than 8 mg in the first day after last use, 16 mg on the second day, and then up to 24 mg daily thereafter. However, patients may need more than 8 mg in those first 24 hours. The most important goal is to keep them comfortable and engaged in treatment.

Methadone

Use methadone only if bup/nx isn’t available or in patients who are withdrawing from methadone, especially if they plan to return to methadone treatment. Start with either 10 mg intramuscularly (in patients who are vomiting) or 20 mg orally. Titrate very slowly, especially if the patient has not been on methadone before. These doses are enough to significantly reduce COWS scores without causing significant sedation or respiratory depression—both of which are concerns at higher doses. If the patient is enrolled in a methadone maintenance clinic, call the clinic to confirm what their dosage was, when the patient last received a dose, and if they are able to return for dosing soon. Some patients may have to wait to return to a clinic—or even find another clinic—because of extended no-shows or violating program rules.

Clonidine and adjunctive symptomatic medications

In some settings, buprenorphine or methadone may not be available or a patient may not agree to take them. In these cases, treat withdrawal based on your patient’s symptoms (see table on page 6 for some commonly used agents). Overall, this strategy doesn’t work as well, but it’s something to consider—especially for patients intending to initiate long-acting injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol), which requires first being opioid free for 7 to 10 days.

Transitioning from detoxification to treatment

Encourage patients to begin outpatient opioid use disorder treatment after detox, and ensure they have a reliable follow-up plan. If your ED has access to a recovery coach in house, arrange a meeting before discharge. If your patient declines a referral, stress that their risk for relapse and overdose will be high. Those who decline further treatment should have their medications tapered off prior to discharge. In contrast, patients who agree to treatment can have their dose gradually increased up to standard outpatient dosages (30–40 mg for methadone and 8–24 mg for bup/nx). For bup/nx, provide a prescription for a week or so, if possible, to cover them until they can see a certified outpatient provider. Supply a naloxone prescription or kit before they leave the ED, too.

Basic harm reduction strategies

Before your patients leave your care, don’t forget to mention harm reduction strategies. An ED visit allows you to review the following with your patients, especially if they receive the majority of their care emergently or decline follow-up treatment:

CATR Verdict: The ED is a primary point of medical contact for individuals with unhealthy opioid use. Treat their withdrawal, preferably with bup/nx or methadone, and refer to treatment if willing. Don’t forget to exercise harm reduction practices such as offering appropriate infection screening, vaccines, PrEP, and a naloxone prescription. Finally, provide a list of community substance use resources and make a warm handoff if you can.

Addiction TreatmentAssessment

Most patients in opioid withdrawal will tell you right off the bat that they are withdrawing, or that they are “dope sick.” Nonetheless, you should document the signs and symptoms of withdrawal (see below) as treatment decisions depend on its severity and time course.

Signs and Symptoms of Opioid Withdrawal

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

|

Gastrointestinal Abdominal cramps Diarrhea Nausea Vomiting |

Vital signs Increased heart rate Increased blood pressure |

|

Head and neck Runny nose Tearing Yawning |

Gastrointestinal Increased bowel sounds |

|

Musculoskeletal Bone pain Joint pain Muscle cramps |

Ophthalmologic Dilated pupils Tearing |

|

Neuropsychiatric Anxiety Insomnia Low mood Restlessness Tremors |

Skin Goosebumps Sweating |

For short-acting opioids (eg, heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone), withdrawal typically begins 6 to 12 hours after the last dose, peaks within 24 to 48 hours, and can persist for several days. For those on longer-acting opioids like methadone or the partial agonist buprenorphine, the withdrawal symptoms probably won’t be as intense, but the timeline will be significantly extended; in these cases, withdrawal starts a day or two after cessation, has a peak of a week or more, and can persist for as long as 2 to 3 weeks. Of course, withdrawal is precipitated almost immediately after administration of an opioid blocker like naloxone—which applies to many patients who end up in the ED.

The most common opioid withdrawal scale is the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). It grades withdrawal severity from 0 to 36 points on measures including pulse, pupillary size, restlessness, and yawning (Wesson DR and Ling W, J Psychoactive Drugs 2003;35(2):253–259); it is similar to the CIWA-Ar scale used for alcohol withdrawal, though the latter does not include vital signs. COWS is becoming more popular as many stable patients are sent home from the ED and instructed to monitor for their own opioid withdrawal symptoms.

Treatment strategies

The best way to treat opioid withdrawal in the ED is to use an opioid agonist or partial agonist as a bridge to long-term outpatient treatment. You can use buprenorphine/naloxone (bup/nx) or methadone, though bup/nx is usually preferred due to its less stringent regulations. Note that ED providers may use buprenorphine to manage withdrawal symptoms without additional waivers or specific training. See table on page 6 for dosing and treatment recommendations. For info on billing for the initiation of medication for ED treatment of OUD, including assessment, referral to ongoing care, and arranging access to supportive services, see: www.tinyurl.com/z57tshz4

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is an opioid receptor partial agonist. It causes minimal euphoria, and there’s a ceiling effect on both sedation and respiratory depression. Because bup/nx has very high opioid receptor affinity, it can precipitate withdrawal in patients who are opioid-intoxicated or in very early withdrawal. Thus, don’t start bup/nx until the COWS score has reached at least 8. Talk to patients about their preferences—most will have prior bup/nx experience and will have strong opinions on when it’s safe for them to start it in order to avoid withdrawal.

In terms of dosing, I recommend starting with 2–4 mg followed by an additional 2–4 mg dose 2 hours later; most patients will achieve substantive relief by the time they receive 8 mg (Herring AA et al, Ann Emerg Med 2019;73:481–487). The FDA recommends that patients receive no more than 8 mg in the first day after last use, 16 mg on the second day, and then up to 24 mg daily thereafter. However, patients may need more than 8 mg in those first 24 hours. The most important goal is to keep them comfortable and engaged in treatment.

Methadone

Use methadone only if bup/nx isn’t available or in patients who are withdrawing from methadone, especially if they plan to return to methadone treatment. Start with either 10 mg intramuscularly (in patients who are vomiting) or 20 mg orally. Titrate very slowly, especially if the patient has not been on methadone before. These doses are enough to significantly reduce COWS scores without causing significant sedation or respiratory depression—both of which are concerns at higher doses. If the patient is enrolled in a methadone maintenance clinic, call the clinic to confirm what their dosage was, when the patient last received a dose, and if they are able to return for dosing soon. Some patients may have to wait to return to a clinic—or even find another clinic—because of extended no-shows or violating program rules.

Clonidine and adjunctive symptomatic medications

In some settings, buprenorphine or methadone may not be available or a patient may not agree to take them. In these cases, treat withdrawal based on your patient’s symptoms (see table on page 6 for some commonly used agents). Overall, this strategy doesn’t work as well, but it’s something to consider—especially for patients intending to initiate long-acting injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol), which requires first being opioid free for 7 to 10 days.

Transitioning from detoxification to treatment

Encourage patients to begin outpatient opioid use disorder treatment after detox, and ensure they have a reliable follow-up plan. If your ED has access to a recovery coach in house, arrange a meeting before discharge. If your patient declines a referral, stress that their risk for relapse and overdose will be high. Those who decline further treatment should have their medications tapered off prior to discharge. In contrast, patients who agree to treatment can have their dose gradually increased up to standard outpatient dosages (30–40 mg for methadone and 8–24 mg for bup/nx). For bup/nx, provide a prescription for a week or so, if possible, to cover them until they can see a certified outpatient provider. Supply a naloxone prescription or kit before they leave the ED, too.

Basic harm reduction strategies

Before your patients leave your care, don’t forget to mention harm reduction strategies. An ED visit allows you to review the following with your patients, especially if they receive the majority of their care emergently or decline follow-up treatment:

- Make sure patients know about local substance use treatment resources such as bup/nx providers and methadone clinics.

- Educate patients who use intravenously about bloodborne illness, the risks of needle sharing, and clean needle exchange programs.

- Order labs to check for pregnancy, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis. Offer vaccinations for hepatitis A and B, tetanus, and pneumonia (Visconti AJ et al, Am Fam Physician 2019;99(2):109–116).

- If available, offer access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (commonly called PrEP): antiviral medications shown to reduce HIV spread from engaging in risky sexual behaviors or high-risk injection drug use (Owens DK et al, JAMA 2019;321(22):2203–2213).

- Discuss risks of opioid overdose. Provide education about naloxone and a prescription for it.

CATR Verdict: The ED is a primary point of medical contact for individuals with unhealthy opioid use. Treat their withdrawal, preferably with bup/nx or methadone, and refer to treatment if willing. Don’t forget to exercise harm reduction practices such as offering appropriate infection screening, vaccines, PrEP, and a naloxone prescription. Finally, provide a list of community substance use resources and make a warm handoff if you can.

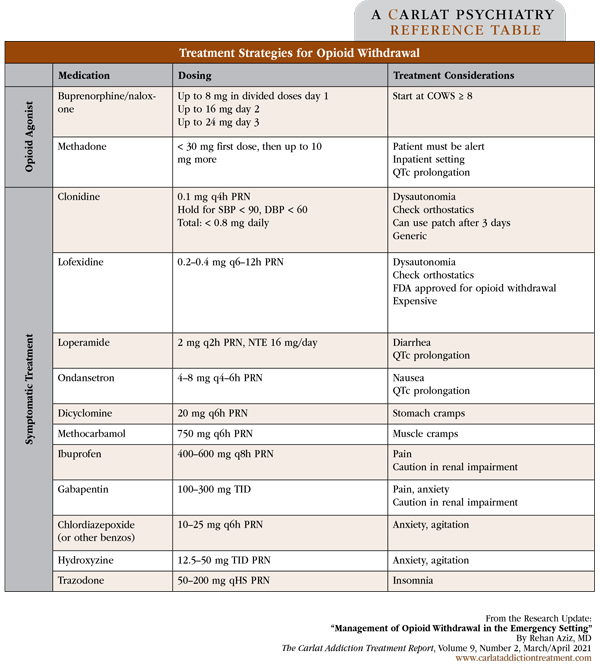

Table: Treatment Strategies for Opioid Withdrawal

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Issue Date: March 19, 2021

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)