Cannabis Use for Managing Agitation in Dementia

Cannabis, dementia, agitation, geriatric, therapy, old age, senior patient and psychiatrist, psychotherapy session

| Ground Picture/ShutterstockCGPR: What sparked your interest in cannabis use among older adults (OAs)?

Dr. Greenstein: After Massachusetts legalized recreational cannabis, I noticed more older veteran patients using it. Unsure how to advise them, my colleague and I researched its effects on OAs, including side effects, risks, and reasons for use. This topic became personal when my grandmother suffered severe agitation related to her memories of Auschwitz trauma during her end-stage dementia. Geriatric psychiatrists were hard to come by, so I stepped in, working with her PCP. Traditional medications, from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to atypical antipsychotics, were ineffective. Desperate for an alternative that wouldn’t oversedate her, I considered cannabis. I was inspired by the promising results I witnessed during my fellowship (Woodward MR et al, Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22(4):415–419). Patients who were unresponsive to conventional treatments for agitation in dementia benefitted from dronabinol, a synthetic cannabinoid. Consequently, my family tried a dissolving sublingual cannabis product from a dispensary (due to my grandmother’s trouble swallowing). It worked wonders, easing her agitation, helping her sleep, and allowing her to spend her final weeks without distress.

CGPR: Could you give us an overview of your discoveries and their implications?

Dr. Greenstein: Many OAs who use cannabis report they are using it for medicinal purposes rather than recreationally. Common ailments that cannabis is used for include chronic pain, insomnia, and some psychiatric conditions. Studies indicate that OAs report generalized improvements in their well-being from cannabis products (Yang KH et al, J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(1):91–97). This explains its appeal among the elderly for “therapeutic” use. It’s worth noting, however, that the term “medicinal” is somewhat fluid since medical cannabis does not have FDA approval for any indications.

CGPR: What’s the difference between CBD and THC?

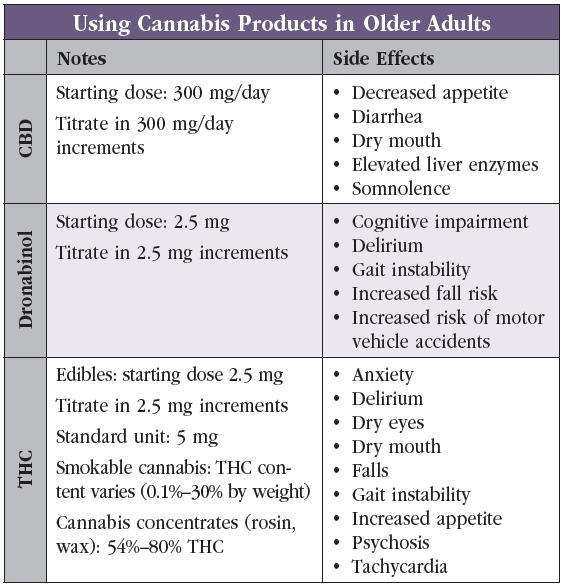

Dr. Greenstein: CBD and THC are both extracts of cannabis plants and are the two best-known cannabinoids. There are hundreds of others, and we don’t know much about them. Marijuana is the colloquial term for cannabis plants that produce the psychoactive compound THC, while hemp is the term for cannabis plants that primarily produce the non-psychoactive CBD. Hemp is not regulated under the same strict DEA policies as marijuana, and this is why CBD, a hemp product, is readily available across the country. Common side effects of CBD include decreased appetite, dry mouth, diarrhea, and somnolence, whereas side effects of THC include increased appetite, tachycardia, dry mouth, and dry eyes. THC can also cause anxiety and psychosis (Editor’s note: See “Using Cannabis Products in Older Adults” table).

CGPR: Are there strains that work better in OAs? How do you choose?

Dr. Greenstein: Unfortunately, studies have shown that strain names and even indica/sativa/hybrid designations are not clinically useful because they are not standardized (Smith CJ et al, PLoS One 2022;17(5):e0267498). The plants themselves are generally understood to be hybridized to the point that they aren’t all that different. While most effects of cannabis are attributed to THC and CBD, the extraction process often results in the co-extraction of other cannabinoids. For instance, cannabinol (CBN), another cannabinoid, is frequently added to cannabis products marketed for sleep and is being studied as a treatment for insomnia. Anecdotally, multiple patients previously dependent on zolpidem for sleep have transitioned to using cannabis products containing CBN, THC, and CBD. They report significant improvements in sleep initiation and maintenance, as well as fewer cognitive effects. I reserve dronabinol prescriptions for patients who are resistant to standard treatments, cannot tolerate them, refuse pharmaceuticals in favor of “natural” products, or have family members who are concerned about the black box warning on antipsychotics. In my experience, products from dispensaries that contain a range of cannabinoids are noticeably more effective in managing dementia-related agitation than dronabinol, which contains only THC.

CGPR: When treating agitation in dementia, when would you consider a dronabinol trial for your patients?

Dr. Greenstein: My initial approach is standard of care, which includes behavioral interventions and pharmaceuticals. If they aren’t effective or tolerated, I consider cannabis products. The literature behind dronabinol use in this population is not robust, so it’s not first line. I think of it in patients who don’t improve after the classic algorithm of starting an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, augmenting with an SSRI or serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, augmenting or switching to an atypical antipsychotic, and perhaps divalproex sodium (Depakote). I also consider dronabinol in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia with severe agitation or hallucinations. The number of therapeutic options for these patients is limited because of adverse reactions to dopamine receptor inhibitors. I might first consider quetiapine, which is marginally effective for most people, followed by pimavanserin, and then clozapine. Small-scale studies of dronabinol haven’t shown great effect in patients with synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies, although I’ve seen it work well in some cases. At present, it tends to be a treatment of last resort (Schimrigk S et al, Eur Neurol 2017;78(5–6):320–329).

CGPR: When discussing dronabinol with a patient and their family, how do you approach informed consent?

Dr. Greenstein: I approach it the same way I do for all medications, especially those that are prescribed for off-label indications. I educate the patient and family about the risks, possible benefits, and alternative treatments. I try to balance thorough informed consent and shared decision making with evidence-based recommendations. Although 10 states have dementia-related agitation as a qualifying condition for medical marijuana, my state is not one of them. Although I do not prescribe dispensary-sourced cannabis products, I still offer consultation on their potential risks and benefits.

CGPR: How receptive have your patients been to accepting dronabinol in treatment?

Dr. Greenstein: In Colorado, being ahead of the curve with legalization of cannabis products has shaped a general acceptance of its medical use. Patients or family members will often initiate the conversation about cannabis products for managing dementia-related agitation or other psychiatric illnesses. During informed consent, we must be upfront about black box warning on antipsychotics and the evidence around psychotropic use in OAs. This conversation sometimes leads patients or families toward wanting to try dronabinol first, as it does not garner as much fear. Like antipsychotics, cannabinoids aren’t universally effective and we don’t yet have definitive data on which specific subsets of patients they benefit. The same uncertainty applies to many pharmaceuticals—we won’t know their efficacy until we administer them. My overall strategy for dronabinol is the same as for any other medication I prescribe: Monitor patients closely, maintain open communication, and don’t be beholden to a medication if it is ineffective or not tolerated.

CGPR: Which risks do you highlight?

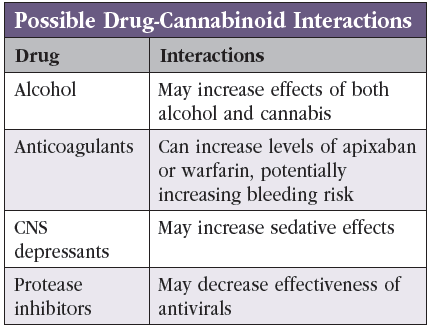

Dr. Greenstein: In terms of the safety profile of dronabinol and other cannabis products, there are studies that show they increase the risk of falls, motor vehicle accidents, delirium, and cognitive impairment (Solomon HV et al, Harv Rev Psychiatry 2021;29(3):225–233). Those are the main categories that we talk about when obtaining informed consent. In some patients we worry about drug-drug interactions (Editor’s note: See “Possible Drug-Cannabinoid Interactions” table). The main ones are blood thinners: warfarin, apixaban, etc. Cannabinoids can increase the serum levels of these drugs. You don’t want to cause somebody to be at higher risk for bleeding as a result of using these compounds. Based on the literature on CBD, it seems that the dose needed to increase the serum level is hundreds of milligrams at a time, as CBD has lower bioavailability (Millar SA et al, Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020;13(9):219). Still, I’m cautious. We don’t have guidelines on this, and I therefore stay very conservative.

CGPR: How do you discuss dosing cannabis products with patients?

Dr. Greenstein: In patients choosing to use cannabis from a dispensary, we review approximate amounts of THC—for example, smoking contains variable THC, whereas doses in edibles are standardized but more potent. Dronabinol, which is pure THC, is available in capsules with the smallest dosage being 2.5 mg. I start low, go slow, and titrate until there is benefit or poor tolerance. For instance, one patient with Korsakoff dementia responded well to 2.5 mg BID of dronabinol, which made her much less agitated and more directable, enhanced her participation in care, and helped her sleep well at night. I did not titrate the dose any further. I often warn OAs that cannabis products can hang around for longer in their systems than in younger adults. These products are fat soluble—and with increasing age, people have more body fat relative to water. Additionally, I mention that gummies or tinctures can take up to two hours to reach their full effect—so I suggest waiting between doses to minimize accumulation and risk for overdose.

CGPR: Can you share any other notable outcomes you’ve observed with cannabis use?

CGPR: Can you share any other notable outcomes you’ve observed with cannabis use?

Dr. Greenstein: I’m working on a challenging case of a woman in her 60s with early-onset Alzheimer’s (imaging and clinical presentation not consistent with frontotemporal dementia). She displayed extremely violent tendencies, leading to multiple evictions and elopements from memory care facilities. Initially, she was managed at home with 24-hour care. Securing inpatient psychiatric care was difficult due to reluctance by facilities in Colorado to involuntarily admit patients diagnosed with dementia with behavioral disturbances. Her agitation was not responsive to behavioral interventions. I trialed various atypical antipsychotics, divalproex sodium, and benzodiazepines, but none were able to reduce her scores on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) or eliminate her need for 1:1 24/7 care. With her court-appointed guardian’s consent, we offered her a cannabis product containing THC and CBD. She titrated up the dose of THC to 20 mg, at which point she became calm. The cannabis product produced this effect for four to six hours. Currently she’s on 60 mg of THC daily, dosed 20 mg TID. She has shown immense improvement, living in an assisted living facility, and no longer requiring 24/7 1:1 supervision.

CGPR: That’s a fascinating case. Are there specific scenarios or medical conditions that make you hesitate to prescribe cannabis?

Dr. Greenstein: Exercise caution with patients who have severe gait instability, history of negative reactions to marijuana or other substances, and severe psychosis due to the potential correlation between cannabis and psychotic disorders. Patients on blood thinners or who are still driving also prompt me to reconsider.

CGPR: Have you recommended CBD instead of THC for specific conditions, considering its milder psychoactive properties?

Dr. Greenstein: I haven’t yet. While CBD has lower oral bioavailability, studies are exploring its use for dementia and agitation. As with any psychotropic medication, individuals may respond differently to CBD, mixed cannabinoids, or THC.

CGPR: Given your experience with cannabis products, how do you track patient outcomes?

Dr. Greenstein: I rely on standard agitation scales, such as the NPI-Q or the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale. I also use the Caregiver Strain Index when appropriate to gauge patient well-being based on caregiver distress.

CGPR: How do legal aspects of prescribing cannabis vary? What precautions should be taken when patients can’t provide informed consent?

Dr. Greenstein: Legal aspects are complex and vary by state. In Colorado, for instance, individuals (and their guardians) can consent to cannabis use. If prescribing to those who can’t fully consent, consult an attorney regarding liability. There are associated risks, and we should be prepared for adverse reactions. I clarify to all my patients that any cannabis product they use is obtained independently, as I do not prescribe cannabis or certify a medical cannabis license for dementia-related agitation. I do, however, provide guidance to patients and families who are considering cannabis after standard treatments have failed or were poorly tolerated. Cannabis is far from a panacea, but it appears to have clinical benefits that we are just starting to define.

CGPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Greenstein.

Aaron Greenstein, MD.

Aaron Greenstein, MD.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)